“The chief obstacle to a woman’s success is that she can never have a wife.”

Anna Lea Merritt (19th Century Artist), Lipincott’s Magazine.

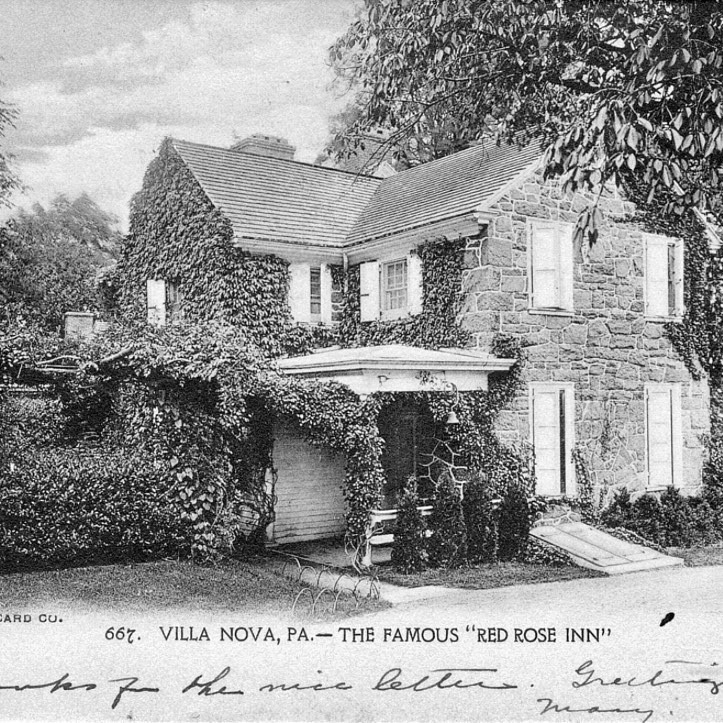

Virginia Woolf may have nailed the formula to becoming an independent, creative woman in her 1929 essay A Room of One’s Own, but groups of artistic women had been testing this formula for decades, forsaking familial duty, and setting up, not just rooms, but independent homes of their own. One such group was known as ‘The Red Rose Girls’; a set of prolific and successful artists from Pennsylvania who made a pact to live together forever and share a highly unconventional lifestyle at the turn of the Twentieth Century. While renting out the Red Rose Inn in Philadelphia, they lived on their own terms exploring the benefits a communal all-female household. And at a time when women were barely even permitted to attend art school, they enriched each others careers and thrived together as self-sufficient artists.

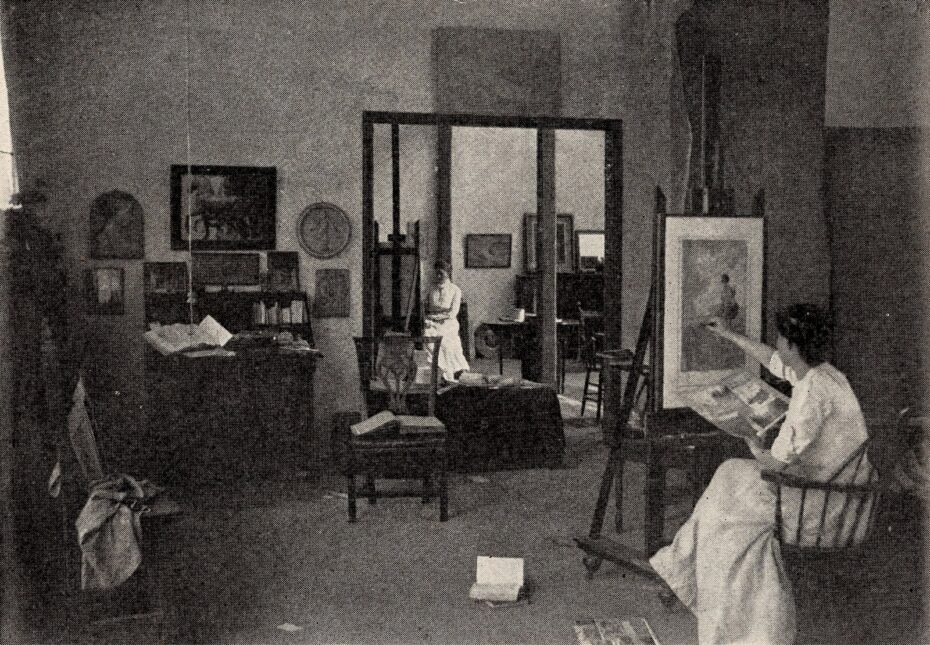

The three artists were Violet Oakley (1874-1961), Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935) and Elizabeth Shippen Green (1871-1954) who were joined in their home by a fourth member of the group, Henrietta Cozens, a horticulturalist who was the only non-artist in the group. It was their friend and mentor, Howard Pyle, who taught all three women in his illustration class at the Drexel Institute, and who also coined their famous nickname, “Red Rose Girls” and encouraged them to shun marriage in favour of a communal arrangement that fostered mutual support and inspiration. When they were short of a model, they dressed in costume and painted each other. Together, they pioneered the artistic style of Romantic Realism, and while they helped put Philadelphia on the map as a national centre for book and magazine illustration, the women’s radical choice to live together certainly raised more than a few eyebrows in the 1910s.

‘Baching it’, as the custom of sharing an apartment became known, may have been frowned upon by society but within the very small world of women artists, it was becoming a popular alternative. It was a way to save money and to “create […] a family, not to have children but as a support base from which to pursue their careers.” (Charlotte Herzog, Woman’s Art Journal, A/W 1993-4).

Howard Pyle certainly didn’t mince his words, forthrightly pronouncing that once a woman married, that was “the end of her” professionally. Pyle’s views on marriage for women artists was supported by another 19th century artist, Anna Lee Merritt, who wrote in Lipincott’s Magazine, that without a wife, “it is exceedingly difficult to be an artist without this time-saving help.” The Red Rose Girls overcame this obstacle in the form of their fourth member Henrietta Cozens, who Alice Carter, author of The Red Rose Girls: An Uncommon Story of Art and Love, describes as ‘the wife’. She was gardener, cook and household manager. Hers may seem the least desirable of the group’s roles, but it was one highly regarded by the three artists and she was a loved, valued and considered an indispensable member of their small community. When the tenancy on the Red Rose Inn expired in 1906, the four women moved together to a new home they called “Cogslea” after the acronym COGS, formed by their initials and began referring to their group affectionately as the ‘Cogs Family’.

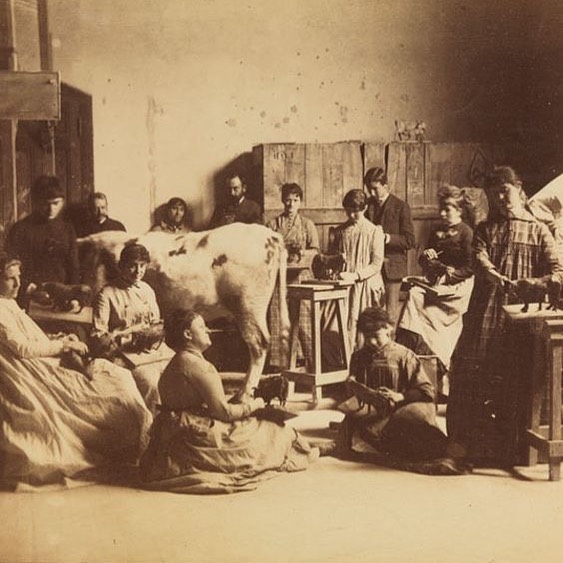

For the modern woman, it is difficult to appreciate just how difficult it was for The Red Rose Girls and their contemporaries to not only work as artists, but to even be allowed the opportunity to study art professionally at all. A woman may be encouraged to ‘dabble’ in painting as part of her fashionable education but was expected to then choose marriage, never a career. Choosing both would surely result in chaos. A female artist was on the edges of society, her reputation questionable and her marriage prospects in tatters. Society’s greatest fear? “A woman in a life-drawing class might have her passions inflamed by seeing the nude model […] leaving her unfit for her best career which was marriage,” curator Alice Carter astutely reminds us in an interview on NPR.

In her wonderful article A House of Their Own: The Red Rose Girls, Anne Wallentine describes how the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art (PAFA), where Oakley, Willcox Smith and Shippen Green all studied at various times, was a rare exception to most art schools, allowing women to participate in gender-segregated life drawing classes during which “male models remained partly draped for “modesty”. When one of their teachers (and a strong supporter of women artists), Thomas Eakens removed the loin cloth of a male model to a class of female students, he was fired.

Inevitably, as with so many all-male or female relationships throughout history, tongues have waggled in an attempt to work out the nature of their friendships. Were The Red Rose Girls more than just friends and, more importantly, does it matter? They certainly shared an intense bond, but many Victorian women expressed affection in ebullient, hyperbolic language. Tellingly, such ‘romantic friendships’ were not deemed threatening in the way that homosexual relationships were, the implication being that cohabiting women were celibate, lacking in physical desire, which could only manifest when in the presence of a man. However, The Red Rose Girls were labelled ‘unconventional’, what Wallentine calls “that curtain-drawing, nose-tapping word for ambiguous relationships – and for women who deviated from any of society’s expectations.”

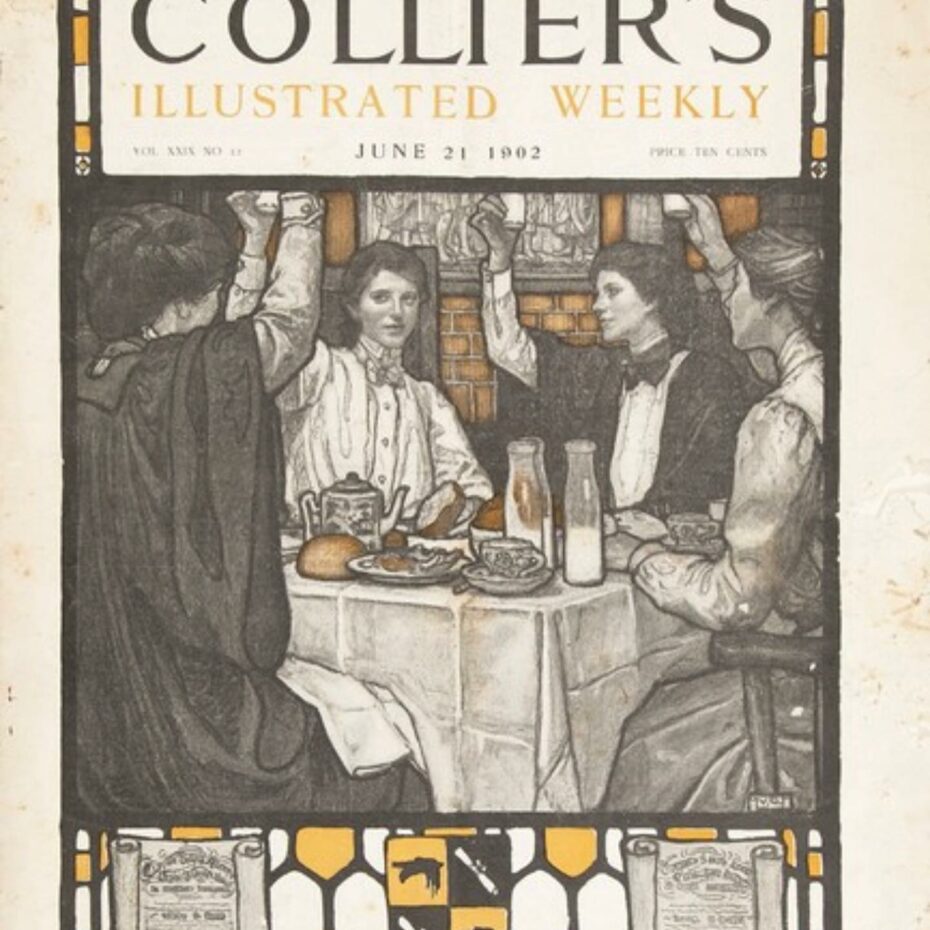

Contrary to the harmful stereotypes of “hard-hitting” feminists, an examination of their art exposes a soft, romantic sentiment and celebration of all things feminine. Jessie Willcox Smith, one of the most popular book and magazine illustrators of the Twentieth Century painted delicate pictures depicting idealised children, although, she never had any children of her own. She illustrated over forty popular children’s books including The Water Babies, Little Women and Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses as well as designing the cover illustrations for Good Housekeeping magazine for fifteen years – hardly the most radical of publications, but these were the mediums in which her work was allowed to thrive.

Elizabeth Shippen Green was commissioned by Harper’s monthly magazine for which she designed hundreds of covers and interiors, and is best known for illustrating Mabel Humphrey’s bestselling The Book of the Child (1903).

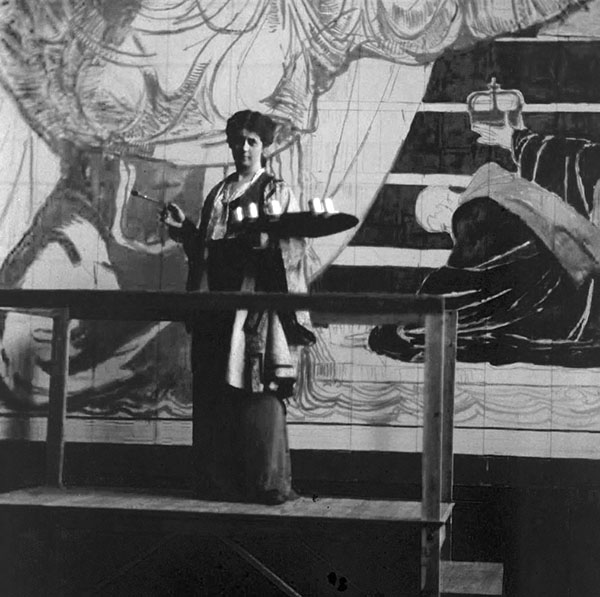

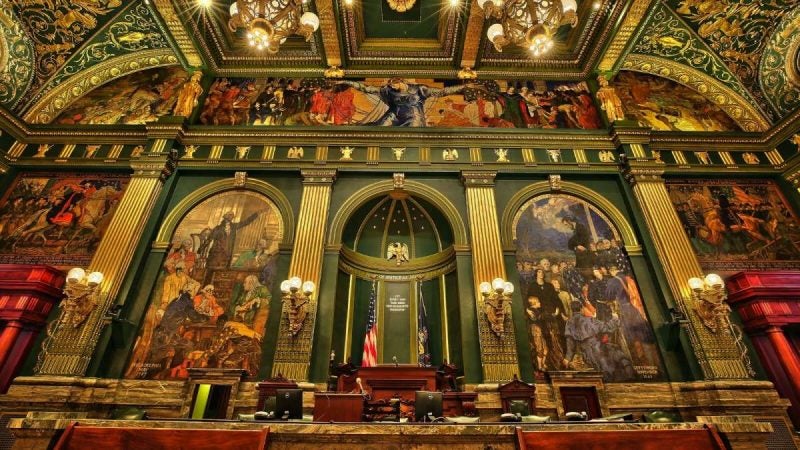

Violet Oakley, on the other hand, was famous for a set of enormous murals (forty feet long), completed between 1902 and 1906, in the Governor’s reception room at the Pennsylvania State Capitol Building, for which she was awarded a gold medal by the PAFA in 1905. For a woman to be chosen to decorate such a male-dominated space was unique in itself, as was her becoming one of the first women to teach at the PAFA in 1913.

The Red Rose Girls continued to cohabit until 1911, when Elizabeth Shippen Green married Hugo Elliot after a five year engagement, a ‘tragic twist’ to the tale that Alice Carter believes “the tightly intertwined group never fully recovered”. The Philadelphia Press’ report rang more like a eulogy than a celebratory announcement: “a note of sadness was felt when the realization came that the trio of artists who had lived and worked together for so long would be depleted by the absence of Mrs Elliot.” Violet Oakley made creative use of the vacant space left by Shippen, taking over Cogslea while Jessie Willcox Smith and Henrietta Cozens moved to Cogshill, another fondly named property on their estate, living together until Smith’s death.

In an essay for the Encyclopaedia of Greater Philadelphia, Mark W Sullivan describes the achievements of The Red Rose Girls as going “far beyond the confines of the Philadelphia region. As pioneers of expanded options for women in the early twentieth century, they exerted a wide influence on American art and society.”

Their living arrangement and relationships gave them the space and independence they needed to become the lucrative and prolific artists they undeniably were. They certainly inspired one other (and generations of women to follow), spurring each of them on to greater productivity and creativity.

Photographs of the group also clearly reveal a sense of humour. A few cheeky, knowing looks hint at the kind of fun and mischief this Victorian girl gang enjoyed behind-the-scenes in their “no boys allowed” clubhouse. Generations later, we live in a ‘modern’ society where women who never marry still face a social stigma. We continue to subscribe to a media culture in which a woman’s value is still so heavily weighted in how she looks, fuelling insecurities and competition that disconnects women from each other in many ways. Stories of strong female friendships and female camaraderie like this deserve a much larger space in the mainstream narrative. And truthfully, who wouldn’t secretly wish they were the fifth group member of The Red Rose Girls?