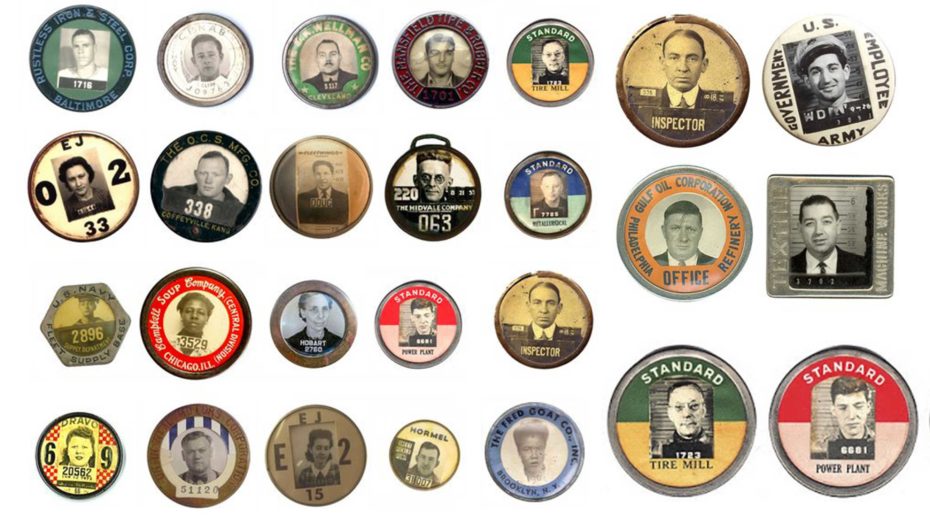

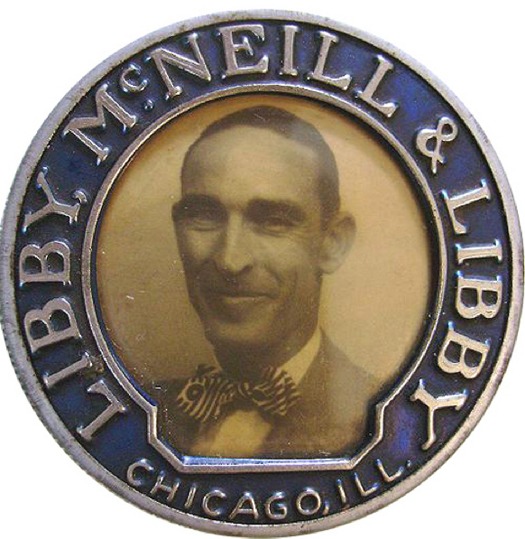

From the 1930s to the 1950s, these charming little I.D. badges were rolled out across America as a “fail-safe” homeland security measure in a crackdown on the threat of industrial espionage. Each badge gives clues to a story, whether you’re trying to piece together the identity of the person or the company they worked for. Just by looking at that black & white mugshot, you can discern from a bow tie or even from a certain expression on their face whether the individual had a position of rank or worked on the factory floor; if they were content with their job or perhaps felt undervalued. And then there’s the design of the badge that contains the photograph. Those delicious vintage fonts, both on the metal frame and within the ID badge. A little detective work is required to determine whether the company still exists or if it went bust decades ago. What the badge doesn’t tell you can only feed the imagination.

Were they effective? Something tells me these badges would have made an easy weekend DIY project for any wartime spy. The threat however, was very real. In 1942, eight Germans plotted to stage sabotage attacks on American economic targets; companies just like these. Under “Operation Pastorius”, the spies successfully arrived in two German U-Boats, one in New York, one in Florida. Emerging in full German uniform, they buried their explosives, primers, incendiaries and uniform on the beaches before putting on civilian clothing and boarding trains inland. The plot was foiled when one of the spies George John Dasch (who had previously lived in America and even served in the U.S. Army Air Corps) walked into the FBI headquarters and dumped the entire budget of $84,000 on the desk of an agent, demanding to speak with Director Hoover. All eight Germans were tried and convicted of treason and espionage and sentenced to death. Dasch and one other German agent who had almost immediately lost his nerve and betrayed his comrades upon arrival on US soil, had their sentences reduced to prison time. Then FBI Chief J. Edgar Hoover made no public mention of Dasch turning himself in, and took credit (as he was often known to do) for cracking the spy ring.

But I digress. Are these badges worth anything as a collector’s item? Collectors and archivists of vernacular photography, Barbara Levine and Paige Ramey of PROJECT B say the badges “have become of great interest to collectors since they exemplify two important cultural traditions: the use of photographs as jewellery (mourning pins, rings and novelty pin-back buttons) and as an instrument of authority or identification (mug shots, passports and licenses)”. To give you an idea of their potential worth, a collection of 49 badges recently sold for 5000 euros on 1st Dibs.

“Dating from long before the era of digital security cards and fingerprint readers,” notes Project B, “photo badges are both a personal keepsake and an object of cultural history, looking to us now like wearable time capsules.”

I had a look on eBay and found that non-metal backed badges can run from about $40, while the more interesting metal ones can go for just over $100. I expect you might be able to find some of these (at collector-friendly prices) hiding in flea markets and estate sales.

I can picture these looking quite striking displayed in a collection as part of a curiosities wall, inside a frame or even added to a leather jacket. Make sure to keep a keen eye out for these little antique oddities on your next thrifting adventure. In the meantime, take a look at this archive curated by Mark Michaelson, author of the book Least Wanted: A Century of American Mugshots. Happy collecting!