We forget that once upon a time, social status had a lot to do with the common houseplant. We’re talking about the parlour palm, one of the most significant decorative features in a Victorian home, which referred to any number of varieties of palms, ferns, and other hardy perennials that were native to South America, Asia, and Africa. From the late 1850s, the essential home accessory became a symbol of wealth, status and intelligence. They had the power to say you were smart, sophisticated, worldly, and most importantly, rich! So naturally, the parlour palm – or even better, a small rainforest of parlour palms – would be prominently displayed in the front windows for all the neighbours to quietly envy. And who were you if your houseplants didn’t take up significant space in portraits and family photographs? Curiously, the ultimate flex of the Gilded Age was not gold, but green…

The story of how these tropical plants made their way into damp and cold estates in Britain begins with a British botanist named Dr. Nathanial Bagshaw Ward (1791-1868). Little is known of his early and private life, but Ward was an avid botanist though he was a physician by trade and practiced in the crowded, polluted East End of London for most of his life. His calling is said to have been sparked by a visit to Jamaica in his adolescence. After many failed attempts to raise and maintain a garden of ferns and mosses in the smoggy backyard of his London home, Ward began experimenting with the chrysalis of a sphinx moth by placing it in damp soil in a glass jar with a sealed lid. Following careful observations of the moth’s growth from chrysalis to pupa, Ward witnessed the condensation which kept humidity and temperature at a steady level within the jar.

“Thus, then, all the conditions requisite for the growth of my fern were apparently fulfilled, and it remained only to test the fact by experiment. I placed the bottle outside the window of my study, a room with a northern aspect, and to my great delight, the plants continued to thrive. They turned out to be L. Filix mas and the Poa annua. They required no attention of any kind, and there they remained for nearly four years, the grass once flowering, and the fern producing three or four fronds annually.”

Dr. Nathanial Bagshaw Ward

Ward went on to hire a carpenter to build him a case for another experiment, a case made of the hardest wood with a frame built as tightly as possible to resist condensation and decay, this was the first terrarium ever built. In July 1833, he began his experiment by shipping two of these custom cases filled with native British ferns and grasses to Sydney, Australia. The cases arrived in Australia after six months at sea and when opened at Sydney harbour, all the plants had survived and were thriving. Per his instructions, the cases were cleaned out and filled with native Australian plants that had previously failed to survive a long sea voyage. The cases did not arrive from the return voyage until February 1835 but after the long and delayed voyage, they arrived in London and Dr. Ward inspected their contents. His experiment was a success with all the native Australian plants alive and thriving within the cases.

The first person with whom Ward shared the news of his success was William Jackson Hooker, the first director of Kew Gardens at the time. And in 1841, a case built exactly as Dr. Ward had described in his letter successfully traveled back to Kew Gardens from an expedition of the Falkland Islands and Antarctica with native plants from the region. Following this success, Kew Gardens, botanical tradesmen, and merchants adopted the use of what became known as Wardian cases to ship previously impossible-to-ship exotic plants and fern species from their native countries to England and Europe.

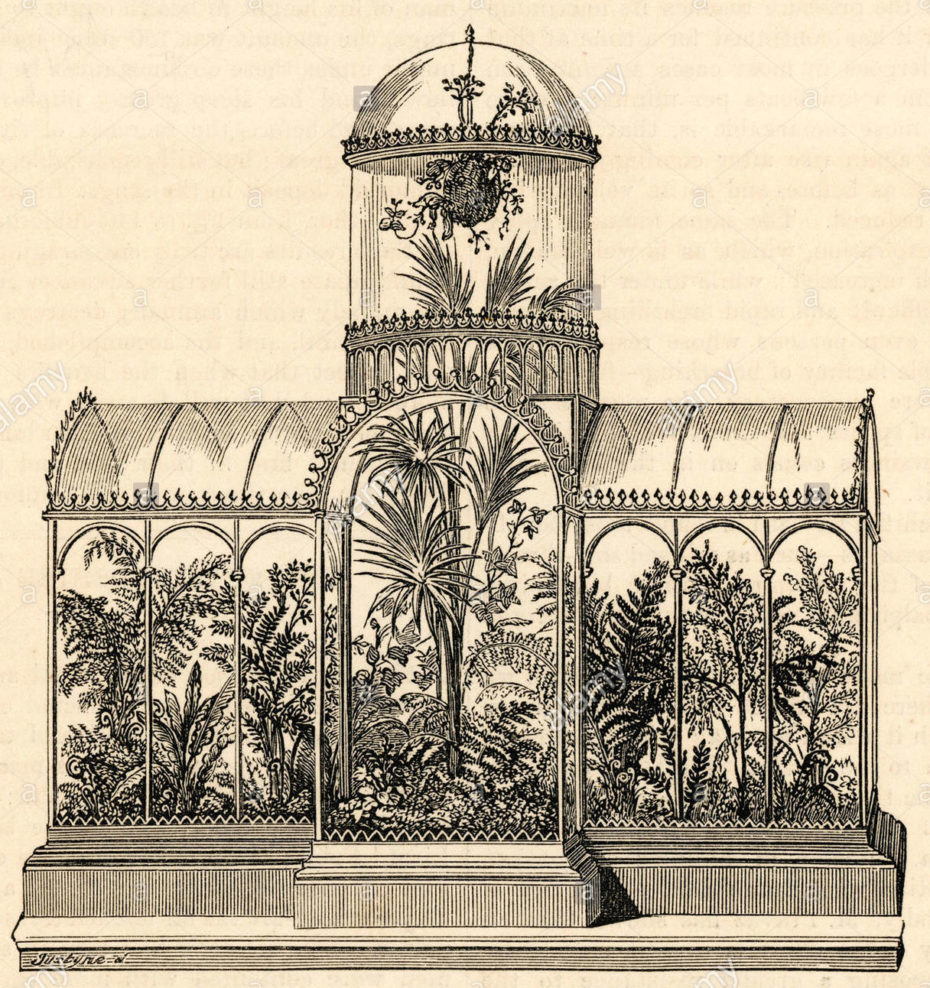

Wardian cases became a fixture in middle-class and upper-class homes in England where a passion for raising exotic plants, particularly ferns and orchids practically became the national sport. As Wardian cases became larger and more ornate, Dr. Ward’s cases made the great orchid craze of the late Victorian age possible.

Original antique examples of a Wardian case are extremely difficult to find in good condition, especially online, but we did find one company that makes them. The Wardian Case Company can make you a veritable miniature Crystal Palace.

In 1854, it was acknowledged that Dr. Ward’s discovery had changed the face of commerce worldwide, but prior to his discovery, few exotic plants were exported from tropical and warmer climes to cooler climes in the West, and even fewer survived the journey. Most middle and upper-class British homes displayed cut flowers grown locally or even from their own gardens and in the winter, when fresh flowers were scarce, bouquets of dried flowers were kept in their place until spring heralded the arrival of fresh flowers. Exotic plants were far from a standard in homes with the exception being royalty, who could afford to commission explorers or merchants to bring back selections of native flora and fauna (but no amount of money could keep the more sensitive and delicate species alive for the duration of the sea voyage).

With Wardian cases, exotic plants of many delicate varieties could be successfully transported and and some varieties would even thrive indoors without a case. Years passed and it was not only smaller plants like ferns, orchids, and grasses that were imported but larger plants like banana trees, palms, fruit trees, and vines that became attainable for use as home decor in Victorian homes where the term parlour palm was born.

Popular varieties of plants kept in low-light Victorian homes were Aspidistra from the lily family, a dark green leafy plant possessing the ability to survive in near total neglect with a great tolerance for dim Victorian chambers and estate rooms, another was the Chamaedora elegans, or the parlour palms, with its feathery foliage, it prefers limited light and is easy to care for. Other species include the Kentia palms (Howea forsteriana and H. Belmoreana), the Dwarf Date Palm, and the Ponytail Palm also called the Elephant’s Foot (Beaucarnea) because of its peculiar swollen stem which is a succulent related to the yucca.

As the preference for house plants spread, parlours, drawing rooms, and staterooms became filled with wide varieties of exotic plants. Plants not only became part of the decor, they were part of the entertainment. Botany was a popular subject to be debated amongst dinner party guests and those who knew most about it – the names of plants and their scientific qualities – were the toast of the room.

For much of history plant-keeping was primarily a man’s domain, but as we’ve previously explored on MNC, gardens and greenhouses became an enlightened woman’s secret haven of discovery, expression and temptation in the 18th century when a first wave of botanists were sexing up the study of plants, going as far as to juxtapose our own reproductive systems with plant anatomy, comparing the stamen to a man’s phallus, the style to a woman’s intimates, even the plant petals to a bed and the leaves to the bedroom curtains.

“While male authors were among the earliest proponents of potted plants for the interior, women in Victorian households were often responsible for tending to them,” notes Trent Rhodes for the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture. “They used plants not only to bring life to decorated rooms, but also as a means for displaying their knowledge.”

The house plant marked a great change in the Victorian era and well into our present day, a change that affected not only the décor of Victorian salons but commerce and botanical trade at the time. Plant commerce was now changing drastically and large botanic garden centres and plant museums profited greatly. This unchecked transport of plants lasted well into the 1950s until new laws for importing and exporting plants were instituted which slowed and changed the way exotic plants were brought into countries limiting the spread of pests, diseases, and invasive species, risks that had been previously unconsidered.

In the 1930s, houseplants (native or exotic) became attributed to the term ‘British colonial style’, along with furniture crafted from rattan or any other natural material like bamboo. This influence in décor and the invention of ‘British colonial style’ was born from the period of time when the British empire already stretched across the globe and controlled many countries in continental Asia and Africa, appropriating various cultures, styles, art and natural resources to fuel the British economy, as well as enriching British homes, museums, and even British “style” as we know it. ‘British colonial style’ doesn’t actually exist without those base elements appropriated from native countries within the British empire. As with most trends and fads, they became so synonymous with day-to-day life that we often forget their origins, or that prior to the trend’s onset, elements of it were difficult to obtain and that sudden shift came at a great price.

When he died in 1868, Dr. Ward’s personal fern herbarium contained around 25,000 specimens. He remained an avid botanist until his death. His legacy is perhaps best captured in our favourite period dramas, in which parlour plants make frequent appearances as part of the scenery. Howard’s End (1994) based on the novel by E. M. Forster is set in 1910 and features a lovely selection of indoor greenery.

Downton Abbey boasted several great rooms with a selection of parlour palms and other exotic plants. The Crawley family’s Downton Abbey estate is a stunning example of exotic indoor plant and parlour palm use in creating historically accurate sets for the turn-of-the-century England.

As the trend gained momentum, upper-class members of society branched out from just keeping pots of parlour palms and exotic plants in their homes but many built winter gardens, or glass conservatories, onto their homes where they housed large varieties of plants, as seen in the proposal scene of An Ideal Husband (1999) and the highly underrated British TV series Jeeves and Wooster starring Hugh Laurie and Stephen Fry. Throughout the tv series, there are a plethora of sets full of parlour palms and exotic plants taking us from the late 1920s into the 1930s at the series’ end.

Living in the post-pandemic work-from-home era that we do now, we are perhaps more appreciative of the beauty and atmosphere parlour palms and indoor plants can bring into a home, how they can transform a room and even our mood. We are investing in our home spaces more, dressing them as we wish to see them and bringing in elements that spark joy in our lives, even if it’s something as simple and attainable as house plant that you purchased from the shop around the corner. Just remember the Victorians are to thank for that.