Sphinxes, scarabs and obelisks, oh my! Egyptomania quite literally indicates a madness for anything Egyptian; a phenomenon most of us tend to associate with the 1920s when archeologists cracked open King Tut’s tomb and unleashed a new wave of excitement that penetrated every facet of mainstream western culture. But our fascination with ancient Egypt spans a much greater timeline; its influence enduring far and wide throughout every chapter of its subsequent history and physically manifesting time and again in our daily lives. So let’s take a journey through ancient Egypt … just not in Egypt!

The timeline of Egyptomania arguably goes thousands of years. The term comes from the Greek words Egypto (Egypt) and mania (madness or fury), which is entirely appropriate since the Greeks (along with their copycat friends, the Romans) kickstarted the first wave of an obsession with all things Egyptian. Greek historian Herodotus penned his Histories in the fifth century B.C.E., chronicling his travels and the curious tales he picked up while swanning up and down the Nile.

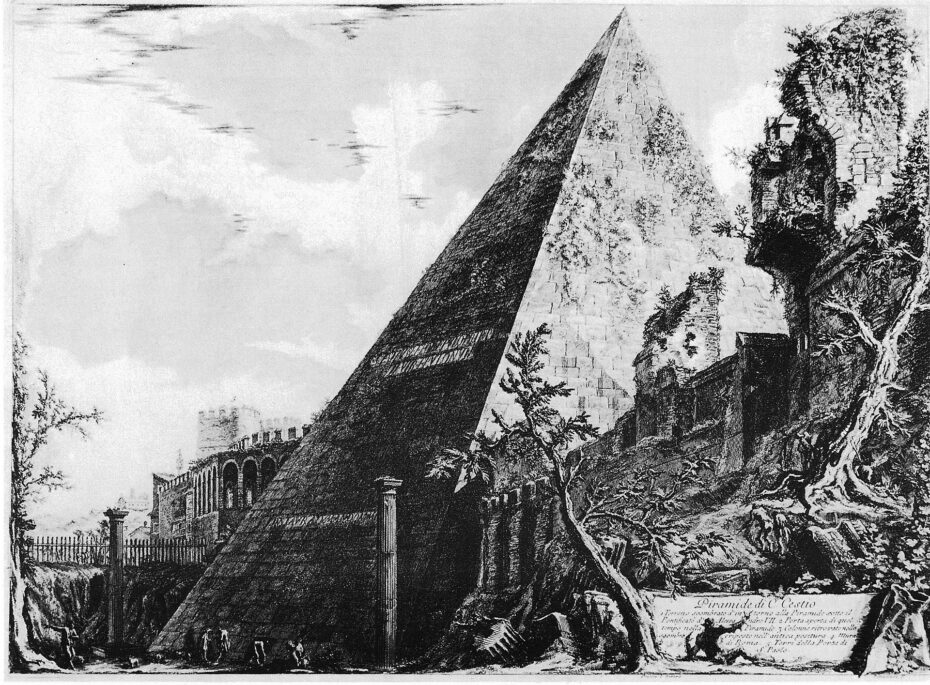

A few centuries later, in 31 B.C.E., following Emperor Augustus’s conquest of Egypt, Egyptomania also made its way to Rome and would endure. High official Caius Cestius erected a pyramid-shaped tomb in 130 AD (a trend that would make a comeback in Europe in the 18th century) and Emperor Hadrian venerated his dead lover Antinous as Osiris, the Egyptian god of the underworld. Cults from ancient Egypt spread across the Roman Empire, particularly those venerating Isis, where you can even find temples to the Egyptian goddess as north as modern-day Hungary.

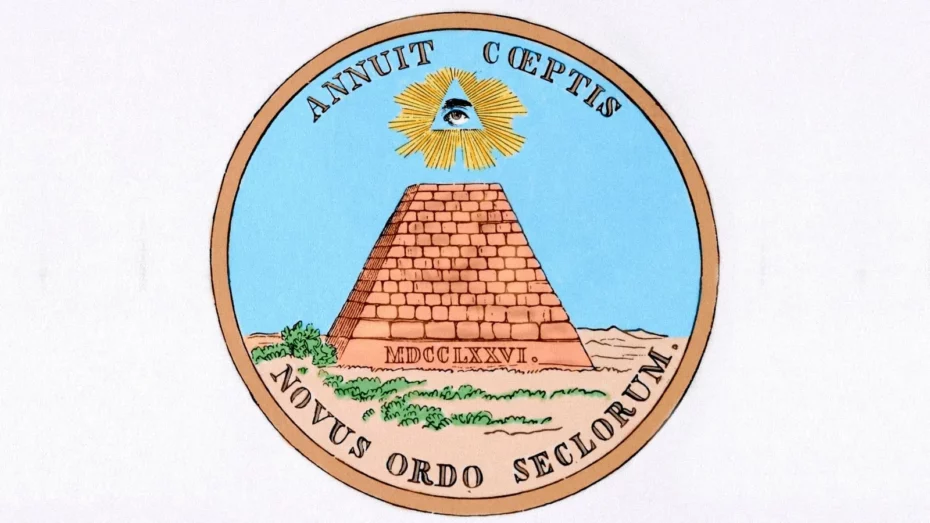

Egypt trickled into 18th century Europe via the Freemasons. We could think of Egyptian Revival Freemasonry as a prototype for modern Egyptomania as they hungrily consumed anything that contained hints of Egypt, like Abbé Jean Terrason’s Life of Sethos, Taken from Private Memoirs of the Ancient Egyptians written in 1731. Although Freemasonry mainly mixed elements of Christianity, Judaism, Kabbalah, and alchemy, it also drew aesthetic inspirations from ancient Egypt thanks to the Hermetica, a collection of books with roots in Egyptian magic written in the Greco-Roman period that influenced occult thinkers from mediaeval times to the age of Enlightenment. The Freemasons were highly secretive, but details of their mysterious rituals and symbols sometimes spilt into the real world. We saw their love for Egyptian esoterica and aesthetics influence art, like the Egyptian setting for Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Masonic opera, The Magic Flute. The Masonic interest in Egypt also stretched to architecture, like the Pyramid at Parc Monceau in Paris, built to the design of Phillippe d’Orleans, cousin to King Louis XVI and a Freemason.

Yet Egyptomania, as we know it today really began to kick off with the Napoleonic era, and much like the first wave of Egyptomania in ancient Rome, it all started with colonisation. During Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign against the Ottoman Empire at the turn of the 19th century in Egypt and Syria, his troops invaded Egypt and brought many scholars and scientists with them. Under this short-lived French occupation, which ended in the early 19th century, ancient Egyptian treasures were uncovered, excavated from the desert, and brought to western Europe, filling museums with looted Egyptian artefacts.

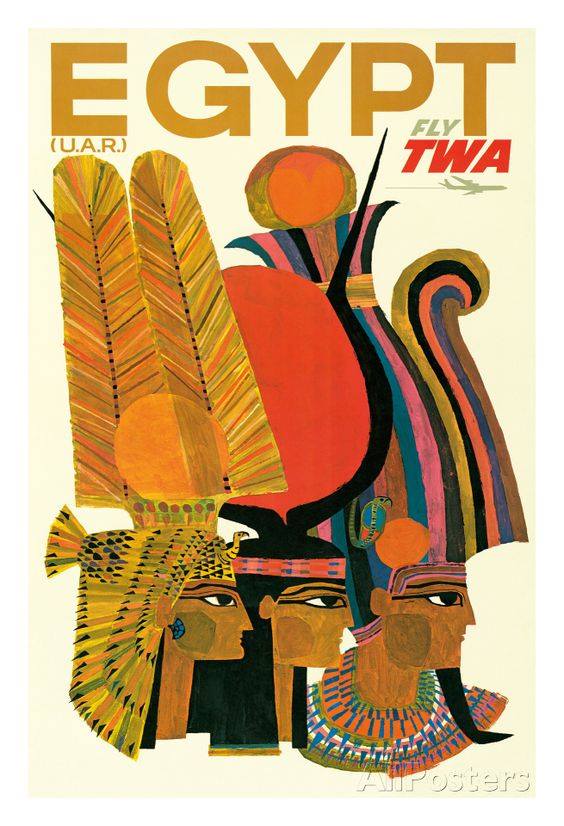

Following the discovery of the Rosetta stone in 1799 by French troops, Jean-Francois Champollion deciphered the hieroglyphs in 1822, unlocking Egypt’s once-hidden past. Monuments, tombs, and papyri could now be translated and a new understanding about the civilisation flooded into Europe’s intellectual landscape. Western writers, artists and thinkers travelled in droves to the “Land of the Nile”, sparking an innovation in design back on the continent. Ideas of the past were fresh, and Egypt was a destination people were hungry to explore.

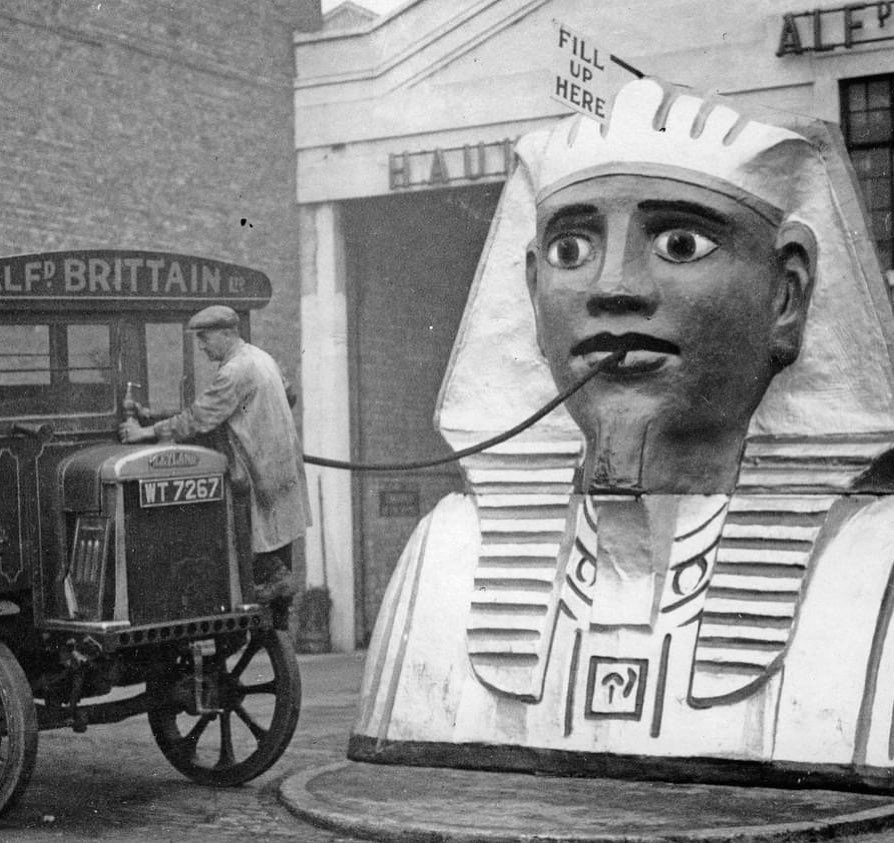

Before the age of mass tourism, only the elite actually had the means to travel, but if you couldn’t go to Egypt, then Egypt came to you. And it started with Egyptian-inspired architecture. Around the time of Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt, Paris opened one of its first covered shopping arcades (aka the world’s first shopping malls), the Passage du Caire (Cairo). Today it’s lost its grandeur but it was once outfitted with luscious depictions of the Egyptian goddess Hathor, papyrus columns, and carved figures and symbols.

Casting its shadow for the past 200 years over the city’s grand Place de la Concorde (occupying the former location of the French Revolution’s main guillotine), is one of a pair of seventy-five foot high ancient Egyptian obelisks that once stood on the left of Luxor Temple’s portal. The 3,000 year old structure had been coveted by France since Napoleon’s campaign was eventually transported there in the 1830s as a gift from the ruler of Ottoman Egypt at the time.

Both obelisks were originally gifted to France but after the first one cost the modern-day equivalent of $19 million to remove and transport, no attempt was ever made to bring over the second one. In return for the gift, France offered the Ottomans the Cairo Citadel Clock, but since its arrival in the 1840s, the mechanical clock has rarely worked. Further along the Seine, you’ll also find the Fountaine du Palmier, with four sphinxes spouting water below a column which was commissioned to commemorate Napoleon’s victories in Egypt.

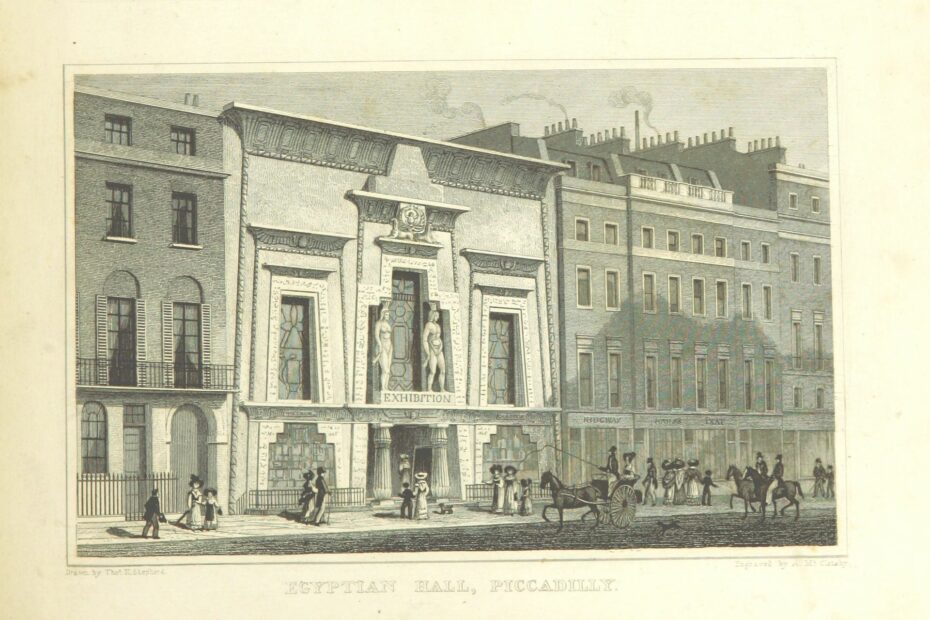

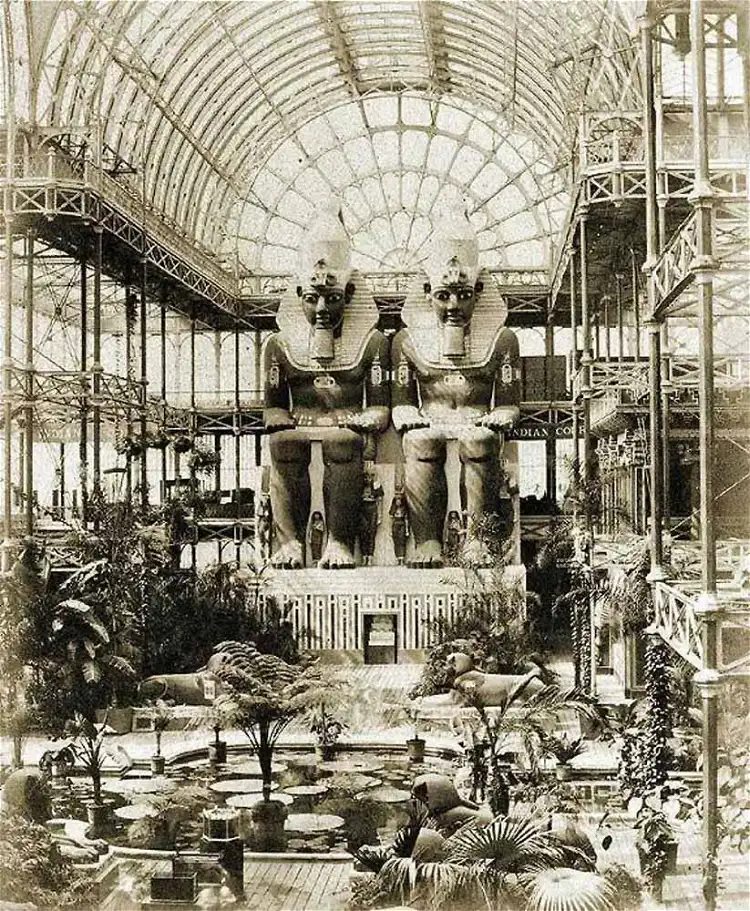

Across the channel, one of the more popular tourist attractions in 19th century London was an impressive faux-Egyptian temple in the heart of Piccadilly, sandwiched in between Regency townhouses. The Egyptian Hall was a museum featuring curiosities to fuel morbid Victorian obsessions of “Deformitomania”, including human exhibits and “freakshows”. It got the nickname “England’s Home of Mystery” after it gained an association with spiritualism and magic. It was demolished in 1905, but you can get a taste of the original at the Egyptian house in Penzance, dating back to 1835. Once a geological museum and shop, it’s now a holiday home, so you can even book a night here or just come to gaze at the striking facade.

Egypt’s funerary art fascinated Europeans. London’s Highgate Cemetery was built in the 1830s, complete with a stunning Egyptian Avenue with Lotus columns and vaults topped with cavetto cornices typically found above the doors of ancient Egyptian buildings.

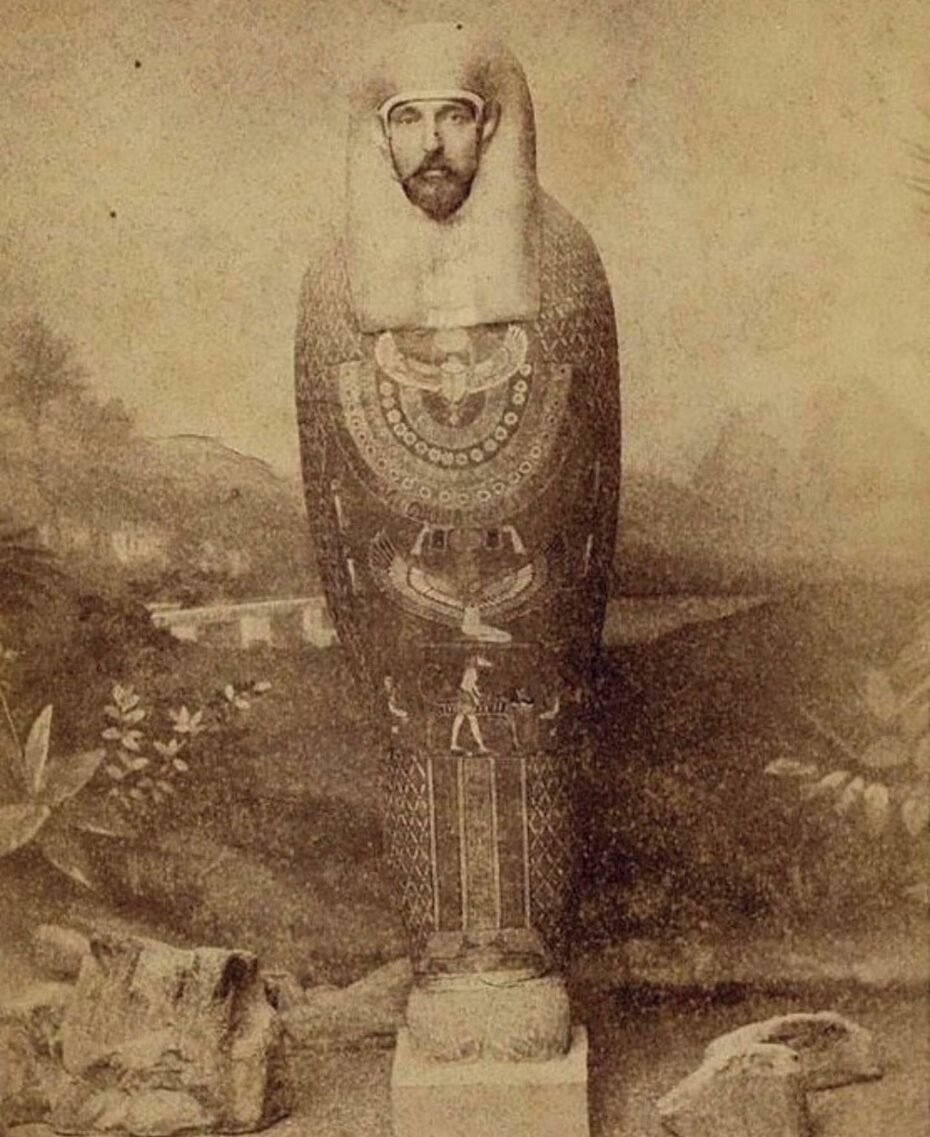

The fascination for Egypt’s funerary culture didn’t end with the architecture however. Mummies were used as a form of medicine. The trade of mummies took off in the 19th century, where tombs were sacked, and broken pieces of mummy could be bought for medicinal purposes. Early archeologists found that Egyptian mummies produced a semi-solid form of petroleum called bitumen that’s used in asphalt, thought to contain healing medical properties (dabs of it were applied in ancient burial rituals to the mummies’ cloths). The discovery gave the birth of the newest capitalist craze for those on the continent: breaking off a piece of that sweet, sticky bitumen and taking it to the bank…

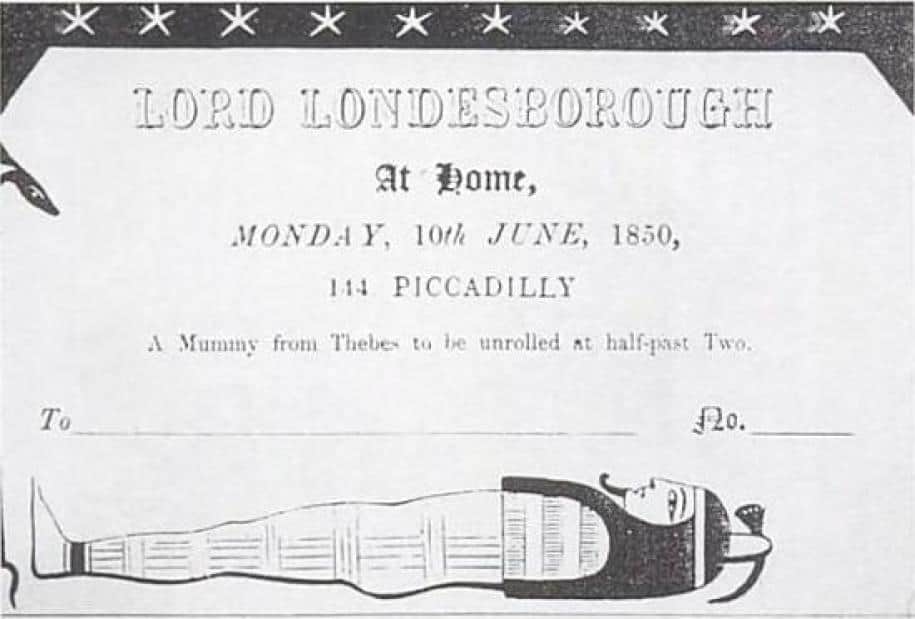

If you were to go to Egypt today, you might come home with a keyring or a fridge magnet, but back in the 19th century, bringing home a mummy was the must-have souvenir du jour. You could get a mummified head, hand, arm, or foot, but those who could afford it preferred to take a whole corpse home. Mummy unwrapping parties even became a hot trend, which is precisely what they sound like: A bunch of Victorians throwing a party, where unwrapping an Egyptian mummy was the night’s highlight.

This relentless popularity of mummies is likely what led to their use in paint formulas. Pre-Raphaelite artists such as Martin Drolling and Sir Edward Burne-Jones were notable pioneers of painting with Mummy Brown (more about that here).

Egyptomania gained momentum in Britain, especially following the occupation of Egypt by the British from 1882 until 1956. Under British rule, more British academics and archaeologists worked in Egypt, uncovering new tombs, temples, and treasures.

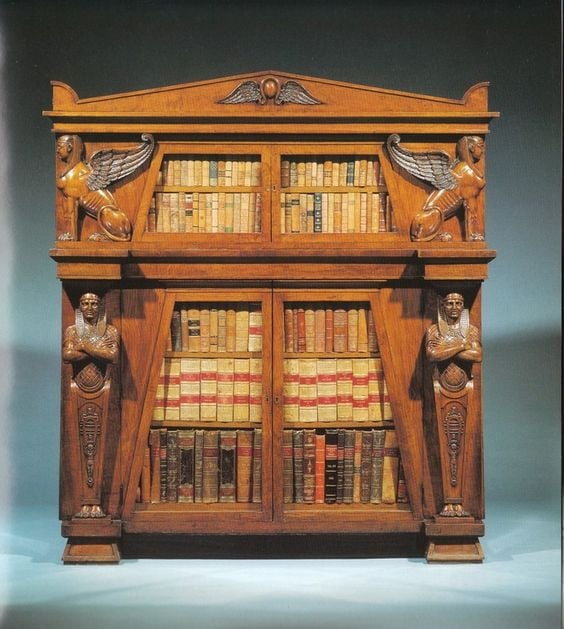

Ironically, the more awareness Victorians had of Egypt’s dynasties, the more they began to question the future of their own Empire. Imperial decline was an existential worry in Britain towards the end of the 19th century. Egyptian history served as an uncomfortable mirror– perhaps even a warning for the future –making Egyptomania more than just an aesthetic phenomenon in Britain, but reflected the concerns of the Victorians. Yet, despite the morbid fascination for its mummies, occult legends, and worries for a slowly dying empire, Egyptomania most notably left its most significant mark on fashion and interior decor. However, these were only a prototype for what would come in the 1920s.

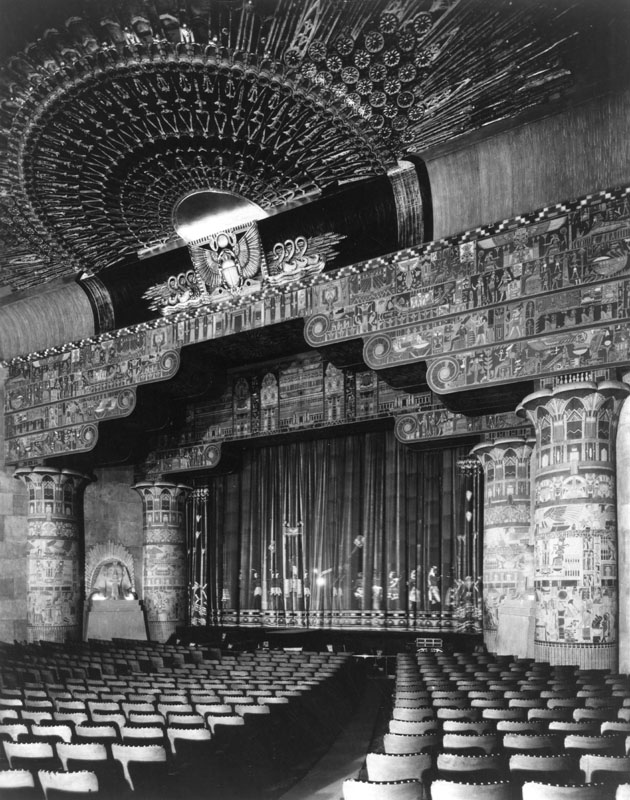

In 1922, Egyptologist Howard Carter led an excavation that would become one of the most significant archaeological discoveries in history: Tutankhamun’s tomb. The tomb dripping with jewels and gold, packed with furniture, board games, and other quotidian items from Pharaonic life, set off what many called “Tutmania.” Egyptomania moved up to another level worldwide, primarily through the fashion of the 1920s, but also permeated into literature and cinema, as well as ushering in even more Egyptian revival architecture with Art Deco styles drawing inspiration from geometric shapes and motifs found in Tutankhamun’s burial chambers. Art Deco also heavily featured Egypt-inspired icons like palm trees, scarab beetles, and cats, along with liberal lashings of gold and luxury that wouldn’t seem out of place inside an Egyptian pharaoh’s tomb.

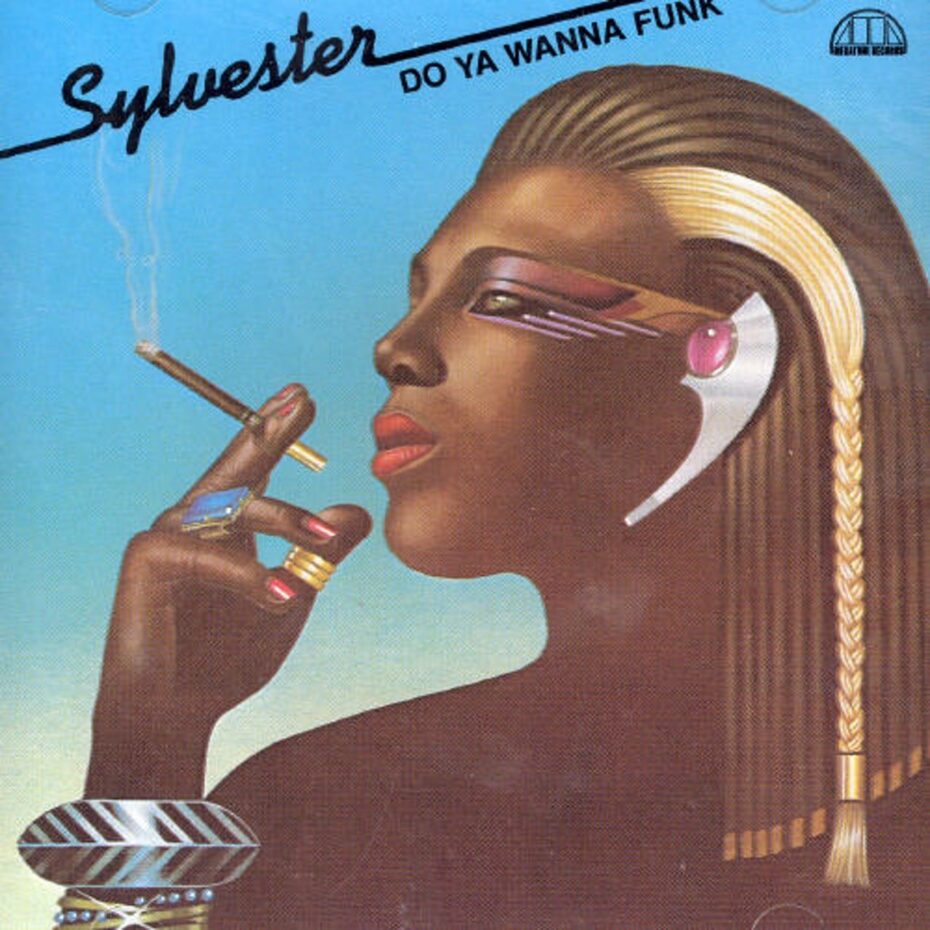

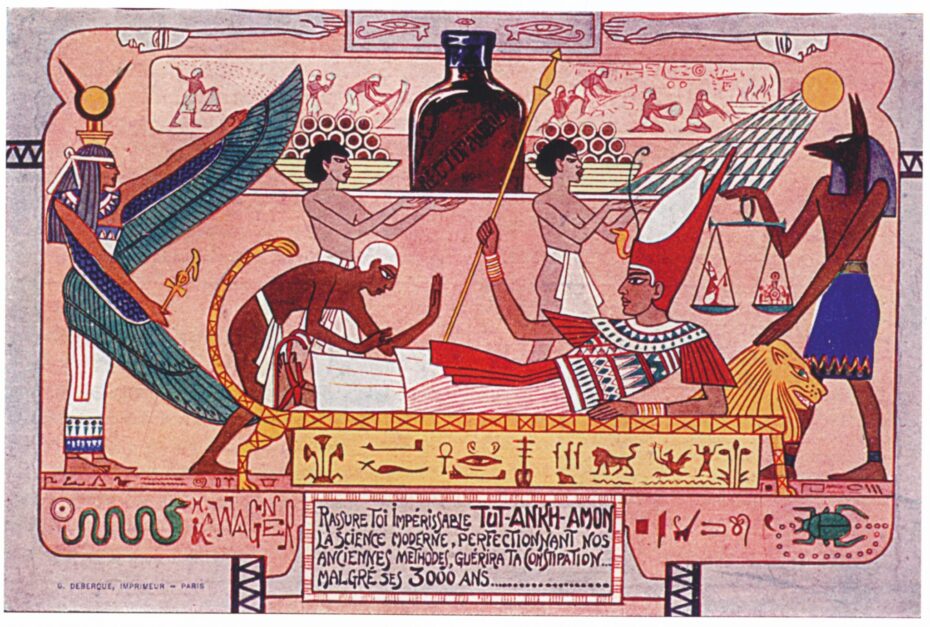

Advertisers jumped on the bandwagon, using Egyptian scenery and images of King Tut to evoke luxury and style, from women in flowing white robes fanning themselves in perfume adverts to women selling soap with sarcophagi. Beauty also got an Egyptian makeover, with eyeliner making a comeback and the iconic bobbed haircuts of the 1920s flapper were directly inspired by the depictions found on Egyptian tomb frescoes. Tutankhamun’s tomb was filled with chests containing shawls, sashes, gloves, sandals, headdresses, and sure enough, fashion houses scrambled to accessorise women with scarab brooches, serpent belts and hieroglyphic bracelets. The Textile Color Card Association of America even based its 1923 palette on the discoveries of the king’s tomb.

Films like The Mummy (Freund, 1932) starring Boris Karloff–regarded by many as one of the finest horror films ever made set off a new trend of mummy-themed horror films. Agatha Christie’s Death on the Nile (1937) also helped continue the momentum of Egyptomania, and in 1963, the blockbuster Cleopatra dominated the box office, proving that Egyptomania was far from over. And if you spend some time in the casinos and hotels of Las Vegas today, you’ll be reminded that it never died.

It is believed that only 30% of Egypt’s monuments have been uncovered, meaning there’s so much more we still don’t know about the country’s fascinating ancient history. Even in 2021, the mummies and remains of 18 pharaohs and four queens were paraded across Cairo in an historic procession, transported in an oxygen-free capsule in customised golden carriages drawn by horses to the newly-opened National Museum of Egyptian Civilization. Egypt’s tourism sector is seeing remarkable growth, with visitor increases of up to 85% in the last few years. More than a century after the first tourists began clambering up the pyramids of Giza for afternoon tea, Egypt is claiming its spot once again at the top of travel “hot lists” claiming that “Ancient Egypt is New Again“, and emerging as a bucket-list favourite with travel influencers on social media. It would appear that another wave of Egyptomania is already upon us, but let’s just hope that in this era of decolonizing the colonial mindset, we’ll be better guests.