We live in landscape narratives — places where stories are embedded in the land itself, entangled in the vegetation or built into the architecture. A winding road, a tower, a house under construction or falling apart — in all these we find stories at work. Gardens are perhaps the ultimate landscape narrative where stories may be told through the arrangements of plants, pathways, statues, fountains, or architecture upon the natural features of a site. The great Italian architects of the sixteenth century purposefully inscribed narratives in their gardens to create story gardens, and this tradition has continued to inspire artists in our own era. The creators of these gardens envisioned them as picture books to be read with the intellect as well as the senses, in which the visitor was reader, character, narrator, quester, enactor. Not intended merely as venues of entertainment or escape, these gardens are meant to elevate the spirit, heal the body and soul, and sometimes even alter the destiny of anyone venturing there.

The making of this magic lay in the wise combination of landscaping, vegetation, water, and decoration often governed by occult symbolism. The point was to create an immersive experience that could lead you to self-knowledge, cast you into a trance-like state, or enhance your understanding of your place in the cosmos.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the key to this transformative power was the occult doctrine of signatures, which make themselves known through visible signs, or signatures. The color red for example, irradiated the power of the planet Mars in blood, plants, in iron and other minerals, in objects made of iron like knives or swords, and activities and things pertaining to the domain of the Roman god Mars or the astrological sign of Aries.

Designed for a specific patron, a garden would often include multiple references to the patron’s horoscope, family history, marriage, and career. By incorporating planetary influences into the garden’s design through the doctrine of signatures, an unfortunate astrological aspect in the patron’s horoscope could be corrected, an illness healed, bad karma blunted or overcome. Plants were chosen for their healing properties or symbolism. Statues could sometimes be commemorative or educational, illustrating scenes from mythology, the patron’s personal history, or historical events, but they also transmitted positive influences through their symbolic or astrological value. They could even be made to produce sounds through special mechanisms. The striking placement of a human or animal figure in a particular setting could also have a powerful emotional impact creating in the viewer a keen sense of identification with the figure or the scene. Fountains or bodies of water present in a garden are also infused with spiritual significance – as sources of rejuvenation or life-giving forces.

Among the many possible narratives woven into Italian story gardens, themes of rebirth, return to paradise, Pan and his nymphs, the Great Mother, quest and the birth of the cosmos remain supreme. Entering such a garden is like immersing yourself in a dream; every detail has been designed to catapult the visitor into a state of heightened awareness.

Paths to follow or stray from may lead to surprising discoveries. The use of perspective in the layout of pathways might pull you towards a vanishing point. A looming statue beyond a bend in the path may evoke fear, wonder, or religious awe. Mossy steps leading down into a dim cavern might convince you that you are descending into the underworld, where eerie statues and candlelight reinforce this illusion. A steep ascent might challenge your spiritual stamina as you climb towards a chapel or temple. You might lose yourself in a labyrinth or find yourself pushed out from a claustrophobic corridor of interwoven branches into a wide-open vista, mimicking the experience of being born. A fountain splashing nearby suggests the waters of the spirit in which you may now be baptised. As you follow these narrative paths and receive the influences planted there for you, you become the performer of the garden itself, the hero or heroine of its story.

Many gardens in Italy, high on sun-baked hills or buried deep in lush ravines, embody this garden magic, as Edith Wharton once defined it. Near Rome, located in Etruscan settings, are three easily accessible story gardens which promise unique opportunities for enchantment.

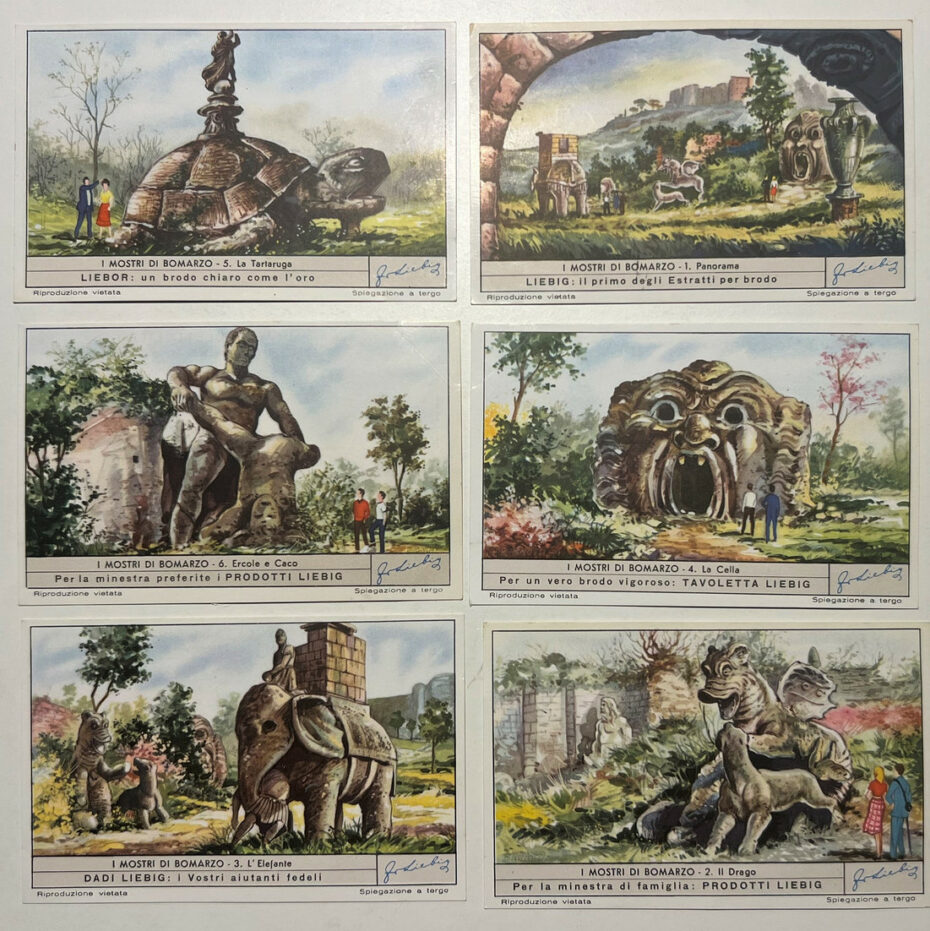

The Sacred Wood of Bomarzo

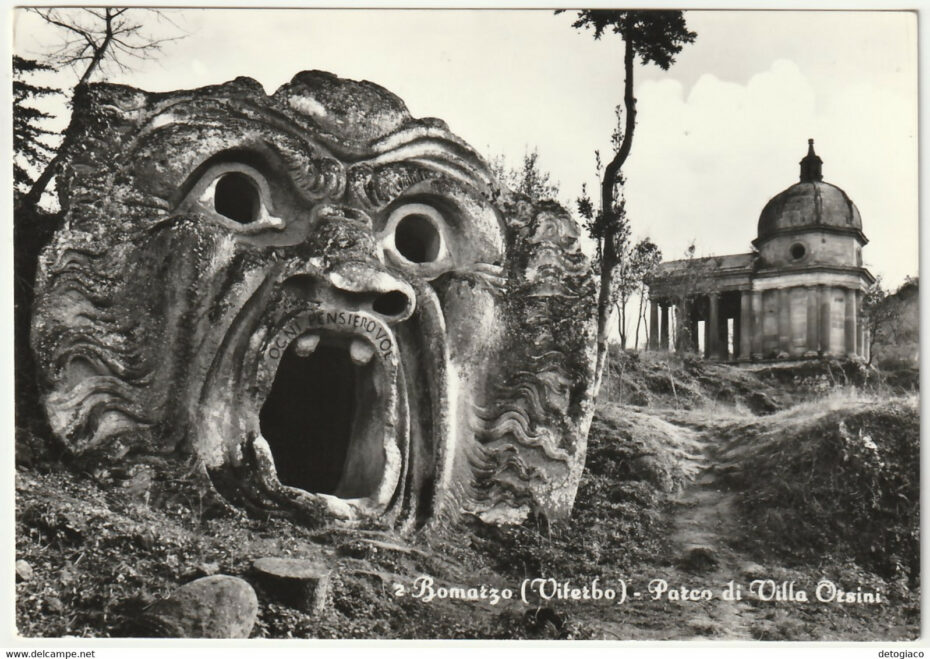

Located in the town of Bomarzo, near Viterbo, this garden was built in the mid-sixteenth century by Prince Pier Francesco Orsini, aka Vicino, and is believed to have been designed by Pirro Ligorio. It too is conducive to dreams, but of a different kind. Not for nothing is it also called the Park of Monsters.

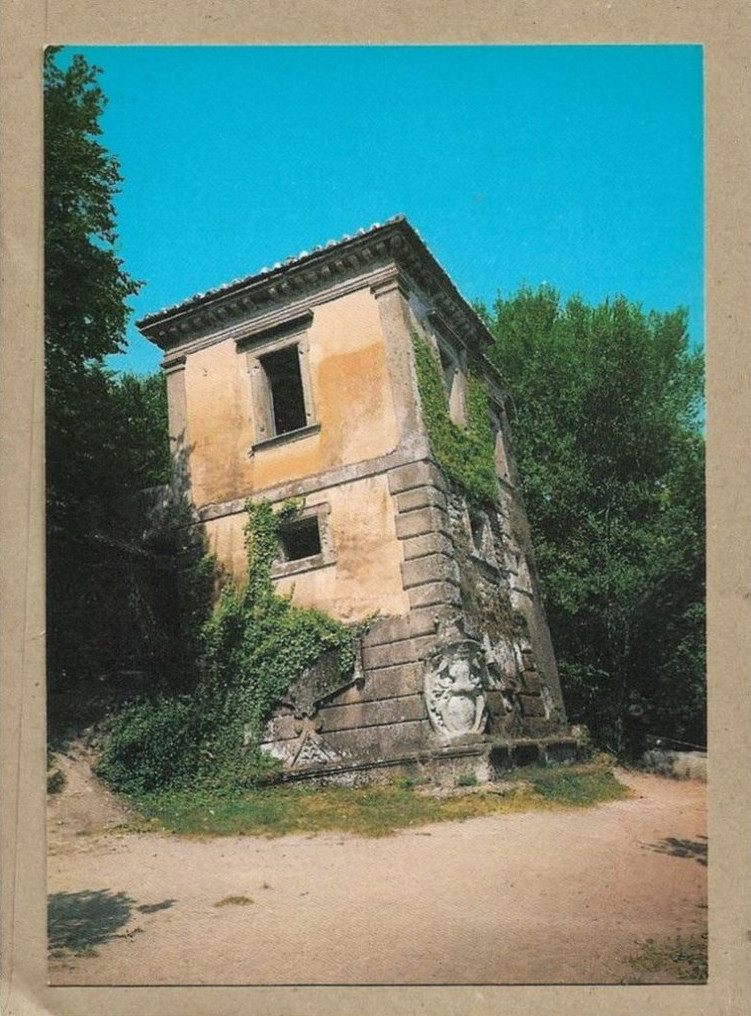

Like Villa Lante, the Sacred Wood defies the conventions of its time by not being near a villa or palace. Set midway down a gorge, distant from the Orsini Castle up in the town, it was not meant to be an appendage to a princely home but an “experience” unto itself. At Villa Lante, the atmosphere shimmers with sunlight reflected on water in the dappled shade of enormous trees, but here it is gloomy; the park is in perennial shadow. Here the itinerary leads the visitor down into a vision of hell. It is believed that Vicino created the park in memory of his deceased wife and that it represents his journey through mourning.

Near the entrance, a sphinx announces the enigmatic nature of this place.

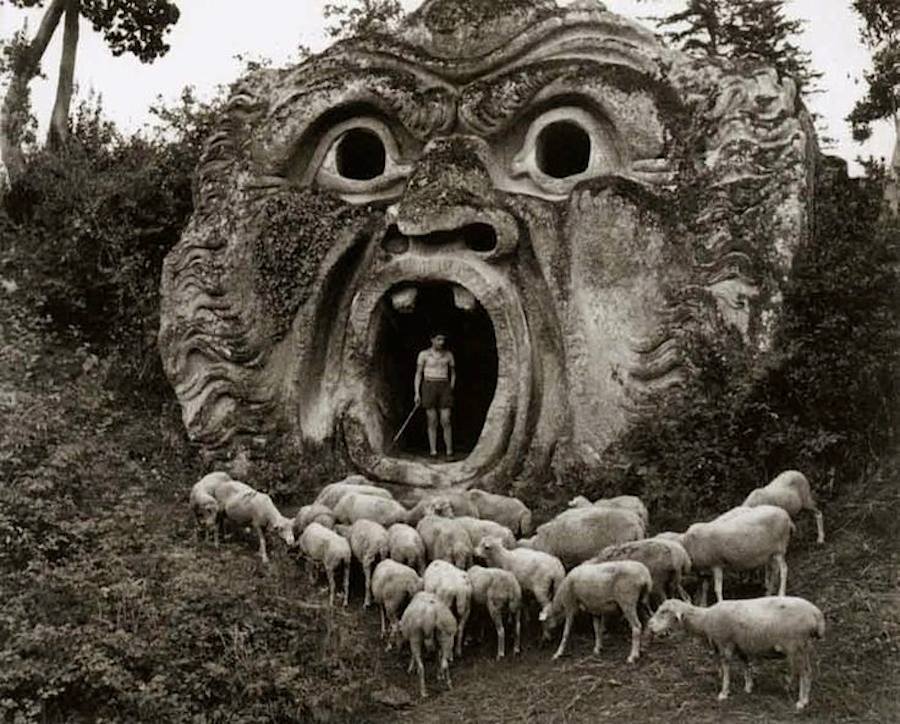

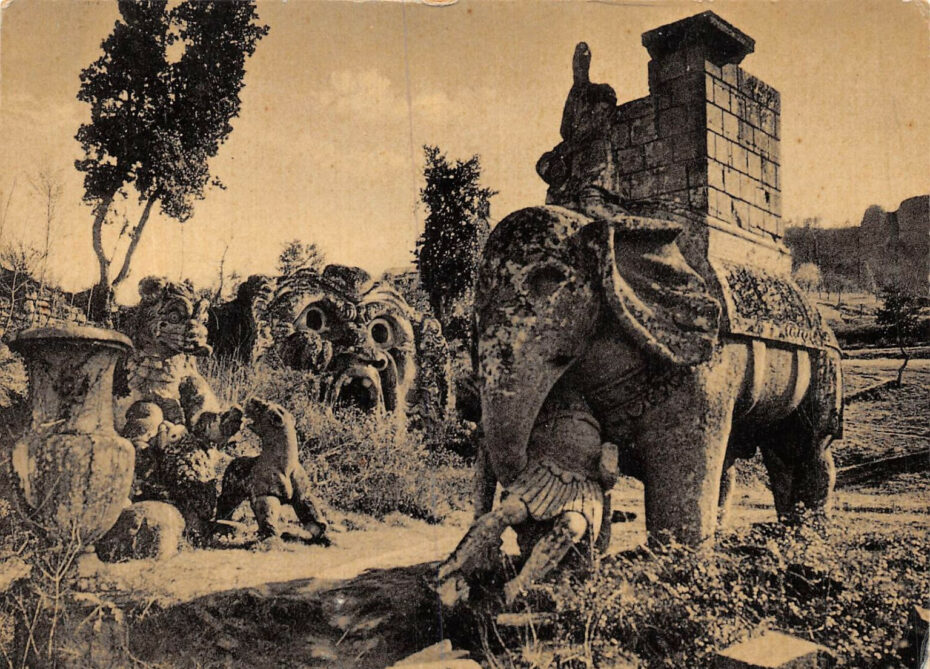

Further ahead, Cerberus, the three-headed guard dog of Hades, marks the threshold of the Underworld. Along twisting paths and crumbling stone stairways, you encounter bizarre creatures randomly carved from outcroppings of rock: giants in combat, an elephant trampling a soldier; a cave with gaping mouth, a sexy mermaid. Blistered with lichen, half-hidden by ferns, these statues of grey tufa seem to have sprung up from the earth, shaken free by a cataclysm. Cryptic inscriptions throughout the park inform us that Vicino wanted visitors to be shocked and stupefied by them.

After aimless wandering, you reach the center of the wood where two figures stand in stark relief: a paunchy Pluto, king of the Underworld, frowning from a mossy fountainhead, and Persephone, goddess of springtime, Pluto’s captive wife, lounging opposite. They hold the key to the mystery of Bomarzo, for they invite the visitor to re-enact a myth: Cybele’s search to rescue her daughter, Persephone, from the Underworld. In the religious rites of Ancient Greece, Persephone’s release from Hades symbolized the soul’s liberation, a second birth. By rambling through this park in Cybele’s footsteps, you have, according to Vicino’s secret plan, been symbolically reborn.

In Vicino’s “Sacred Wood” Persephone may be freed from the Underworld only after the seeker has lost his way in the forest, confronting sculpted images of terror, lust, and rage at every turn. These grotesque statues represent the darker side of the human psyche which must be transformed through the alchemical process before gold can be made, or spiritual regeneration attained.

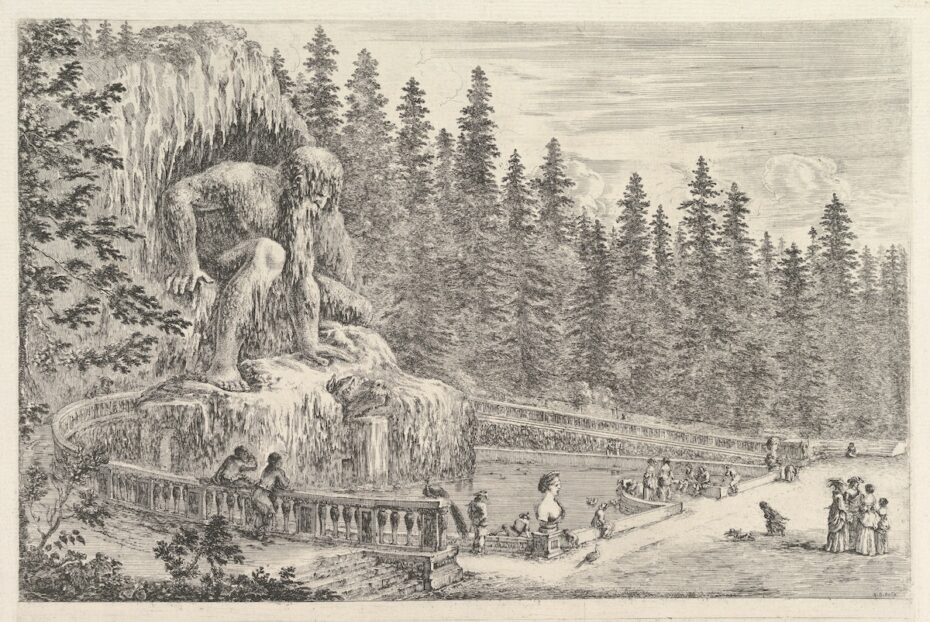

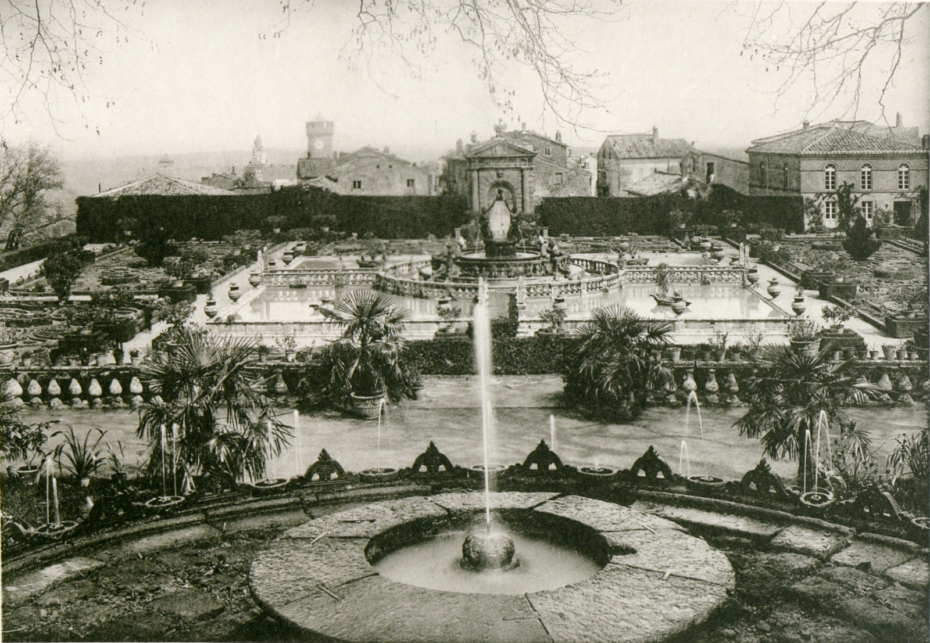

Villa Lante

This sixteenth-century garden in the town of Bagnaia near Viterbo, designed by Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola for Cardinal Gambara depicts the birth of the cosmos and the return to innocence through the element of water. The name is actually misleading, as there is no villa at Villa Lante – the Cardinal had spent all his money on the garden, and didn’t have enough left to build a proper residence. Villa Lante is divided into two distinct precincts: a cultivated area and a wild one, or bosco, representing nature in its wild state. Situated on a steep slope, the cultivated garden is structured on several tiers, each with a monumental fountain. At the top stands a series of grottoes where water bursts through a gorgon mask into a fern-fringed pool symbolising the source of all life and the primeval innocence of every human being. Midway down, the water bubbles through a long stone trough, notched like a spinal column, guarded by a giant crayfish, Gambara’s heraldic symbol.

Streaming downwards amid explosions of pink and purple hydrangeas, it cuts a deep groove right down the middle of a huge stone slab, which is really a picnic table, and the groove brimming with running water was used to cool wine. At the very bottom of the slope, the water flows into a fountain set dead center of a stark geometrical boxwood maze representing the beautiful prison of the rational mind.

The sparkling thread of water wending down from the grotto to the maze tells the story of the descent of divine energy and its final confinement within a seductive but artificial form. You enter the garden at this lowest level where you are urged not to dally in the maze, but to live the story backwards, by retracing the water from fountain to fountain all the way up to the source. Once you reach the top, you return to the primordial state of innocence and pure awareness.

While the maze at the bottom enchants us with its exquisite geometry, here at the top, nature expresses itself freely in the water spurting forcefully through the gorgon’s lips. The sound as it surges forth from the mask is hypnotic, and the deep rich colour of the water in the basin, tinted green by the ferns, is eerily unreal. Unlike the maze, this space is to be lived with the senses, not with the mind. It is a space conducive to dreams and repose.

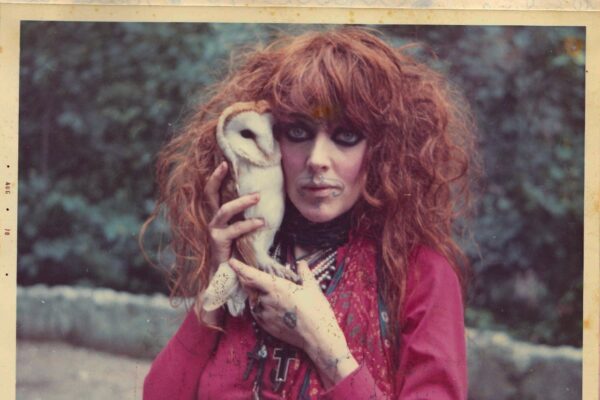

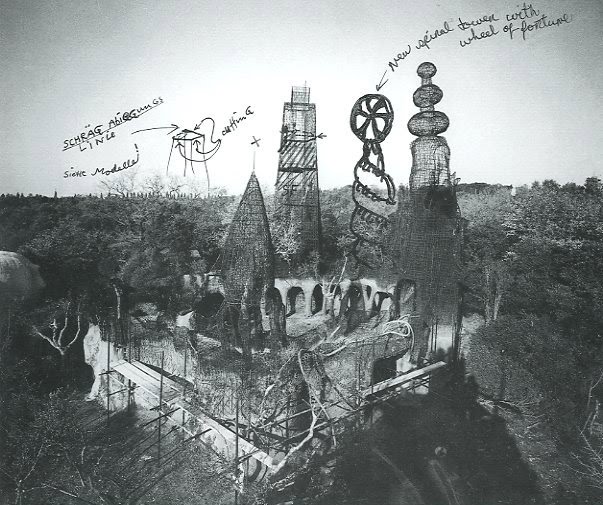

The Tarot Garden of Niki de Saint Phalle

This amazing garden is located near the Tuscan sea town of Capalbio, created by French-American artist, Niki de Saint-Phalle in the 1970s. Bomarzo is among several influences contributing to her vision. But whereas Vicino’s garden was intended to “unsettle” its visitors by projecting the disturbing contents of the psyche upon its eerie stone figures, de Saint Phalle’s Tarot Garden, combining architecture, sculpture, mosaics, calligraphy, mythology, and feminism, conjures an atmosphere of scintillating color, fantasy and pure joy. De Saint-Phalle considered it her most important work, a joyland, and proof that women artists can work on a monumental scale just as men do.

Off a dusty country road not far from the sea, an arrow points towards a hill where glittering towers in day-glo colors thrust up amid live oaks and olive trees. After climbing a steep slope in the scorching sun, you step into a psychedelic dream come true. A giant turquoise mask with water gushing from swollen purple lips forms the phantasmagoric gateway into a wonderland where twenty-two sculptures, towers, fountains, and other buildings, represent the Major Arcana of the Tarot, resembling the exotic rides of a crazy carnival.

Vibrant lollipop colors delight your eyes, bedazzled by thousands of mirror tiles covering every surface, interspersed with brilliantly colored mosaic fragments. Here you meet the Magus, the Priestess, the Emperor, the Hermit, the Reaper, and the Hanged Man, while puzzling over inscriptions in Ancient Greek, Egyptian hieroglyphs, in French, English, Italian, drawn from the great spiritual traditions of the world. The Tarot figures chart a path of initiation, from the magus to the fool and back. For Niki de Saint Phalle, as for poet T.S. Eliot, the Hanged Man–suspended by his foot– was the key figure of the Tarot, representing the artist, who looks at life from another perspective.

Perhaps the most astonishing sculpture is the sphinx– a huge crouching female form with enormous breasts. The sphinx is actually a house where de Saint-Phalle lived while working on the garden. Inside one breast was her bedroom; the other, her kitchen, these too covered with mirror mosaics.

De Saint-Phalle’s personal story is traced in fragmentary form through the many inscriptions, cartoons, and pictures decorating the walls, telling how this garden was made. Like Vicino’s Sacred Wood, it was born of suffering, as well as dreams. During the 1950s, de Saint Phalle was hospitalised in a psychiatric clinic after a suicide attempt, where she was subjected to several sessions of electric shock therapy. While in the clinic, she dreamed of making this garden, and wanted it to be a place of healing. Two decades later, with the help artists, friends, locals, celebrities, and even French government officials, she succeeded.

In her letters, de Saint-Phalle remarks that the twentieth-century vanished while she was working on her garden, as it does for its visitors today who wander from sculpture to sculpture, creating their own tarot readings. Perhaps the eeriest sculpture is the arcanum of death – a golden woman with skull face astride a blue horse, trampling creatures on a green sea beneath her. As you come across her in the blazing sunlight, she takes your breath away.

Returning again and again to the garden, you can ponder the inscriptions on mosaic tiles where the artist recorded snippets of her life, snatches of poetry and philosophy, and left fragmentary clues for us to follow, along what she hoped would be path of healing.

All three gardens have one aim, to make us whole again, to immerse us in a place not of this world, outside of time and yet accessible in the physical world: to challenge our sense of what is real and what is possible and to celebrate the joy of creation.