Get your sea legs ready, we’re setting sail for the bygone days of wild seafaring in search of a little-known piece of nautical history: the castaway depot. Also known as castaway huts, castaway depots were small shelters strategically placed on isolated islands by governments or maritime organisations and equipped with basic supplies and tools to people who survived shipwrecked and found themselves stranded. These little isolated huts tell legendary stories of bravery, adventure and loss, passed down for generations, but was has become of them? Are there any left? Have they all been converted into Airbnbs? We decided to find out…

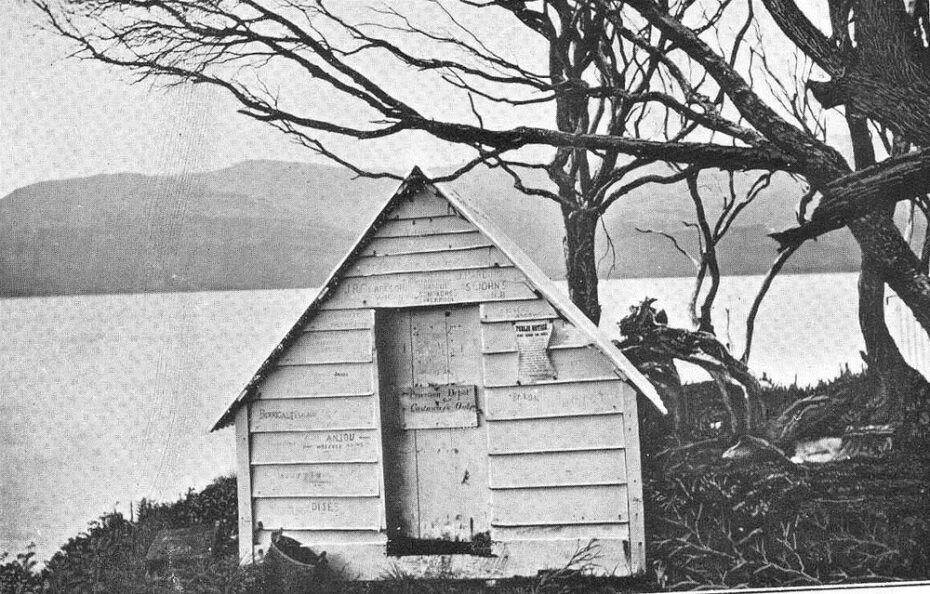

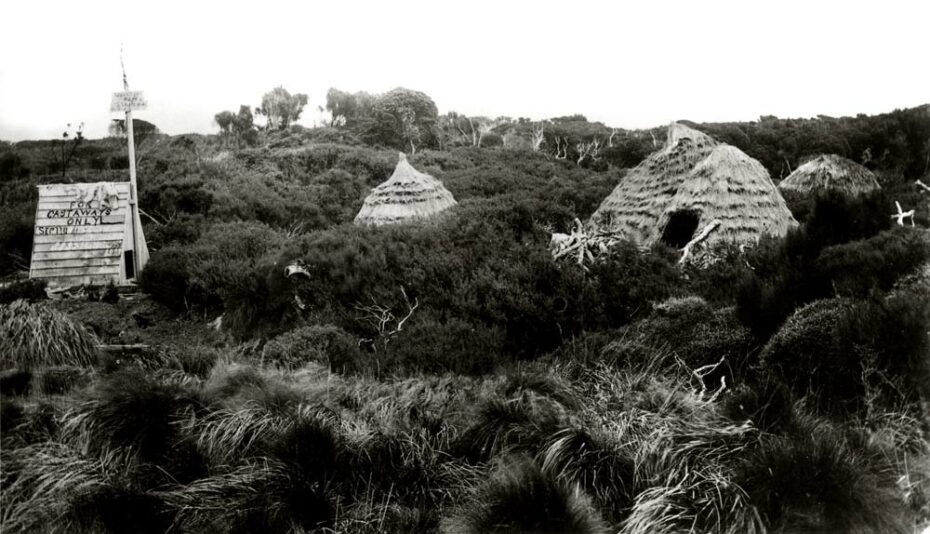

The use of castaway depots began in the 19th century and continued into the 20th century and typically contained items such as food, water, medical supplies, and other essential items that could help stranded seafarers survive until escape or rescue. The idea was started by the New Zealand government in the 19th century when it erected several depots scattered across the Chatham, Kermadec, and the Subantarctic Islands. One particular island, Disappointment Island, had been named as such due to the frequent occurrence of shipwrecks on the island and its extreme lack of resources. The small hut-like structures could withstand high winds and hurricanes as best as possible for as long as possible in the hopes of saving the lives of potentially shipwrecked men.

In addition to food, shelter supplies, tools, and other necessities, the New Zealand government released various species of animals onto the islands to propagate and become an ever-growing food source for the shipwreck survivors. Pigs were the first animal released on the Auckland Islands in the 19th century, and they were followed by goats and sheep. There is also record of rabbits being released on Enderby and Auckland Islands in 1840 and a decade later on Rose Island. Cattle were farmed briefly on Enderby Island and adapted to eating kelp and seaweed.

At the time, there was no understanding of the effects of introducing non-native species onto islands that often possessed their own unique wildlife. Notable ecological disasters ensued, particularly with animals with such voracious appetites as goats and rabbits. It is safe to say there once existed more native species of flora and fauna on those islands that were eaten into extinction before they could be officially discovered and given a proper classification. Ironically however, and consequently, because of their isolation, many of these small populations of animal species, such as the Auckland Island pig, Enderby Island cattle, and the Enderby Island rabbit retained rare genetic characteristics. Due to their isolated genetics, some of these animals were used in research for diseases like diabetes. Most of these animals died, but some survived into the 20th century.

Perhaps some of the most notable shipwrecks that occurred on these islands were notable for the extreme limits the surviving crew members were pushed to and how they managed to survive and escape before death by any number of ways claimed them. One of the most harrowing stories related and earliest recorded shipwreck to these islands came before the introduction of castaway depots and was likely the very reason they were instituted.

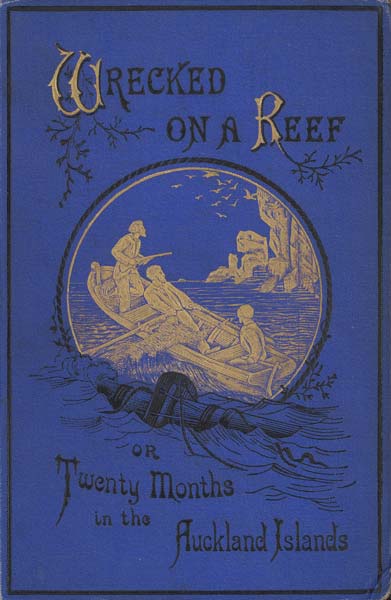

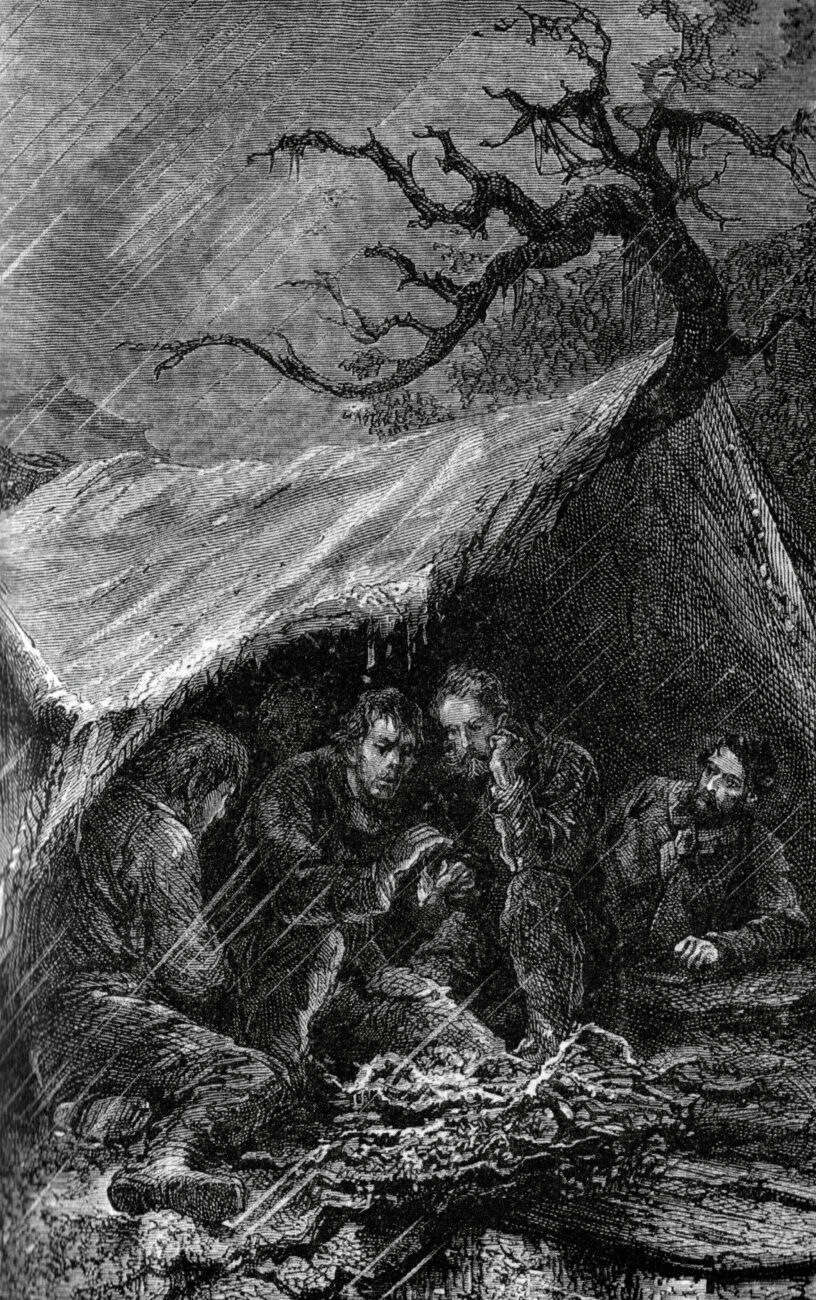

In 1864, the Grafton ship embarked on an expedition to Campbell Island in search of large tin deposits, led by businessman François Édouard Raynal, captained by Thomas Musgrave, sailing with a crew of five from Sydney harbor. The survey for tin was a failure and on their return voyage via the Auckland Islands, the Grafton was struck by a gale in one of the islands’ sounds and ran aground on a rocky beach of one of the Auckland Islands. The crew made it to shore with a great amount of equipment and provisions from the wreck. Though their provisions were only enough for two months, the entire crew of the Grafton survived for 18 months by rationing and supplementing with seal meat, birds, and fish. To ward off scurvy, Raynal brewed “a passable beer” from Stilbocarpa rhizomes (a native flowering plant), which were then fermented in their own sugar.

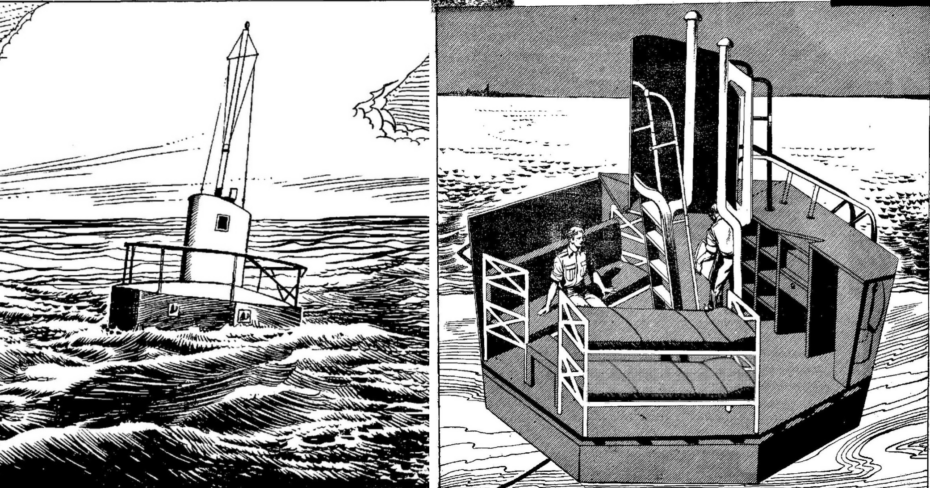

They made temporary structures from spars and sails before later building more permanent cabins from the wreckage and local stone. They passed the first year making clothes from sealskin, carving a chess set and domino set, as well as providing reading classes. Musgrave and Raynal assumed Raynal’s business partner would send out a search vessel to investigate once their approximate return date had passed, but after one year with only a single ship sighting, a decision was made to construct a vessel that could carry them to New Zealand. Using the tools they had salvaged from the wreck and a pair of blacksmith’s bellows fashioned from scrap metal, they enlarged the original ship’s dinghy by raising the gunwales and adding a false keel.

When they tested their creation, it was too unstable to hold all the men which meant that two men were left behind until they could return to rescue them. After five days of harsh weather, the three men made it to Stewart Island where a Captain Cross brought them to his home for a bath, a meal, and rest. After sailing to a larger island and raising money through public funding, Raynal and Musgrave were able to return to the island to rescue the remaining to crew members. Musgrave and Raynal authored books about their experiences and several artifacts, including Raynal’s handmade bellows, are in a collection at the Melbourne Museum.

Incredibly, four months after Grafton initially ran aground on the main island of the Auckland Islands, another ship, the Invercauld, had wrecked on the opposite end of the main island and neither group of sailors knew of the other’s existence until Captain Cross of the Flying Scud sailed back with Raynal and Musgrave to rescue the two remaining men. When the Flying Scud anchored at Erebus Cove, they found the body of a man, lying long dead beside the ruins of a deserted settlement, on a slate next to him was some illegible writing.

The Invercauld had set sail with a crew of 25 men, but by the end of only three months (in contrast to the Grafton’s 18 months) all supplies had been lost or exhausted, no animals remained to be hunted, and only three out of twenty-five men remained and were rescued by a Portuguese ship called the Julian. One of the survivors, Robert Holding, reported that at least one crew member of the Invercauld had resorted to cannibalism after an altercation between two men had left one of them dead and it was then discovered by Holding that “Harvey had been eating some of Fritz”.

There are at least five notable shipwrecks that occurred on the Auckland Islands in which all or most of the crew was saved by the provisions left in castaway depots. The last shipwrecked crew to survive as castaways was the crew of the French barque President Felix Faure that was wrecked off the North Cape of Antipodes Island in 1908. The entire crew made it to shore close to a castaway depot. When all the supplies had been depleted, the crew hunted albatross, penguins, and a single calf; the sole remnant of the cattle that had been set ashore with other supplies by the Hinemoa, a New Zealand government service steamer that serviced and patrolled New Zealand territorial waters. The crew of was rescued by the HMS Pegasus and eventually made a successful return journey to France via Sydney.

The implementation of castaway depots was not limited to the southern hemisphere. The US Navy stocked Adak Island in the Aleutians with 50 head of caribou in the 1950s. Small hobbit-like shelters were scattered around the island which had sleeping bags, blankets, and cans of sterno inside.

In the late 19th century, the United States Life Saving Service also built a series of castaway depot-like stations called The Houses of Refuge along the coast of Florida to shelter ship-wrecked sailors. These houses were built by civilian contractors who were required to take their families to help with the duties and prevent the very real consequences of loneliness in such isolated locations. As a part of their contract, the brave keepers, also known as surfmen, were required to “search the beach for shipwrecks and persons cast ashore” immediately after storms.

No matter what else happened in their daily lives, the surfmen and keepers of the United States Life-Saving Service lived for – and feared – shipwrecks. The adrenaline-pumping first few moments after the words “Wreck ashore!” rang out reaffirmed for each man why he had chosen this career. The noble nature of the work, the chance to wrestle lives from the grips of the sea, to save a life, enflamed the spirit. Sometimes those rescues were completely successful; sometimes victims succumbed; sometimes the rescuers themselves needed rescue. The following shipwreck stories get down to the basics of the Life-Saving Service and its mission: to save the lives of men and women imperiled upon the sea.

U.S. Life Saving Service Heritage Association

Their station house was equipped with cots and extra supplies to provide food and shelter for up to twenty castaways. Built of Florida pine, each one was surrounded by a wide covered veranda, quite the improvement from the stark castaway depots built by the New Zealander government. Many of these stations were in service until 1915 and even later. Canada also had similar depots on small islands in British Columbia, known as Shelter Sheds, stocked with maps, charts and survival information in several languages. In World War II, the Luftwaffe developed rescue buoys (Rettungsboje) to provide shelter for pilots shot down or forced to make an emergency landing over water. The British had an equivalent called Air-Sea Rescue Floats which were equipped with food, cooking facilities, signal flags, a radio, six bunks, clothing, water and first aid.

If you fancy a visit to a castaway depot, there is one refuge station called Gilbert’s Bar House which is still standing in St. Lucie Inlet, near Stuart, Florida. It was a castaway service station from 1876 to 1915 until it became Coast Guard Station no. 207 which was used until the 1940s. It is now a museum open to visitors and offers various historical re-enactments for your viewing pleasure year-round.

Despite having saved many a sailor’s life throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the use of castaway depots has all but disappeared with the invention of modern communication devices and modern navigation. That isn’t to say that people don’t get lost at sea or stranded on islands, but it is statistically less likely and as the world has become more inhabited, there are fewer deserted islands to be shipwrecked on.

Fancy a Robinson Crusoe experience yourself? Skip the shipwreck and the hassle of keeping scurvy at bay at a hidden, eco-friendly secluded beachfront “castaway resort” on the Croatian island of Hvar – spacious wooden huts, hammocks and snackbar included.

Or if you prefer to try the other side of the adventure, join Bark Europa for sailing cruises to the Antarctic aboard the EUROPA, built in 1911 to serve as a lightship on the river Elbe in Germany and brought to the Netherlands in 1986 to be completely rebuilt as a barque (three mast rigged ship). Join the crew and learn to sail this wooden tall ship with a crew of people just as adventurous as you. If armchair travel is more your speed, enjoy the captivating photography of New Zealand and the Subantarctic Islands through the talented eyes of photographer John Bozinov. Either way, skip the shipwreck.