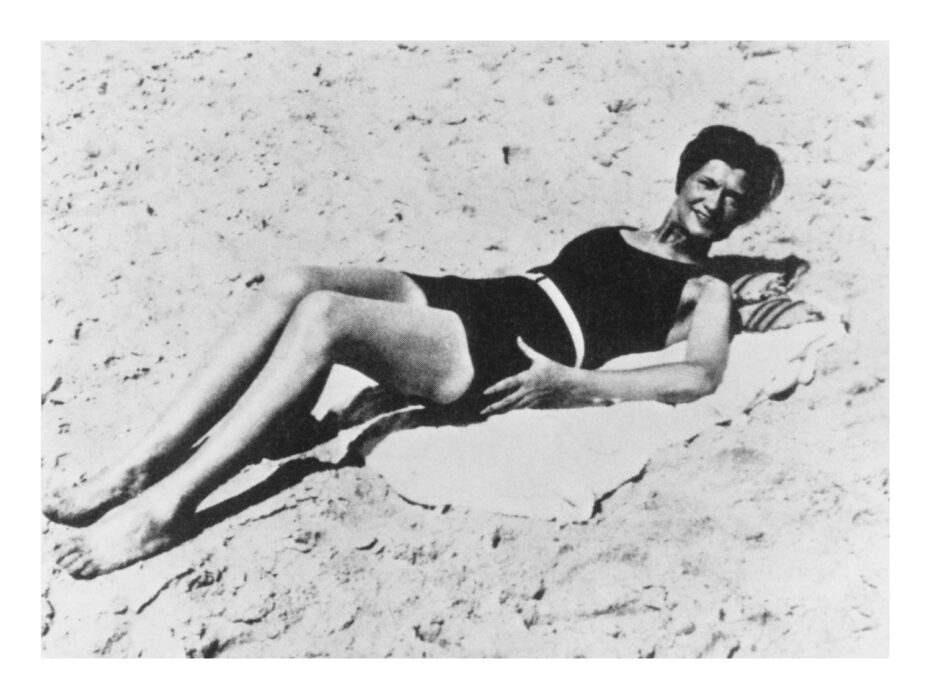

When a lithe ‘It-Girl’ Coco Chanel stepped off a yacht in Cannes with an accidental suntan in 1923, many would argue it was the moment that sunbathing became a cultural phenomenon. Porcelain-skinned flappers everywhere were intrigued by this rebellious new suntanned look sported by the Parisian designer; one that for centuries had been associated with the working class that spent most of their days working outside and exposed to the sun. In Europe and many other parts of the world, fair skin had long been revered as an indication of one’s social status. At this point in history however, skin was now on display perhaps more than ever before in modern western civilisation. With hemlines getting scandalously higher, sleeves boldly slashed, bonnets binned and the coy parasols of the past trashed, women were starting to discover the physical and mental health benefits of a little sun exposure. More and more, “sunlight therapy” was prescribed for almost every ailment from fatigue to tuberculosis. For those who were rich enough, they were also playing more sports and spending more leisurely time at the seashore while on the other end of the spectrum, labourers were moving inside to factories. All standards of beauty are socially-constructed in some way by society, and sunbathing culture has been yo-yoing goes back and forth with it for centuries.

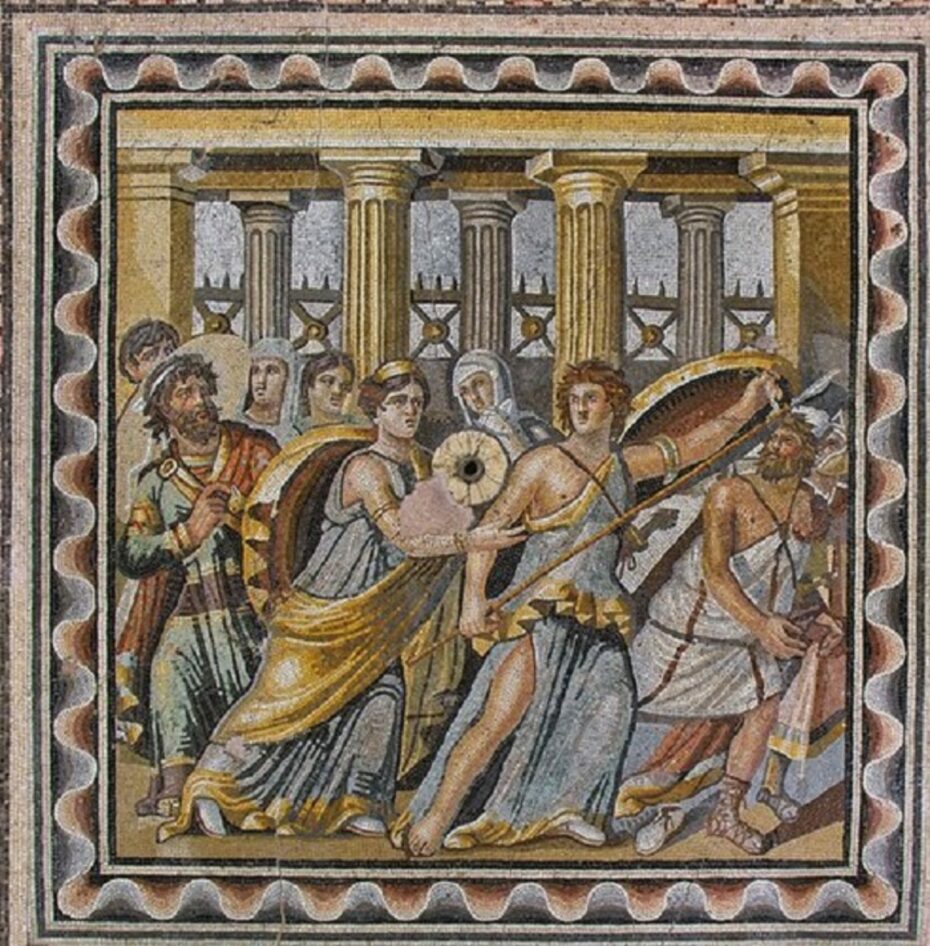

Let’s start with the beautiful tomb paintings of Ancient Egypt and mosaics of Ancient Greece and Rome – regiments of perfect figures, deliberately sized and aligned in status, but also tinted differently to depict various traits, as well as separate the sexes. The women are always shown paler than the men, indicative of a little more time spent indoors and away from manual labour in the fields. But for men, darker skin was a suggestion of bravery and military service while lighter skin indicated weakness. Aristotle wrote that “those whose skin is too light are […] cowardly: witness women”. (It should come as no surprise that Aristotle was also just a little bit sexist).

Following the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 5th century, the brutality of the dark ages and the pestilence of the Middle Ages rather put a damper on tanned skin. The fall of castles and rise of country houses in the 16th century saw the re-adoption of the classical world’s skin manifesto. In hindsight, this was a rather extreme application of the doctrine, potions of lead, arsenic whitening and even leeches were readily applied to the skin to feign idle richness. Being touched by the sun was most unfortunate and unfashionable.

“The European Renaissance was particularly notorious for its blatant colorism”, writes Jeena Sharma for Paper Magazine. “If you thought today’s Instagram Influencers were setting up damaging beauty standards, Queen Elizabeth I, also referred to as ‘The Virgin Queen,’ believed in enhancing the outward appearance of her “virtue” by painting her face flat white, like a ghost”.

For the rich and powerful in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Grand Tours of Europe and expanding empires transported white folks to warm and “exotic” seaside locations, returning with a suntan as a badge of their leisurely pursuits. Following the sun became a more wholesome and healthy pursuit, whether it was Robert Louis Stevenson needing the medicinal Caribbean air or Lord Byron requiring his Italian pleasures.

Women of the Victorian and Edwardian upper classes still ensured to cover up all their exposed bits with head-to-toe ensembles however; gloves, hats and sported parasols to ensure their pallid complexions didn’t incur a single freckle or worse still, a sun-kissed blush. The poisonous lead and arsenic-based cosmetics from the 17th and eighteenth centuries were still very much in use. Science would change all that and soon, the deadly application of whitening arsenic and lead potions in would be replaced with an equally deadly ritual of total emersion in the sun’s radiation.

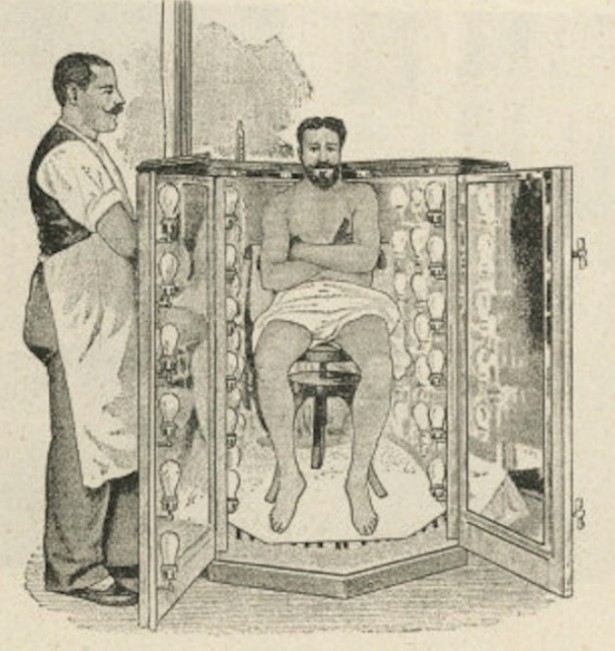

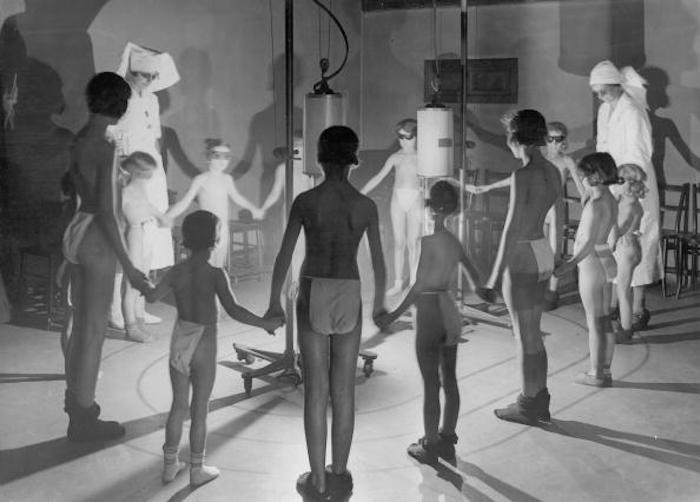

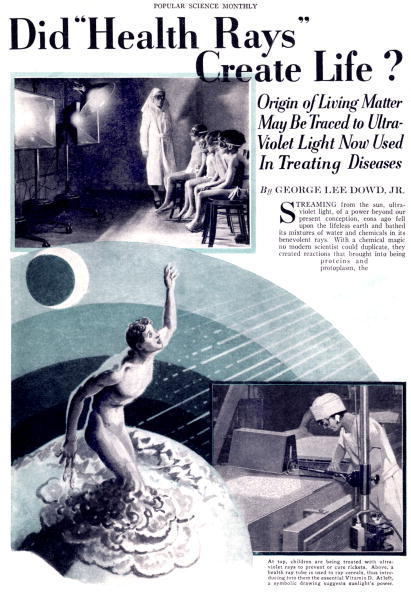

A series of milestones heralded the establishment of the undisputed health benefits of the rays of the sun. By 1890, Theobald Palm discovered just how crucial sunlight was for bone development in children and in 1891, John Harvey Kellogg (yes, he of the corn flake) developed the ‘incandescent light bath’ (which incidentally helped to cure King Edward VII’s gout). In 1903, Niels Fitzen received the Nobel Prize for Medicine for his ‘Finzen Light Therapy’ that was hailed a miracle cure for rickets (a Vitamin D deficiency) and Lupus Vulgaris, amongst other diseases. When a scientific expedition set off to Tenerife to test the merits of ‘heliotherapy’ in 1910, sunbathing was unanimously declared a sensible pastime for the upper crust.

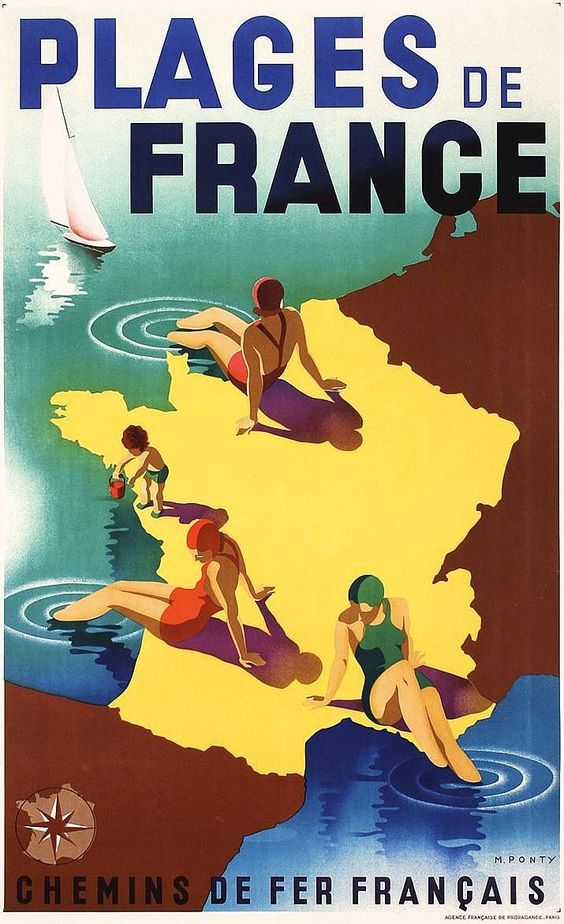

The first rays of a new sun culture splashed across the Mediterranean shores when the rather bold American millionaire couple, Gerald and Sara Murphy came down from dull Paris to the sparkling French Riviera in 1921. Traditionally, Mediterranean France shut up shop in the summer, which was once considered the off-season, would you believe it!

But then came Gerald and Sara; seasoned socialites, athletes, exhibitionists and nudists. Such was their meteoric impact on high society, they persuaded the local hotels to stay open over summer in 1923 – for the first time ever. Relentless entertainers of high society, the great and the good were summoned: Ernest Hemingway, Cole Porter, Josephine Baker, Dorothy Parker, Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau, F Scott Fitzgerald and of course Coco Chanel. All this hit the papers, gossip abounded and being caught in the flesh by the sun was now a requirement.

But for the aspirational fashionista, the vanity factor of soaking up the rays was now about more than just being healthy and staving off tuberculosis. A watershed moment occurred when influential Vogue magazine featured a suntanned model on their front cover in 1927. A new beauty standard was set. And to cement this new trend, Scott Fitzgerald published Tender is the Night in 1934, with its protagonists draping their gorgeous, sun-kissed bodies all over beaches on the French Riviera.

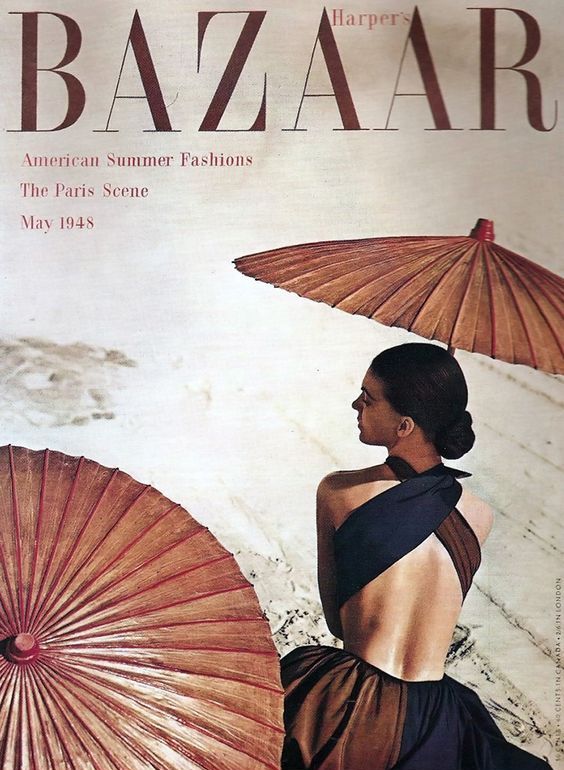

Suntanning was now firmly established as a tell-tale sign of being posh, privileged and beautiful. In Paris, entertainment’s new darling, Josephine Baker, further bolstered the desire for being ‘olive-skinned’, with women from all over idolizing her sultry “exotic” looks. Designer Jean Patou perfectly clocked the zeitgeist and in 1927 gave the obsessed populace Huile de Chaldee, the first mass-produced sun tan oil. An article from a 1929 issue of Harper’s Bazaar showed how being suntanned was now a serious cosmetic consideration, ‘Shall We Gild the Lily? There Is a Technique to a Good Tan—Whether by Fair Means or Fake!’

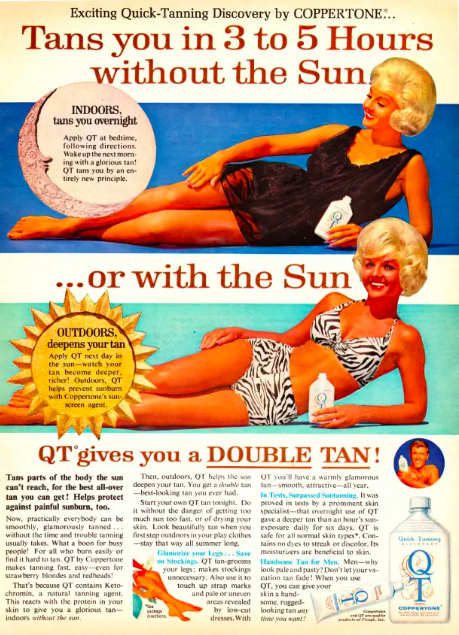

By 1930, magazines glamorised the plight of patients recuperating in the sun at stunning Swiss sanatoriums. By the 1940s, the media widely flaunted sunbathing as a pastime, with one-piece swimsuits shrinking and separating to become bikinis (the first modern bikini made its appearance in 1946). Baby oil was used to grease skin for better tanning during the 50s, and the first self-tan (‘Tan Man’) appeared, albeit with a decidedly orange result. An advertisement surfaced in 1953, Coppertone’s little bronzed, blonde girl with her spaniel pulling down her pants to reveal milky white skin.

With the availability of commercial air travel and colour film in the 1960s, the average British punter of modest means indulged and ventured off to sunny Spain and France and could return with hard evidence. From the days of empires, their overseas contingents were well aware of the harmful effects if over exposed, but alas this never percolated down to the later mass holiday makers. In 1962, sunscreen became SPF-rated but in 1970 quirky innovations like ‘tan-through’ swimwear became available, with fabric covered in thousands of micro-holes to let through the light and guarantee an all-body, even tan to avoid dreaded tan-lines.

When the first energy crisis hit in the 1970s, products for self-tanning, Coppertone’s self-tan and the like, were essential alternatives to perpetuate the illusion of sunny travel. In 1972, Barbie emerged with tanned skin and her own sun specs and suntan lotion. No-sun sunbeds became a global multi-billion-dollar industry, as well as bronzers, accelerators and intensifiers. The 1980s saw a cosmetic boom and together with cheap package holidays to the Mediterranean, tanning remained a focal point of being on holiday.

So where are we today? Fashion contributor for The Guardian, Jess Cartner-Morley, writes than sun-worshipping is once again fading from culture. “Tans are still about status. It’s just that health and wellbeing are flexes of the modern era. Which means lying on a sunlounger with a piña colada has become a retro image, and influencers’ Instagrams are all hikes, visors and salads.” Indeed, SPF products have become an essential among Gen Zers and Millenials as beauty influencers flaunt their favourite suncreens on social media as part of their skin care regimes and tutorials. At the same time however, anti-sunscreen sentiment has also become a hot-button topic on platforms like TikTok where influencers have been controversial campaigns concerning the industry’s use of chemical ingredients including oxybenzone. One thing seems certain: the yo-yo of tanning culture looks set to continue while humans are at the whim of social norms, status and of course, the all-powerful media.