There was a time when a visit to the powder room involved more than a quick tinkle and a dab of powder on the nose. Taking its name from the noble courts of Europe, the powder room was a designated space, in aristocratic houses, for the powdering of wigs that were a little worse for wear after an evening of revelry. The culture of wearing elaborate powdered wigs, or perukes (from the French perruque) as they were known, reached its height (both figuratively and literally) in the 18th Century, having spawned its own vocabulary and encyclopedia, its own artisans’ guild, as well as a new breed of wig-stealing criminals, and our personal favourite, the invention of the mysterious wig hole. Naturally, we need to go down the rabbit hole of historical haircare…

Synonymous with wealth, debauchery and the decadent glamour of royal courts, the irony is that our wig story begins with syphilis. Throughout the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, syphilis was rampant in Europe, often as a result of young gentlemen who were encouraged travel the continent on their coming of age Grand Tour to find worldliness and gain experience in the ‘arts of romance’. Symptoms included weeping sores upon the scalp which caused bald patches or even total hair loss, perpetuated by the misuse of mercury as a so-called ‘cure’ for the disease. When The Sun King, Louis XIV of France (1601-1643) took to wearing a flowing wig, the trend rapidly swept across the European courts, signifying the highest ranks of royalty and nobility. The king had a personal ‘cabinet des wigs’ at Versailles, employing 48 of the city’s best wigmakers. When, after a long and hedonistic life, Louis died at 76 (an impressive age for the time) his body was found to be riddled with syphilis. Over in England, Charles II, who began wearing wigs in a similar style to King Louis XIV and brought the trend to Britain, was famous for fathering the largest recorded number of royal illegitimate children, also succumbed to the disease at the more modest age of 54. The demand for wig-makers had grown so large by the mid 1600s that the first Corporation of Barber-Wigmakers was founded in Paris in 1656.

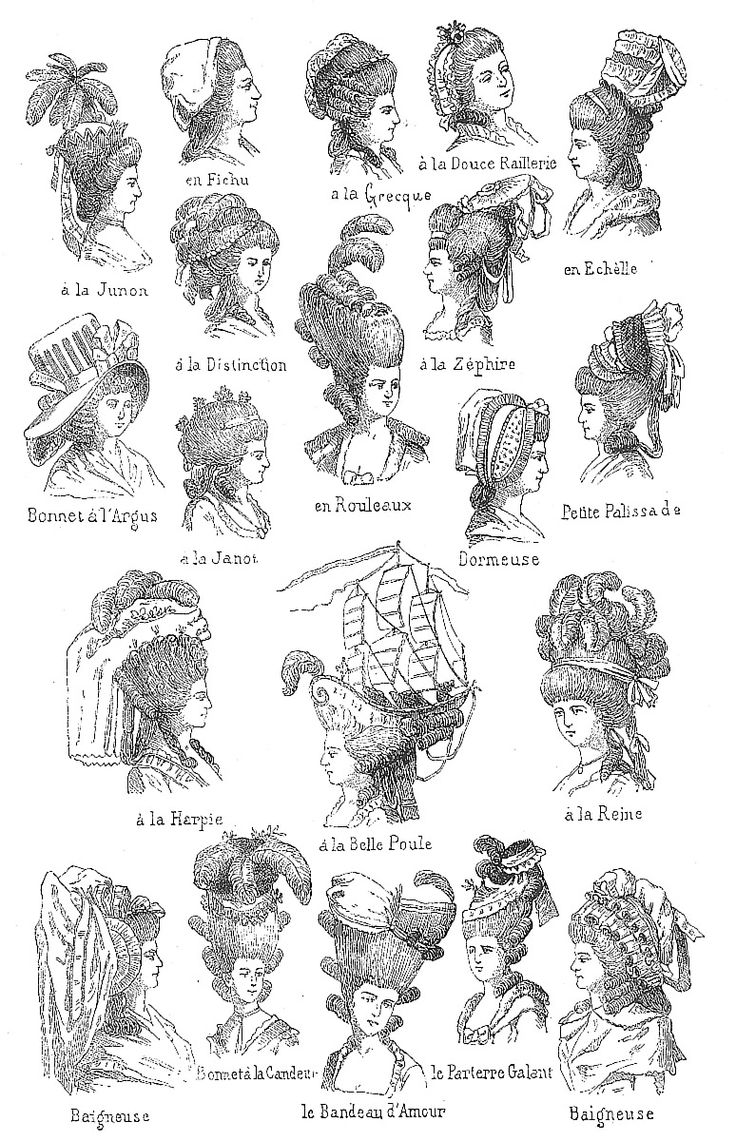

Powdered wigs became de rigueur, white hair being considered particularly noble, and powdered wigs, sporting horizontal curls on both sides, were popular for men. The fashion began to filter through to a wider section of society, namely the wealthy bourgeoisie. Civil servants, doctors, churchmen, and of course judges, all began donning wigs. By 1764, the ‘Perruquiere Encyclopedia’ had been published, listing 115 types of wig, including short ones, those with knots, that with a tail and one which came with a handy purse. According to historian R Grant Gilmore III, some even came complete with live birds. The wigs worn to the coronation of King George III in London in 1761, were so elaborate that they inspired cartoonist William Hogarth to lampoon them in his wonderful engraving the ‘Five Orders of Periwig’.

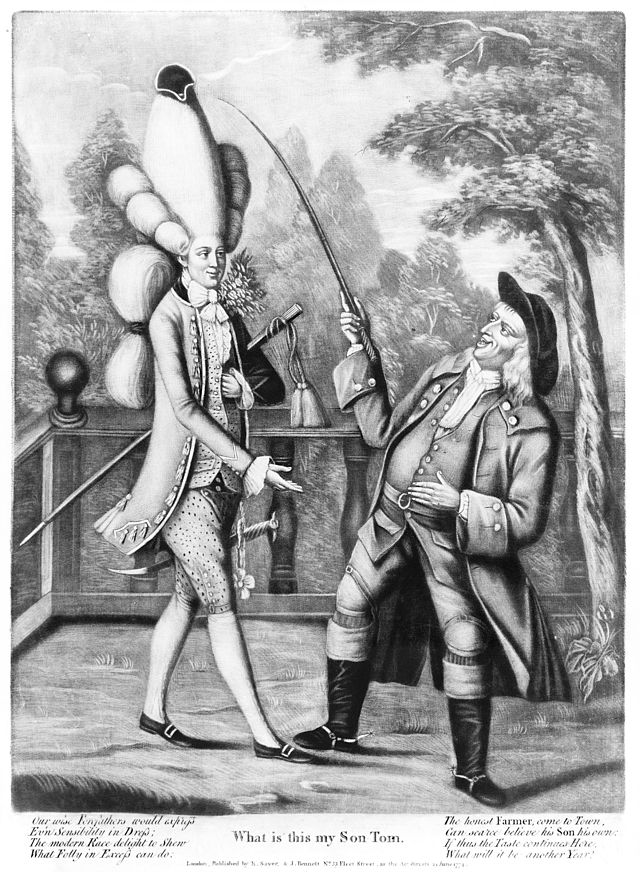

Once wigs and hairpieces had been hijacked by ‘commoners’, the aristocracy determined to be a cut above, and upped their game by going bigger, louder and, inevitably, more expensive. The larger and more ostentatious the wig, the more status its wearer could claim. As an article on bellatory.com so succinctly states, “The grander the wearer, the grander the wig”. The term ‘bigwig’ is still used to describe the rich and successful today.

Up to this point, wigs had been predominantly the domain of men, but with the arrival of Marie Antionette at Versailles, women took centre stage, leaving the men in the wings. Throughout the 18th century, women increasingly adorned their natural hair with hairpieces, bows, flowers, pearls and lace, resulting in the fontange coiffure, “worn curled and piled high above the forehead in front of the frelange, which was always higher than the hair. Sometimes the hairstyle was supported by a wire framework called a pallisade.”

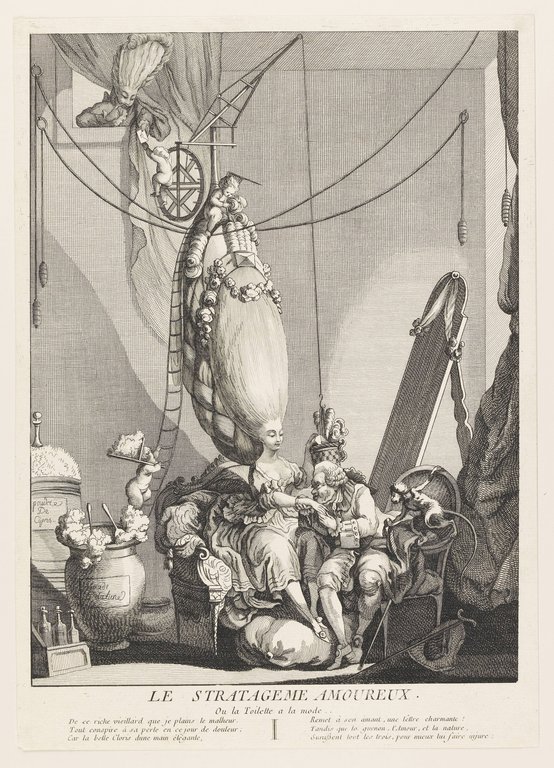

The care and wearing of wigs was not for the faint hearted. A night at the opera was fraught with problems, from how to accommodate a metre tall bouffant in a carriage, to having one’s view completely obscured by the poufs. If one were even more unlucky, they might have their wig ripped from their head by a wig snatcher, a new brand of criminal who stole from the rich and sold wigs to the middle class for a more modest price.

So where did the hair for all these perukes and poufs come from? Cheaper wigs could be made from the hide of cows, goats and sheep, or from horses’ manes, but the majority used human tresses from the poor, peddling their locks to raise some desperately needed funds. Vendors travelled between villages, seeking young or elderly peasant women; silver, white, blonde and grey hair – curly being the most sought after. More alarmingly, hair was also taken from the corpses of prostitutes and criminals and even from plague victims. Once assembled, the peruke was not washable, and as you can imagine, soon smelled terrible. An entire wig care industry developed to try to combat this problem, producing items such as scrapers, salt flasks, lice and flea traps (one advantage was that lice lived on the wig rather than the wearer whose hair was often shorn) and wig curlers.

The wealthy employed a team of staff to dress their hair with lotions and potions, hence we use the term ‘hairdresser’ and not ‘cutter’ today. Pomade was first administered before powder, its name derived from the latin pomum, meaning apple, the ingredient used in concocting the earliest pomades.

Despite generous applications of fragrance, the animal fats used in these pomades must have soon become rancid, further attracting fleas and lice, especially once combined with a ton of powder concocted with wheat flour or dried white clay, which alone could weigh up to two pounds. Powder had to be freshly applied throughout the night by a personal valet.

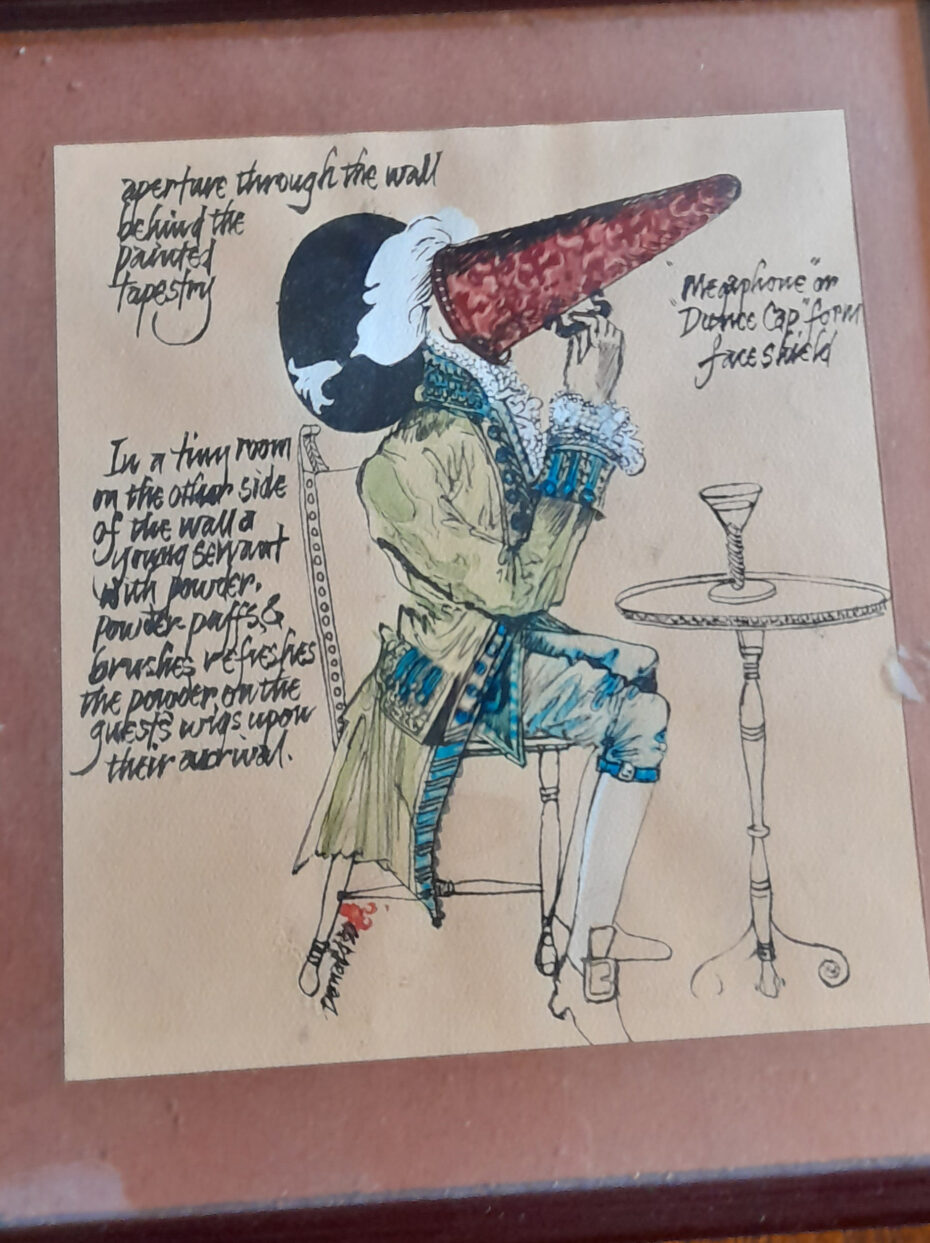

Illustrations show a large funnel placed over the wearer’s face, presumably to prevent inhalation and choking. Powders, usually white, also came in blue, black, pink, lavender, yellow or even red for the most daring.

Some affluent houses even incorporated what was known as ‘wig hole’ into their salons – literally a hole in the wall against which a disheveled guest could simply lean back and wait while a hidden servant’s hands spruced up their tired bouffant. One such hole survives in Southside House in Wimbledon, London.

The 1770s saw a shift from the already extreme fontage, to the absurd powdered edifices that we associate with the Rococo era of the French court that became so symbolic of aristocratic French decadence. Women began to wrap their -already adorned- hair around increasingly enormous gauze structures, called ‘poufs’, becoming so voluminous as to require scaffolding during manufacturing. France’s National Museum blog describes them in an article called Pouvoir et Splendour des Perruques:

“At the height of this fashion, women wore veritable mountains of gauze, ribbons and various ornaments. These hairstyles, whose excessiveness sometimes bordered on the absurd, became a favourite target of caricaturists.”

The French were at war with Britain throughout much of the 18th century and this was often reflected in court fashion. After the “Belle Poule” warship was victorious in a battle against the Brits in 1778, Marie-Antionette appeared at a ball with a model of the said frigate atop her head, her hair powdered and sculpted to imitate a stormy sea. The look was an instant hit and other noble courtiers began referencing the political climate in their statement wigs, adorning giant hairpieces with bird cages or other ostentatious conversation pieces. Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire and close friend of the French queen (despite their naval and military differences), also fond of a boat or two in her barnet, was noted as sporting an entire pastoral scene, including miniature wooden sheep, upon her pouf. In fact, the Duchess’s wigs were so coveted that ‘Devonshire Hair Powder’ became a ‘must have’ for the social elite.

By the end of the 18th century, powdered perukes, already condemned as “Bushes of Vanity” by American pilgrims a century earlier, had come to represent all that was corrupt in the French court. Riots eventually culminated in the French Revolution, during which those aristocratic heads that had borne the wig so proudly, were literally severed from their bodies. The bourgeoisie, who replaced them, favoured more paired-down, natural fashions, including displaying the hair with which they were naturally blessed, in line with their principles of ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’. Instead, guillotine necklaces (fine red chokers tied about the neck) and closely cropped hair became all the rage, their symbolism wasted on no-one. Stepping outside looking too decadent, too rich or out of step with the common man was officially out of fashion. Parallel to this came the wig powder tax, imposed by the British Prime Minister William Pitt in 1795, that proved to be the final nail in this dying trend’s coffin. Described as ‘infested, dusty and tangled’, the wigs that remained in the aftermath were, according to the National Museum ‘associated with an aristocracy opposed to reforms and a bygone era’ and, like their wearers, were laid to rest.