Self-styled Scottish ‘doctor’ James Graham may not have been the original snake oil salesman but he wasn’t far from it. The ultimate eccentric showman who spotted innumerable untapped business opportunities in the sex industry, James Graham gleefully administered a cocktail of somewhat questionable, shall we say, ‘fertility treatments’ to his well-to-do aristocratic patients, who were under pressure to produce an heir. In fact , he not only promised ecstasy but also fertility thanks to a sensational electro-magnetic “Celestial Bed” that awaited patients inside his 18th century sex clinic. An added bonus for the lucky patient would be that all this magical mojo happened under the keen eye of the good doctor. Not only was James Graham a voyeur, mentor and guide through these intimate sessions, he was also an ‘educator’, giving graphic lectures on the health benefits of electrocuting people’s nether regions during sex. James Graham was once regarded as a quack, but in hindsight, was probably the world’s first true sex therapist. So let’s jump in the time machine and book an appointment.

The son of a humble saddler from Edinburgh’s industrious Grassmarket neighbourhood, James Graham (1745 – 1794) had grand ambitions of becoming a medical doctor. He enrolled at Edinburgh University’s prestigious Medical School, only to drop out and set up his own apothecary in Doncaster where he began calling himself a doctor. He married a Mary Pickering and they went on to produce three children, but a restless Graham left England in 1770 for the USA and stopped in Philadelphia to practice cataract surgery having developed an interest in eye and ear issues. It’s in America that his fascination with electricity, which would play a key role in his later ‘treatments’, was first sparked by Ebenezer Kinnersley, a close friend of Benjamin Franklin. If Franklin’s stormy night kite could draw an electrical charge, what might this new found stimulant be used for? It was also around this time that Graham started to conjure up the most famous of his inventions, the ‘sexsational’ Celestial Bed. When the American Revolution was about to kick off, he hastily returned to England where he set up shop in Bath.

By now a total convert to the extraordinary properties of electricity, he advertised in the papers, promised cures by electrocution to just about any imaginable affliction. Even Georgina Cavendish, the famous Duchess of Devonshire heeded the love doctor’s call, arriving at his temple disguised in a veil but at least two other celebrities of the day, historian Catherine Macaulay and politician Horace Walpole publicly endorsed Graham’s ‘cure’. A triumphant James Graham returned to his earlier imaginings of a celestial bed that could literally put the spark back into matrimonial relations.

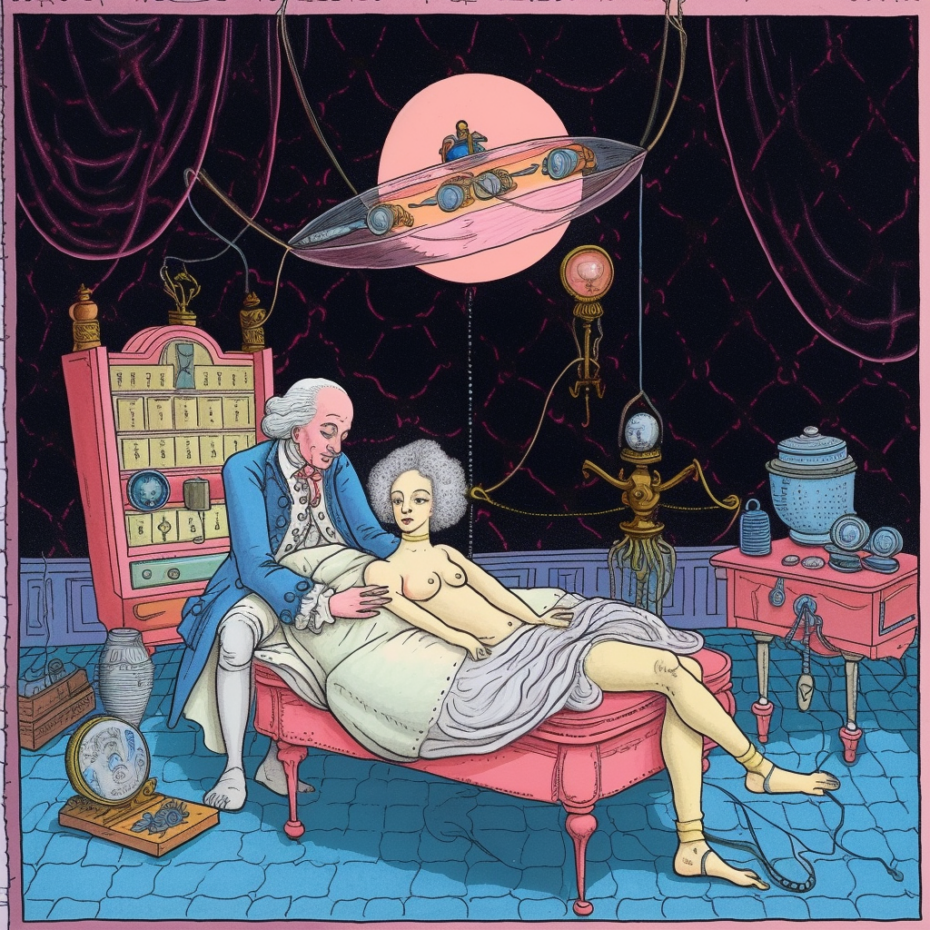

He implemented his dream contraption dubbed the ‘Temple of Health’ in the Adelphi Buildings in the City of Westminster in 1780, exhibiting electro-magnetic devices and treating his patients with electricity, magnetic therapy, pneumatic chemistry and music therapy. He also had on sale all sorts of potions such as ‘Electrical Aether’ and ‘Nervous Aetherial Balsam’, and gave lectures on medicines and even published marriage guidance. His assistants were beautiful models – the exquisite English model Lady Emma Hamilton, for example, was employed as his assistant / Greek goddess, Hebe Vestina.

Let’s pause for a moment and imagine being a visitor to the ‘Temple’ … You’d be received and lured seductively through a set of luxuriously decorated rooms by one of James Graham’s hand-picked, scantily-clad sirens, a ‘Goddess of Health’ via shelves of the doctor’s potions and lotions, tinctures and tonics all ready to be purchased and applied – and of course you’d constantly be reminded of the ultimate temptation … the libido-amplifying shocks on offer.

Meanwhile, James Graham would also boost his enterprise by giving graphic sex education lectures to a paying audience, blaspheming the likes of masturbation and prostitution. Sex and procreation were seen as a national duty and treated with practical advice. For example, washing the genitals with cold water after sex was a recommendation. At the end of a lecture, audience members were invited to put theory into practice with a free electric shock ‘taster’ via a metal conductor attached to their seat. Free marriage guidance was also offered in a pamphlet titled “A Private Advice’.

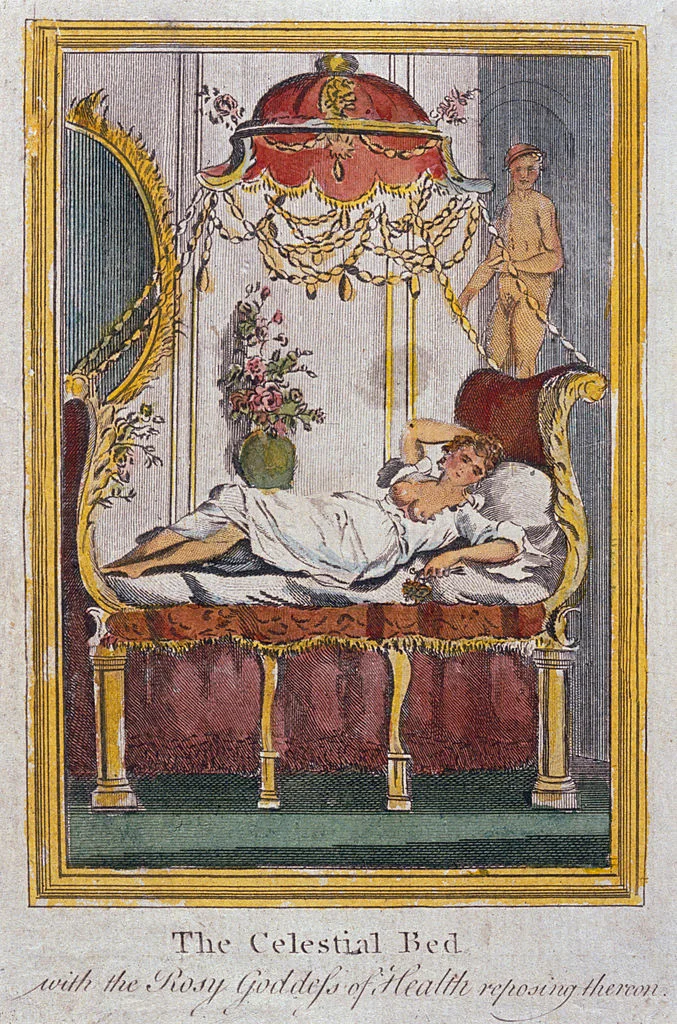

So successful was Graham’s Temple of Health – enhanced by his blatant self-promotion – that he opened a twin temple in London’s Pall Mall in 1781 called the ‘Temple of Hymen’ where he finally got to implement his ultimate fantasy installation, the ‘Celestial Bed’. And here is where Dr Graham’s sex education was properly put into practice: couples would pay a substantial sum to copulate under supervision (and no doubt guidance) in the temple’s inner shrine, with the doctor virtually breathing down their necks. For clients pressed to produce offspring, Graham (and his contraption) claimed to guarantee absolute success.

On his 12 by 9 ft love-bed that crackled with electric currents and came complete with mirrors overhead, valiant couples would attempt to perform, aided by aphrodisiacs like rose leaves, balm, lavender and horse hair from virile stallions no less, embedded in the mattress.

The bed could tilt for optimum efficacy. ‘Naughty’ illustrations would serve to get the couple in the mood, reservoirs beneath the bed filled with exotic oils and heady scents would further encourage amorous activity, while fresh flowers and a couple of live turtledoves in a cage were thrown in for good measure too. At the head of the bed, above a moving clockwork image celebrating Hymen, the god of marriage, it read “Be fruitful, multiply and replenish the earth” – presumably just in case the couple lost incentive or focus. Graham boasted that the electric coils around the couple provided ‘magnetic fluid’ for their strength, perseverance and fertility. Forty glass pillars insulated the magnetic electrified contraption whilst organ pipes spouted music synchronised with the climactic nature of the labour of love.

But alas, all good things come to an end, and by 1773 Graham and his temples of temptation had fallen out of favour. He was being ridiculed by the papers and suffering severe financial difficulties. Just about bankrupt, he retreated to Edinburgh, where he attempted to erect yet another Temple of Health on the city’s posh South Bridge. However, the conservative magistrates would have none of his debaucherous dealings on their patch and banned Graham’s unseemly propaganda. Graham retaliated by publishing a pamphlet condemning the magistrates for their censorship of free speech. A court case ensued, Graham lost, was fined £20 and jailed to boot.

Desperate times called for desperate measures and Graham’s next hair-brain scheme, coined ‘earth bathing’, saw him lecturing the great and the good of Edinburgh whilst he was buried up to the neck in soil, hailing its medicinal properties. However, as hard as he was peddling this, earth bathing simply didn’t catch on and by the 1770s, Graham’s own mental health had begun deteriorating. He was incarcerated on many occasions, having once while found wandering naked after giving his clothes to the poor.

Ever the hustler, in the mid 1780s, he finally tried his hand at the business of religion and set up the New Jerusalem Church, of which he was the sole member. Still unable able to resist outlandish and experimental gimmicks, he subjected himself to extended periods of fasting to prolong his life. He was also an practitioner of sleeping in the nude, with no covers and all windows wide open. In trying to prove his own theories, he died emaciated at the age of 49 – and hopefully found his own celestial bed at last. He was buried at the mysterious Greyfriar’s Churchyard in Edinburgh.

James Graham prolifically published his ideas throughout his life. His was the age of enlightenment, a time when alternative thought was celebrated, before the confining sensibilities of the Victorians took hold. Although his written works were characterised by a showman’s florid and exaggerated narrative, he also expressed surprisingly progressive and forward-thinking views on issues such as slavery, women’s education, diet (he was devout vegetarian) and pioneered safer sex lightyears before everyone else. Similarly, his belief in the physical and mental healing power of music, art and aroma therapy was so ahead of its time. One may well see James Graham as a loony opportunist, but there’s no doubt that he opened a door for modern day conversations about sex.