Known as ‘The City of Light’ for nearly two centuries, Paris led the way during the Age of Enlightenment, and yet history has forgotten one of the most bizarre and beautiful uses of light ever witnessed by Parisian society: electric jewellery. During the Belle Epoque, the chicest Parisian parties were lit up with electrified fashion accessories created by an unsung genius of Parisian innovation. As Scientific American reported in 1879 “Among the specialties for which the French are noted there is nothing more curious than electric jewellery.”

These bejewelled works of wearable art were the brainchild of Gustave Trouvé, an electric pioneer whose quiet, artistic nature kept him out of the spotlight and thus out of the history books. While inventor superstars like Nicholas Tesla and Thomas Edison put on grandiose spectacles featuring elephant electrocution and indoor lightning, Trouvé’s electrical world focused on the infinitely small.

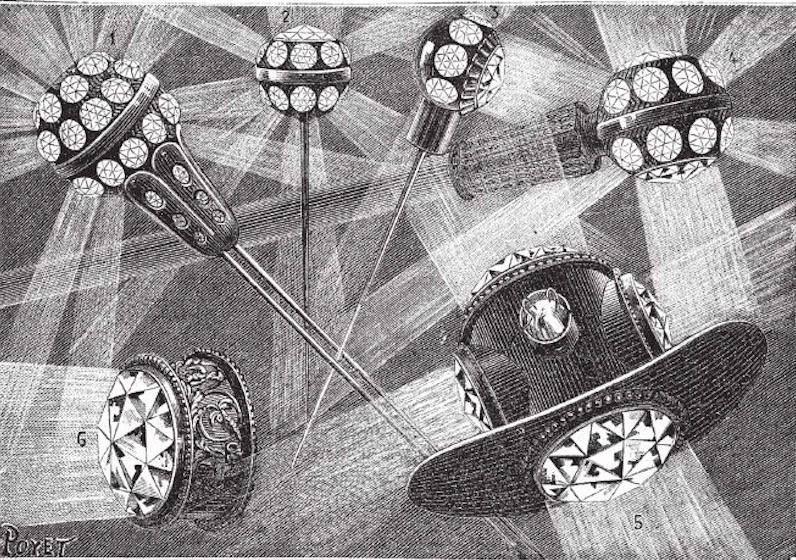

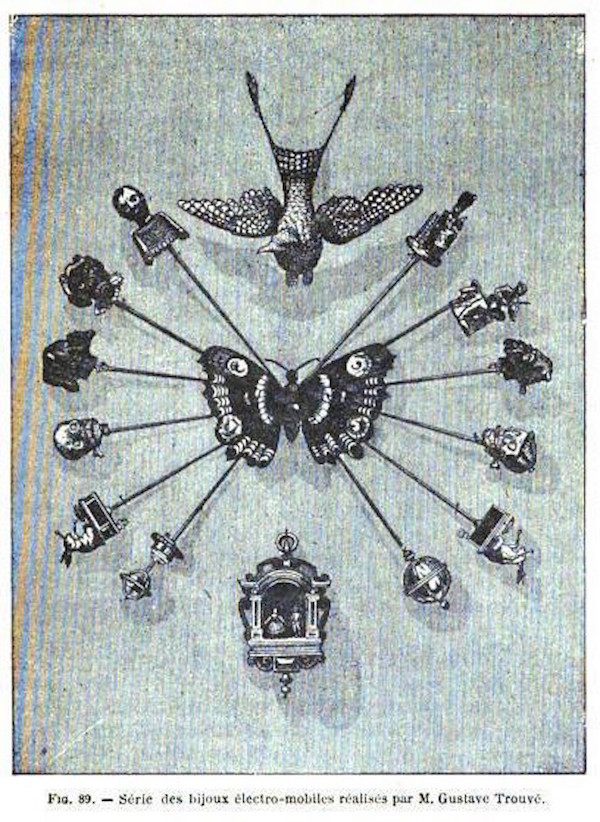

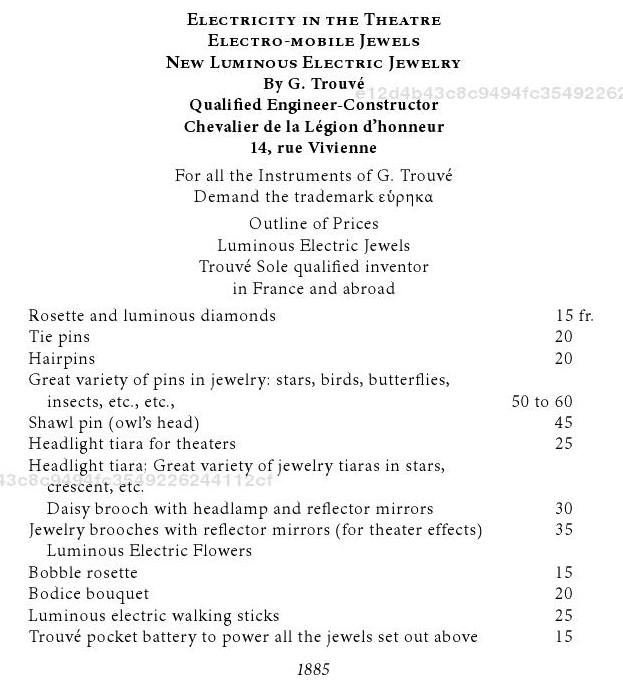

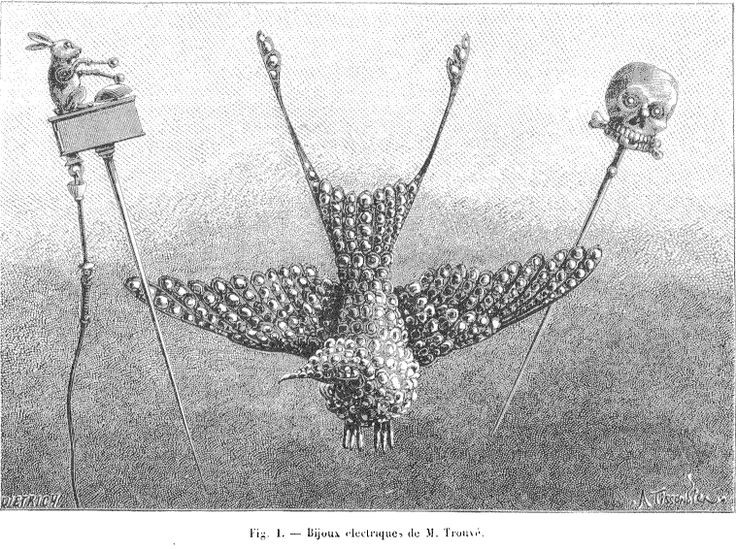

Originally a watchmaker, Trouvé invented the ‘Lilliputian battery’ (known today as the AA) to animate “jewellery, clockwork and other objects d’art.” This battery could be discreetly tucked away in a gentleman’s pocket or lady’s coiffure creating the illusion that the accessories sprung to life on their own. Animations included: a skull on top of a tie pin whose jaw would chatter when switched on, a bejewelled butterfly hair accessory with fluttering wings, a brooch that featured dancing ballerinas on a tiny golden stage, glass flower corsages that would light up etc…Tragically, the vast majority of Trouvé’s bijoux electriques were destroyed when in 1980 the building that contained all of his archives burned to the ground. Today, only one skull tie pin remains at the Victorian and Albert Museum in London. A video of the skull in action can be found here or below.

A brochure produced in 1885 by Trouvé translated and reproduced by Kevin Desmond in his excellent study of the inventor Gustave Trouvé: French Electrical Genius 1839-1902. By 1891 these pieces had become so rare and sought after that the prices shot up to upwards of ten times the original cost.

Trouvé’s bijoux electriques made their high society debut in 1879 at the fiftieth anniversary celebration of the Ecole Centrale des Arts et Metiers at the Hotel Continental in Paris. A journalist from La Nature that attended the lavish event reported:

“Some of the guests are wearing Trouvé’s charming electric jewels: a death’s head tie-pin; a rabbit drummer tie-pin. Suppose you are carrying one of these jewels below your chin. Whenever someone takes a look at it, you discreetly slip your hand into the pocket of your waistcoat, tip the tiny battery to horizontal and immediately the death’s head rolls its glittering eyes and grinds its teeth. The rabbit starts working like the timpanist at the opera. The key piece, a bird, was a rich, animated set of diamonds, belonging to Princess Pauline de Metternich, the famous Vienna and Paris socialite and close friend of the Empress Eugénie. […] Carrying it in her hair, the princess could at will make the wings of her diamond bird flap.”

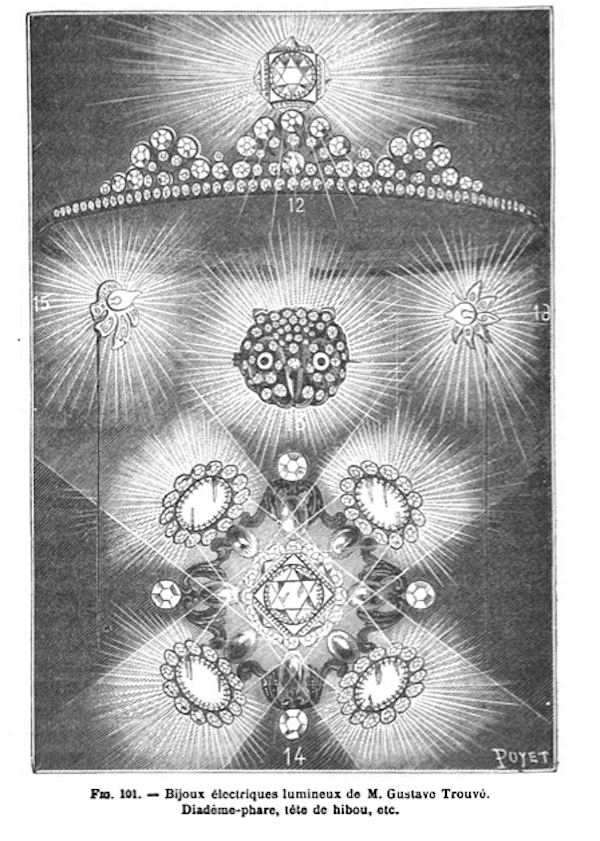

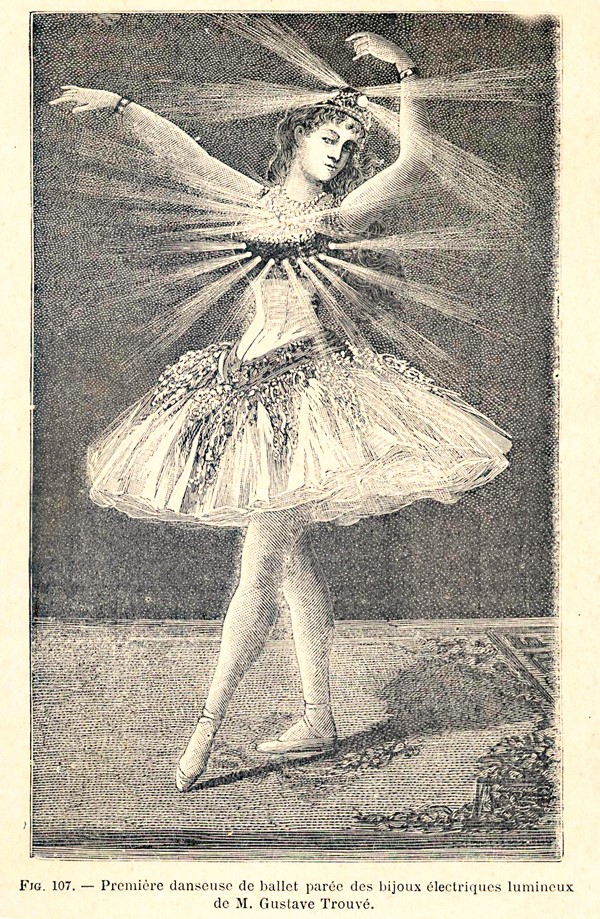

Though fairly successful as playthings for the rich and elite, Trouvé’s electric jewels truly ‘shone’ at the theatre. In 1884 The Folies Bergère commissioned Trouvé to create luminescent accessories for the costumes in their Le Ballet des Fleurs. Audiences were dazzled when twenty beautiful young women, each representing a different flower, gracefully danced onto the stage wearing illuminated multicoloured crowns with matching broaches.

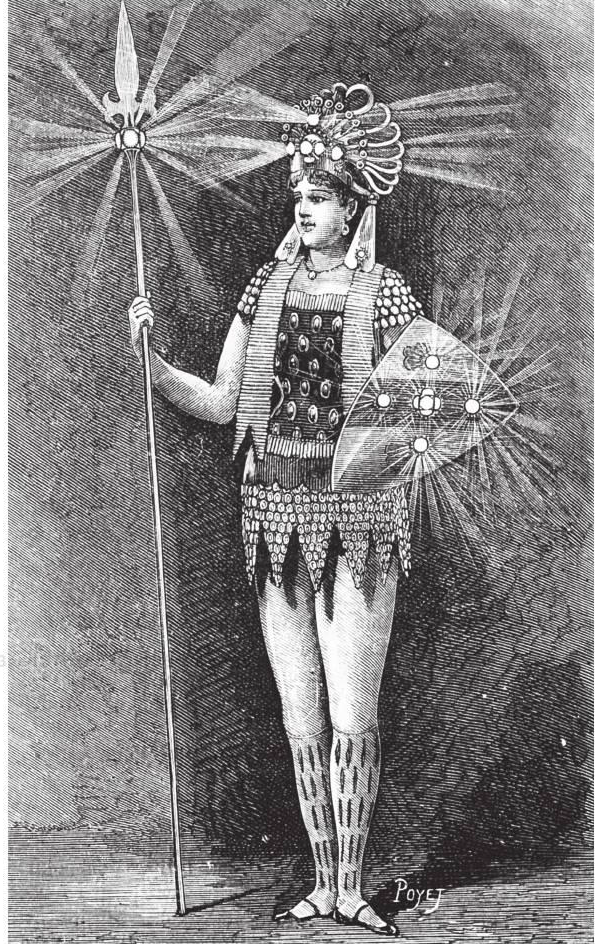

At about the same time in England, Trouvé provided the spectacular electric effects for The Empire Theater’s Chilpéperic: Grand Music Spectacle, in Three Acts and Seven Tableaux. In the final act, 50 Amazon women adorned with helmets, shields, and spears, rushed onto the stage. They were divided into four corps: the Diamond corps, the Ruby corps, the Emerald Corps, and the Topaz corps. Suddenly, in the midst of their complex routine the glittering jewels on their armour lit up: four on the helmet, five on the shield, and one on the spear. The audience, who had never witnessed anything like it, erupted into a deafening applause. Among the enthusiastic spectators was a young little-known Irish playwright named Oscar Wilde.

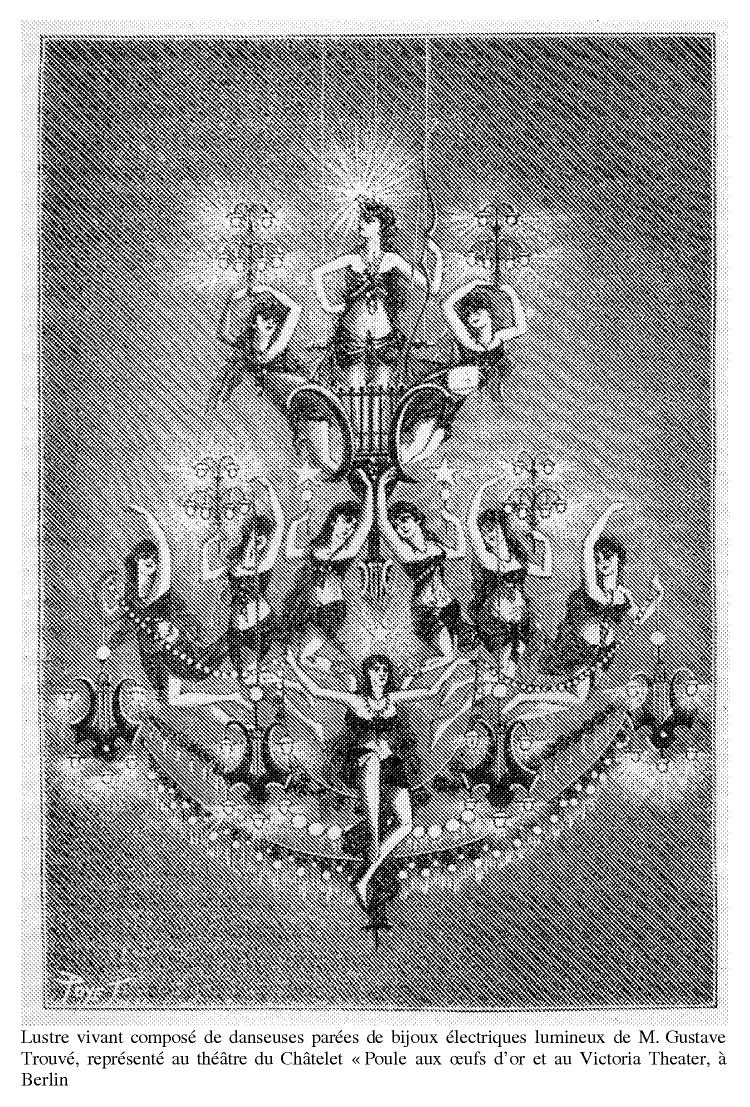

Back in Paris at the Chatelet Theatre, a gigantic human chandelier, illuminated by scantily-clad women decked out in electric jewels, descended above the audience for the ballet La Poule aux oeufs d’or (The Hen with Golden Eggs).

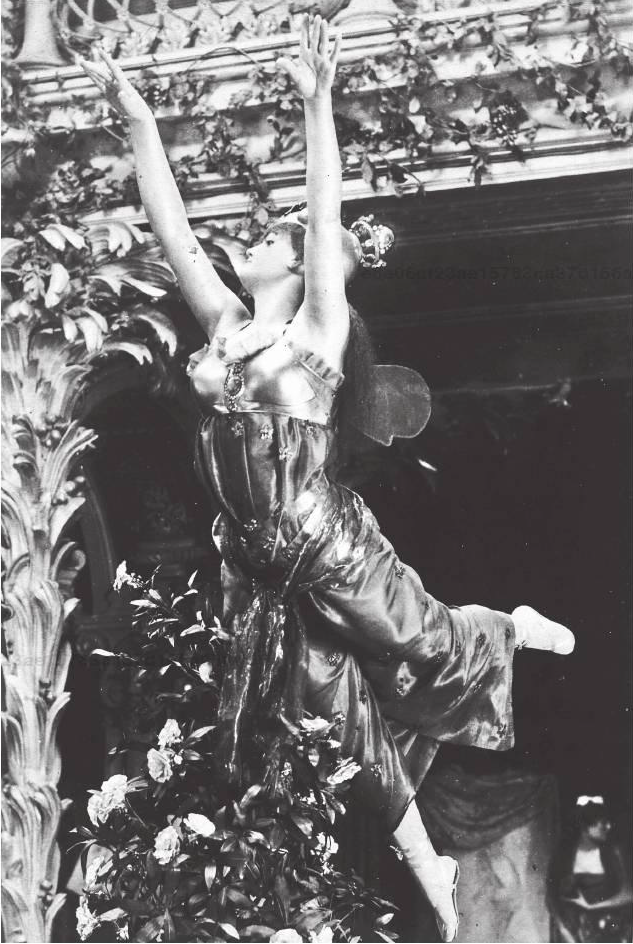

If you couldn’t afford to buy Trouvé’s bijoux or a ticket to the theatre, you could still enjoy his creations at the popular waxworks museum, le Musée Grevin, which added the inventor’s electric jewels to an exhibition in 1884. Trouvé installed a life-size wax model of a dancing fairy wearing an electric crown. He suspended her above an enchanted garden glimmering with garlands and bouquets of luminous glass flowers.

From Gustave Trouvé: French Electrical Genius 1839-1902

At the time, a young Georges Méliès was working at the museum as a magician and was particularly impressed by Trouvé’s electric spectacle. Years later he would become a pioneer in special effects as a silent film director, but it was perhaps back at the waxworks museum that he was first inspired to create those fantastic on-screen worlds thanks to Trouvé’s luminous wonderland.

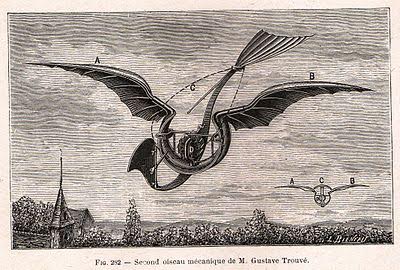

Gustave Trouvé s electric jewellery, seen today as the first wearable technology, represent only a small fraction of his achievements. The electric boat, car headlights, underwater lamps, oxygen spacesuits (at the time for balloonists), and a wide array of electrical medical instruments are among his many inventions. Perhaps his most impressive creations were his mechanical birds which, along with being the stuff of every steampunk lover’s dreams, were some of the world’s first successful flying apparatuses.

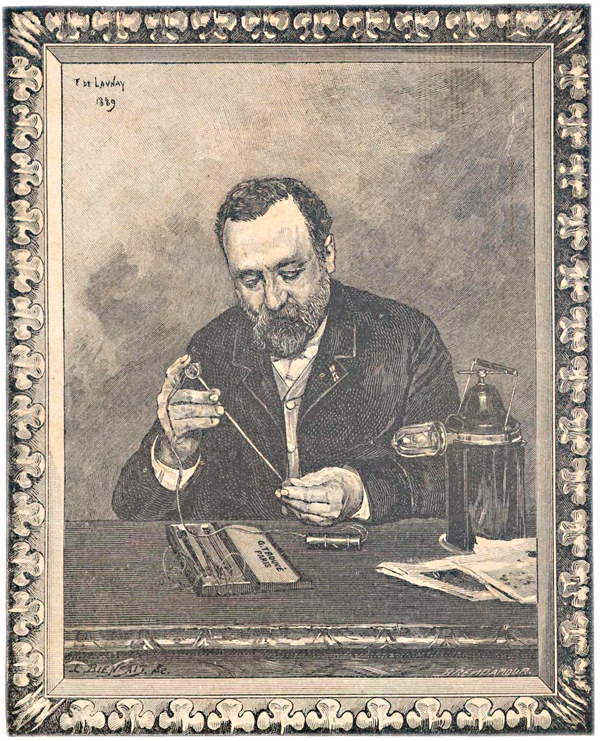

One of the few existing lithographs of Trouvé. No photographs of the inventor have survived.

For over a century after his death, Trouvé remained an obscure and tragically forgotten figure. Even before the fire that destroyed his legacy, this prolific inventor was conspicuously missing from all major encyclopedias and archives. In fact, the lack of information on Trouvé is so complete that some historians wonder whether some rival deliberately went about erasing him from history.

Today, thanks to the exhaustive work of one researcher named Kevin Desmond, Gustave Trouvé is finally beginning to receive the recognition he deserves. In 2012 the Mairie du 2ème erected a plaque outside of 14 rue Vivienne where he lived and worked for 25 years. Though a small gesture compared with the statues and museums dedicated to the likes of Edison, it is a definitive step towards honoring the man who lit up the City of Light.