I say “Pop Art”, you say Andy Warhol … or maybe Roy Lichtenstein. Pop is often seen as a quintessentially mid-century American (and male) movement, a reaction to overconsumption and popular images encapsulated by Warhol’s soup cans. But Pop Art actually dates back to artists working in 1950s London, one of whom was the co-founder and mother of British Pop Art, Pauline Boty. Also known as “The Wimbledon Bardot”, she played a major role in the definition of the Pop aesthetic. But because of her premature death, as well as a tradition of sidelining female artists, Boty is not as well-known today as many of her contemporaries. Despite a posthumous “rediscovery” and a renewed interest in her work in the 1990s, several of her most famous works remain missing to this day.

Pauline Boty was born in 1938 in South London. She was raised alongside three brothers in a male-dominated, middle-class, Catholic household. Her traditional upbringing became the root of her rebellious, feminist style. Boty fell in love with art as a girl and was accepted to the Wimbledon School of Art at the age of 16. But her father refused to support her ambitions. Thankfully, her mother stepped in and encouraged her daughter to go to Wimbledon. She had also harboured dreams to go to art school, but had been forbidden by her parents.

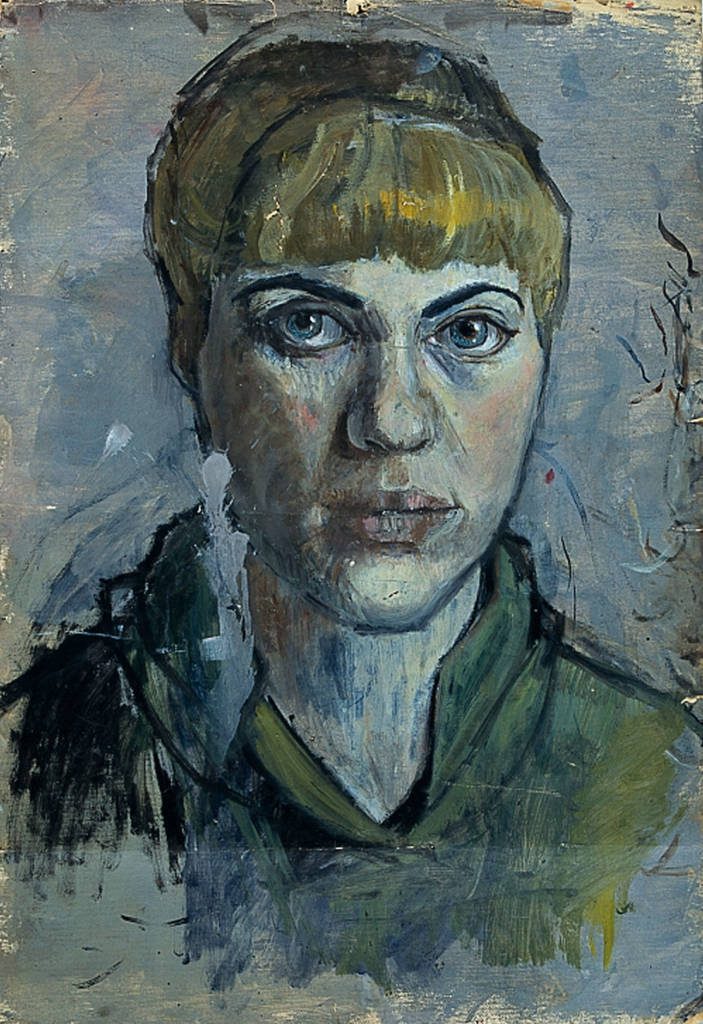

At Wimbledon, Boty received a traditional artistic training. She stood out as one of the strongest students and became interested in collage as a medium. Boty would have preferred to study painting, but was pushed to concentrate in stained-glass. This was part of a larger trend for female art students to be pushed towards “craft” mediums like fibre arts and pottery, and away from more celebrated mediums like painting and sculpture. While Boty received numerous honours for her work in stained-glass, she continued to paint during her free-time .

The sixties in London were an exciting time to be a student and Boty threw herself into numerous activities, from theatre to poetry to a group that protested ugly modern English architecture.

Boty ran in the same circles as David Hockney, Peter Blake, and Peter Phillips. She became a fixture of Swinging London, and her collages and paintings were featured in many group exhibitions, including the first Pop Art exhibition in 1961 at the A.I.A. Gallery in London. She also began appearing in theatre and television productions. She contributed to the BBC radio program “The Public Ear” and would often speak about the systemic oppression of women in modern life (she also interviewed the Beatles!). Transcripts of the program are difficult to find today, but here’s one of the more well-known quotes from a 1963 broadcast:

“A revolution is on the way, and it’s partly because we no longer take our standards from the tweedy top. All over the country young girls are starting, shouting and shaking, and if they terrify you, they mean to, and they are beginning to impress the world.”

Pauline Boty

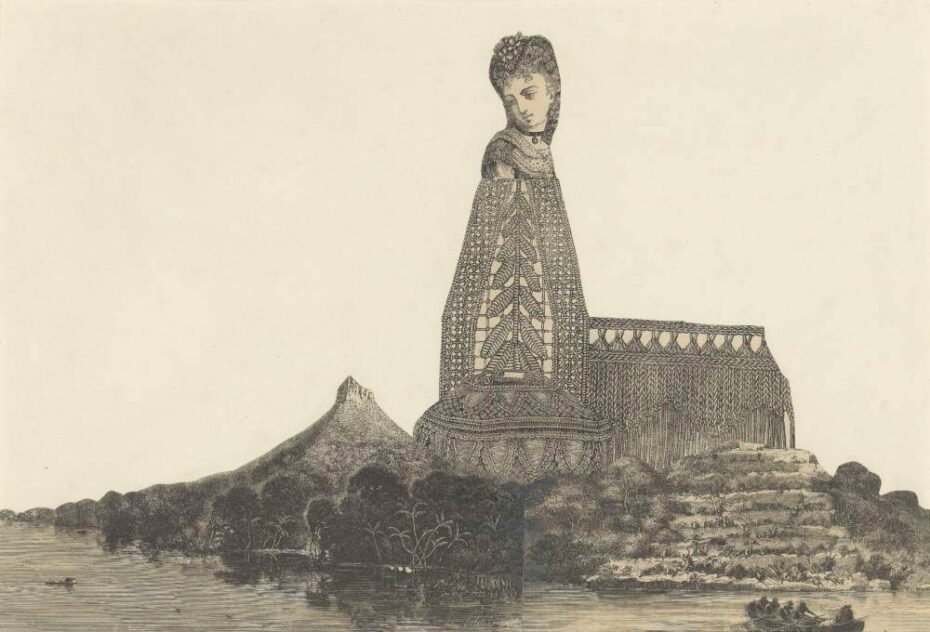

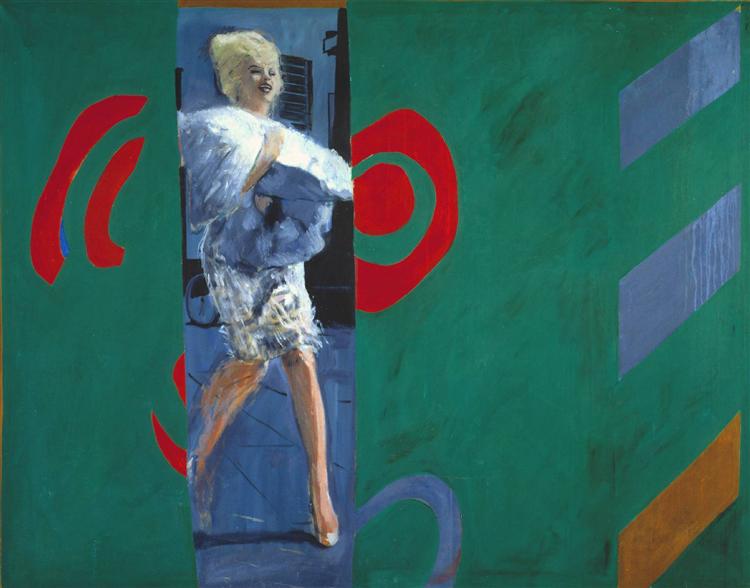

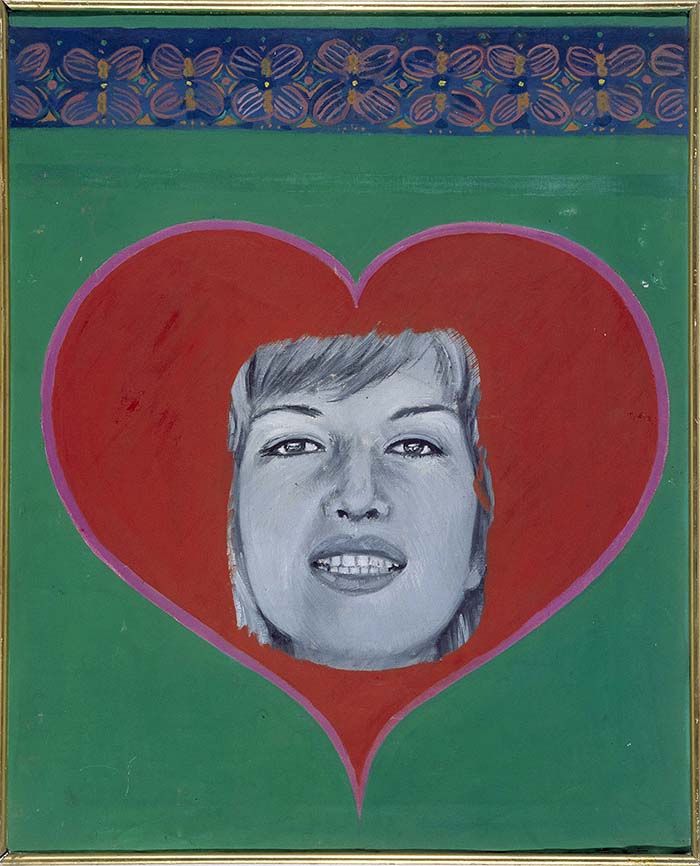

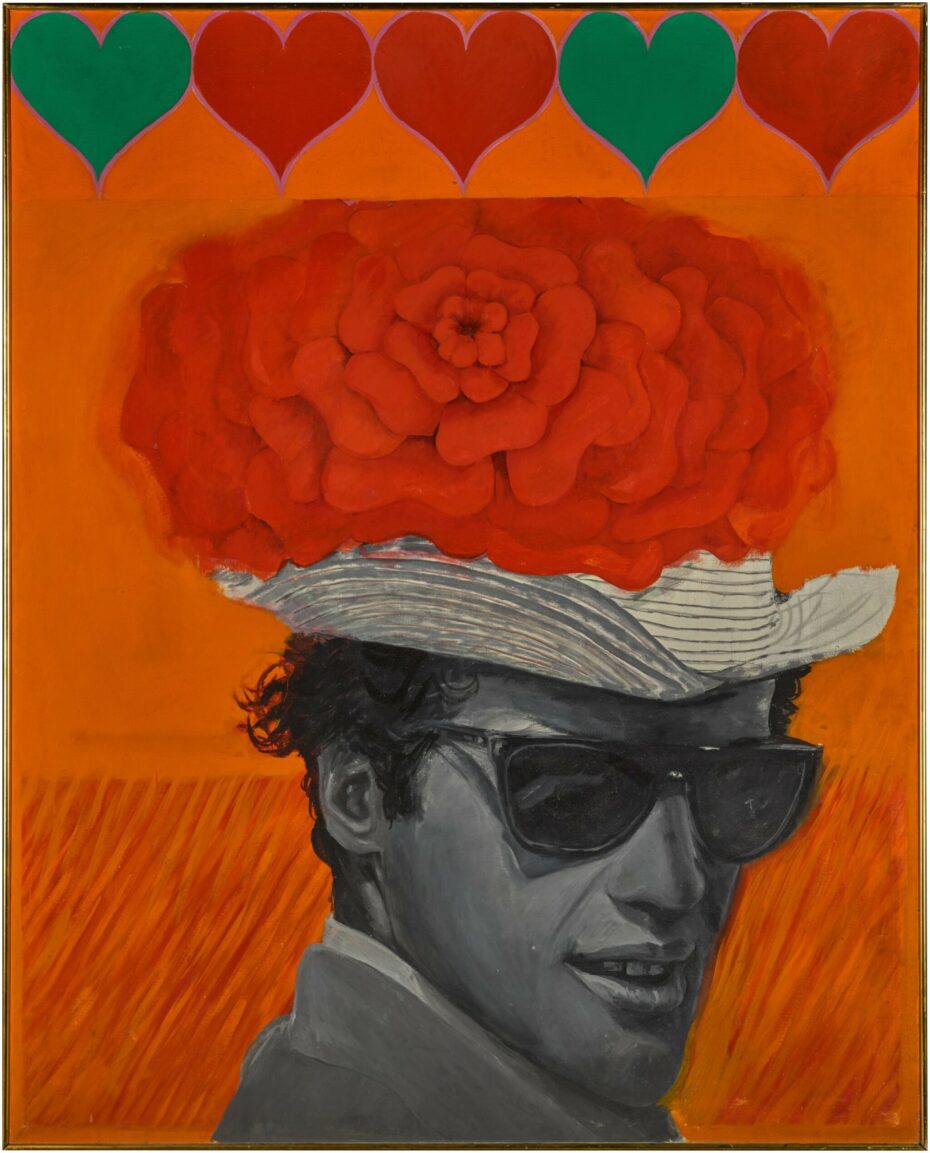

Boty’s artistic style is playful and striking. She used images pulled from newspapers, movies, or books, often combining what is regarded as “high culture” with elements of popular culture such as movie stars or advertisements. She painted female- and more controversially- male celebrities as sex symbols.

Yet despite the seemingly liberal values of 1960s London, Boty was often dismissed due to her gender. Scene magazine summarized the sexist public perception of Boty in their cover story on the artist: “Actresses often have tiny brains. Painters often have large beards. Imagine a brainy actress who is also a painter and also a blonde, and you have Pauline Boty.” Critics, artists, and the media were often uncomfortable with the unapologetic sexuality of Boty’s work. She described the rapport between sex and art in a conversation with Nell Dunn (in her fabulous Talking to Women):

“It’s to do with everything … can be as varied as being alive is varied … one of the most terrifying things about the puritanism that still exists in England today is that people are guilty about sex.”

Boty was also passionate about acting, but was often typecast, playing the same bombshells and heartbreakers over and over. This frustration is perhaps one of the reasons that Boty chose to paint Marilyn Monroe. Her empathetic painting The Only Blonde in the World suggests that Boty felt a certain kinship with the American actress.

We spoke to Christopher Gregory, who runs the excellent Paulineboty.org, and he pointed out that Boty found Monroe as a subject before Andy Warhol, just another testament to her influence and role as a leader of the Pop movement.

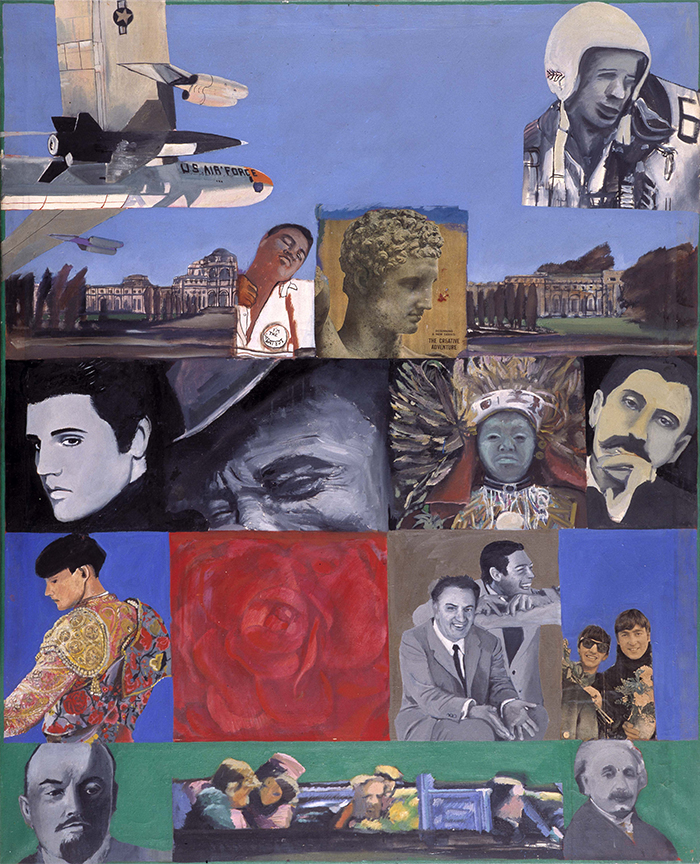

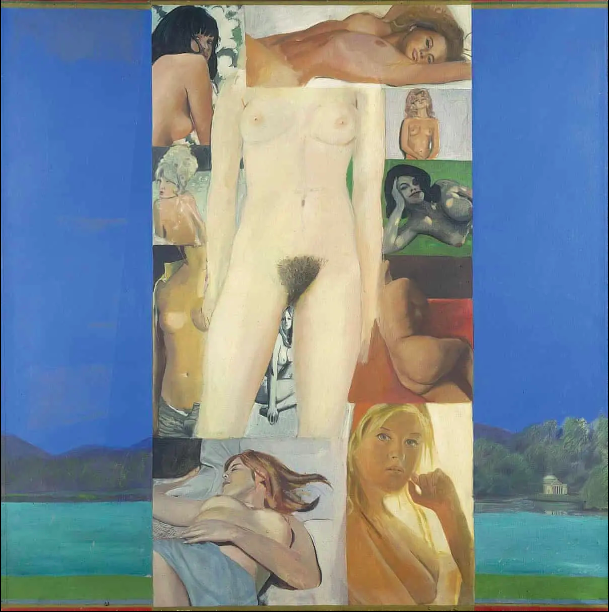

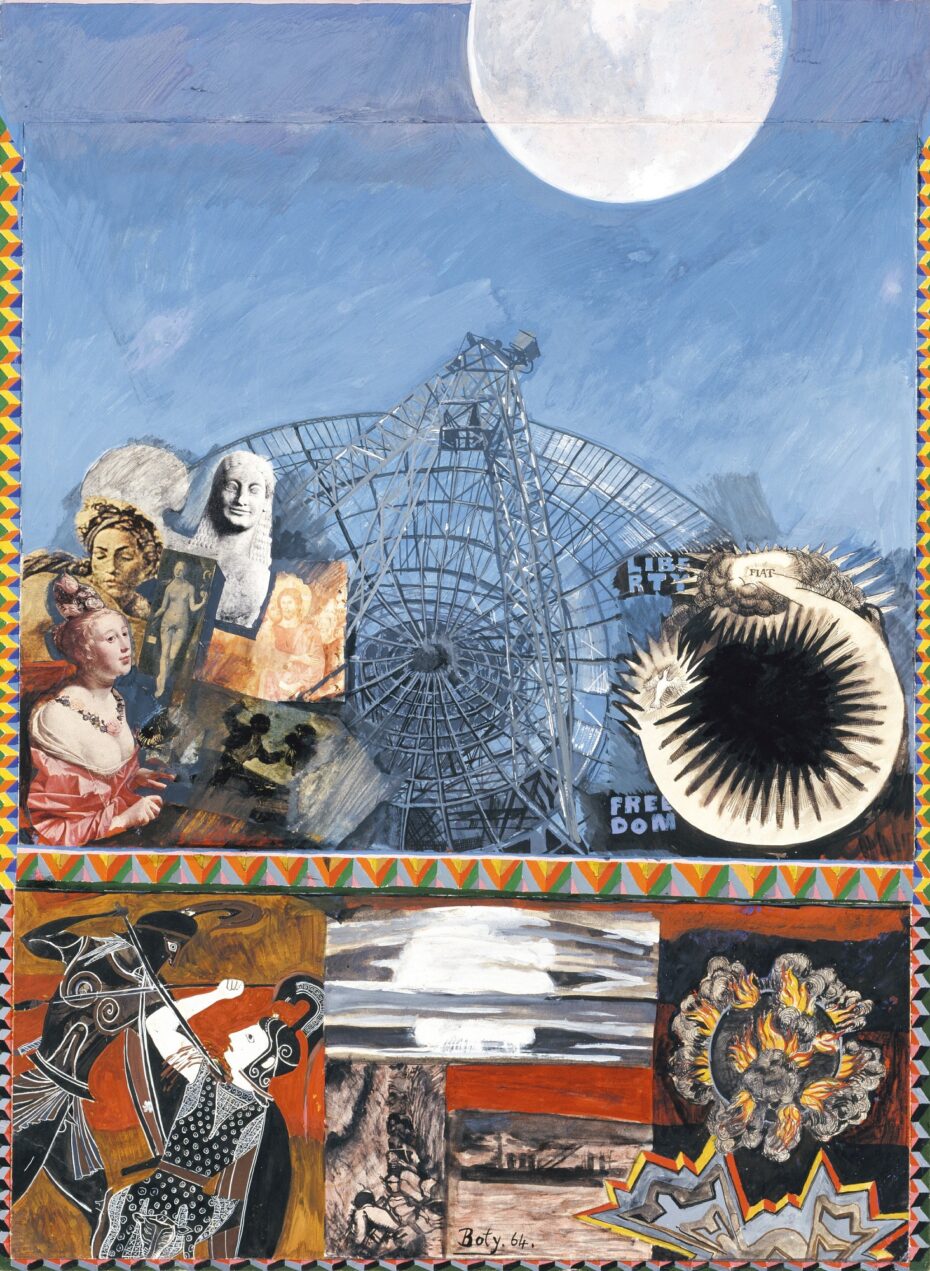

Boty’s work addressed the sexism she experienced every day, most strikingly in her series It’s a Man’s World. The first painting depicts a variety of figures, from Vladimir Lenin to Elvis Presley to Marcel Proust. The collage reinvents the tradition of the group portrait and underlines the violence and tragedy of this man’s world. The Kennedy assassination is depicted, as well as an American fighter jet. In its companion piece, another collage depicts only women, but they are all nude, presented in a hyper-sexualised way that references the male gaze.

While the men in the series are nearly all individuals, known for their accomplishments, the women are anonymous and objectified. The works also testify to Boty’s rich visual vocabulary, referential style, and interest in merging high and low subject matter.

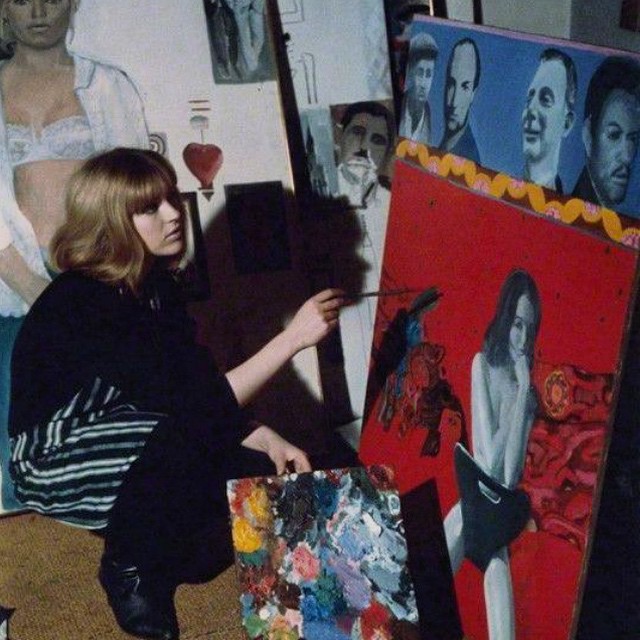

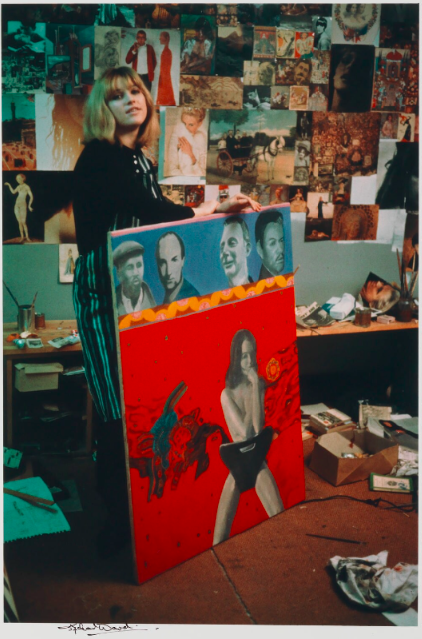

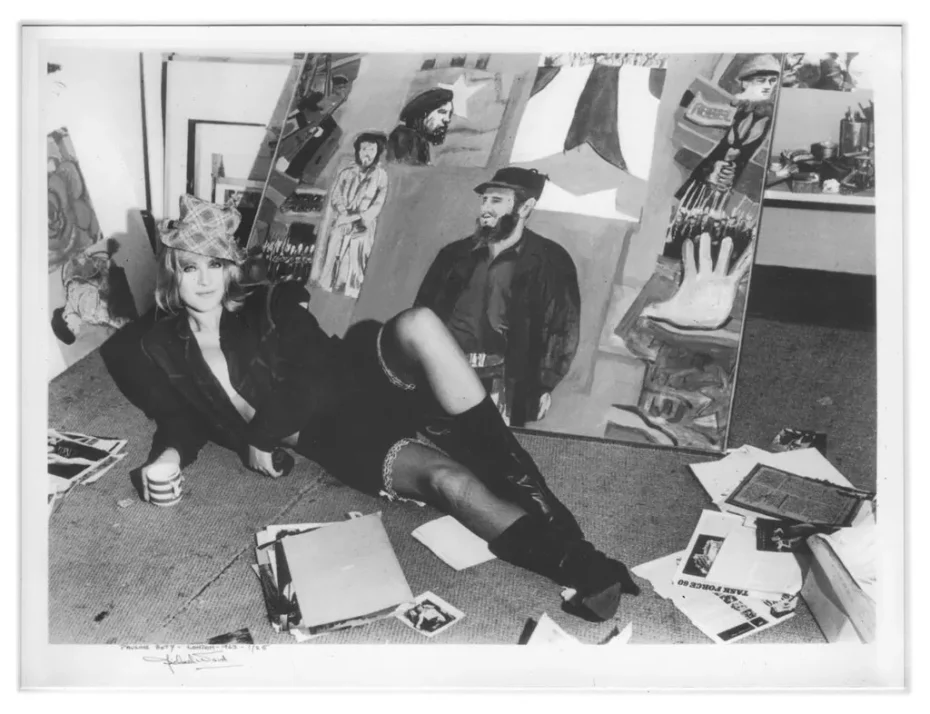

In 1963 Boty’s first solo show was held at Grabowski Gallery in London. It was met with widespread critical approval. The same year she met the literary agent Clive Goodwin. They married after a ten-day courtship and became a power couple of London’s artistic scene. Boty continued to work and paint, most notably finishing the piece Scandal ’63 (seen in this photo by Michael Ward).

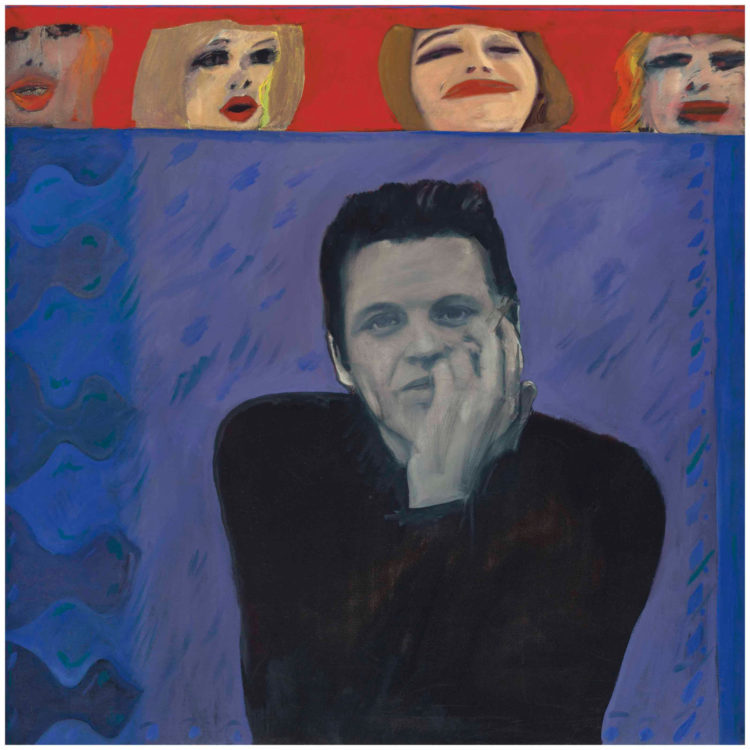

The large painting depicted those involved in the Profumo affair, a major event in 1960s British politics. In the foreground is Christine Keeler, the 19-year-old model who had an affair with John Profumo, the Secretary of State for War in the Conservative government (he’s pictured at the top of the work with other government figures). By pulling her subjects directly from current events, Boty ,ade an important contribution to the still developing Pop sensibility. She also chose to centre the story on Keeler, unlike much of the media coverage of the time.

Boty became pregnant in 1965, but found out soon after that she had cancer. In order to protect the fetus, she did not undergo chemotherapy. She died five months after giving birth in 1996. She was 28. Her daughter Boty Goodwin tragically overdosed and died at the age of 29.

Largely forgotten by art history and lacking any heirs, Boty’s work languished in a barn owned by her brother for decades. After her death she was remembered largely for her looks and relationships with men, not her work. (Like the theory that Bob Dylan wrote the song “Liverpool Gal” about her).

But she was not destined to stay in obscurity forever. Recent changes in art history as well as the passion of one curator led to Boty’s rediscovery. Since Linda Nochlin’s essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” kickstarted the feminist art history movement in 1971, critics and historians had been reevaluating the Western Canon with special attention paid to artists who were excluded from it. It was time to take another look at Boty’s work and her treatment by the artistic establishment.

In 1990, the curator David Alan Mellor uncovered Boty’s work in her brother’s barn. Mellor restored the pieces and organized an exhibition at the Barbican in 1993. It was the beginning of her long overdue comeback.

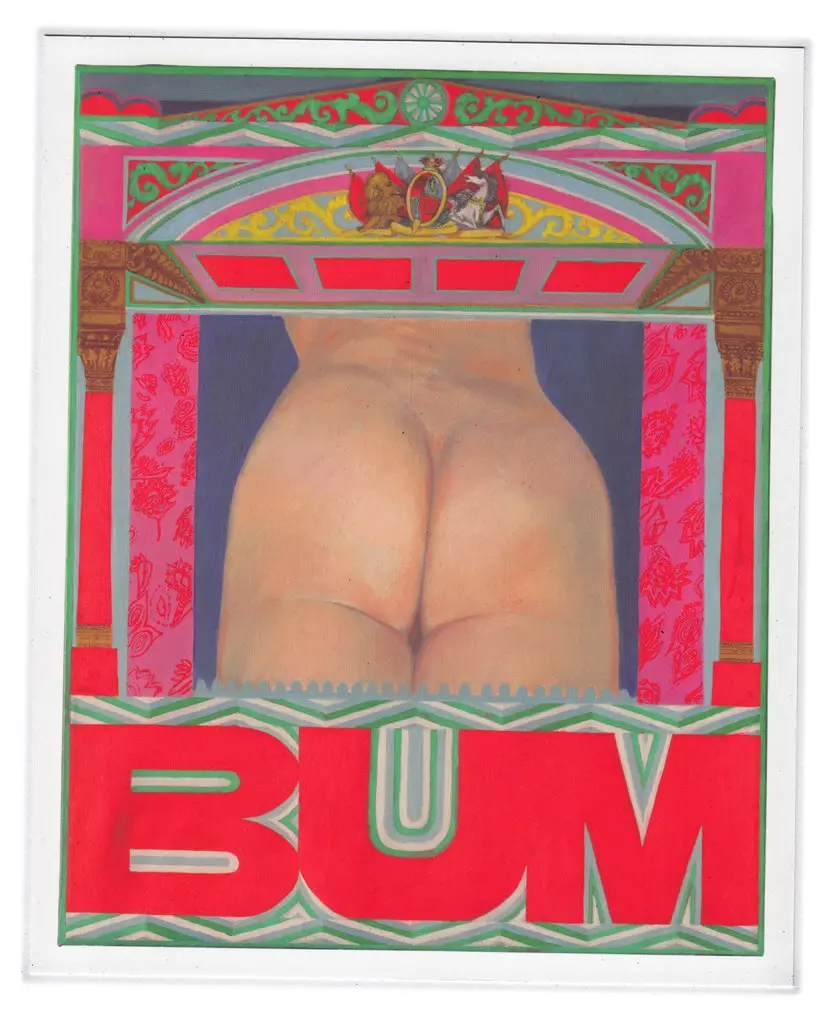

In 2013 the Wolverhampton Art Gallery held the first major exhibition on Boty since her death, curated by Sue Tate, who has also written a book on the artist. Bum, the last work Boty is known to have completed, broke the artist’s auction record, which was shattered again last year with the sale of With Love to Jean-Paul Belmondo by Sotheby’s London. In 2016, the Scottish writer Ali Smith centered her novel Autumn on Boty. A new generation fell in love with her work. Little by little Boty was once again becoming a fixture of the cultural conversation.

Now comes the mystery. At least two of Boty’s major works remain missing, including Scandal ’63, July 26, as well as an another untitled painting. According to Christopher Gregory, there has been an effort in the past decades to find these works, but interest has been renewed in the last few years after the writer Tom Glover became determined to track them down, especially Scandal ’63. He found that the painting had in fact been commissioned, and therefore likely still exists in private hands somewhere. But where? He found a connection with the art dealer Mateusz Grabowski, which led him to discover the name of the secretive buyer: Wright. That’s where Glover hit a dead end, leading him to write this appeal to anyone who might have any leads.

In order to tell women artist’s stories, we need their work. As Gregory tells us, new information on Boty keeps cropping up, due to the dedicated amateur and professional researchers, art historians, and history sleuths that have been on the case. Which could include you! Check your attic, the next flea market you visit, and perhaps one day we can track down these feminist Pop masterpieces.

Here’s a map of the known locations of Boty’s works.