There isn’t one clear inventor of electronic music, although if you start looking, you’ll find that an overwhelming number of early pioneers who shaped its history were women. On both a technical and creative level, women have and continue to revolutionalize electronic music. As the genre developed throughout the 20th century, a hidden wave of sonic sorceresses played a pivotal role in pushing the boundaries of what was deemed possible within the realm of electronic music, experimenting with instruments and tape manipulation, influencing generations of electronic musicians. In the annals of music history, certain names and narratives have dominated the collective consciousness, while women sculpted soundscapes from the shadows. Let’s change the tune and hear from some of those unsung heroines…

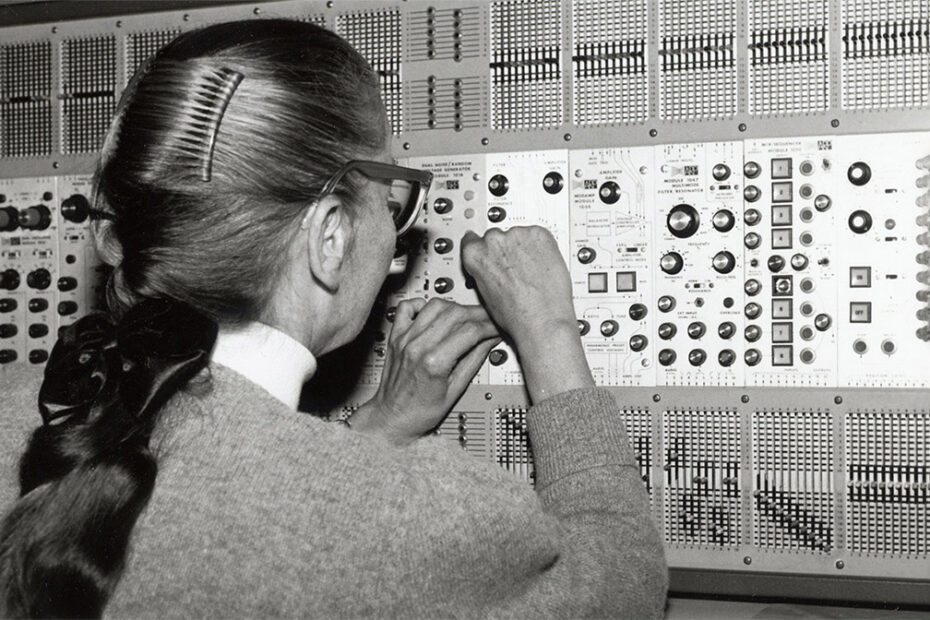

The orchestrator of a new sonic frontier, British composer Daphne Oram co-founded the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, one of the first outlets using incidental sound. She was also heavily involved in musique concrète, a genre using recorded sounds as its material, often put together as a montage. She later set up a studio to develop Oramics, a drawn sound technique in which the recording is represented in images on paper or film. Having such control over musical production was revolutionary. As Oram said, “Every nuance, every subtlety of phrasing, every tone gradation or pitch inflection must be possible just by a change in the written form.” If you want to dive in more, Oram’s 1971 book An Individual Note of Music, Sound and Electronics is a fascinating exploration of the physics and philosophy of music.

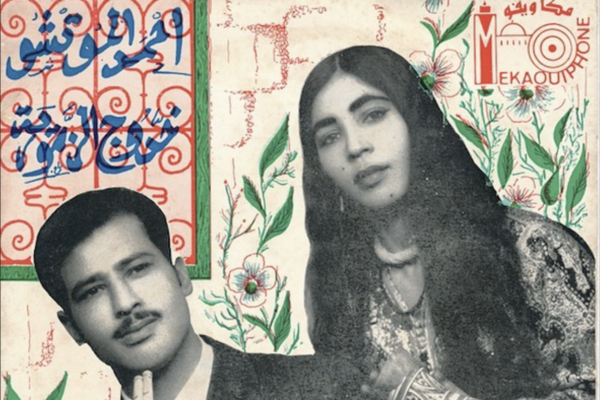

As we’ve previously reported, “Anaïs Nin is our favourite breed of artist: the kind who just can’t be bound to a single era, movement, or category. Diarist? Definitely.” But the jack of all trades also produced some pretty out-there electronic recordings. Her 1952 track “Bells of Atlantis” “gives today’s Coachella-bound DJs a run for their money.” As a young girl growing up in Paris, Nin developed an appreciation for Impressionist compositions by artists like Claude Debussy. Her electronic music work was a collaboration with two of the industry’s pioneers, the couple Bebe and Louis Barron (whose soundtrack for the 1956 movie Forbidden Planet was the first with a fully electronic score).

“Bells of Atlantis” was inspired by Nin’s 1947 prose poem “House of Incest,” which was about the narrator’s “escape from a women’s season in hell.” The resulting film also features visuals by her first husband, Hugo Guiler, and while there isn’t much of a narrative thread to follow, it provides a trippy journey into the mind of one of the 20th century’s most influential thinkers.

Child prodigy Clara Rockmore may have been a violin virtuoso, but she built her career as “the first true master of the theremin,” the world’s first mass-produced instrument. Born in Vilnius, Rockmore began studying at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory at the age of four, standing on the table for the audition because she was so little. Sadly, arthritis prevented her from continuing with violin, but she found that the theremin required the same intricacy and precision. She had been introduced to the instrument, which relies on metal antennas and the user’s hands to oscillate frequencies, by its inventor, physicist Léon Theremin. (The two had a complicated relationship: Rockmore influenced the design of the instrument to make it more sensitive while Theremin never got over his unrequited love for her.) Meanwhile, Rockmore’s perfect pitch led to her performing with orchestras around the US. While the instrument’s popularity waned, Rockmore released a successful album, The Art of the Theremin, with her sister, the pianist Nadia Reisenberg.

Else Marie Pade was not only the first Danish composer of electronic but also a member of the resistance during the Second World War (notably alluding capture after spitting on a German soldier). Bedridden as a child, Pade learned to make “aural pictures” of the sounds of the world around her. When eventually imprisoned during the war, she scratched out musical scores on the cell walls. After liberation, she heard a radio program on musique concrète and its creator Pierre Schaeffer. While Pade had started in piano, her musical path switched as she traveled to Paris to meet Schaeffer, who ended up becoming her teacher. One interesting piece was a version of the “Little Mermaid” in which above-water sounds were recorded from real life, whereas all the sounds beneath the surface were electronic. She also made musique concrète about daily life in Copenhagen (“Symphonie magnétophonique”) and a TV ballet with dancer Nini Theilade (“Grass Blade”) But one of her most powerful works is the 1970 piece “Face It,” in which “Hitler is not dead” is repeated over and over again in Danish.

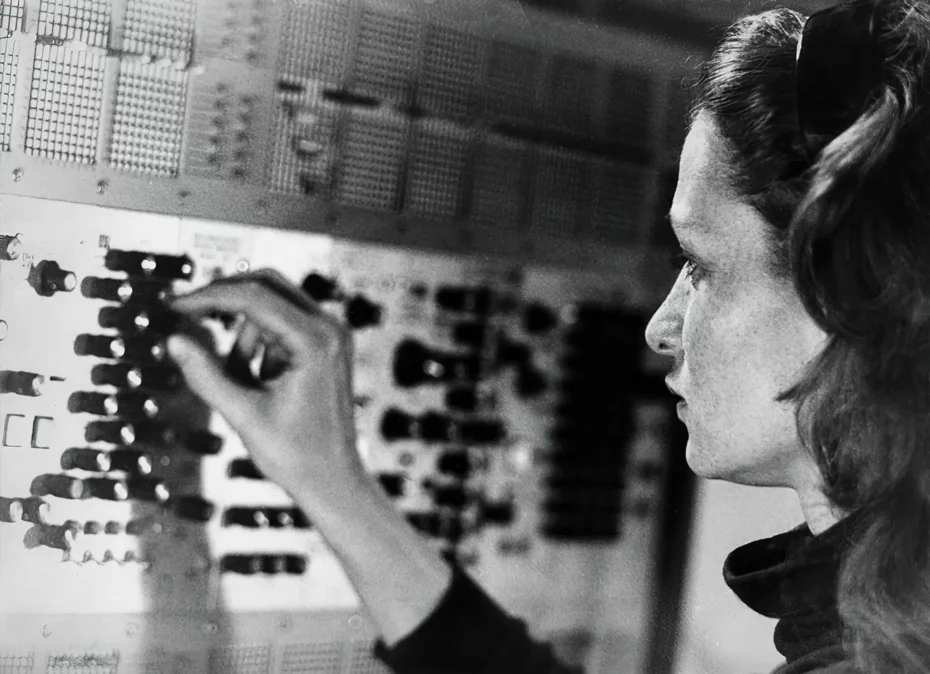

Schaeffer also influenced French musician Elaine Radigue, who developed her own unique style relying on long tape loops and microphone feedback. She was both Schaeffer’s student and involved in his Studio d’Essai, which first played a role in the French resistance during the war and later became a musical hub. Radigue married French-American painter Arman and continued to build her career recording almost solely with the ARP 2500 modular synthesizer. She was heavily influenced both spiritually and creatively by Tibetan Buddhism, making music inspired by the famed yogi Jetsun Milarepa.

Her masterpiece is Trilogie de la Mort, a three-hour piece that she worked on for years. It was inspired by the Tibetan Book of the Dead and follows the six states of consciousness. Since 2004, she has focused on acoustic music, including composing for cello, basset horn and harp.

Delia Derbyshire has been called “the unsung heroine of British electronic music,” with her work on shows like “Doctor Who” and for theatrical productions influenced later electronic acts like Aphex Twin and the Chemical Brothers. Growing up during World War II, Derbyshire said that “the radio was my education” and started her career at the BBC and its BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Under the pseudonym Li De la Russe (an anagram of Delia and a reference to her hair color), she also contributed to the Standard Music Library, which publishes sounds to be used in a range of commercial and entertainment media. Sadly, Derbyshire stopped producing music in 1975 and only picked it up again just before her death in 2001. Luckily, her archive of over 250 reel-to-reel tapes was given to composer Mark Ayres, who worked to preserve and digitize them. Some were used in the 2020 film Delia Derbyshire: The Myths And The Legendary Tapes.

When Kim Petras recently won a Grammy for her song “Unholy,” with Sam Smith, she became the first openly transgender person to be awarded this honor. But in fact, she was not the first trans person to receive this top music award: Electronic music pioneer Wendy Carlos received three Grammys back in the 1960s for Switched-On Bach, in which she reinterpreted the classic songs using a Moog synthesizer.

Carlos studied at Colombia University and assisted famed composure Leonard Bernstein in putting on a night of electronic music. Her collaboration with classical musician Rachel Elkind resulted in Switched-On Bach, featuring the German composer’s music played on a Moog modular synthesizer. It was a time-consuming and costly production, taking over 1,100 hours in the studio, given that the synth could only play one note at a time. But it ended up being a commercial and critical hit. In addition to further promoting synth music, Carlos also saw her career blossom, as she went on to compose the soundtracks for A Clockwork Orange, Tron and The Shining. Over the years, she has also produced electronic covers of songs pop songs like “Eleanor Rigby” and “What’s New Pussycat?” and ambient music with sounds recorded in nature. Outside of music, Carlos is an accomplished eclipse photographer.

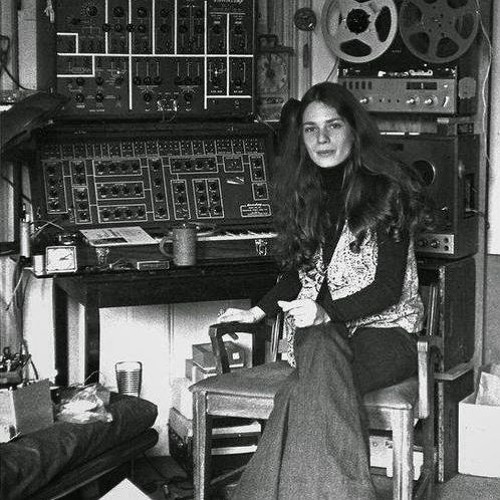

American composer Laurie Spiegel has straddled the creative and technical side of music production as a leader in New York’s new-music scene and for her algorithmic composition software, known as Music Mouse. As a child in Chicago, she learned to play banjo, guitar and mandolin by ear. She worked on many early experimental compositional and image-generation software projects, including at the famed Bell Labs and Apple. Her tech innovations have not removed the human element from her art: “I automate whatever can be automated to be freer to focus on those aspects of music that can’t be automated. The challenge is to figure out which is which,” she said in an interview for the book Women Composers and Music Technology in the United States. Some of her most notable accomplishments include her version of Johannes Kepler’s “Harmonices Mundi,” which was included on the golden record sent on board the Voyager spacecraft in 1977. Another song called “Sediment” was included in The Hunger Games film.

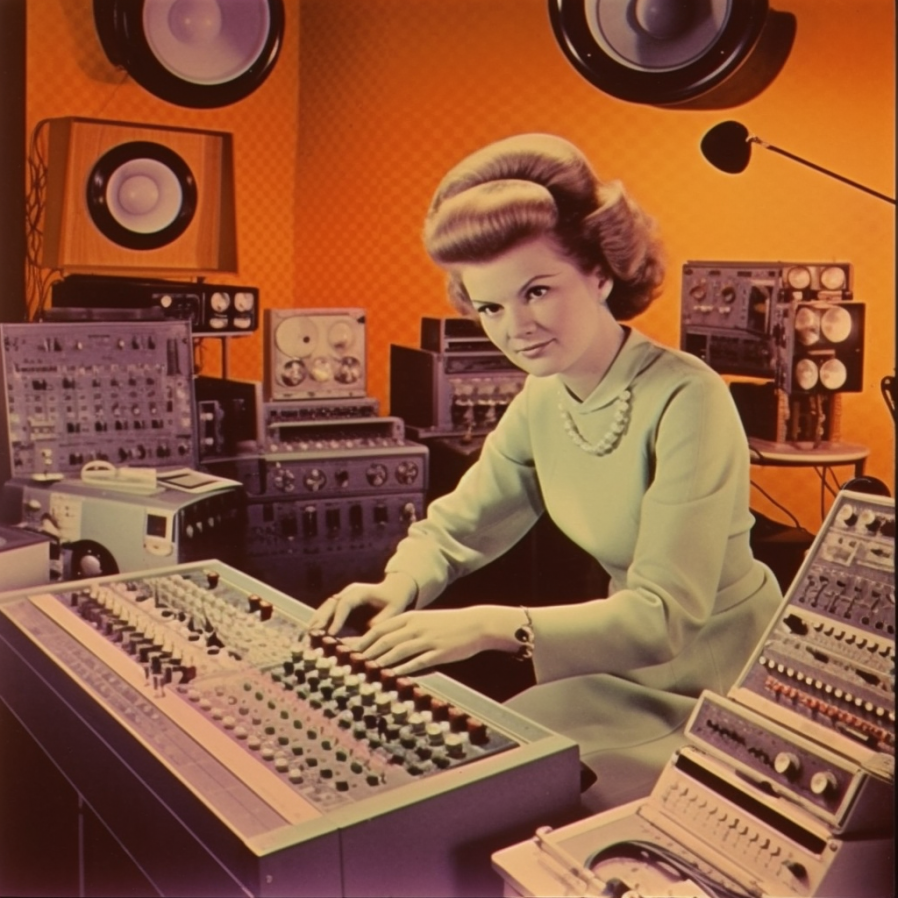

Suzanne Ciani made a name for herself in the New Age genre, as well as experiments with quadrophonic sound using four audio channels to create what we would refer to nowadays as surround sound. Ciani collaborated with artists (she contributed the “swoosh” sound to “Afternoon Delight”), worked on jingles (including the sound of a Coca-Cola bottle being opened and poured that was widely used in ads) and showed off her skills on the David Lettermen Show:

Another highlight was when she composed the soundtrack for Lily Tomlin’s movie The Incredible Shrinking Woman, making her the first solo female composer of a Hollywood film. On her beloved Buchla synthesizer, she followed her “destiny” to release her own albums and to date, has released 15 studio albums, most known for the song “The Velocity of Love.”

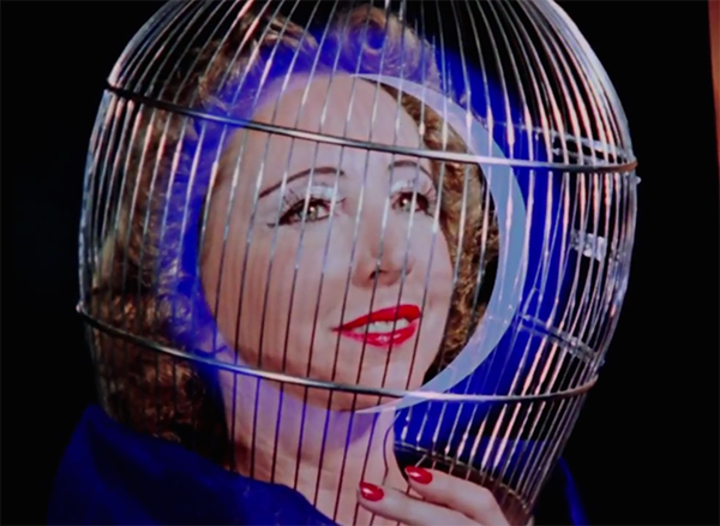

Finally, let’s meet American electronic musician Susan Dietrich Schneider, who has built a career as “The Space Lady,” The daughter of classical musicians, Dietrich Schneider began as a street musician in Boston and San Francisco, playing accordion covers of rock standards (like the appropriate “Starman” and “Across the Universe”) wearing a signature silver helmet with rings and a flashing light: It’s no surprise that she was dubbed “The Space Lady.” She switched to the Casiotone MT-40 keyboard, on which she played the song “Synthesize Me,” written by her ex-husband. Despite developing a small following as a true outsider artist, she retired from music to care for her parents and become a nurse in the 2000s. Although her marriage to fellow musician Eric Schneider led her to return to music, landing a record deal and touring the world. She even made The Guardian’s list of “The 101 Strangest Records on Spotify.”

We hope you enjoyed our playlist of electronic instrument and tape manipulation legends. And if you want to explore more, check out the 2020 documentary Sisters With Transistors.