It’s as American as Apple Pie in all its neon-lit glory, evoking our collective cultural memory of 1950s road-tripping, film noir fugitive hideouts and the golden age of kitsch. The motel is as much a part of the American open road as the gas station and the roadside diner, an indispensable amenity to the roving motorist; the comfort of a flickering sign in the black of night promising “vacancy”. But what’s the story behind the omni-present American motel? Today, we’re hopping in our digital Cadillac for a little drive down memory lane– first stop? Our planet’s first ever motel in sunny, central California, to learn the essentials– like, why call it a motel in the first place?

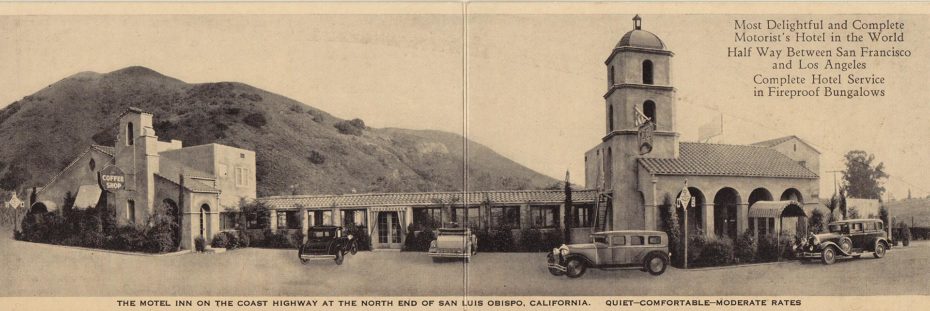

In December of 1925, the Spanish-revival doors of the Milestone Mo-Tel Inn swung open to motorists mid-way between Los Angeles and San Francisco, offering a luxurious overnight stay by any standards. In conceiving a name for his first hotel, untrained architect Arthur Heineman of Chicago, abbreviated “motor hotel” to “mo-tel” after realising he couldn’t fit all 19 letters of “Milestone Motor Hotel” on his rooftop sign.

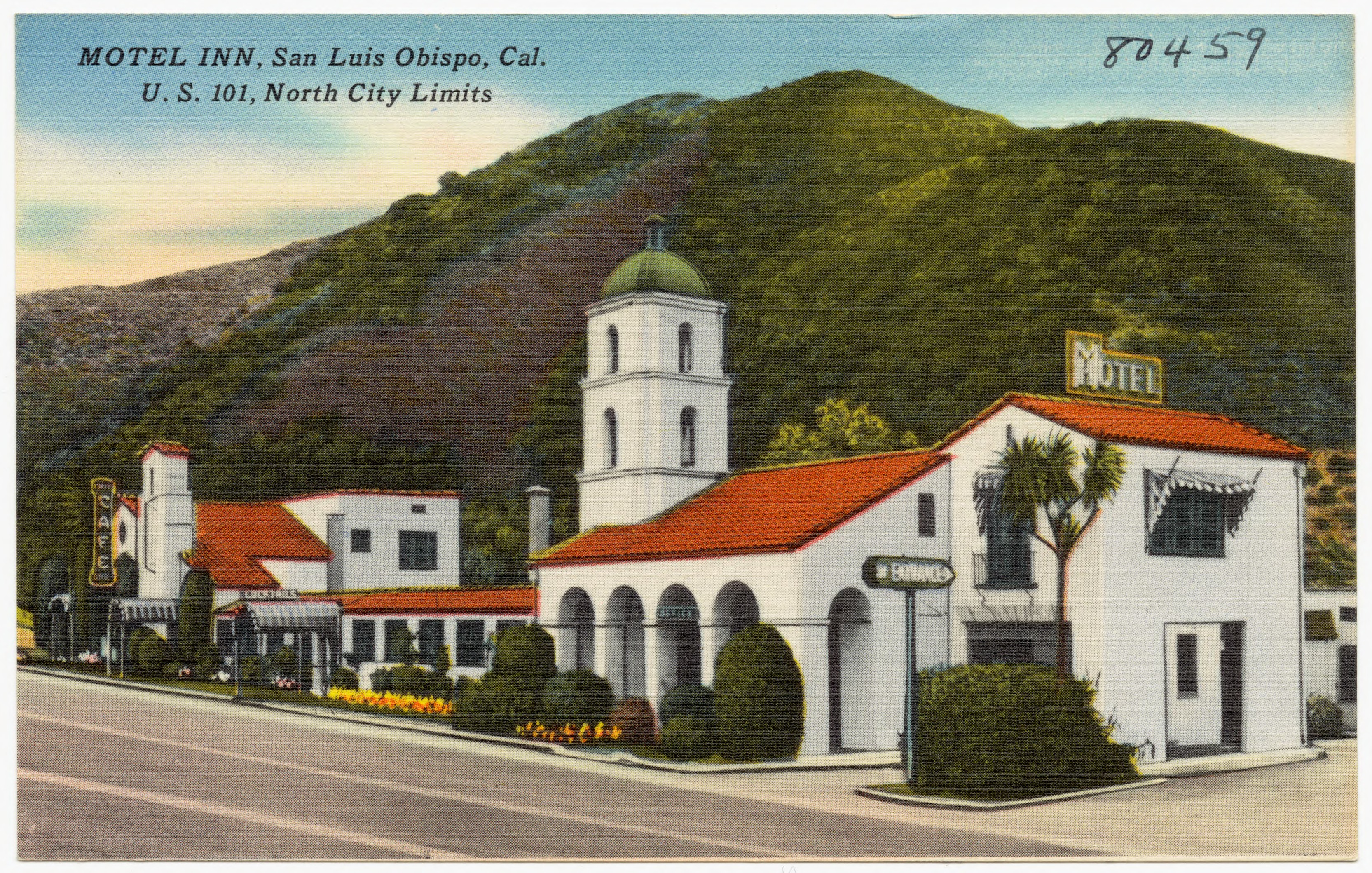

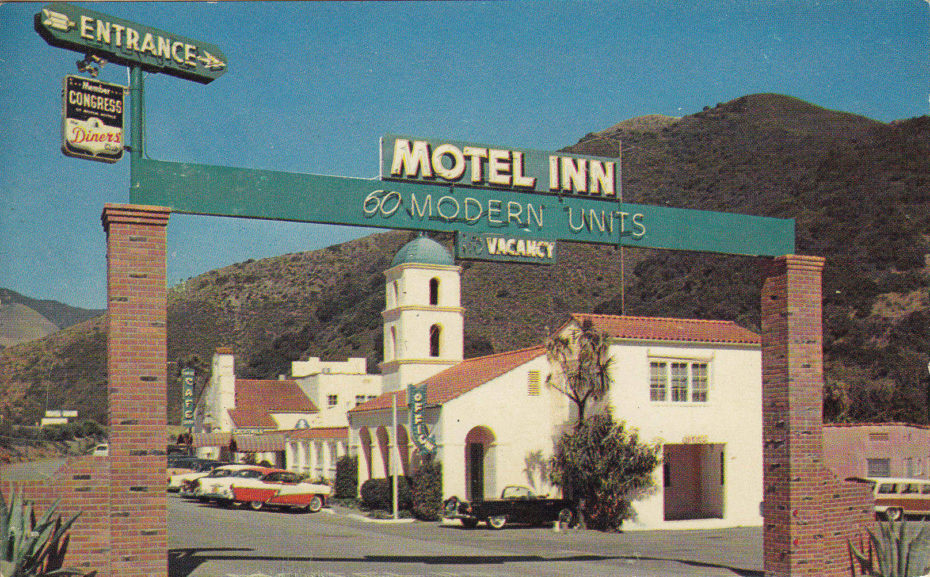

A postcard from the 1940s. He should have trademarked the word right then and there, yet for reasons unknown, he was unable to. The plan was to open a chain of motor inns around the country under the novel “motel” concept, but without that all-important trademark, his competitors quickly hijacked the idea. With bigger, brighter and cheaper copycat “motels” popping up nearby on Route 66, and the looming financial challenges of the Great Depression, Heineman’s legacy was doomed to become a mere footnote in history. Despite being the inventor and primary architect of the an American icon, Milestone Mo-Tel Inn would be the first and last motel Arthur Heineman would ever open.

A postcard from the 1940s. He should have trademarked the word right then and there, yet for reasons unknown, he was unable to. The plan was to open a chain of motor inns around the country under the novel “motel” concept, but without that all-important trademark, his competitors quickly hijacked the idea. With bigger, brighter and cheaper copycat “motels” popping up nearby on Route 66, and the looming financial challenges of the Great Depression, Heineman’s legacy was doomed to become a mere footnote in history. Despite being the inventor and primary architect of the an American icon, Milestone Mo-Tel Inn would be the first and last motel Arthur Heineman would ever open.

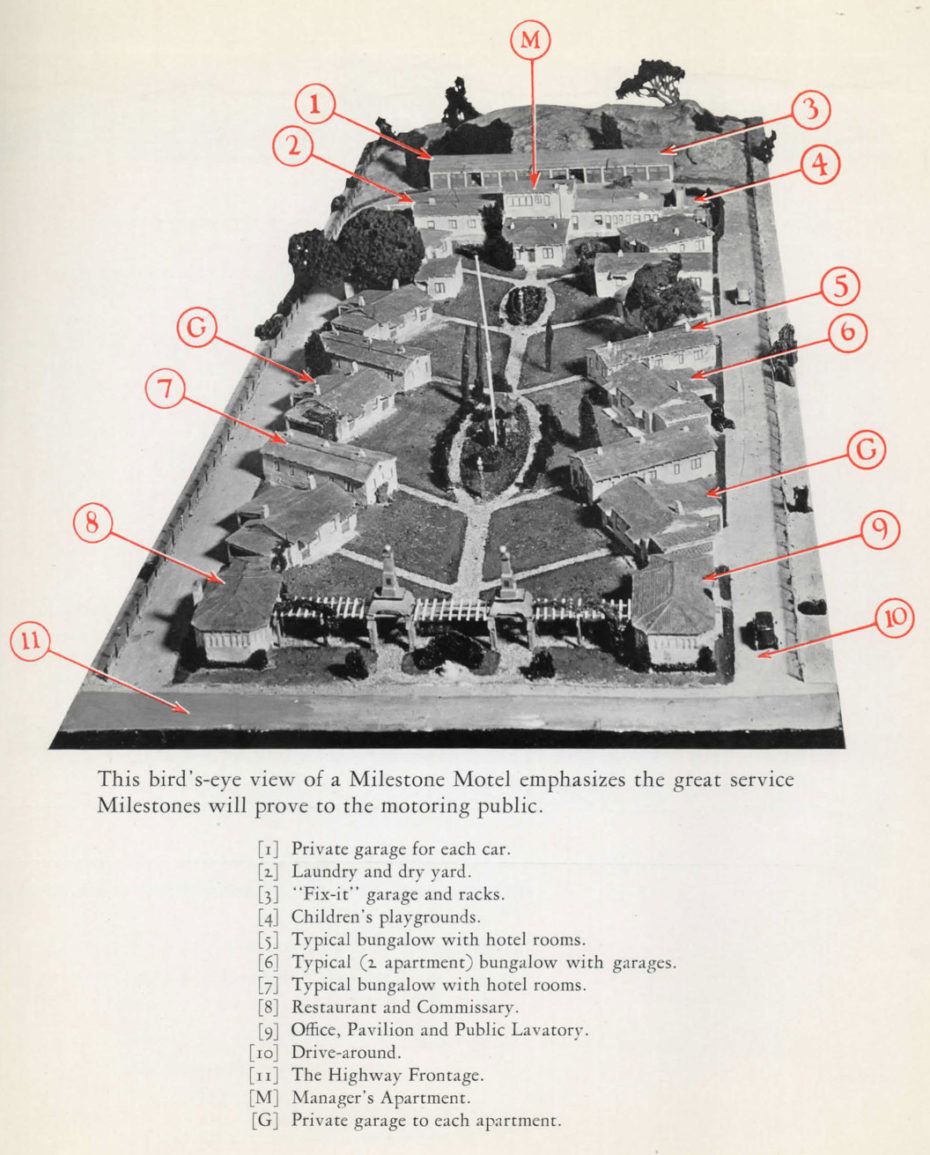

For $1.25 a night (around $17 today), motorists had access to cutting-edge conveniences. The anatomy of the motel was simple: cater to drivers and their cars by providing each customer with a garage space, laundry and shower facilities, and even a little grocery store– and above all, make it pretty. The bell tower was modelled after the Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, handsome columns lined the halls, and, according to a 2014 article in The Tribune, Joe DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe even stopped there during their honeymoon.

The Milestone was a real testament to its name, offering a new breed of accessible luxury to the travelling Average Joe (and movie stars alike). But to really understand why it was such a novel concept, we need to look at what was available to road travellers before the motel came along…

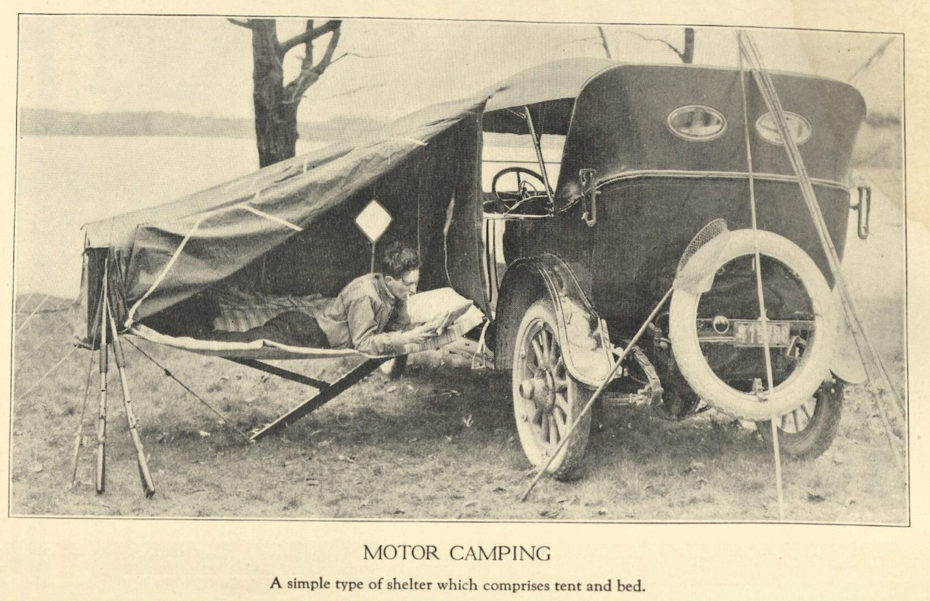

It wasn’t until the 1930s that the first travel trailers appeared on the market, and prior to that, the choice for long-distance motorists was to either pitch a tent by the side of the road or adapt their cars with bedding or even makeshift kitchens.

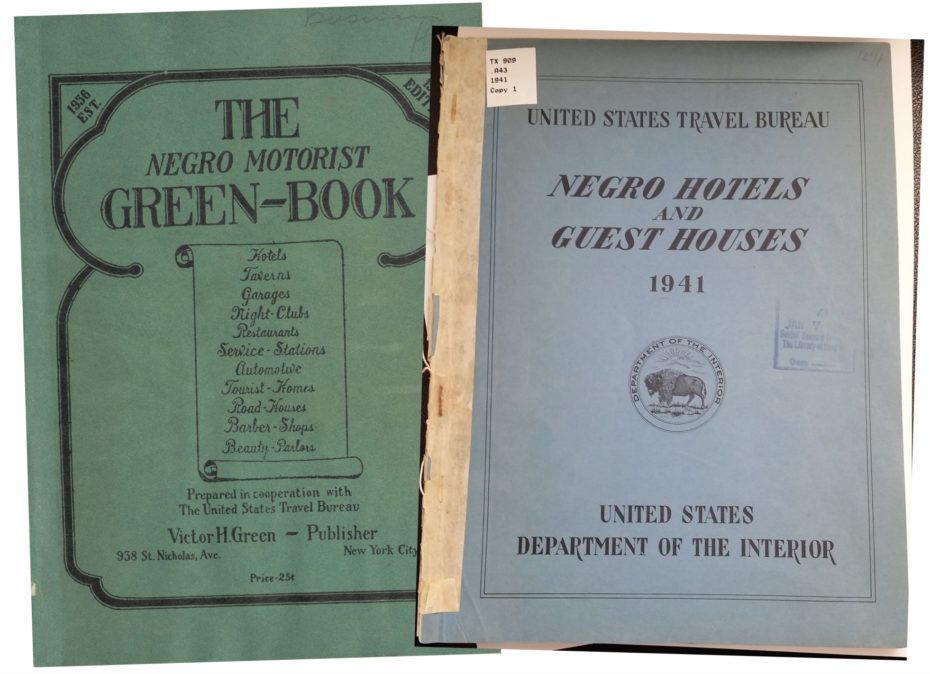

During the Great Depression, enterprising folks who owned land along the American highways began building cabin camps; primitive cost-effective structures offering basic shelter, which came to be known as “tourist homes”. At the lowest end of the burgeoning industry were the tourist homes scattered around Jim Crow’s Deep South, opened by African-Americans to answer to gaping hole of lodging offered to travellers of colour:

There were things money couldn’t buy on Route 66. Between Chicago and Los Angeles you couldn’t rent a room if you were tired after a long drive. You couldn’t sit down in a restaurant or diner or buy a meal no matter how much money you had. You couldn’t find a place to answer the call of nature even with a pocketful of money…if you were a person of color traveling on Route 66 in the 1940s and ’50s.

–Irv Logan, Jr.

Guides such as The Negro Motorist Green Book (1936–64) and the Directory of Negro Hotels and Guest Houses in the United States listed accommodations, restaurants, gas stations and other friendly (or just tolerant) travel stops for the African-American motorist.

For the (white) American traveller in search of more modern amenities, the next step up from travel trailers and tourist homes would soon arrive in the form of “cottage courts” and “tourist courts”, the motel’s most immediate predecessor. At a higher price than the tourist home, motor courts had electricity, indoor private bathrooms, convenience stores, gas stations– and the all-important assigned parking space.

They aspired to create a home-away-from-home persona, like the “3-V Tourist Courts” (pictured above). Built in Louisiana in 1938 as one of the first “motor courts” in the country, it’s still in operation today.

The single story buildings were quick & easy to construct and the motor court became popular Mom-and-Pop businesses, often as quirky as their owners who lived on the fringes of society.

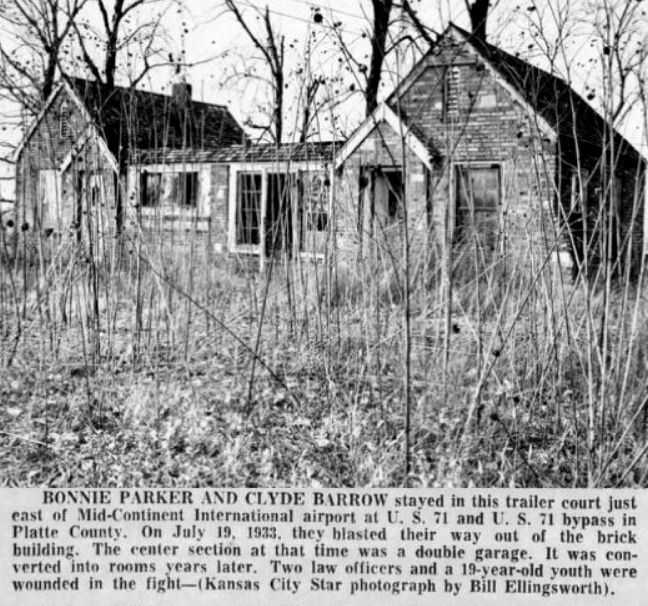

It’s precisely the kind of clapboard cottages where Bonnie and Clyde would hide out, and certainly strikes a resemblance to Missouri’s “Red Crown Tourist Court” motel, where the couple had a shoot-out with police in the summer of 1933.

The Red Crown Tourist Court no longer exists, but you can stay in room #207 of Texas’ Alcalde Motel, where the two jumped out of a second story window to escape law enforcement. Aside from providing refuge to Bonnie & Clyde, who came to embody the rogue romanticism (and terror) of the open road and mounting crime in the US, motor-friendly accommodation provided convenience above all, as America cemented its love affair with the automobile.

And it was Arthur Heineman‘s idea to combine the individual cabins of the cottage courts under a single roof that truly gave birth to the motel as we know it today.

“A traveler arriving at night, or at any other time, need not climb out of his car and go into the office to register. Instead, the man in charge comes out to the car and one may register without leaving the car at all. That done, an escort is sent with the traveler to show him his rooms, his apartment or whatever kind of combination in rooms he wants.” – San Louis Obispo Telegram, 1925

Twenty-five years after the conception of the first motel, the post-war economic expansion saw to it that by 1950, there were over 50,000 motels catering to millions of Americans during the golden age of travel. But things came to a halt with the Great Depression– which isn’t to say motor hotels went out of fashion– they just became less fancy. Arthur Heineman ultimately lost his motel, the world’s first, to foreclosure.

The business remained running under different ownership until the 1990s, by which time the original Mo-Tel Inn had fallen into serious disrepair before finally closing its doors for good. As for the faux-pueblo property? In an odd twist of fate– it’s still there.

Sadly it’s no longer a motel, but a rather sorry-looking administrative building for the neighbouring “Apple Farm Inn”. While Heineman’s 1920s design has lost most of its original infrastructure, except for a few walls around the old bell tower (the motel office), that the world’s first motel is still standing is still pretty amazing. You can even find the seventies-era sign still standing and a plaque, commemorating the motel’s claim to fame.

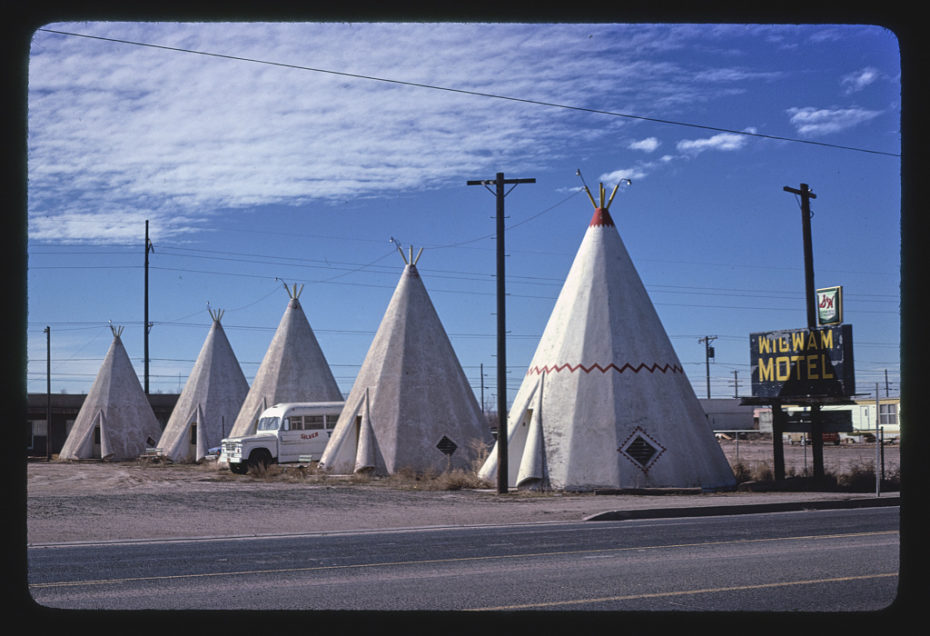

The motel industry reached its peak in the 1960s, when “Googie” architecture was taking over the American roadside. Air conditioning and colour TV was proudly indicated on the extravagant midcentury signage and the American vacationer started to get used to gimmicks like “Magic Fingers” vibrating beds (invented by John Houghtaling in 1958) and more imaginative concepts. From overnight experiences aboard retired train carriages to those questionable tipis (incorrectly dubbed, “wigwams”), motel marketing became an aggressive sport.

Known as the “Wigwam Villages”, this chain became perhaps the most iconic of American motel industry, popping up across the West and even in the South. Only a few remain today, but folks can still pull up with their stationwagon and sleep in a concrete tipi should they please (visit their site here).

Fun fact: remember those classic, diamond-shaped key fobs we associate with old motels? They doubled as postage-paid “stamps” for motel customers who forgot to return room keys. Guest could simply send them back to the motel by plopping them in a mailbox wherever they should be in the world. The original tags with examples of postal fees are tougher to find these days, so hold on to it if you should find one.

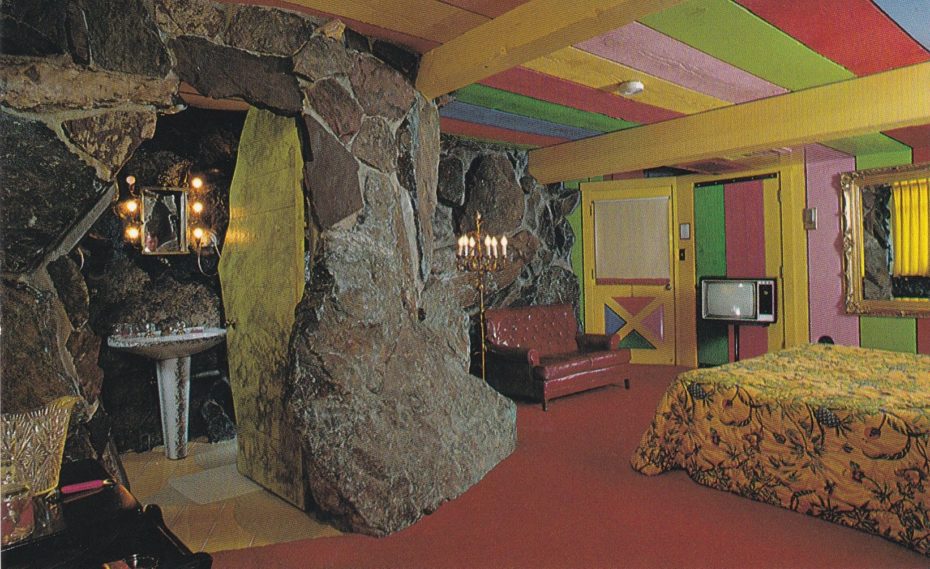

We’d also be amiss if we didn’t mention the Mo-Tel Inn’s now-iconic neighbour, the Madonna Inn. Founded in 1958, it’s a veritable palace of kitsch with rooms that deserve their own article, and a colour palette pulled straight from Barbie’s brain. It’s also a lesson in the staying power of “more is more” in the motel industry…

The above mentioned motels are the original hold-outs of one of the most iconic eras of American history– and with the influx of new freeways, it’s a miracle so many of them survived. At its peak in the 1960s, the motel industry boasted 61,000 properties. In the past decade, the number of registered motels has fallen to as low as 16,000.

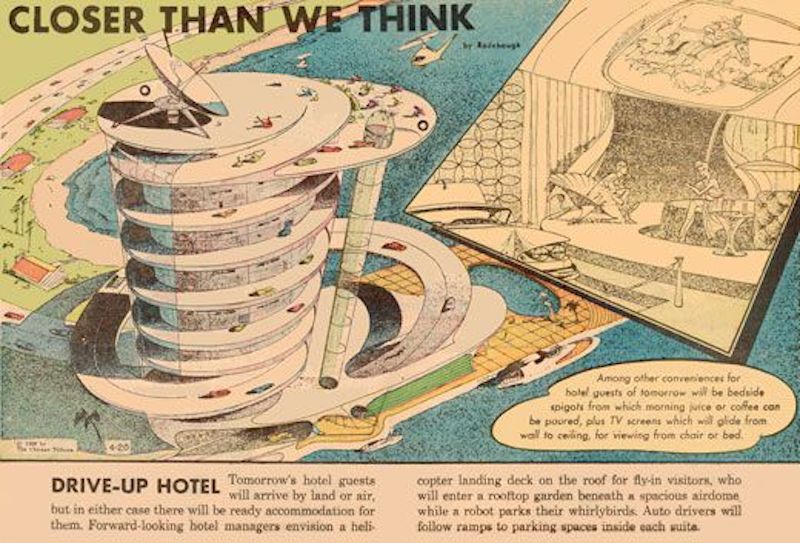

The dinosaurs of the industry; older, less tech-friendly motels that catered to history’s Bonnie & Clyde’s, are almost an endangered species. And while we’ll continue to seek out the admirable efforts of those trying to preserve the beloved “Mom & Pop” motor hotels of yesteryear, we can’t help but wonder– what’s next for the accommodation industry?

What will the 22nd century “motel” even look like? If the Jetsons are anything to go by, we should be floating into the roadside lodgings of the future by way of flying car. Flotel? Flytel? It doesn’t quite have the same ring as “motel”, but we’ll keep brainstorming. Race you to the trademark office.