You shall go to the Ball! The Belle Époque was that party at the end of the 19th century when European influence, wealth, culture and glamour reigned supreme. All wanted to join the party, and Detroit, that French Trading post on the North American lakes, was up for it. Prosperous and progressive from its new world trading position, Detroit with its French roots was known in the late 19th century as The Little Paris of the Midwest. The city was a flashy debutante – bold and brash, but unfortunately, the party wouldn’t last long. Looming World War I would put out the party lights of the Belle Epoque and Detroit’s French fancy would soon be left in the dark.

The city of Detroit’s name is derived from le détroit du Lac Érie, referring to the narrow linking waterway connecting the two great North American lakes, Huron and Erie. Detroit was settled and expanded to exploit a strategic geographical position as an easy landing and ferry point for goods and trade across the great lakes, but also as gateway to the American heartlands from Quebec. The French founded Detroit and protected her with the star-shaped Fort Lernoult, positioned inland and west of the settlement. During the 18th century, when the Seven-Years War raged between Britain and France for control of the North American continent, the fort fell to the British in 1760, who then administered it the young town from Quebec. In turn, the British lost Detroit during the American Wars of Independence and from 1776, Detroit became part of the new United States of America.

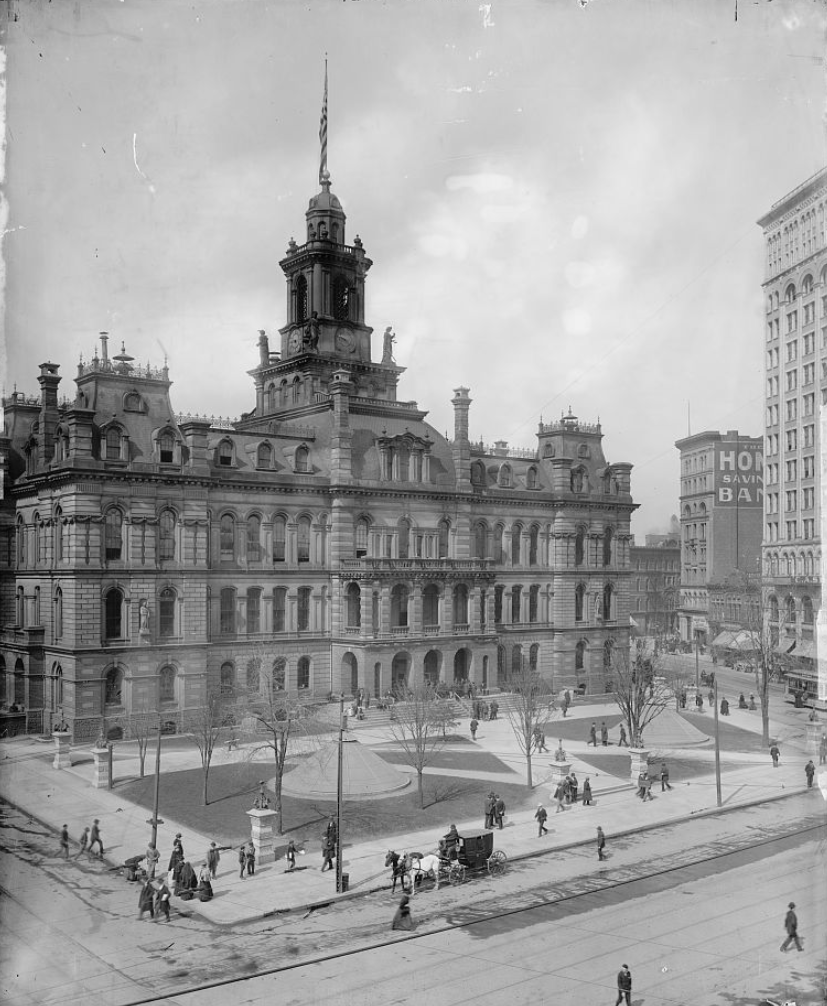

Despite being almost entirely destroyed by fire in 1805, the City of Detroit continued to prosper, fuelled by ever-expanding trading and manufacturing enterprises that exploited the waterways across the lakes together with the new national railroad network. Following the fire, the city was re-planned with grand avenues radiating from the Campus Martius Park, the site of the old French fort. These avenues and boulevards were lined with trees and public parks, all very reminiscent of George-Eugène Hausmann’s mid 19th century redressing of Paris with its arrays of grand boulevards and monuments.

Back in Detroit, the then new Campus Martius Park circus centrepiece sent its new streets radiating in all directions, perhaps the most notable being Woodward Avenue driven North West, directly away from the river and the old city to Brush Farm. Detroit was a blossoming city in the mid 19th century.

The 1850’s saw the redevelopment of what was previously French-owned farmland, which now bordered the new Woodward Avenue. As the city rolled inland, the demand for more and better residential space followed. Brush Park, accessible, yet sufficiently removed from the unhealthy grime, became the high society ‘must have’ residential spot for Detroit. The new suburb was laid out in a simple and efficient grid of streets and rectangular plots.

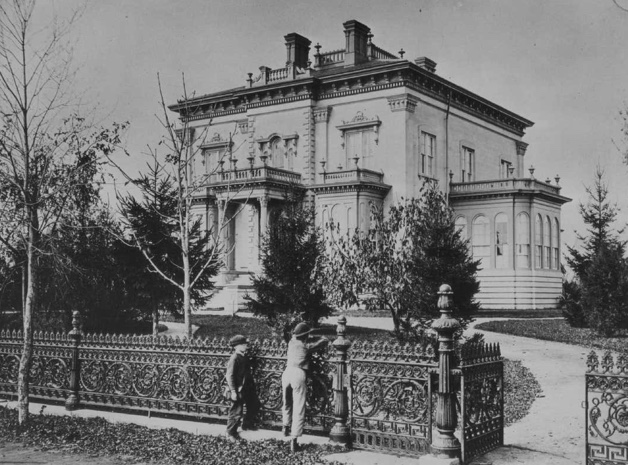

These blocks, which were quickly taken and filled with the grandest and most exuberant mansions, were all built in the most flamboyant of French styles. Indeed, so ‘French’ was this debutant suburb, Detroit was deemed The Paris of the West.

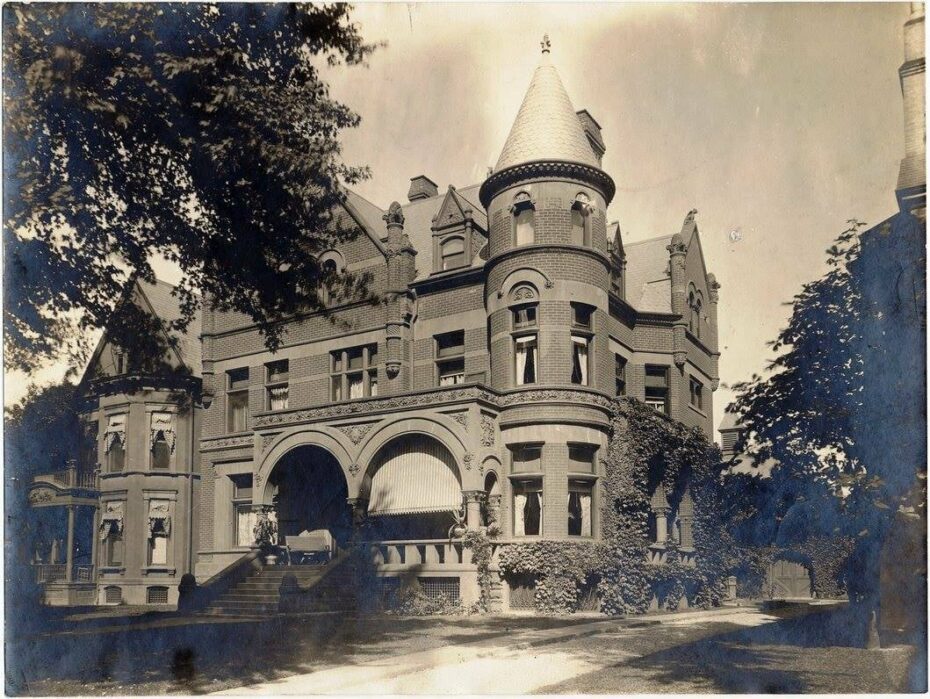

Truly a nouveau riche affair, Brush Park was an exuberant, eccentric and eclectic mix of all French periods and styles in architecture. Still within a carriage-ride distance of the city centre, these restless undulating towered piles sat shoulder to shoulder along the new grand streets, competing and screaming for attention. Riots of turrets, skyline towers, bulging domes, spiky dormers, French mansard roofs, verandas, balconies, bays and multi-columned porches – this was the Belle Époque on steroids, an outrageously confident show of symbols of commercial success.

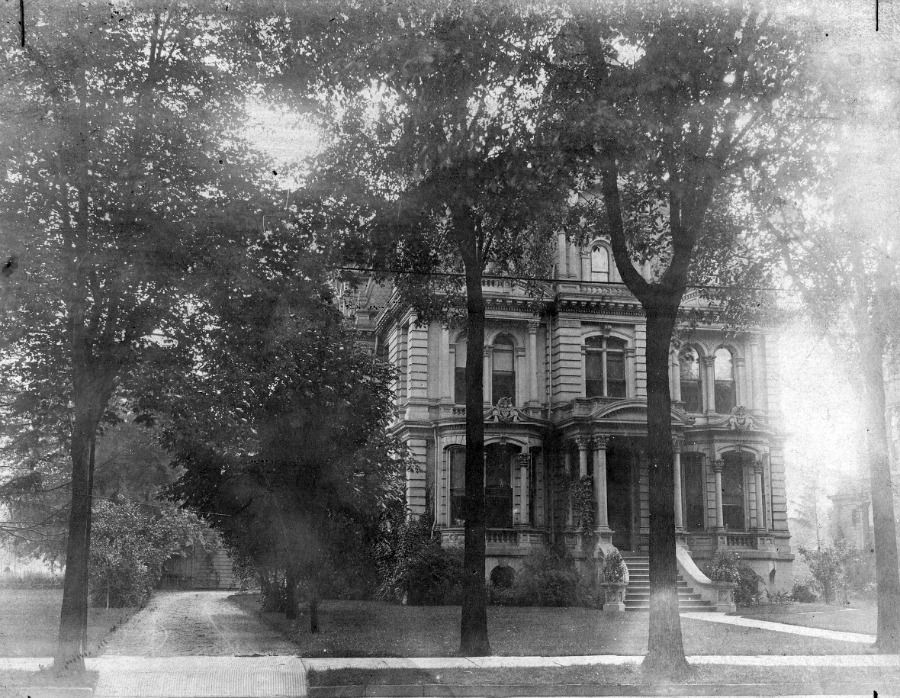

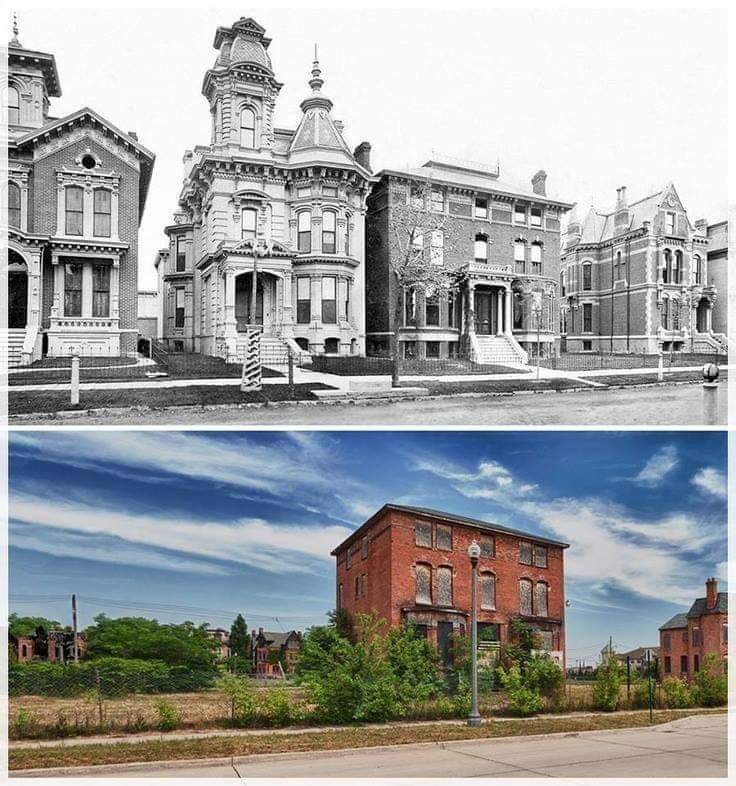

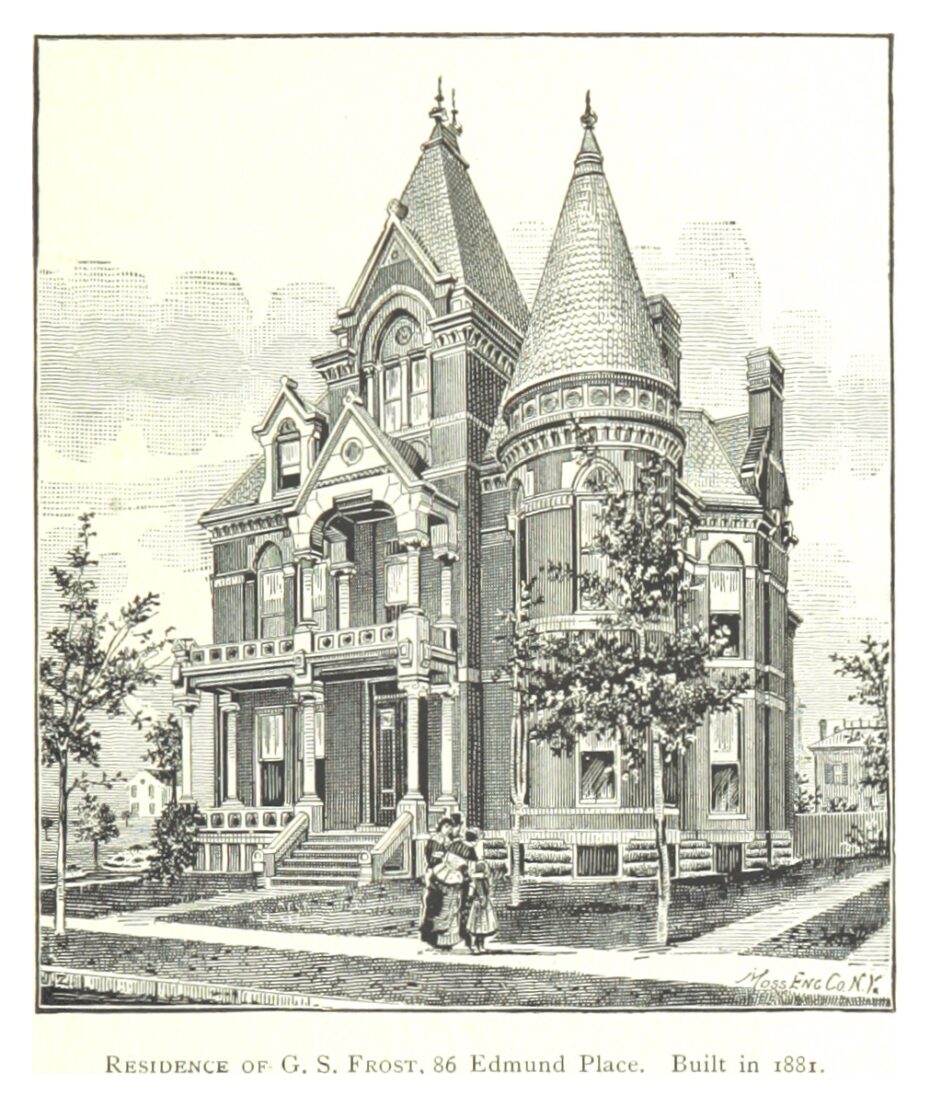

These petites châteaux were the eye candy of the boulevards. The Philo Parsons residence, the George Frost House and the Charles Noble House were supreme examples, but perhaps the most striking of these gorgeous dames was the voluptuous and curvaceous George Jerome House in 251 Alfred Street. This lady was a true baroque goddess, an undulating figure, all bulging curves, no surface left unadorned, towered, domed, mansarded, bayed, columned, rusticated, dormered, chimneyed, a lost pavilion of the Louvre corseted into a suburban street.

The most maturely designed residence, a little more grown-up, was the mansion of William Livingstone at 76 Eliot. Solid and robust with a single charming lower tower and avoiding the decorative jewellery, this is a très petit Château de Chambord à la François 1. These Duchesses of architecture stood shoulder to shoulder along the boulevards and avenues, protected on the street corners by the jagged spires and sharp pointed gables of the new Gothic Revival churches. Brush Park was most certainly a luxurious, safe and healthy enclave for those of means.

But as quickly as the flower of youth blooms, so age takes the beauty. The belles of Woodward Avenue would wither and wrinkle long before the trees in their gardens would grow to maturity. Detroit’s expansion was so dynamic and explosive that by 1880, Brush Park was now effectively ‘downtown’. The grimy city had not only caught up in less than 50 years, but surrounded it. Brush Park was now unfashionably and unacceptably close to a grubby industrial city for the healthy and wealthy. The new railways and soon to follow, automobiles, would make more and more private land accessible further afield, well away from the smoke and squalor. No sooner had the grand dames of Woodward Avenue finished dressing, the ball was cancelled! Those gilded and opulent French-inspired salons et chambres with their silk curtains and woven rugs were hurriedly stripped, packed away and vacated.

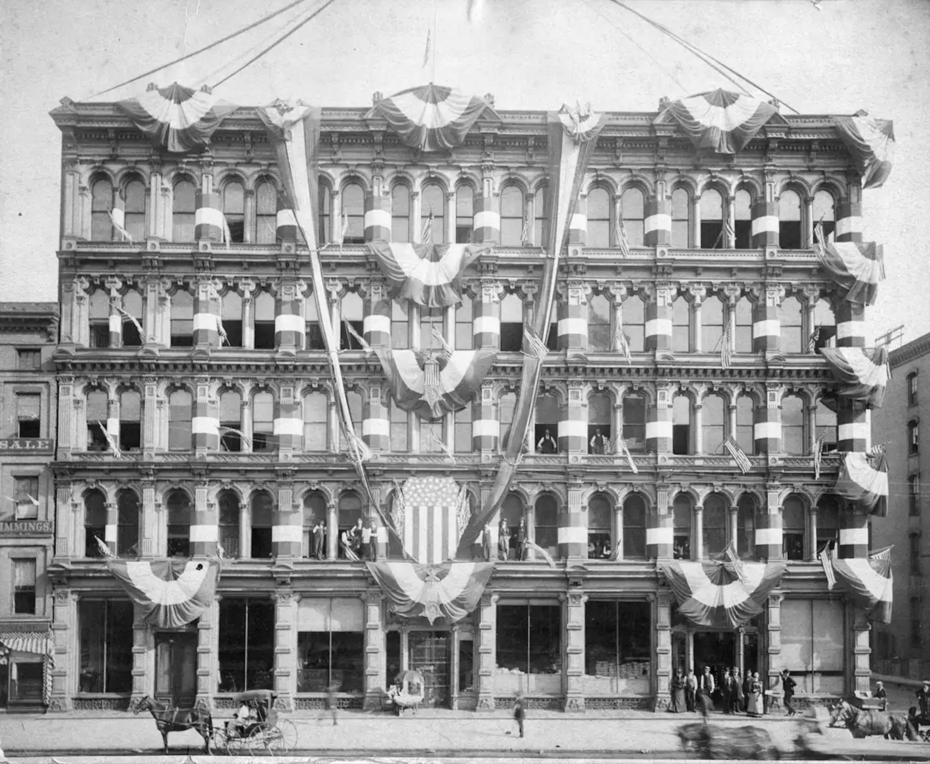

One Ransom Gillis would be hoist by his own petard and become victim of his own greed: he had built a five floor dry goods wholesale shop at 236 Woodward Avenue; he had also built his own house nearby at 205 Alfred Street.

Despite Detroit’s post World War II Motor City industrial and Motown musical success, creeping commercialism undermined the sanctity and serenity of the residential suburb. The crafted castles were left to crumble or removed in favour of the new guests. Those houses that were not torn down for retail or office replacements were left to suffer the ignominy of social decline, subdivision, a multitude of shared uses, abandonment and ruin. The party was over.

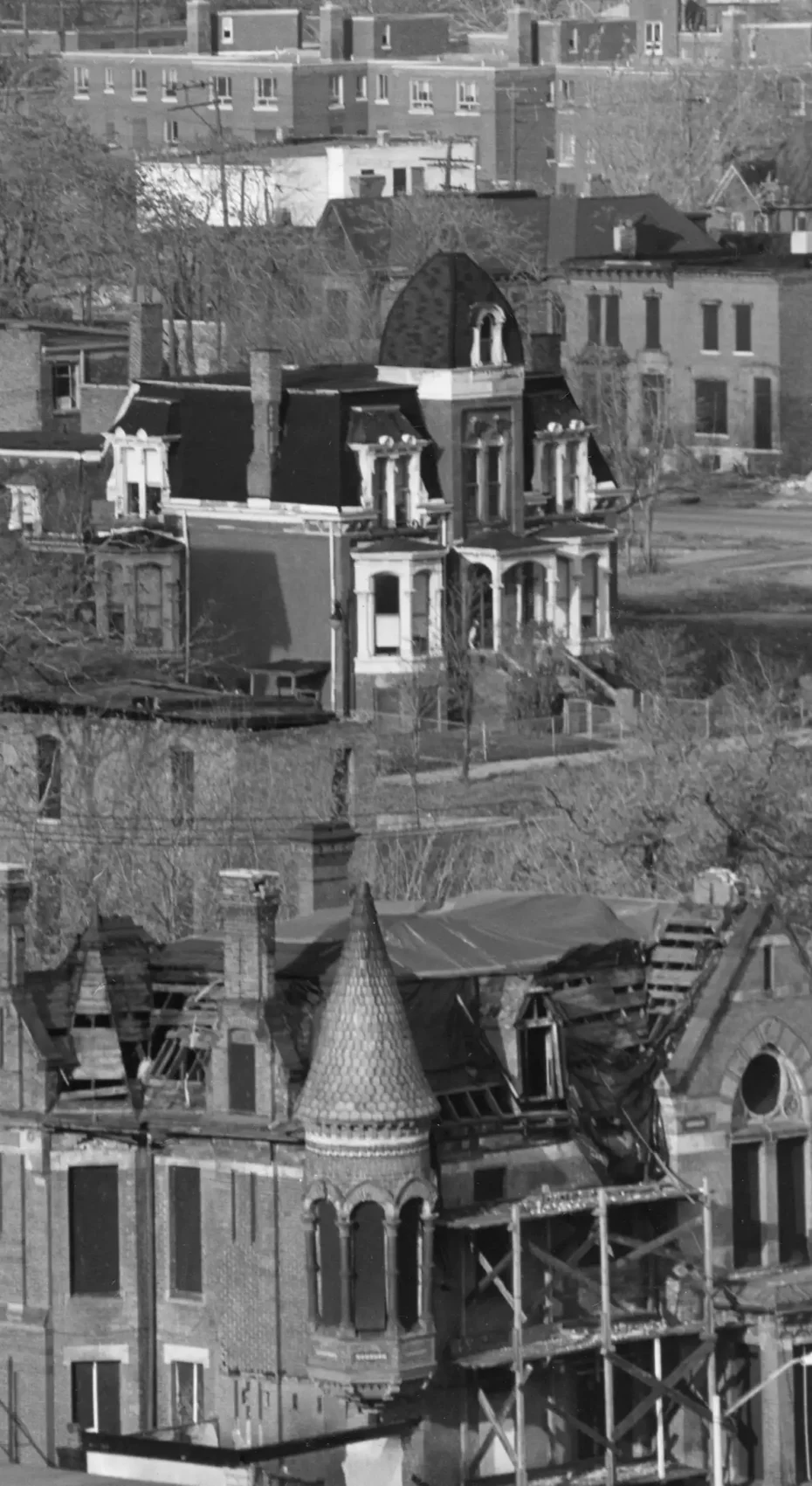

The 1960s finally saw not just the grand old mansions’ final decay but all the remaining and replacement buildings’ descent into slums and ruin. Finally in 1975, the architectural legacy was officially recognised when the area was designated a Michigan State Historical Site. But little improvement followed and by 1980, it was described as “nearly total abandonment and disintegration”. The torn building fabric became the fuel for vandals and arsonists. In order to ensure public safety, the city started a demolition programme of the ruins, removing over 70 of the shattered mansions’ remains while three of the churches were later lost in fires.

Today, Brush Park is predominantly vacant land, the remaining buildings stripped of all their architectural dress, even the gate-crashing commercial buildings have gone. Only a handful of the original Brush Park Mansions now remain, many still crumbling and standing like forgotten tombstones in a desolate graveyard.

The Alfred Street ladies are all gone, excepting one simple block, now stripped of all ornament. The turreted George S Frost house was lost in 1998, G M Traver’s house demolished in 1920 and the voluptuous George Jerome house removed in 1935. The Charles W Noble towered and mansarded pile was demolished in 1968.

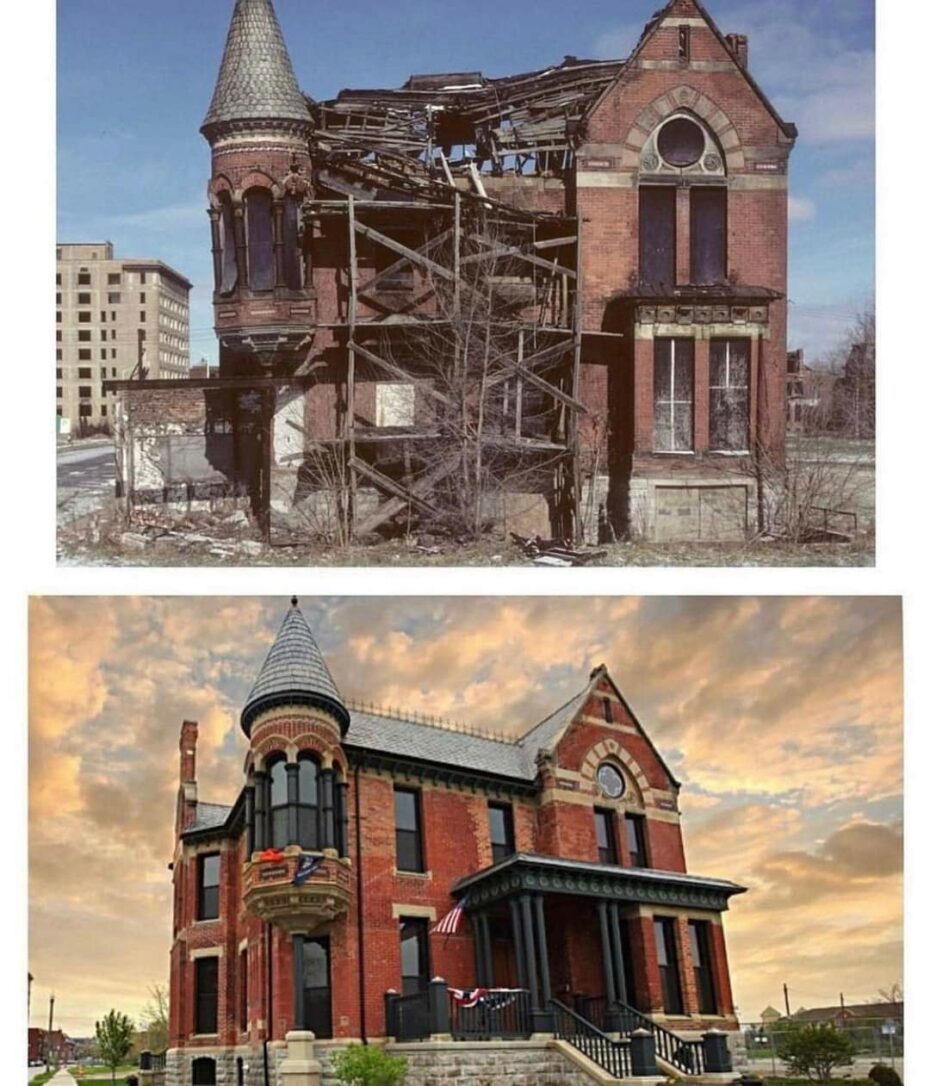

Perhaps the saddest loss is the William Livingstone house. Such a solid and sensible old girl, but she would have a dreadful end. Abandoned and left to collapse, the crisp crafted stonework and simple slate roofs had slipped, torn and wracked into a twisted mess.

But all has not been lost. Three mansions in Edmund Place have been saved and restored, while Ransom Gillis House survived and is restored as a commercial hub to serve as the HQ for the Brush Park Rehabilitation Project. Being an inner city area now, plans are afoot to seize the opportunity to revive the area as a high-density residential neighbourhood, using what remains of the old mansions to highlight and add character to the new urban blocks.

The Gilded Age was a great party, a blaze of confidence, wealth and optimism. The new century ushered in radical industrial and social change, but Brush Park was not invited to this ball. Perhaps it’s best to remember Brush Park as a joyful soirée, a fantastic fleeting moment in high society, those few years when opulence let a few play in a Gilded Age at Little Paris in the West during the Belle Époque.