When Willem Arondeus said, “Let it be known, homosexuals aren’t cowards’’, on the eve of his execution in 1943, he was speaking for himself and countless others who gave and risked their lives to end the tyranny and oppression that the LGBTQ community faced under Nazi rule. It is only in recent years that their story is slowly coming to light and we can begin to understand and acknowledge the sacrifice that was made. There is still much work to be done to uncover queer narratives from WWII’s shadows and to add them into our history books. Let’s start by meeting a few of these rainbow crusaders…

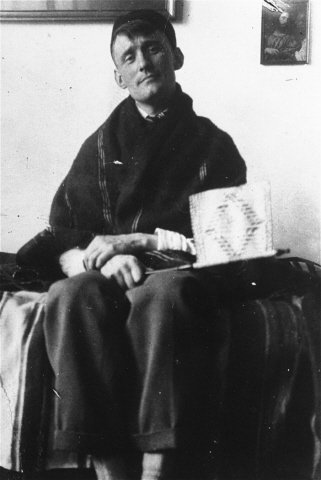

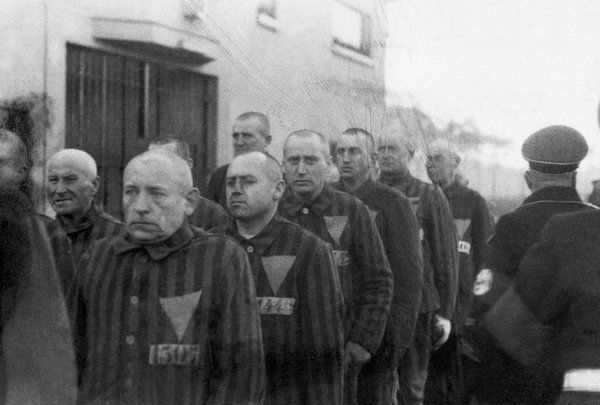

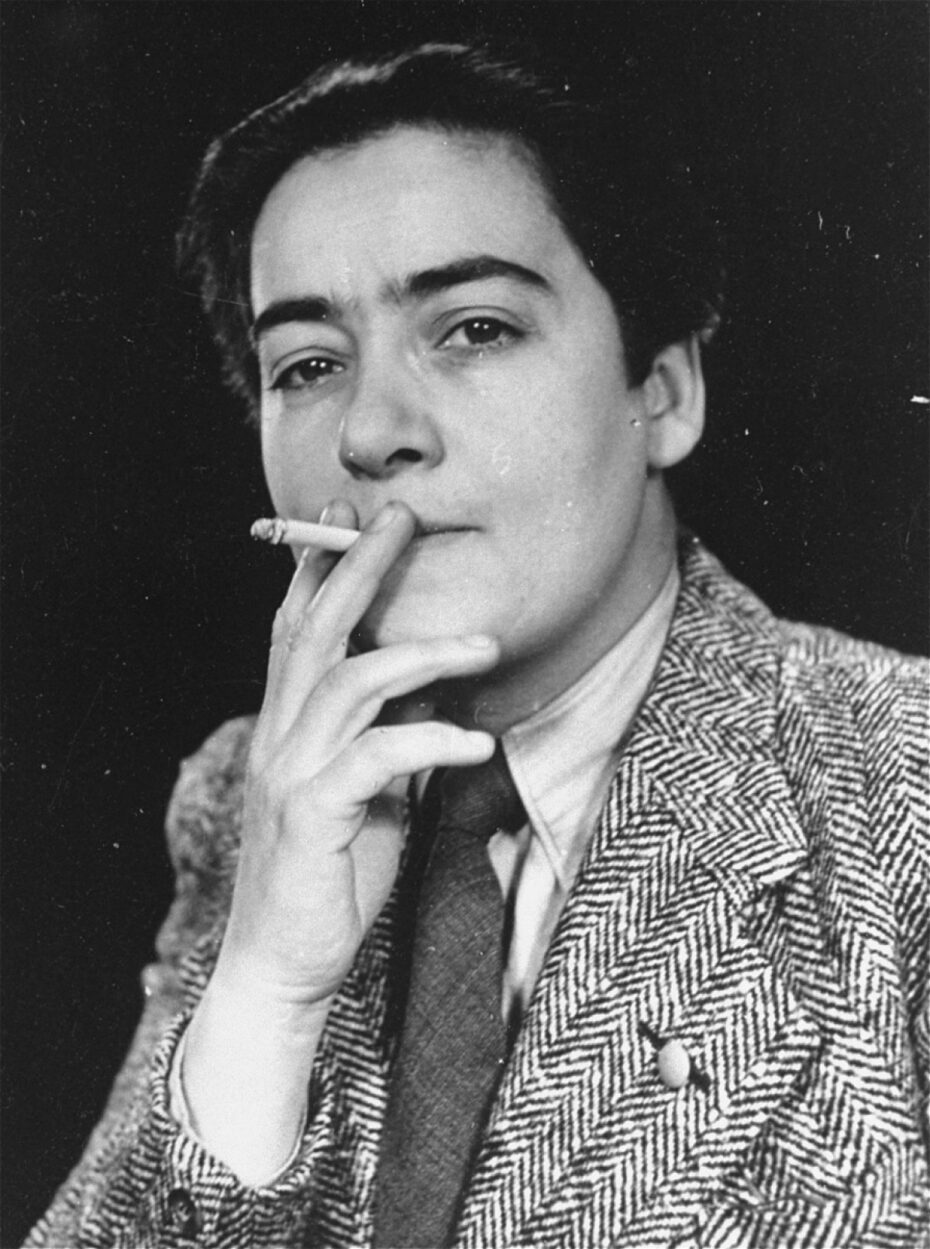

Willem Arondeus was an artist and writer; born in the Netherlands in 1894, and had been living as an openly gay man since coming out to his parents at the age 17. His father, having received this news, disowned him and so Arondeus set out on his own path in the world. Even though the Netherlands had legalised same-sex relationships since 1811, there was still a culture of discrimination against the outwardly gay. Arondeus struggled to find work and accommodation and lived a life of an impoverished artist. Although he was commissioned to paint a large mural for Rotterdam City Hall in 1923, he had better luck earning a salary with when he managed to get two of his novels published in 1938, his most successful being The Tragedy of the Dream, a biography of the painter Matthijs Maris. Arondeus’s own dreams of artistic and personal freedom would come to an end with the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands in 1940. Hitler’s doctrine of oppression and abuse of minorities had included homosexuality since the party’s rise to power in 1933, and by 1940, more than 100,000 gay men had been sent to concentration camps and been made to wear a pink triangle as identification of their sexuality.

In no doubt of his and others’ fate at the hands of the Nazis, Arondeus first published the underground resistance paper Brandarisbrief and then formed the Raad van Verzet (Resistance Council) with other artists. At this time, he would meet Frieda Belinfante, a cellist, conductor, and a gay Jewish woman.

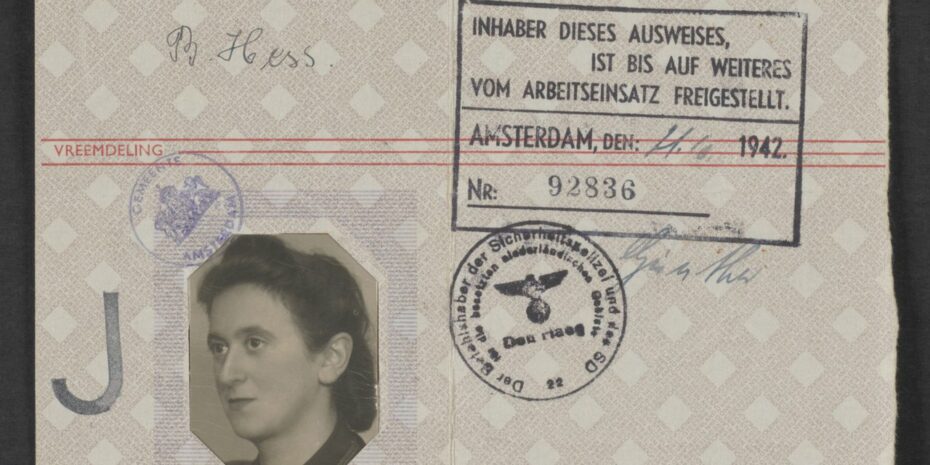

Frieda had become the youngest woman in Europe to lead an orchestra at that time. By 1941, she had put away her cello to conduct a campaign of resistance and defiance against the Nazi oppressors. Using their artistic talents, the group set to work producing forged documents for Jews and others who were wanted by the Gestapo. Their first problem was that the Dutch identity cards were some of the hardest to counterfeit in Europe. By trial and error and sheer will and audacity (and a rather large financial contribution by Harry Heineken the prominent Dutch brewery owner), they succeeded in producing adequate counterfeit papers using a printing press. They managed to produce around 70,000 false papers that helped to hide the hunted and persecuted.

Problems started to arise when the Nazis began to check the corresponding duplicates in the records office. Arondeus and the others in the resistance movement realised the records office would have to be destroyed or all their work would be in vain. So one night in 1943, they managed to break in to Amsterdam’s civil registry office and destroy more than 50% of the records, around 800,000 documents, saving thousands of lives in the process.

The Partisans would go into hiding but were eventually betrayed and caugh. Arondeus and his comrades were sentenced to death, despite his defiant attempts to take all the blame for planning the sabotage and steer the punishment away from the younger members of the resistance. Of the 15 caught, 12 would be executed by firing squad, Arondeus included. Frieda Belinfante would be the only member of the resistance to escape and survive by living in disguise as a man for the remainder of the war.

The Nazis considered homosexuality to be a threat to their idea of Aryan supremacy and sought to eradicate it. But the brutal treatment of the LGBTQ community is so often treated as an afterthought in the context of re-telling World War II history. And let us not forget, in the Allied countries, such as the United Kingdom and the United States, homosexuality wasn’t decriminalised until well after the war in the 1960s and the military actively sought to identify and remove gay soldiers, viewing their sexual orientation as a threat to morale and discipline.

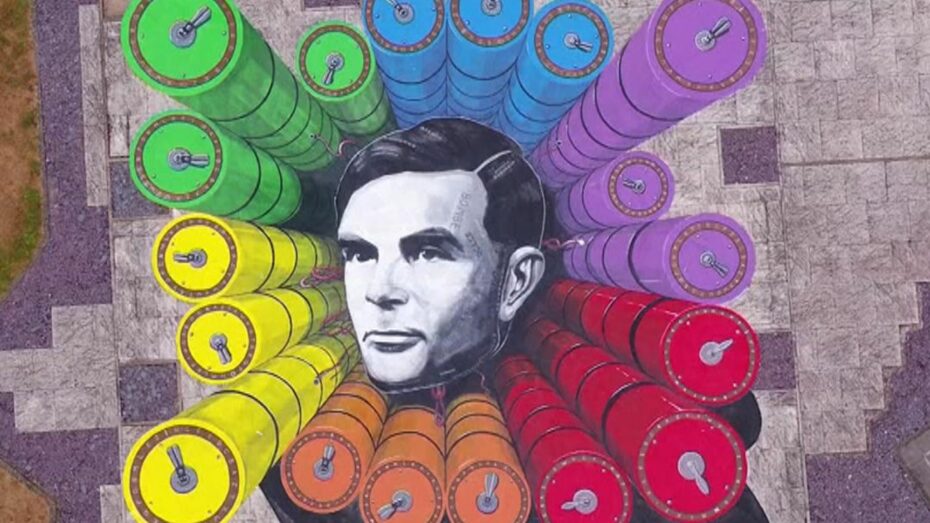

Alan Turing was a British mathematician and cryptographer, who would go on to be recognised as the founding developer of the first modern computer and artificial intelligence. He would also be instrumental in cracking the ‘Enigma machine’, the highly sophisticated electromechanical Cipher encoder used by the Nazis to transmit messages during the war. Thanks to Turing and his team, this information ultimately turned the tide of the war. But not only would Turing’s vital work and legacy go unrecognised for decades, he would actually be persecuted for his sexuality in his home country. Having kept his personal life hidden from society, he was outed and prosecuted for gross indecency in 1952 for an affair with a man. His punishment by the draconian laws of the day was chemical castration. Two years later, Turing would bite into an apple poisoned with cyanide, ending his life. It wasn’t until 2009, that British Prime Minister Gordon Brown would posthumously pardon Turing and issue a public apology:

“We’re sorry — you deserved so much better Alan and the many thousands of other gay men who were convicted, as he was, under homophobic laws.”

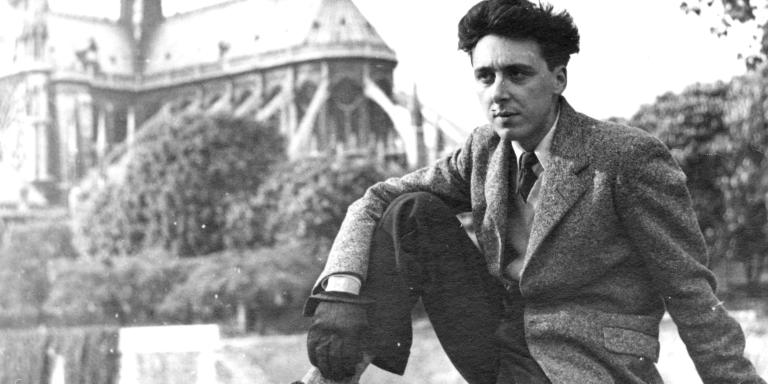

Then there was Daniel Cordier, who spent the war in occupied France working with Jean Moulin, a well-remembered hero of the French resistance, organising a massive network of rebellion against the Nazis while trying to remain two steps ahead of the Gestapo. A recipient of the Légion d’Honneur, it wasn’t until 2009 that Cordier would talk about his sexuality. “Even if I have never hidden from it, I have never spoken about it, because these are difficult things to write about, especially for a man of my generation.”

Isabell Pell, an American socialite, occasional actress, and French resistance fighter had found herself in France after a rather public and scandalous affair with a female opera singer. Moving to Paris to escape the attention judgemental society of the time, Pell and others lived a more open and exploratory existence until the invasion of France by the Nazis. Changing her name to “Fredericka”, Pell played an active role in the French resistance before being captured by the Italian army and sent to a concentration camp and integrated. She managed to escape however, and fled to a forest with her lover Claire Charles-Roux De Forbi where she became instrumental in the communications between the resistance and the Allies. In 1944, Pell helped save a troop of Americans surrounded by the Nazis in the French town of Tanaron, leading them to safety and later joined the American 1st Airborne Task Force led by Major General Robert T. Frederick. She would later be awarded Légion d’Honneur for her bravery and guile.

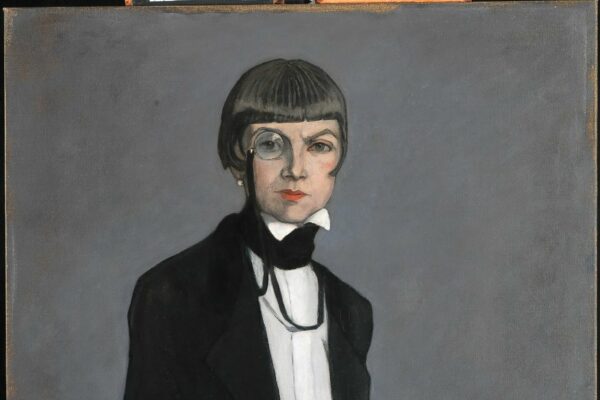

As a largely unknown early pioneer of queer culture, Claude Cahun would wage a creative misinformation war against an occupying force of Nazis on the island of Jersey during Wor found later notoriety with Dior and David Bowie, who cited them as an influence, but she is also deserving of recognition for some seriously brave actions when Hitler’s army threatened to change the face of Europe. Born Lucy Renée Mathilde Schwobin in France to a prosperous and influential Jewish family, Cahun had shed their given name as they explored the preconceived ideas of sexual identity while finding a career acting in plays and producing surrealist photography and art.

In 1937 when anti-Semitism and the Nazis fascist doctrine were on the rise, Cahun and their partner Marcel Moore escaped to Jersey, only to be followed by the Nazis when they invaded the island too. Over the next years, they would conduct a secret campaign of subversive resistance against the island’s occupiers, eventually resulting in their capture and incarceration by the Germans. They would both receive death sentences for their defiance but before the punishment could be carried out, the war ended. Their story would remain hidden until the 1990s when the biography Claude Cahun: Mask and Metamorphoses by François Leperlier was published.

There are countless more names, but where is their monument, their moment of silence, their narrative in Hollywood wartime epics? These heroes lived most of their lives in the shadows, in a climate of secrecy and fear, hiding their true identities even at home, when the tangible enemy had retreated. For the close-minded, they are still an inconvenient reminder that being LGBTQ+ isn’t a millennial phase or a Generation Z fad. People have always been queer. We aren’t seeing a sudden increase, we’re just seeing how many people were once silenced.