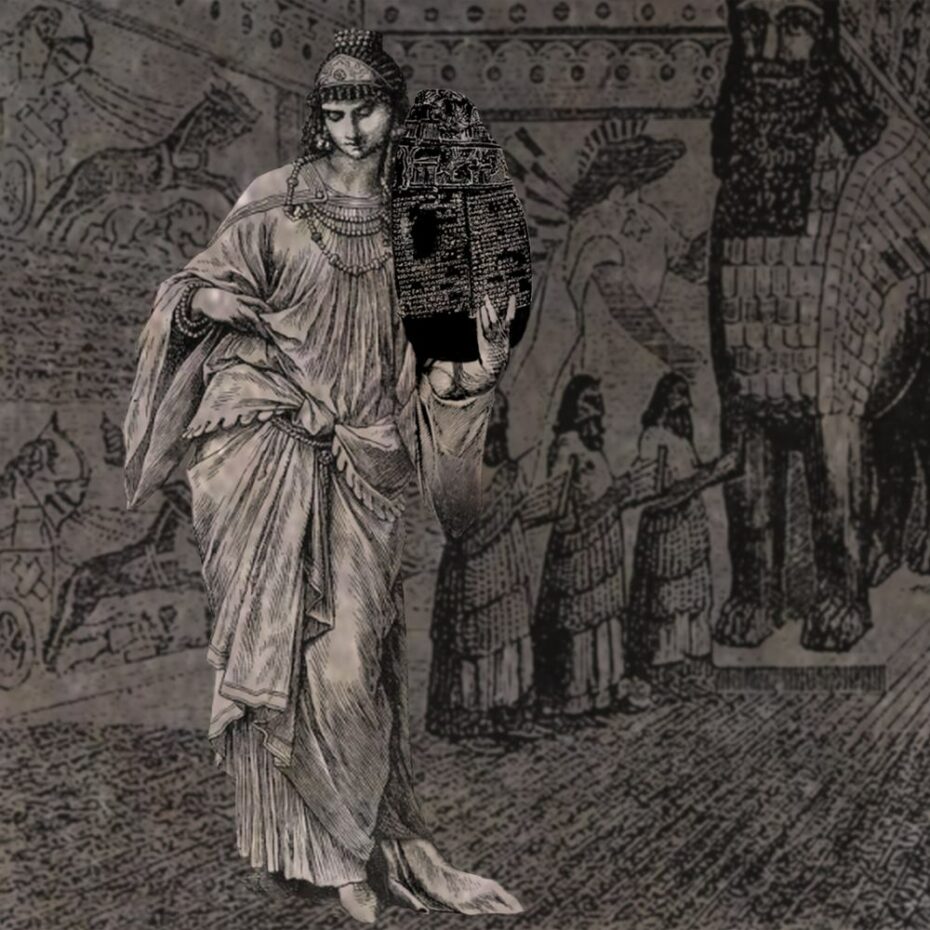

The first-known public museum opened over 2,500 years ago – and it was curated by a woman. Her name was Ennigaldi-Nanna. She was a priestess and princess, the daughter of Nabonidus, the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, who was also an antiquarian and known as the first serious archaeologist in history. Encouraged by her father, Ennigaldi opened her palatial antiquity museum during the Neo-Babylonian Empire around 530 BCE, located in the state of Ur (modern-day Iraq). It contained her own curation of artifacts dating as far back as 2000 BCE, many of which she is thought to have excavated herself in southern Mesopotamian. When her neatly arranged educational displays were unearthed by archaeologists more than two millennia later in 1925, one can imagine the utter bemusement of discovering ancient history that was also discovering its own even more ancient history.

When husband and wife archaeologists Leanard Woolley and Katharine Woolley excavated portions of the palace and temple complex of Ur in 1925, which lead to discover Ennigaldi-Nanna’s museum, it was an unprecedented discovery within a discovery. In 1925, the Woolleys knew they were excavating a Sumerian site that existed in 500 BCE but Ennigaldi’s museum of much older artifacts filled in major historical gaps about an era that had no previous record. To Ennigaldi, those artifacts were nearly as old then as her own civilisation is now to us, and thanks to her initiative to uncover and document the past, a missing piece of humanity’s timeline is not lost to the annals of history.

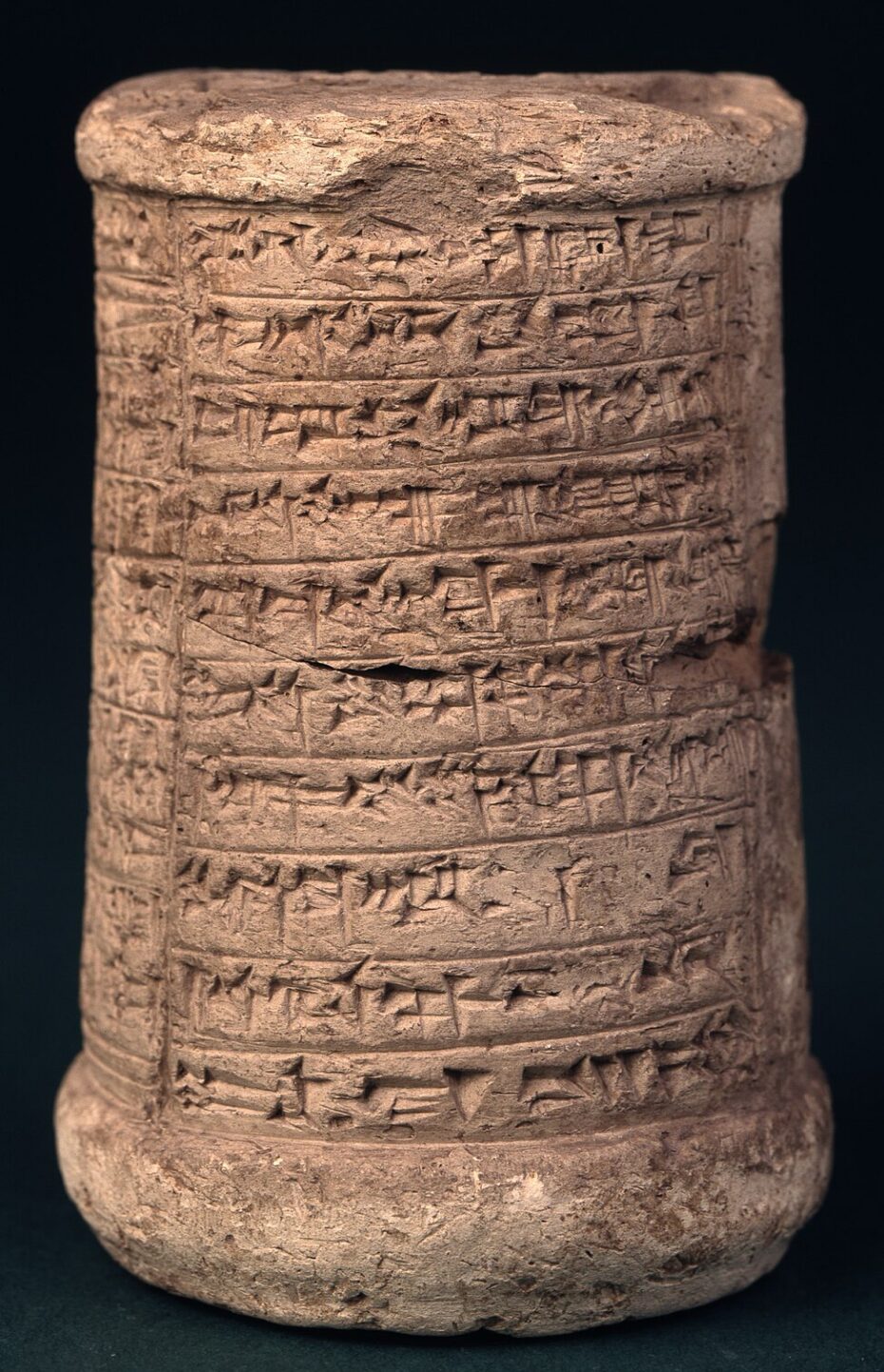

The collection displayed objects such as writing tablets, jewellery, and carved statues which were arranged in a very specific order to help the visiting public follow the timeline and story of a civilization. The objects were accompanied by “museum labels” made of clay drums, written in three languages including Sumerian, and provided information about the object’s age, origin, and significance. The categorisation of her objects were unique for her time and for many centuries after her.

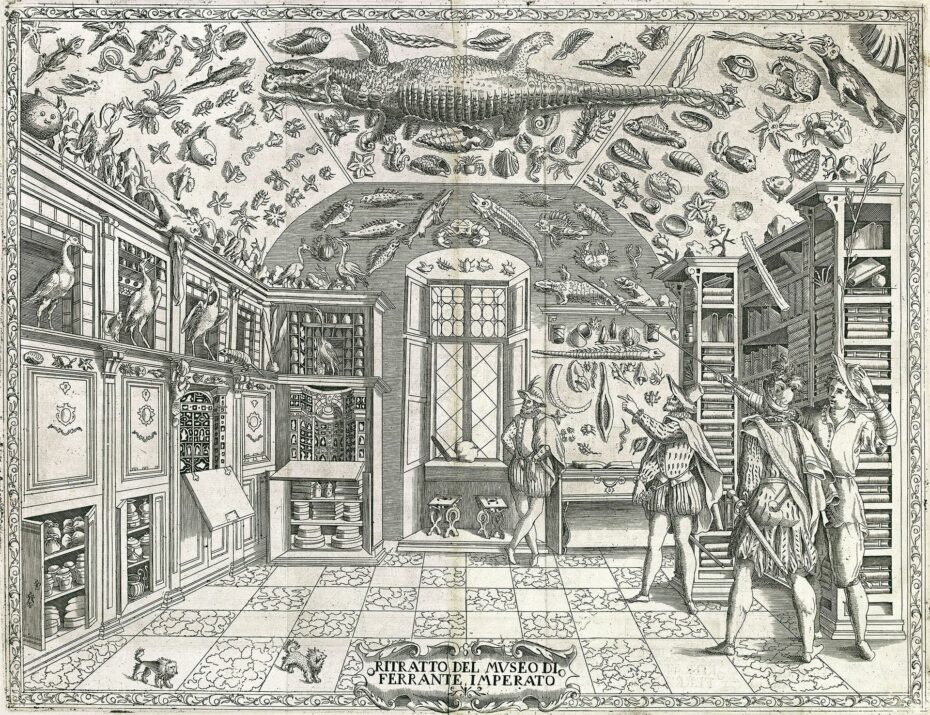

For thousands of years following the eventual collapse of the Sumerian kingdom which saw the end of Ennigaldi-Nanna’s museum, objects of curiosity, beauty, or general interest were largely collected privately in curio cabinets or kept in religious institutions. Rarely were the objects in these collections displayed in an educational manner, and were certainly not labeled. In fact, often times curio cabinets or private collections took an artistic and aesthetic approach to displaying objects. Imaginative specimens of flora and fauna from different specimens might be stitched together to create fantastical creatures.

Art and historical collections remained as private collections until 1683, when Elias Ashmole took the art collection catalog of John Tradescant, described as ‘musaeum Tradescantianum’ and had it transferred to a new building in Oxford university built for the purpose of housing the collection. When opened to the public it became the first modern museum, called the Ashmolean Museum. Labelling and classifying each object to provide context and information for visitors as Ennigaldi-Nanna had, only became common practice in modern museums as they were popularized in the late 19th century and onward.

In addition to her work as the first museum curator and possibly the first female archaeologist, findings indicate that Ennigaldi-Nanna also ran a school for women of the elite society of her time within the temple complex at Ur. It’s very likely she also lived on the same site as the museum, within the palace grounds. In a domain that was and has remained for millennia a primarily male occupation, Ennigaldi ran the show.

She was a pioneer before her time and her museum was significant not only for its role in preserving and displaying ancient artifacts that would likely have been destroyed over time, but also for its contribution to the development of modern museum practices. Today, many of the artifacts from the Ennigaldi-Nanna’s collection are now housed in the British Museum in London.

We all have something to contribute to the beautiful patchwork of our history and can never know how our pursued interests can help preserve pieces of history that would otherwise be lost to time without our interest in them. Prehistory is the time before written records, the period of human history we know the least about, but it’s also the longest by far, including the Bronze Age and stretching from 900,000 years ago until the Roman invasion in AD 43. There are countless holes in the tapestry of our historical literacy for which we need the needle and thread of historical figures like Ennigaldi-Nanna and her museum to reveal answers.