by Richard Avedon

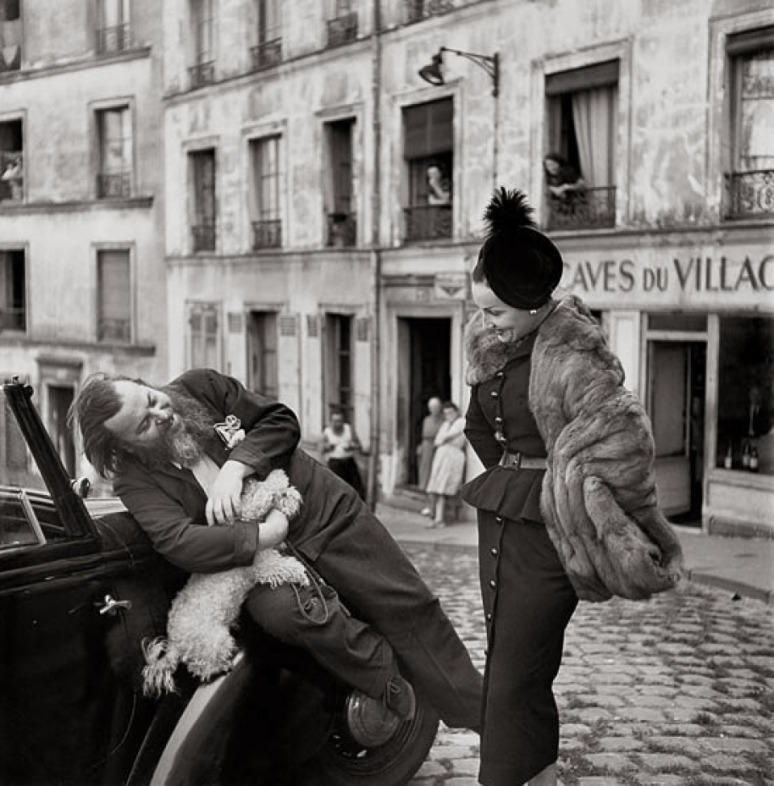

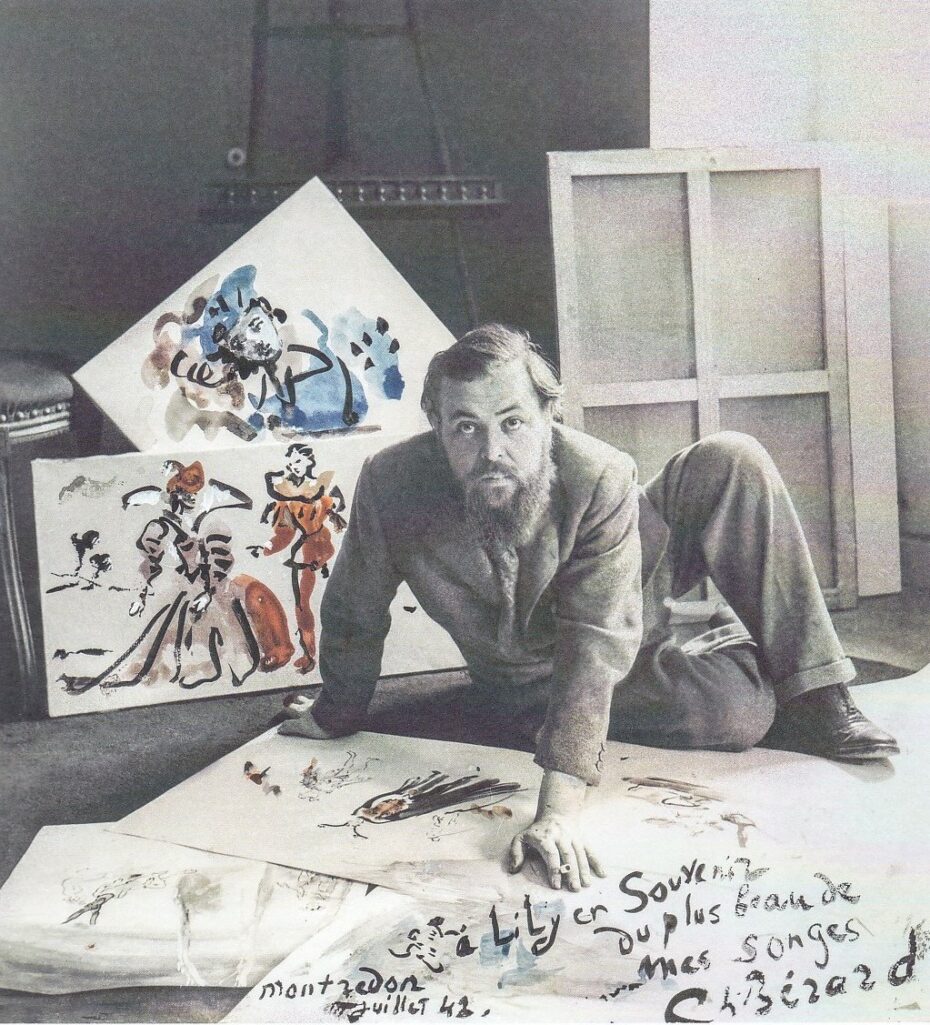

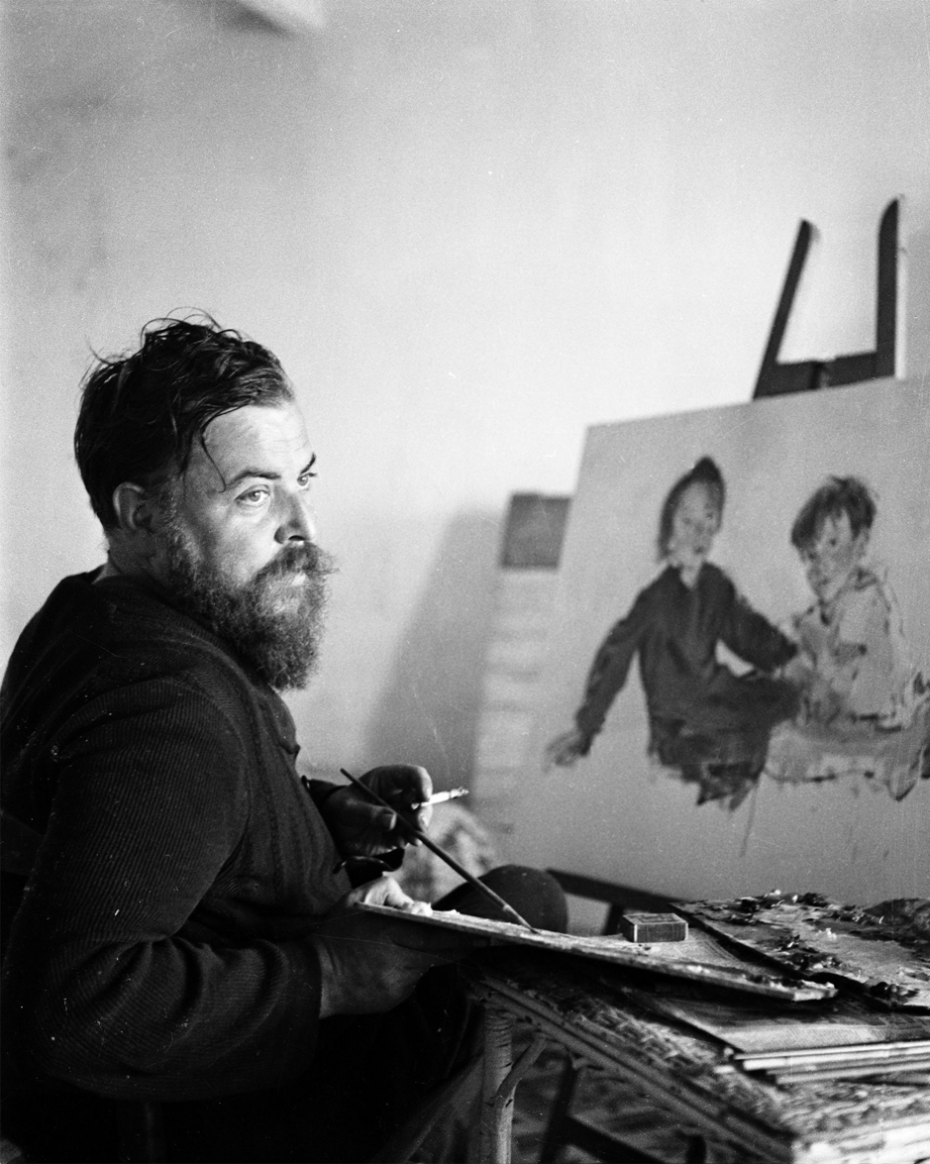

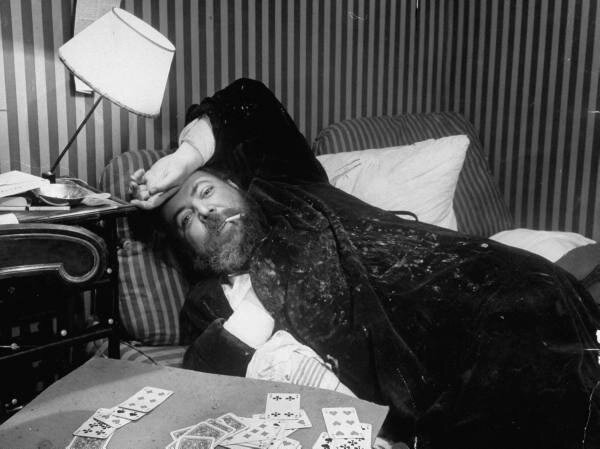

Fabulous, free and fashionable, France bloomed in the 1930s. The avant-garde arts flourished, Paris was at the centre of it all and her output was bountiful. The creative giants of the day, Picasso, Cocteau, Coco Chanel, May Ray, Beauvoir and Sartre, the Lost Generation and their cultural circle basked in a warm summer evening’s glow of new culture and liberalism. But there’s one name that was very much a part of this moment, who you must meet. Bébé, aka, Christian Bérard. A handsome, burly and intentionally unkempt man sporting a wild woolly beard with loveable puppy dog eyes, he accessorised with that essential designer cigarette teetering at the corner of his mouth and dressed his robust frame in a stained, crumpled painter’s overall. Bérard and his lover Boris Kochno were one of the most prominent openly homosexual couples in Paris during the 30s and 40s. Bébé was the nickname given to Christian Bérard by his friend, the French prophet of the arts, Jean Cocteau, on account of his delightful babyface – and the name stuck. Famously dishevelled, “The Magnificent Tramp” or Clochard Magnifique (also the title of his biography) was frequently flanked by his beloved fluffy white dog, allegedly often as paint-stained as its owner. A supremely talented, industrious and capable artist, a wild socialite and extrovert, Bébé was a Parisian sensation. Let us introduce you …

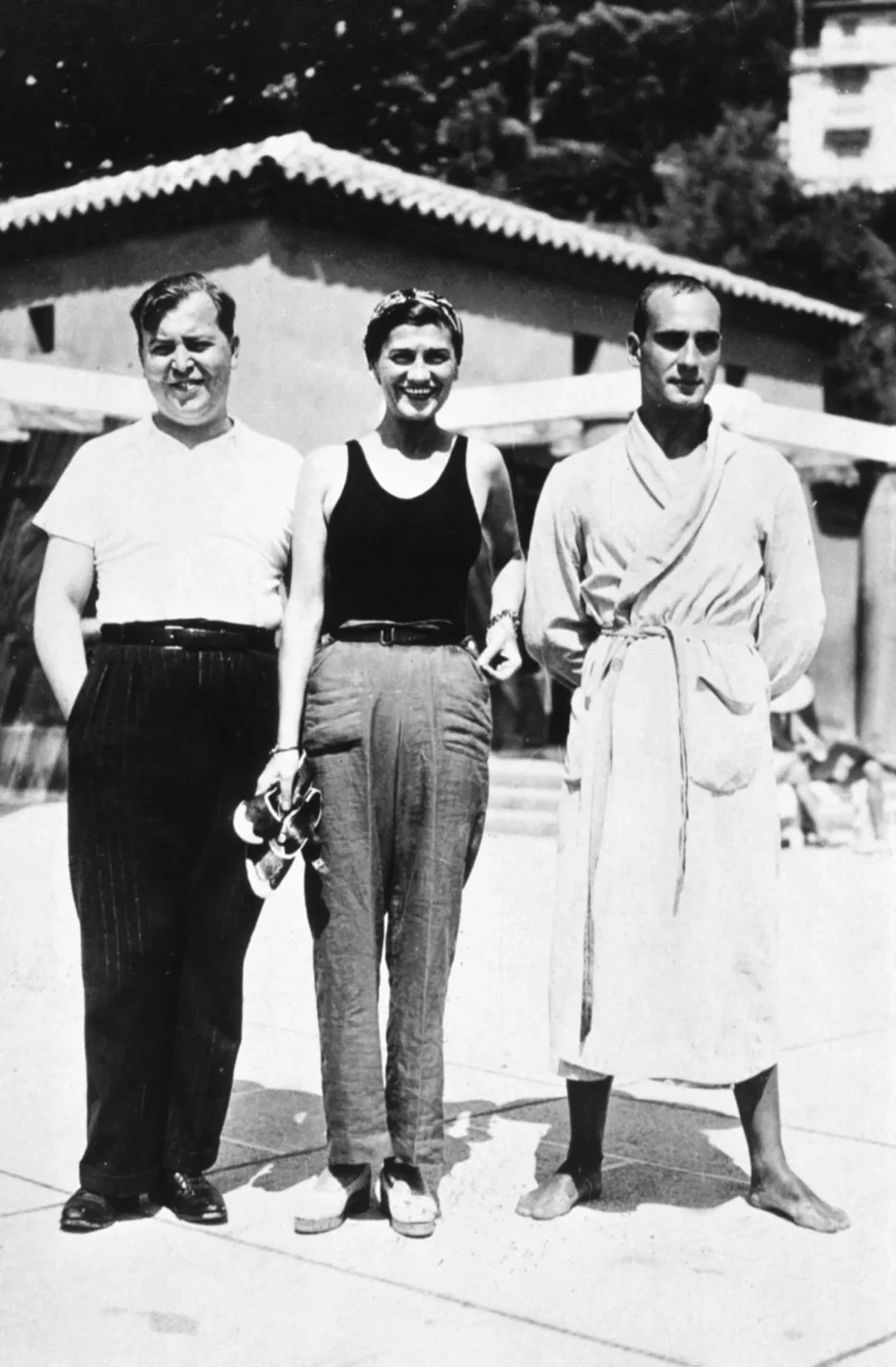

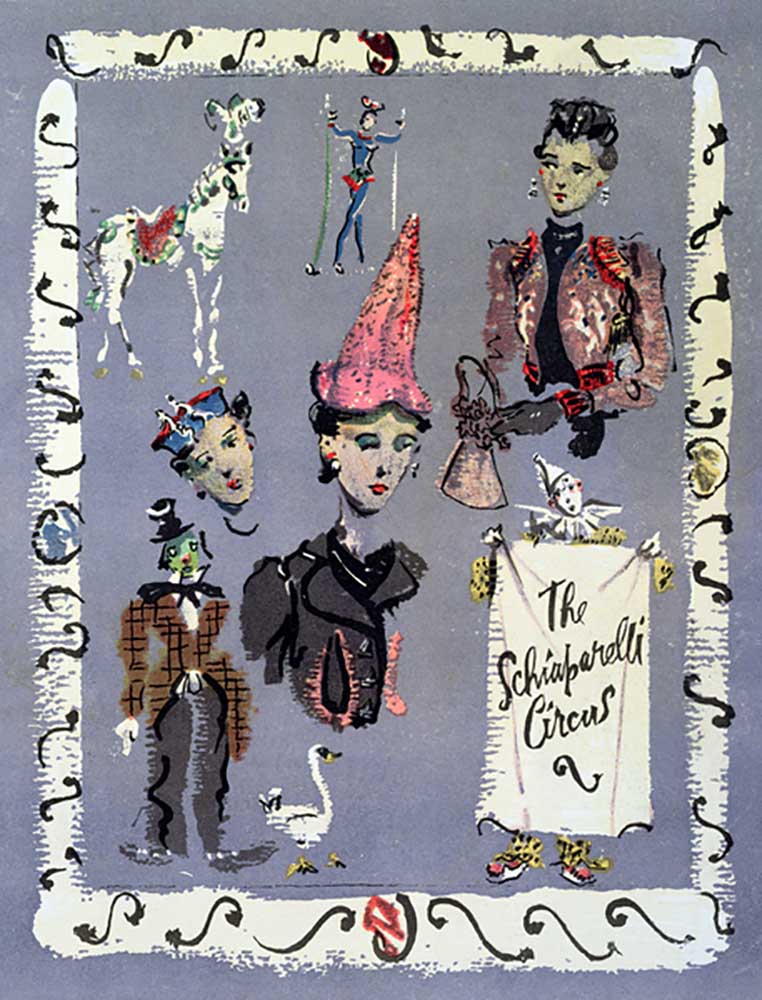

Bébé capered and cavorted with the great and the good, between Paris and London, he was a fixture and friendly face at every high society party and gathering of the 1930s. Holiday companion to the superstar designers and artists, he counted Christian Dior, Jean Cocteau, Coco Chanel, Elsa Schiapparelli, Colette and Yves St Laurent among his close friends.

A longtime lover of Bébé, Boris Kochno was a Russian poet, dancer and Francophile who fled Soviet intolerance and would be a founder of the Ballets des Champs-Élysées in Paris. Together they were the most enviable and elegant gay couple of the 30s and had all of Paris and beyond eating out of their hands. He lovingly recounted their long romantic walks through Paris after dark and remembered how Bébé was so relaxed and playful away from the easel, but would design, draw and paint with a fervour and focus, as if driven by an unseen force.

Bérard was a fashion illustrator extraordinaire. In his diaries, Bébé longtime friend Cecil Beaton recalls watching Bébés creative process…

“This morning Bébé painted like someone in the throes of mediaeval torture. He did not talk during the sitting. He groaned, whispered, sighed, whimpered, stamped his feet, jerked backwards and forwards, lunged with noisy intakes of breath. ‘ You don’t know how difficult it is! Oh God, oh God! Ah, je vois. Non, ce n’est pas ca! O. Dieu!’ It was both a revelation and a lesson to me. Bébé’s work is the result of acute concentration, making even so lightly painted a portrait as mine a tribute to agony. After a long bout, he rested to smoke a pipe. I said, ‘I’m so sorry you have suffered as you did today.’ He replied, ‘It’s all I like in the world!'”

Cecil Beaton

Born in 1902 of a rich and creative artistic vein, Christian’s father, André Bérard, was regarded as the official architect of the city of Paris of the day. From his early childhood, Christian had had the urge to raid his mother’s fashion magazines and copy the drawings – this ignited a passion and ability for him to be able to immediately capture the essence of costume on paper, which stayed with him throughout his life.

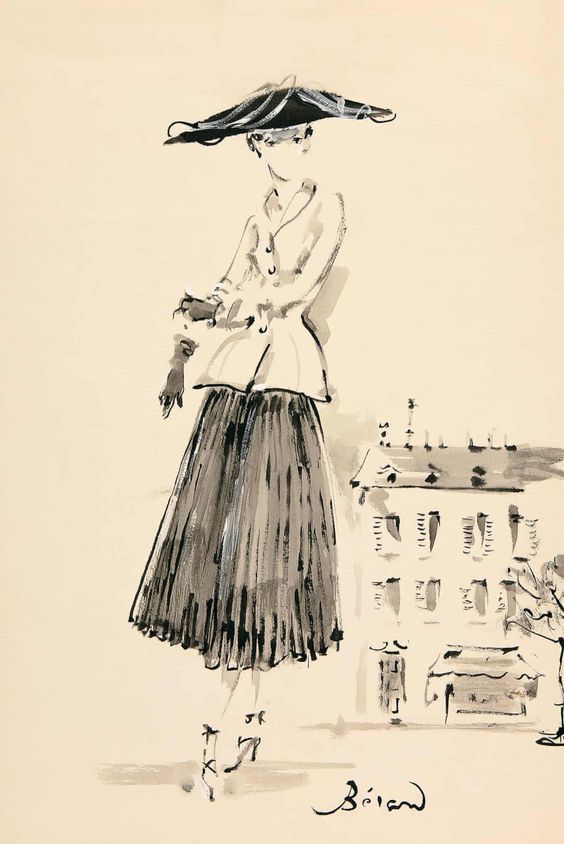

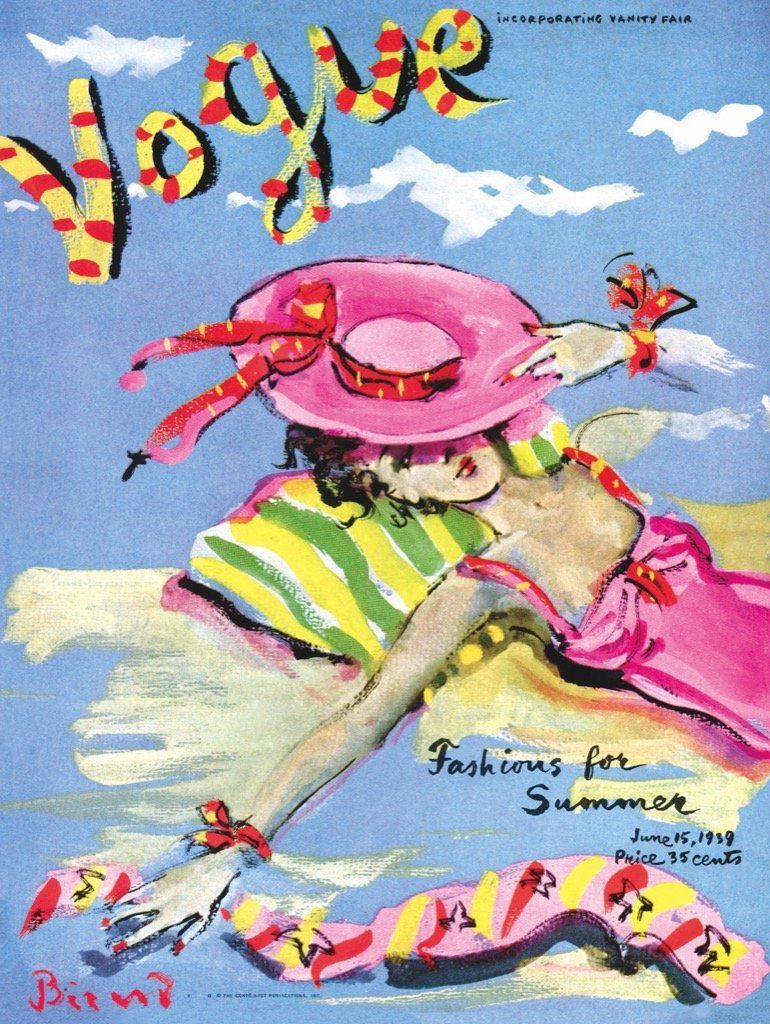

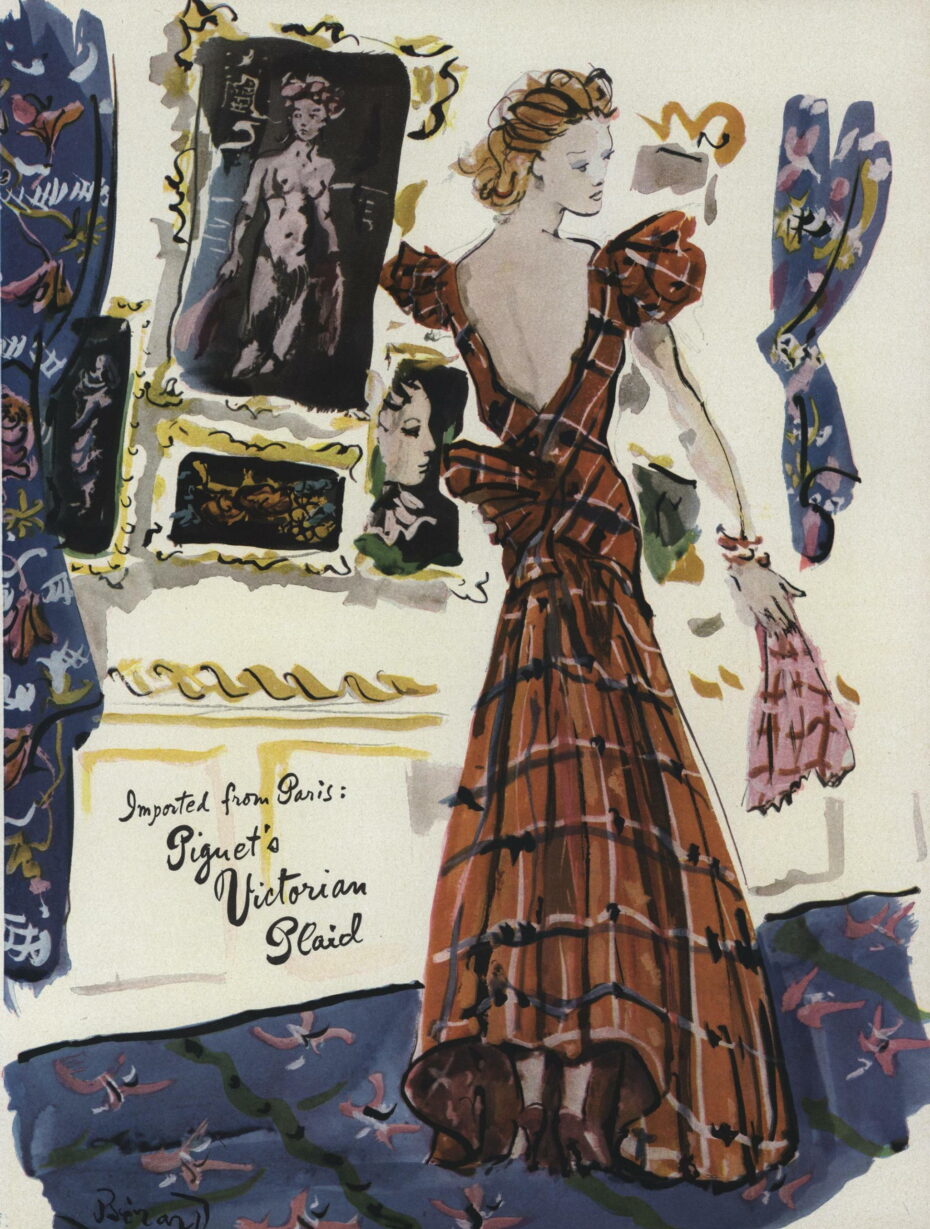

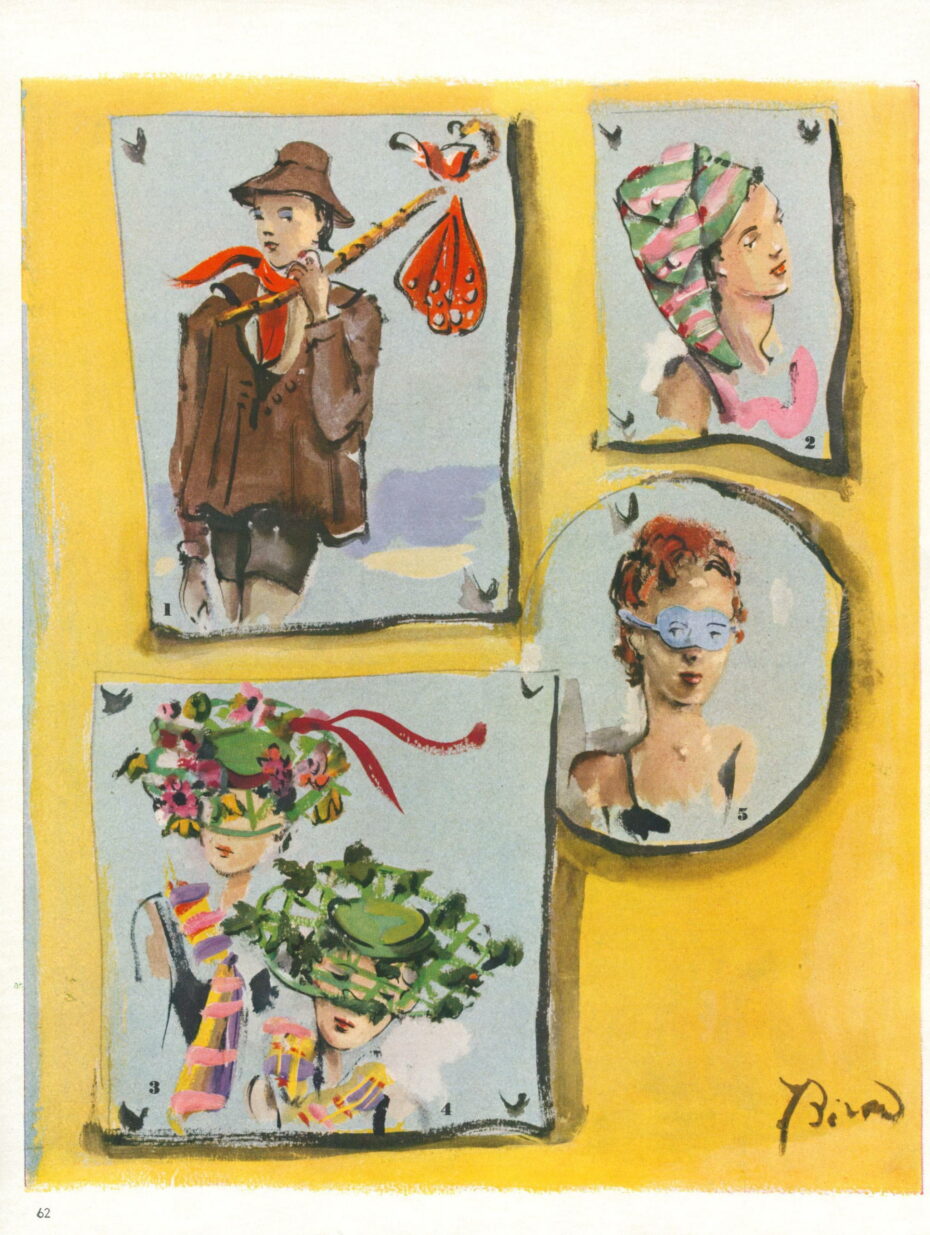

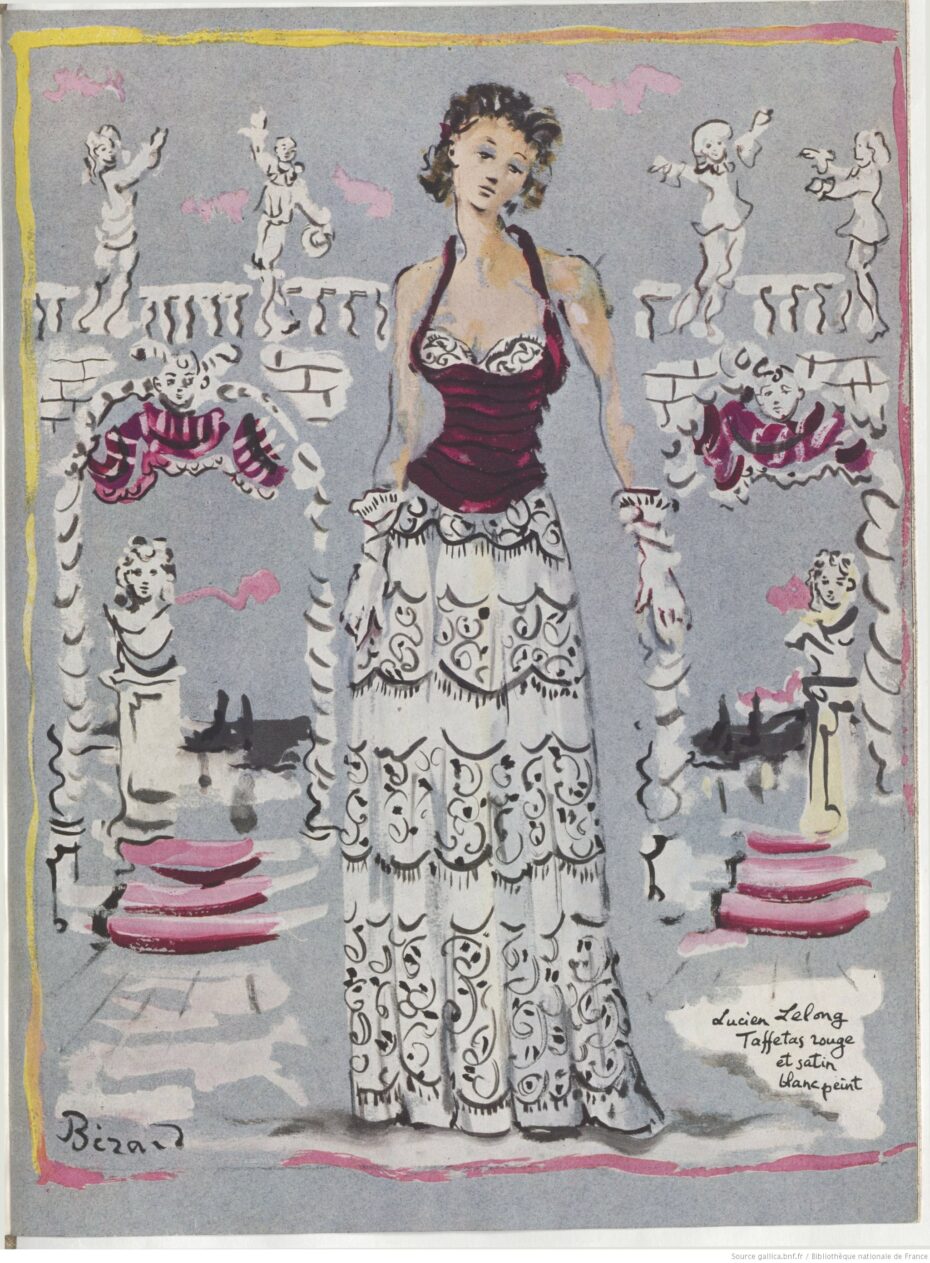

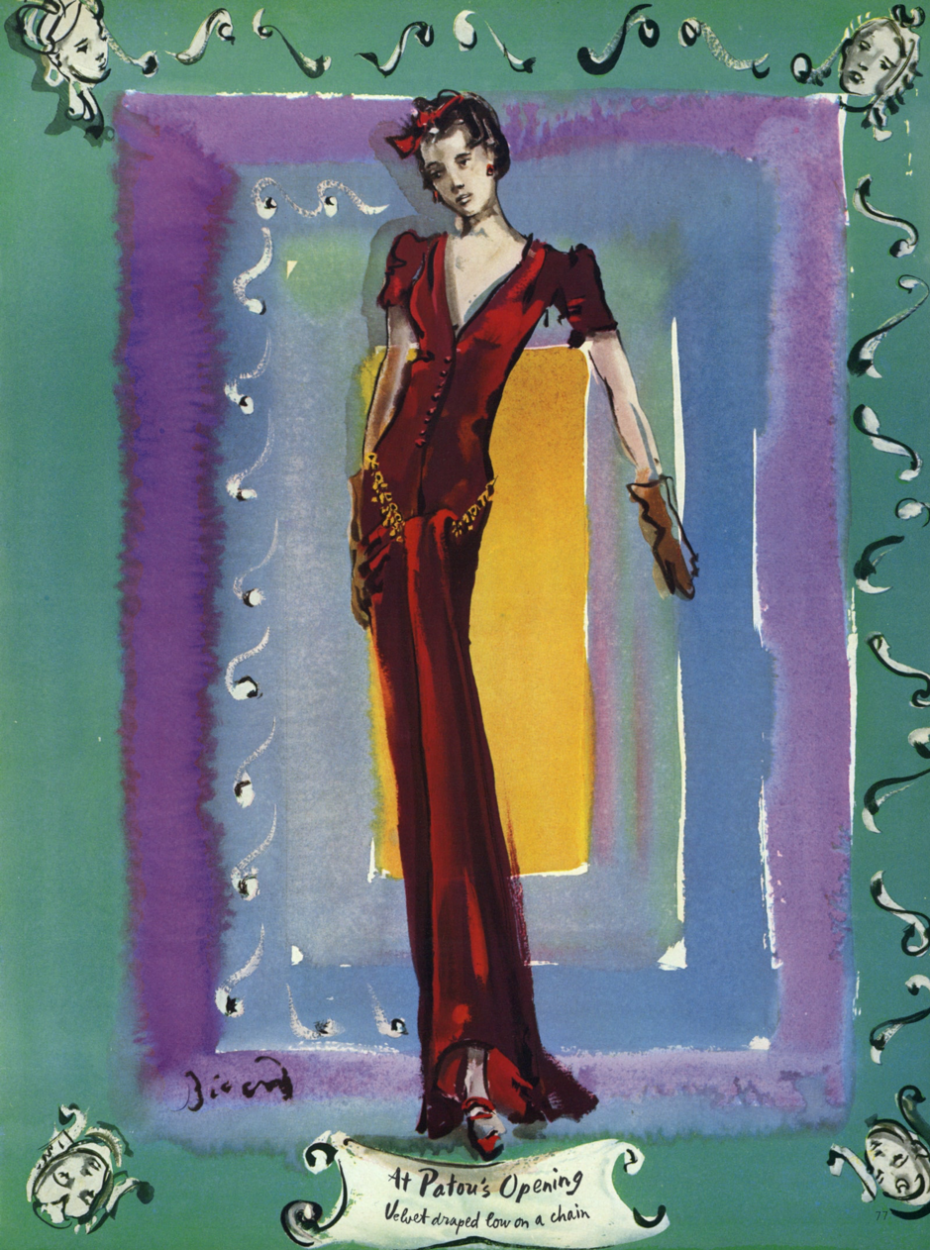

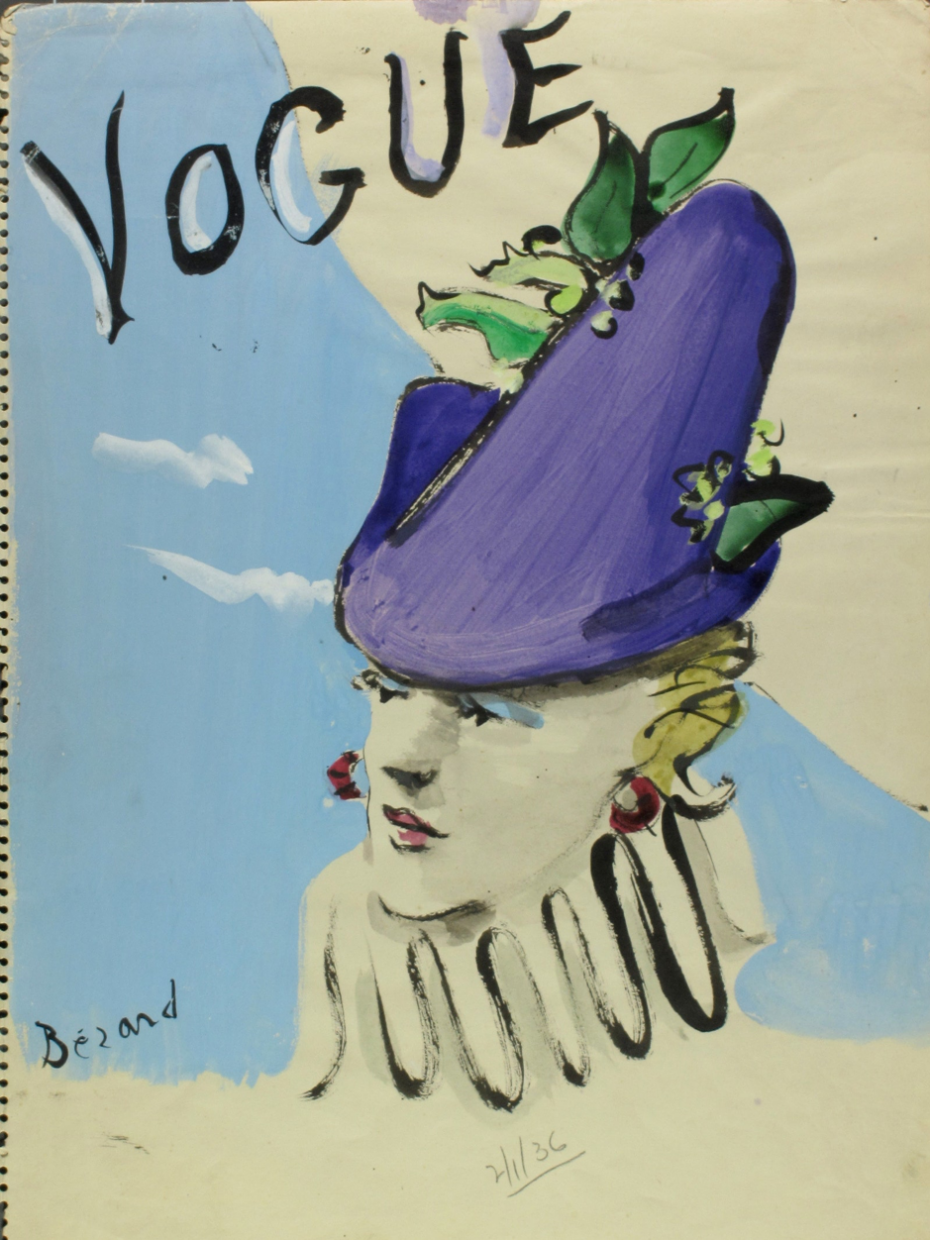

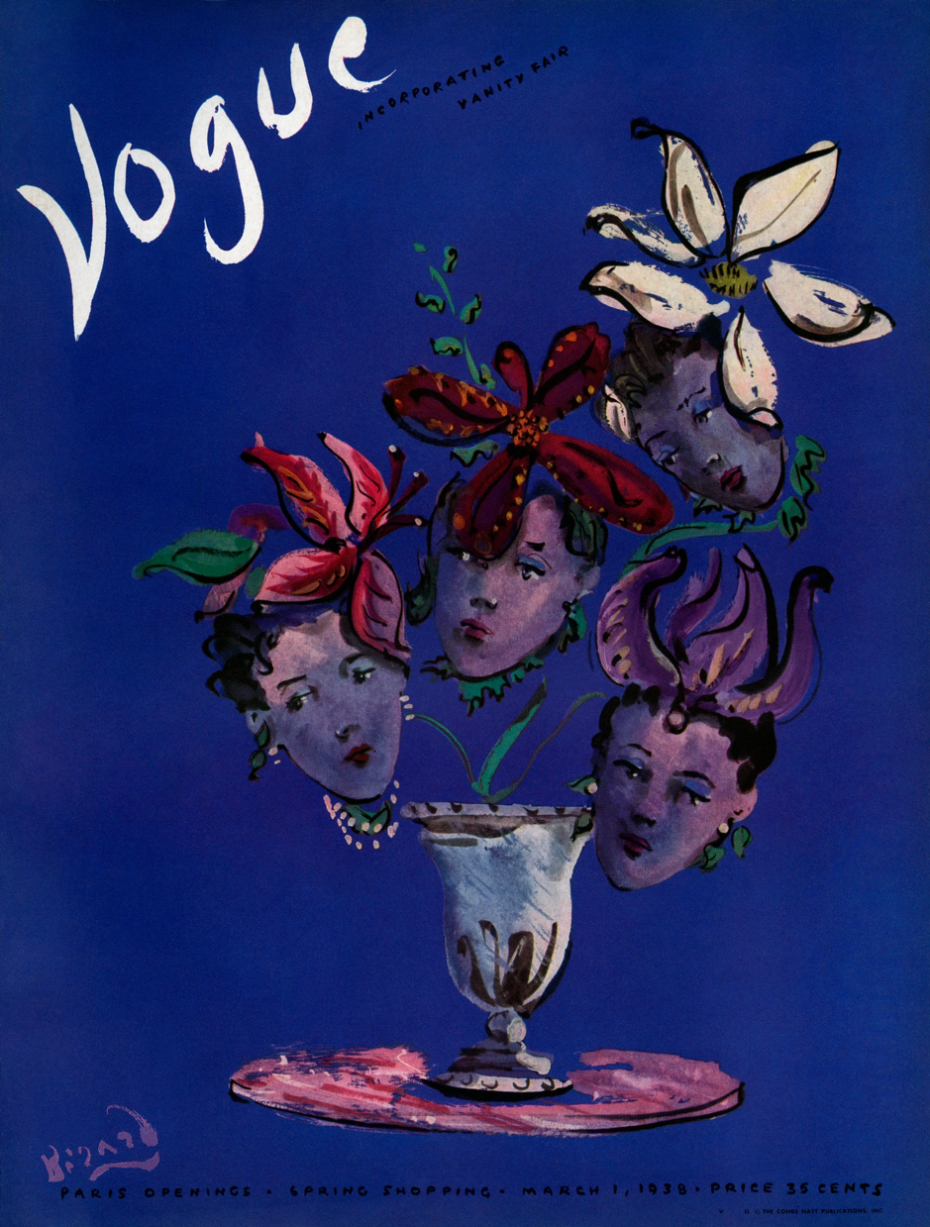

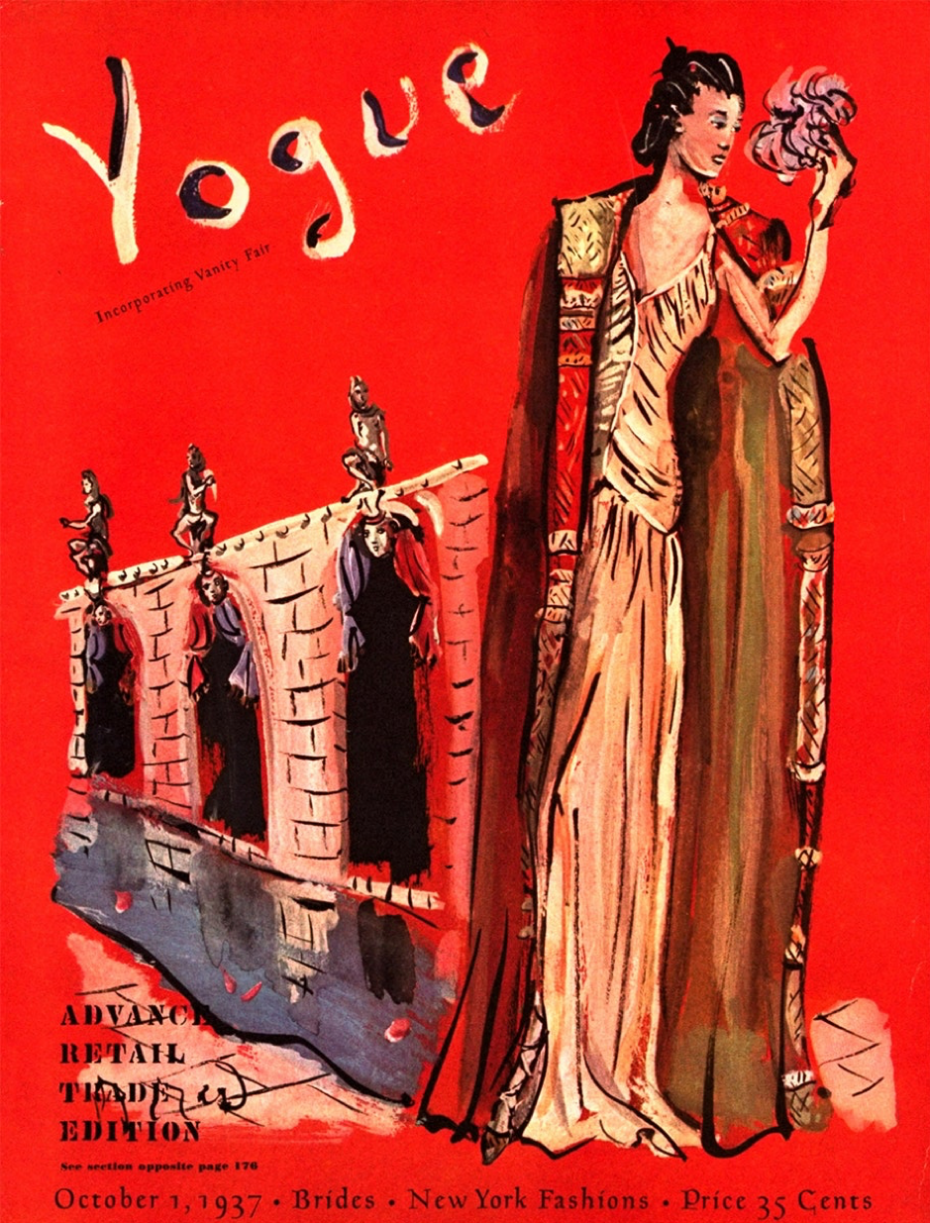

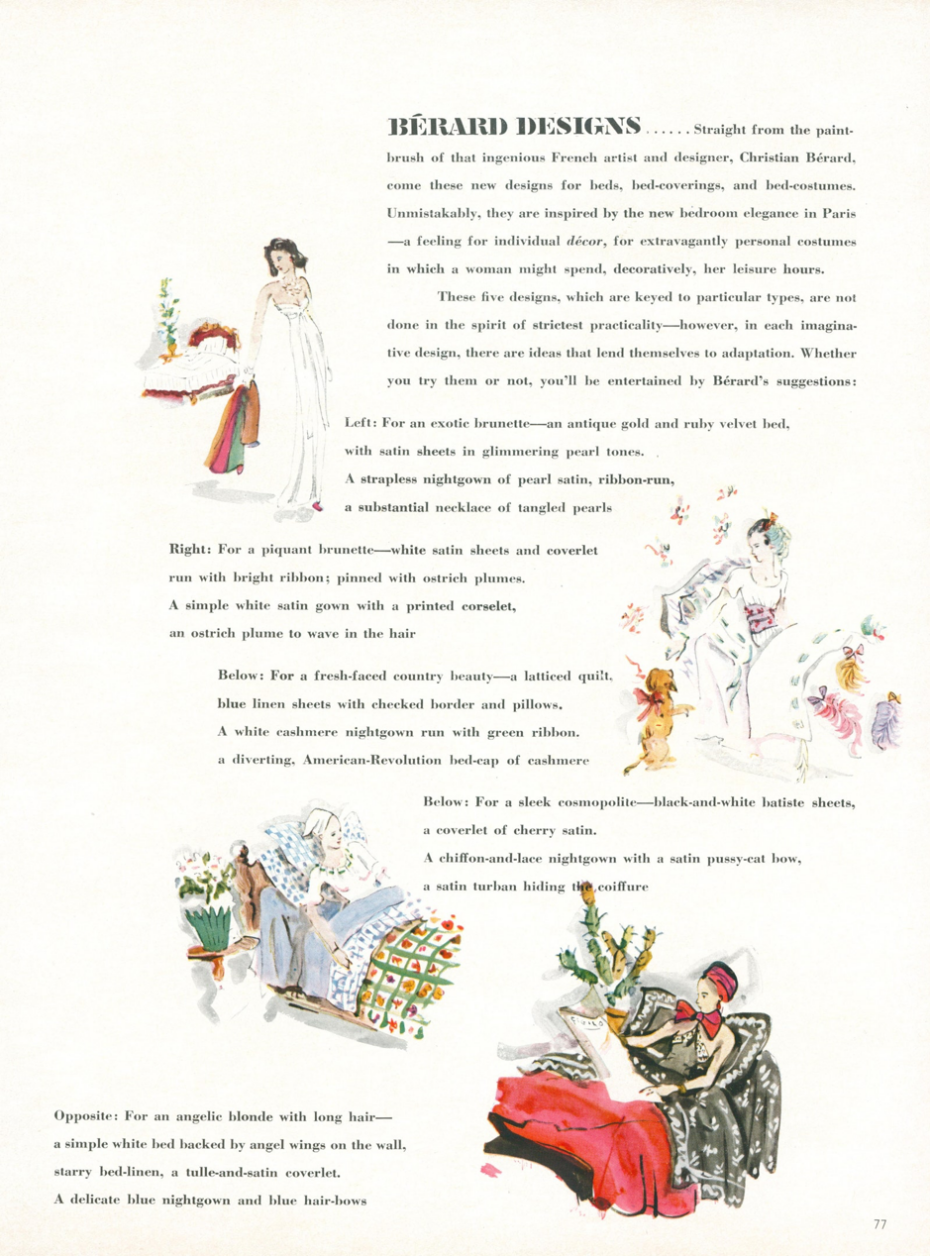

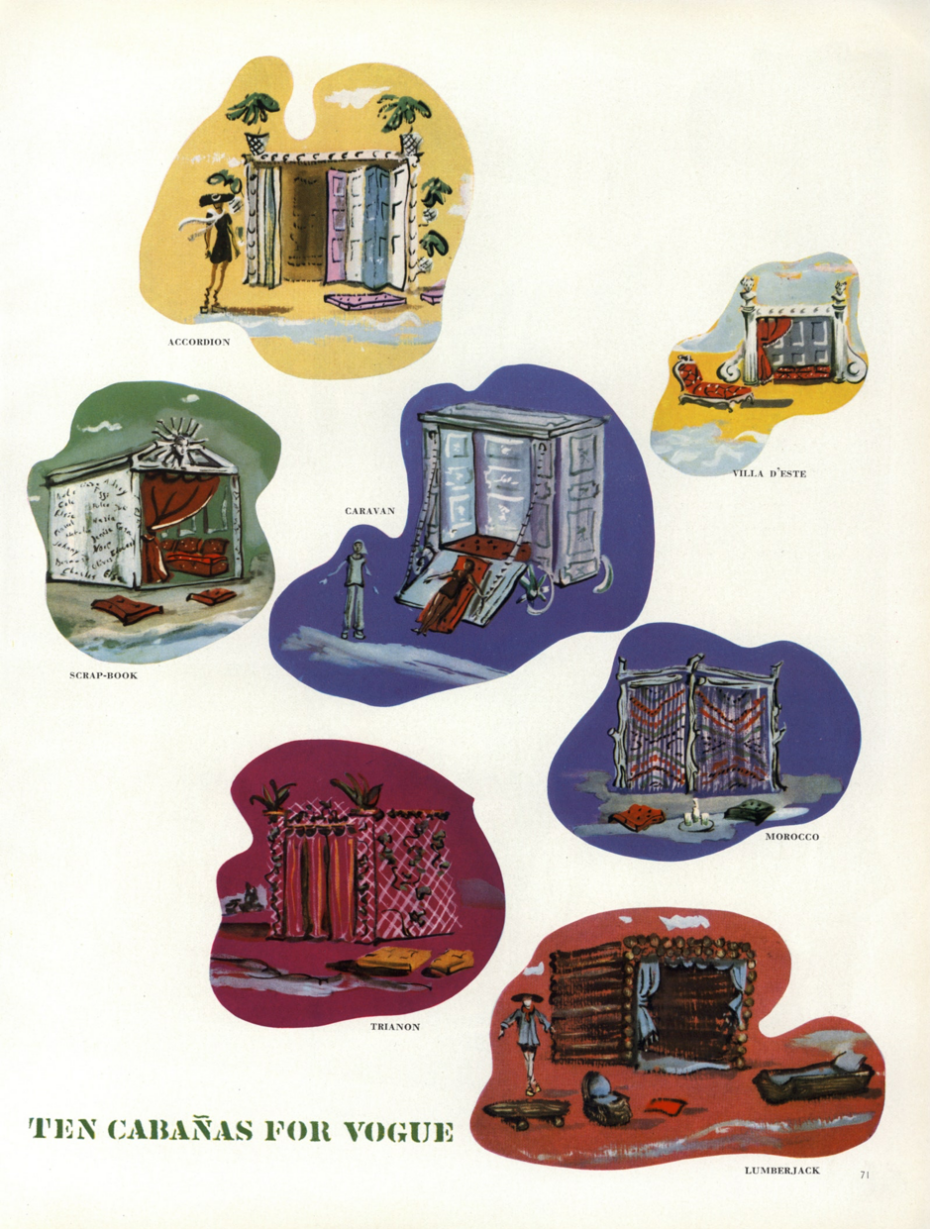

This creative duality of painting and fashion blossomed in the mid 20s with his costume design for the ballet Les Elves in 1924 and with his first painting exhibition held at the legendary Gallery Pierre in 1925. Bébé’s vivacious creations, larger-than-life personality and exotic social circle bestowed an added dimension to the high-brow publications Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and Art et Style. Gertrude Stein collected his early paintings and his work often inspired the couture collections of designers like Christian Dior, Schiaparelli and Nina Ricci.

Whether stage sets, costumes, posters or portraits, Bébe’s ideas and techniques triumphed. In the entertainment world, one of the few shadow workers to come out of the shadows.Through his theatrical design successes he met the legendary Jean Cocteau, already a deity in French culture and a man with whom he would have both an enduring professional and very personal relationship. Christian curated the uber-glamorous set designs and costumes for Jean Cocteau’s film, the intoxicating romantic masterpiece La Belle et la Bête (Beauty and the Beast, 1946) and eagle-eyed viewers can spot Bébe’s little dog running about in the movie. Jean Cocteau was everything post war France required – poet, playwright, filmmaker, Dada artist and critic, and he too was one of the most openly gay and bisexual men in Bébé’s post-war Paris. It’s believed Cocteau also first introduced Bérard to opium, prompting his addiction.

Bébé’s art and illustration were intensely passionate and had an almost hallucinogenic flavour – as if he was trying to escape this world via his art. From flighty sketches to thickly laid-on oil paint, he exhibited a style that’s still used and emulated by designers to this day. His style was anything but realistic – instead he seemed to have had the curious ability to capture the very essence of a designer’s style and intent in a few scratchy suggestive lines or sweeping dashed dabs of pale colour. This was one-touch art, nothing laboured, pure talent – like few others could (with the exception of Picasso perhaps).

Both the Classical and Rococo movements influenced the compositions, as if he couldn’t let go of tradition altogether. A contemporary touch landed with his unmistakable, nonchalant calligraphy and a flurry of blotchy, squiggly and wispy brush strokes that endeared so many magazine covers.

Director Franco Zeffirelli defined him as “the greatest decorator of his time” and the multi-talented Bébé was equally adept at crafting memorable interior spaces – most notably with French Art Deco genius Jean-Michel Frank. For Frank’s New York apartment, Bébé not only designed the carpets and screens, but painted the murals. This fruitful relationship would unfortunately soon end in tragedy, with Frank committing suicide, unable to cope with an homophobic onslaught.

Christain Bérard unexpectedly died from a heart attack on the 11th of February 1949 while working on the stage at the Théâtre Marigny. A friend and writer, Julien Green, wrote that “Paris drugged him – I’m not thinking of opium, but of success, which is poor quality opium – and finally killed him.” Bérard’s death prompted French pianist Francis Poulenc to compose Stabat Mater (1950) in Bérard’s memory and Jean Cocteau dedicated his 1950s film Orphée to the memory of his friend. The 1960s saw the global explosion of abstract art and new graphic taste and the polite and gentle world of Bébé faded. Only the odd art gallery owner/collector such as Alexandre Lolas still supported his work.

In 2022, a surprise revival of interest in his legacy: the largest collection of his work – the bulk of which belonged to his lover Boris Kochno – was exhibited at the Nouveau Musée National de Monaco by celebrated curator Célia Bernasconi. She attempted to capture the revolutionary essence and the multi-media modernity of Bébé and gave us a snapshot of the man who effortlessly moved between the spheres of fashion, drawing, writing and interior decoration. Bernasconi tells an anecdotal tale of how instrumental Bébé was to a very young Yves Saint Laurent, who saw L’ecole des femmes while on holiday in Algeria (the set and costumes designed by Bébé). The young boy built himself a paper theatre and proceeded to imitate the drawings of Bébé. (These drawings by Yves Saint Laurent were also on show in Monaco.)

A visionary and dreamer, Christian Bérard’s talent and infectious personality lit up Paris and his effortlessly scribbled and dabbed brushwork continues to influence young designers today. But now we also have another name to add that imaginary guest list for our dream dinner party. Let’s make some room for Bébé, he would no doubt be the life of the party.