Nothing says old-world luxury quite like the Orient Express. The train of kings, courtesans, spies, storytellers and murderers alike, all elegantly dressed and sipping on Champagne from cut-glass crystal flutes as European landscapes rolled by. The Orient Express, which linked Paris to Istanbul, connecting Europe to Asia on an 81-hour ride operating between 1883 and 1977, didn’t just have an impressive guest list, it also changed the course of history, quite literally, when the armistice was signed in dining carriage 2419D on 11 November 1918, ending World War I. As we approach the 150th anniversary marking the inauguration of the Orient Express, the iconic service is set to make a spectacular comeback, and its journey back to the tracks has been a wild ride that merits a novel of its own.

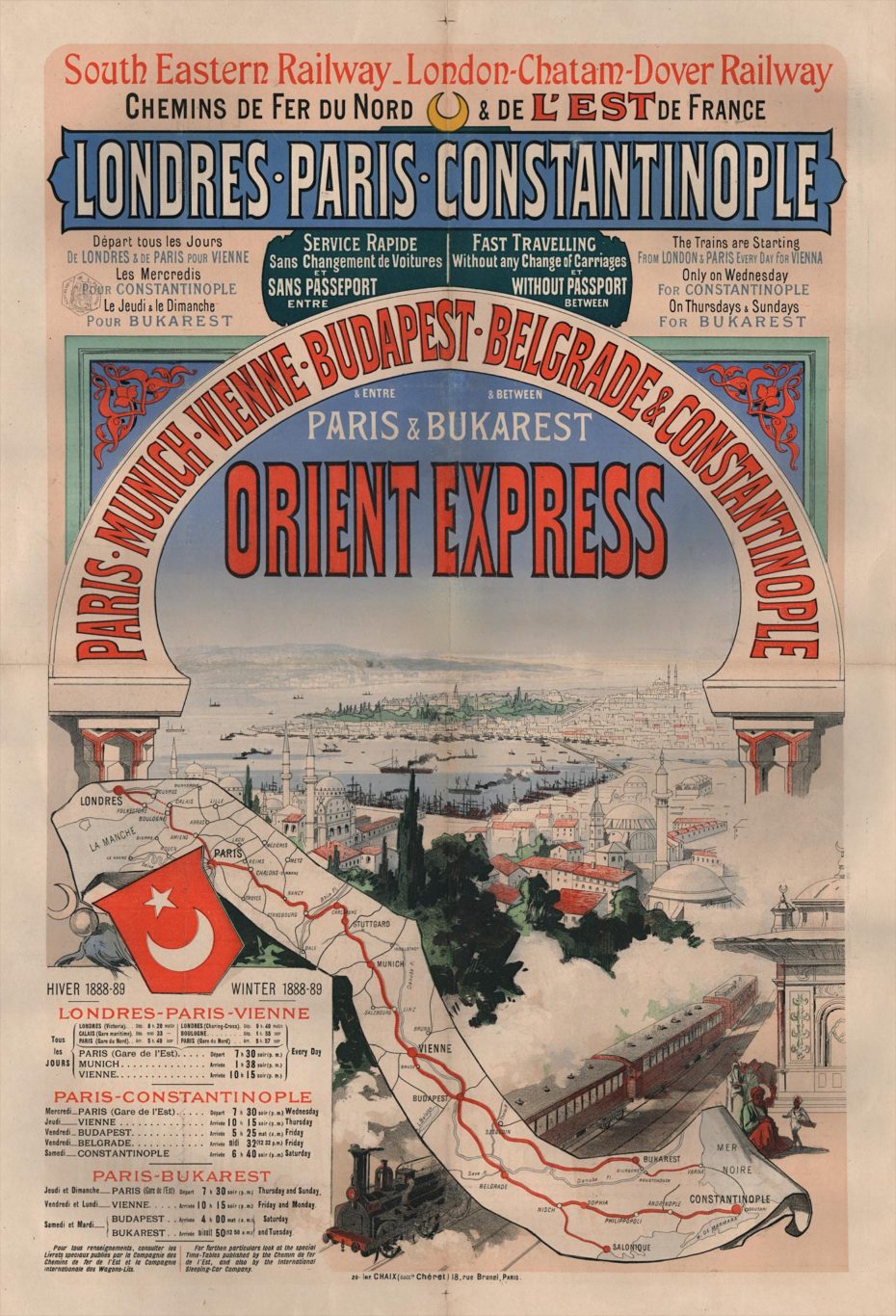

In June 1883, the first journey of the Orient Express departed Paris for Vienna before lengthening its route in October to Romania, where passengers would take a ferry across the Danube and continue the journey to Istanbul (then Constantinople) from Bulgaria on another train. Although this journey was a little disjointed, many consider this the first real voyage of the Orient Express. From 1889, the rails were fully connected across the continent, and the Orient Express ran seamlessly from Paris to Istanbul for the good part of a century. At its peak in 1931, the service operated 2,426 cars, including 1,320 sleeper cars, 714 dining cars, 210 lounge cars, and 182 van loads. But towards the end of the 20th century, as cheaper air travel replaced rail travel as the primary mode of transportation, the Orient Express service seemed to disappear without a whimper.

In 1977, the famous three-night journey on the Paris-Istanbul route was withdrawn from regular service, although it’s important to remember that the original was not an individual train, but a scheduled service that ran various routes across Europe. The Orient Express name has appeared under many guises over its almost 140-year history but today, France’s national state-owned railway company, SNCF, owns the rights to the Orient Express brand and has done for over 40 years. In a one-off licensing deal, American businessman James Sherwood launched the Venice-Simplon Orient Express train in the early 1980s using some of the original sleeping and dining cars. This luxury train, now owned by Belmond (an LVMH-owned company) makes a once-a-week service from London to Paris to Venice between March and November as well as a single novelty journey once a year to Istanbul. But over the last few decades, countless antique Orient Express train carriages were all but vanishing from the public railways of Europe without a trace.

Fast forward to 2015: the romance of train travel is having a comeback and the Accor hotel group is gearing up to buy a 50% stake in the Orient Express brand from SNCF to jointly revive the original service featuring the historic Paris–Istanbul route. There is just one problem – they don’t have enough original train cars. To track down the missing Orient Express carriages, SNCF turns to Arthur Mettetal, a young train enthusiast and researcher who is finishing his PhD on the history of the Orient Express. At a gathering of ferrivophiles in Paris, a group of railway enthusiasts who’d meet on Tuesday mornings on SNCF premises, he had heard whispers of the “Glatt train” – thirteen lost carriages of a once-revived 1970s Swiss venture called the Nostalgie-Istanbul-Orient-Express. After rummaging through archives and message boards, Mettetal finally spots something while scouring a very niche side of YouTube. He finds an anonymous video with little to no information, but the elusive midnight blue carriages he’d been looking for can be seen in the background. There isn’t much to go on except for a detail he can zoom in on when he presses pause – the station’s name: “Małaszewicze”.

The search isn’t over, as there are some ten “Małaszewiczes” stations in Poland, which means Arthur Mettetal has to pore over Google Maps and zoom in for each piece of Polish rail clues searching for the carriages. He gets lucky eventually, finding evidence of what looks like 13 abandoned train cars in a town near the Polish-Belarussian border. Upon zooming in, he can make out the grey-white rooftops typical of the Orient Express, and in Street View mode, he catches a glimpse of the iconic blue he’s looking for.

He makes it out to Poland to see them for himself, along with a translator, a photographer, and an SNCF manager in tow. It’s an adventure in its own right, involving a four-hour ride from Warsaw to the Belarus border, where they stay in a run-down motel allegedly belonging to a local crime organisation. And in one particularly hairy moment, the small group even finds themselves being threatened at gunpoint as they arrive at the depot where Arthur suspects the carriages are being kept. Thanks to the intervention of the translator who explains their mission to the unfriendly security, finally, they get to see the missing carriages – which to Arthur Mettetal’s delight are in fantastic condition, with original Lalique glass panels engraved with blackbirds and grapes still intact.

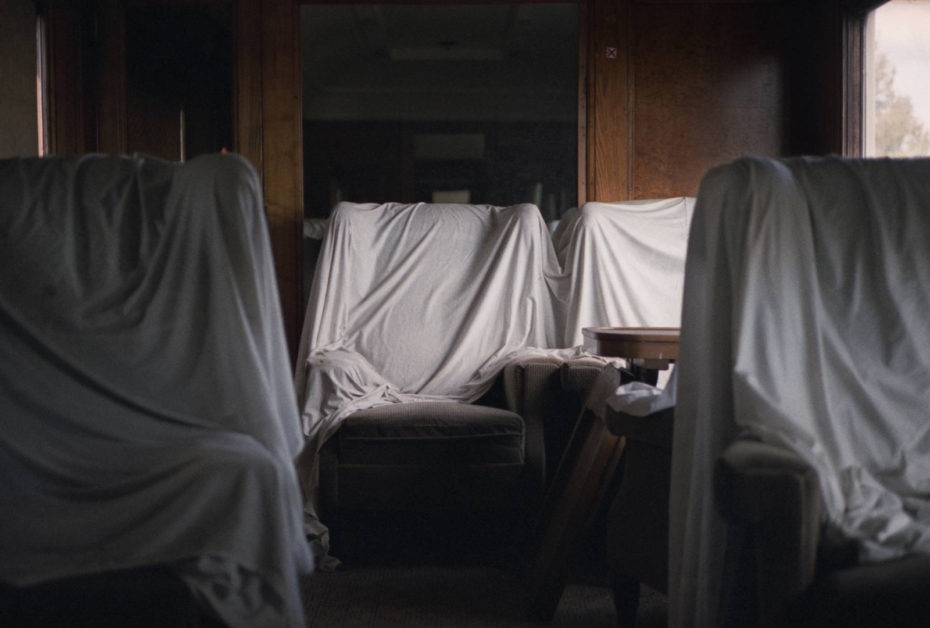

After much negotiation, in 2018, the carriages were escorted from Poland by a police convoy and eventually returned to France where they could begin the long process of restoration to their former glory. Elsewhere in France, a private collector was found to have accumulated a large number of Orient Express cars over several decades, but their state of decay was so advanced, they could not be salvaged. Four more carriages however, were found in better condition in Switzerland and Germany, bringing the total up to 17 cars, including 12 luxurious sleeping cars, a dining car, three lounges and a van. With enough trains recovered, it was time to bring them back to life.

Even today, the industrial scale of the Orient Express can still be seen along its route, including some of its old workshops; former office buildings and agencies, and rolling stocks. Although on first impression, these may not seem like a sexy part of the Orient Express’s history, Arthur Mettetal found that delving into this part of its history helped him understand the complete story. By visiting them and delving into their archival information – he found vital information for the 21st century rebirth of the luxury train line.

The network of warehouses and workshops across Europe served to provide all the necessities needed for the epic voyage, not only supplying technical parts for the train, but guest amenities from fine wines to soap. In addition to a wide range of staff of cooks, waiters and conductors on board, there were trackside warehouses along the routes tasked with everything from technical maintenance to laundry and storage of provisions (including thousands of bottles of wine). The Orient Express would not have been what it was without these workshops and warehouses tending to the passing trains. And thanks to this latest revival, new jobs will be brought back to these hidden but vital hubs of activity behind-the-scenes.

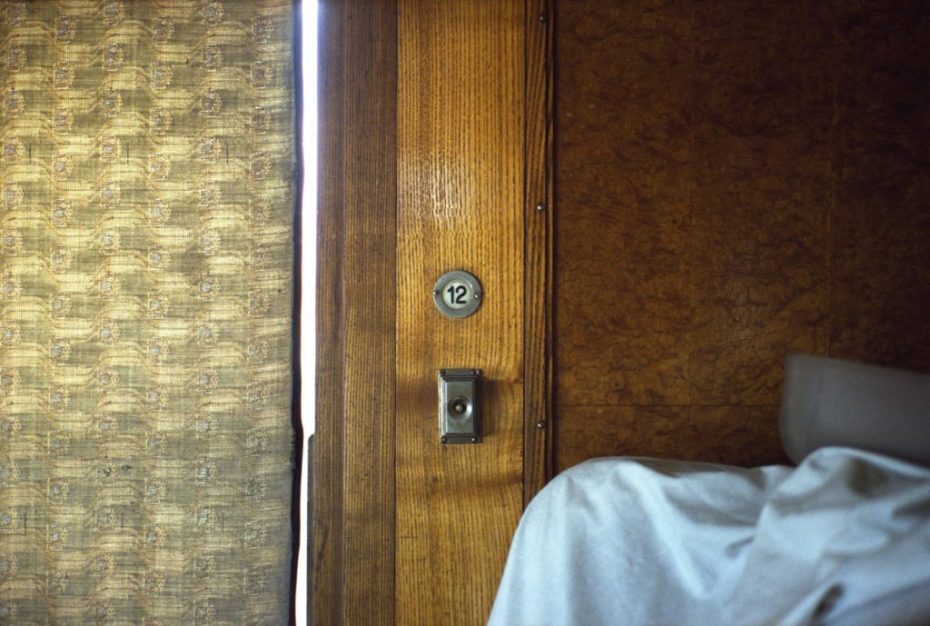

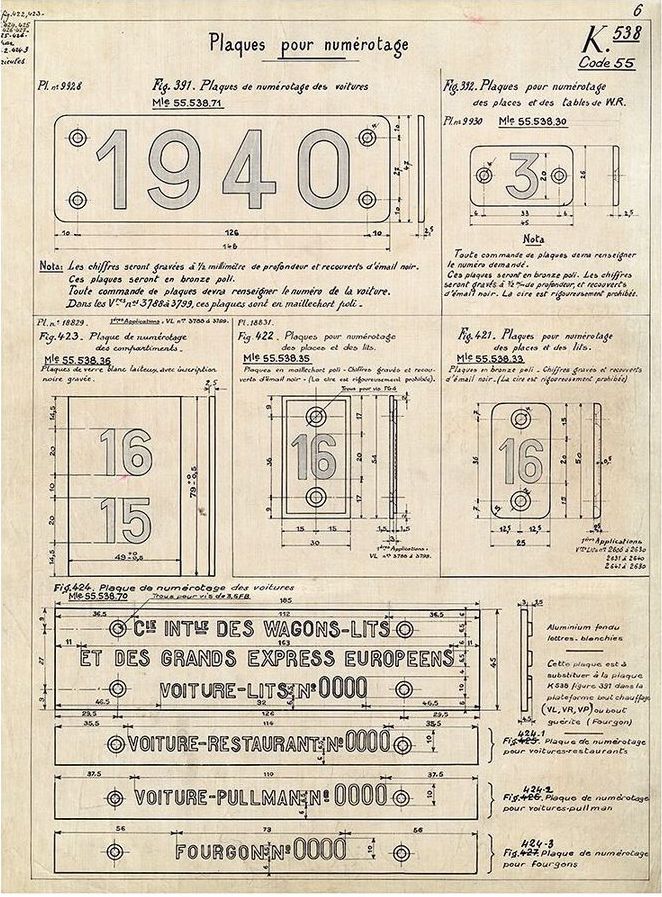

It’s the little details that also clue us into the scale of this ambitious operation. These details have been preserved in the archives, making it easier for modern-day restorers to recreate the cars as specified. Equipment came from Austria, France, Belgium, Italy, and England, but in order to maintain the standard expected from the Orient Express, engineers were supplied with very unique and precise specifications in the form of detailed technical drawings that left nothing, not even a single screw, out of the instructions.

The Orient Express might be a feat of technological innovation, extensive people-power, and meticulous planning, but much of its legacy lies wrapped in the filigrees of its details. The beauty of the Orient Express was its marriage between industry and craftsmanship, blending the metallic exterior of the cars with the plush interiors of their carriages. From the art of marquetry by Morrison and Nelson to the engraved glass panels of René Lalique, where even the nuts and bolts bear the signature of the Orient Express, no detail was left to chance. Renovating the Orient Express to capture the train at its peak means staying true to this level of detail.

Fortunately, the recovered carriages were well intact, except for the wear and tear of time. With Arthur Mettetal’s vast collection of archival documents, old photographs, and more, the missing details can be put back together in the hands of skilled crafts professionals. Smelters, upholsterers, woodcarvers, glass makers, and furniture makers have all been working to put the train back together.

In their workshops, the ancient René Prou armchairs, iconic of Pullman Salon-Cars, are fully restored by masterful woodworkers, sculptors and upholsters © Orient Express Heritage / Lola Hakimian

Parisian architect and designer Maxime d’Angeac is leading the restoration of the service and has sourced the best materials, from velvets and silks to crystals and bevelled mirrors, as well as wood like mahogany and elm burr to maintain the old-world opulence. Poring over the old sketches, drawings, and models made by hand, d’Angeac reinterpreted the history of the train to make its operation a reality again. In a world saturated with plastic and robot-operated production, it’s reassuring to see the level of artisanship and handcrafts being used.

The Orient Express by the Accor Group is set to hit the rails again in 2025, in large part thanks to Arthur Mettetal who recovered the missing carriages with his historical sleuthing and chronicling. You can see some of his research on his Instagram account, Orient Express Heritage, where he shares his findings of all the big and little things that made the Orient Express legendary. He now holds the coveted role of Director of Culture, Art & Heritage at the Orient Express brand. Talk about a dream job.