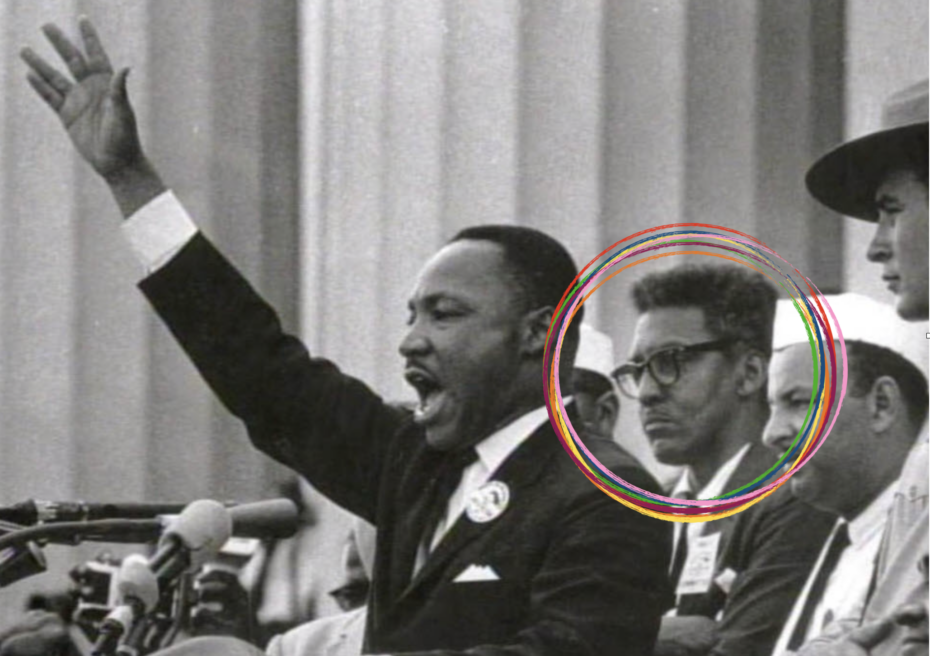

The list of people who attended the March on Washington — Martin Luther King Jr., Josephine Baker, John Lewis and Harry Belafonte — it’s a who’s who of the activists, politicians and celebrities who defined the Civil Rights Movement. But Bayard Rustin, a trusted advisor and mentor of Martin Luther King Jr., who organised the event where Rev. Dr. King made his famous “I Have A Dream” speech, has been mostly left out of the history books – largely because he was an openly gay Black man. Without the behind-the-scenes work of Rustin, Martin Luther King’s iconic moment wouldn’t have been possible. For generations, Black LGBTQ+ people have been on the frontlines of the fight for Civil Rights, but in so many cases their contributions were scrubbed from the historical record. Pride Month, and the upcoming 50th anniversary of the march this summer, are opportunities to dive deeper into one of the most influential activists, who not only advocated for Black liberation but for many minority groups facing discrimination, notably for gay rights and Soviet Jews.

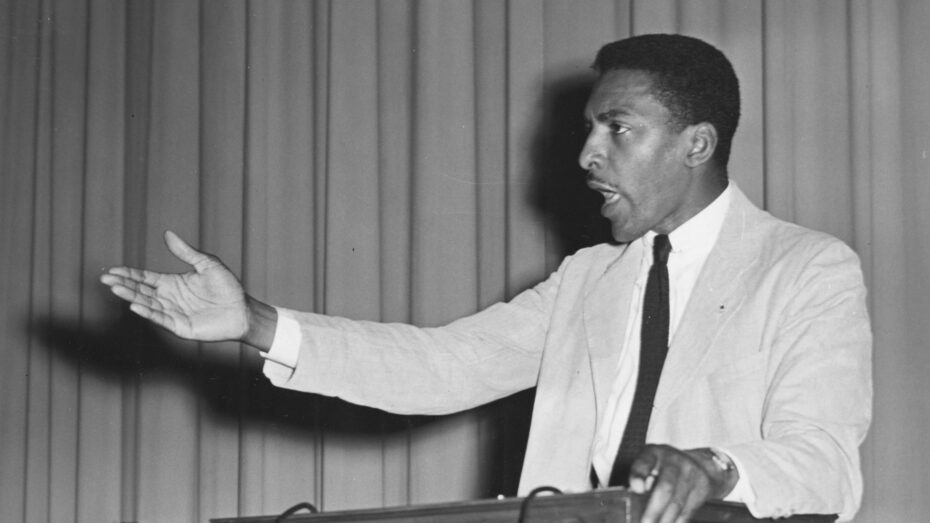

“We need, in every community, a group of angelic troublemakers”

Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin was born in Pennsylvania, the ninth of 12 children. He was raised by his grandparents and his grandmother Julia was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Civil rights leaders such as W.E.B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson regularly visited their home and Rustin became involved in the fight against the discriminatory Jim Crow laws from a young age.

He studied at Wilberforce College, a historically Black college, but was kicked out for organising a strike (against bad cafeteria food) and then enrolled at Cheyney State Teachers College. He took an activist training course organised by Quakers, a movement his grandmother was also attached to. He eventually ended up at City College in New York, where he took part in his first major civil rights action: trying to free the Scottsboro Boys, nine young Black men from Alabama who were famously unjustly accused of raping two White women.

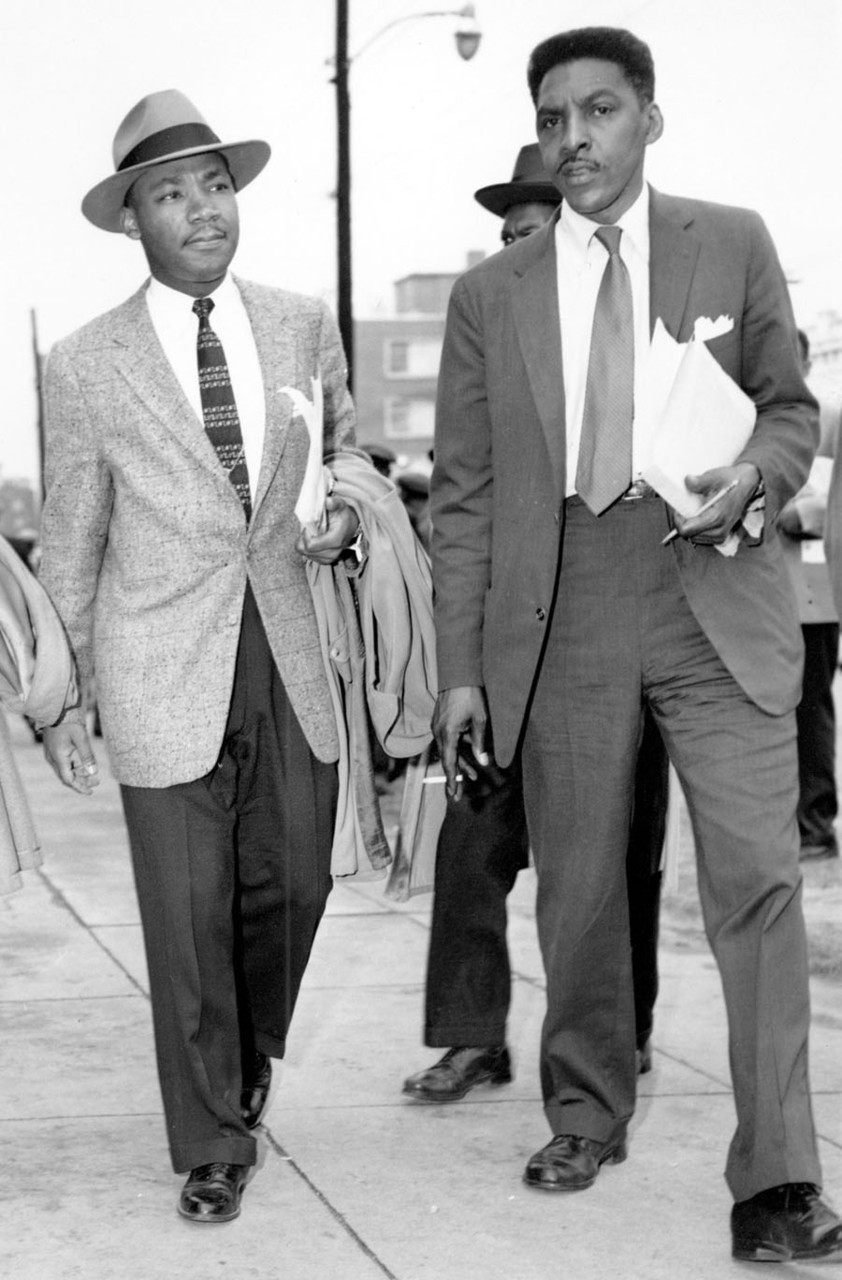

The Second World War further revealed to Rustin the inequalities facing not only African Americans but other minorities. He went to the Oval Office with another important Civil Rights figure, A. Philip Randolph, to tell President Roosevelt that he and other activists would organise a march in Washington if he failed to desegregate the armed forces. (They called off the protest when Roosevelt signed the Fair Employment Act.) Rustin also helped preserve Japanese Americans’ property while they were imprisoned in internment camps.

Rustin himself experienced the brutal impacts of racism when he was taking a bus from Louisville in 1942 and sat in the second row. He was beaten up by police. Like King, Rustin was deeply influenced by pacifism, including the beliefs of Mohandas Gandhi. By the late 1940s, he was organising the first Freedom Rides (known as the Journey of Reconciliation) with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Over the next few years, he served on a chain gang for his activism and traveled to India to learn the tenants of non-violent resistance, which he brought back to the United States when he became an advisor to King.

Rustin was successful in shaping the 1955-1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott, which would prove to be a turning point in the Civil Rights Movement. While he also helped develop the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the organisation that King headed, others in its leadership forced Rustin out because of his sexual identity. At this point, Rustin was dealing with vitriol from both sides: South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond described him as a “Communist, draft-dodger and homosexual” and even accused him of having an affair with King.

The setbacks didn’t stop Rustin from forging ahead on the movement’s next major action: the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Some 200,000-300,000 people from across the country attended the march, which featured the “Big Six” heads of the NAACP, the SCLC, the National Urban League, the Conference of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), led by future political leader John Lewis.

Rustin worked closely with Randolph, who he had previously gone to the White House with, to plan the mile-long march from the National Mall to the Lincoln Memorial. The three hours of programming at the Memorial featured speeches, musical performances and sermons from religious leaders. In just a few months, Rustin worked with 200 volunteers to organise what would be the largest peaceful demonstration in American history. But NAACP chairman Roy Wilkins wanted to centre Randolph’s role in the march while keeping Rustin out of the spotlight, given his “liabilities.”

In an essay Bayard wrote in the late 80s, he shared his thoughts on how Dr King felt about gay people.

“It is difficult for me to know what Dr. King felt about gayness except to say that I’m sure he would have been sympathetic and would not have had the prejudicial view … Otherwise he would not have hired me. He never felt it necessary to discuss that with me … I think at a given point he had to reach a decision. My being gay was not a problem for Dr. King but a problem for the movement.”

Rustin’s supposed controversies did not interfere with the impact the march had, with organisers meeting with President John F. Kennedy afterward. The event brought the Civil Rights Movement to a global audience, with the program translated into some 36 languages, and played a significant role in pushing the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

And Rustin did not let up in his fight for racial equality, organising some 400,000 New Yorkers who were boycotting segregation in New York City public schools in February 1964. Rustin also sought to build closer relations between the Civil Rights movement and the Democratic Party, partially following the Civil Rights Act. He outlined this shift in an article entitled “From Protest to Politics,” published in the magazine Commentary. He highlighted in particular the importance of focusing on ”the American socio-economic order and to the fundamental conditions of life of the Negro people.” In other words, what is the point of de-segregating a restaurant if Black people couldn’t afford to eat there?

“All these interrelated problems, by their very nature, are not soluble by private, voluntary efforts but require government action—or politics,” he wrote. “Already Southern demonstrators had recognized that the most effective way to strike at the police brutality they suffered from was by getting rid of the local sheriff—and that meant political action…”

Along these lines, Rustin also became increasingly involved with labor action with the country’s leading unions and served in the leadership of his the Socialist Party of America. Although, he was also criticised for a conservative turn by the end of the 1960s, having expressed criticism of the role of identity politics within the Civil Rights Movement and anti-communist sentiments during the War in Vietnam and the Cold War. In reality, he had a particular interest in aiding Soviet Jews, who faced significant discrimination in the USSR. He pushed at both the national level and within the United Nations for them to be able to practice their religion freely and have opportunities to immigrate. (His work played a role in some half a million Jews being able to leave the Soviet Union and come to the United States as of 2005).

Bayard’s last civil rights fight would take a personal turn. He had never completely hidden his sexuality. Davis Platt, his partner in the 1940s, told Magazine of History that Bayard didn’t feel “any shame or guilt about his homosexuality.” Bayard’s grandmother had supposedly also told him “I suppose that’s what you need to do,” concerning his preference for spending time with men. But it was his later-in-life partner, photographer Walter Naegle, who encouraged him to get involved in queer activism as HIV/AIDS was decimating the gay community.

While Bayard said he considered sexual identity to be a “private matter,” he testified in support of New York State’s 1986 Gay Rights Bill, which aimed to ban discrimination based on sexual orientation in the fields of employment, housing and public accommodations. In a speech from that year entitled “The New N*ggers Are Gay,” he said, “The question of social change should be framed with the most vulnerable group in mind: gay people.”

Bayard died in 1987 of a perforated appendix. Naegle, who Bayard had adopted in order give their relationship a level of legitimacy and protection, has continued to carry on his partner’s legacy, including serving as the executive director of the Bayard Rustin Fund. In 2013, President Barack Obama posthumously gave Rustin the Medal of Freedom for his work on the March on Washington.

As Naegle said when he accepted the award on Bayard’s behalf, “Being Black, being homosexual, being a political radical, that’s a combination that’s pretty volatile and it comes along like Halley’s Comet. Bayard’s life was complex, but at the same time, I think it makes it a lot more interesting.”