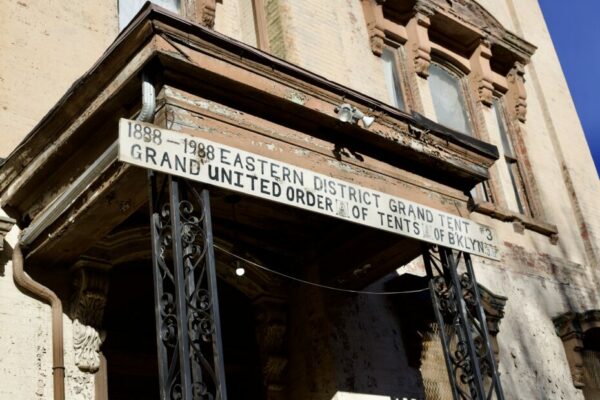

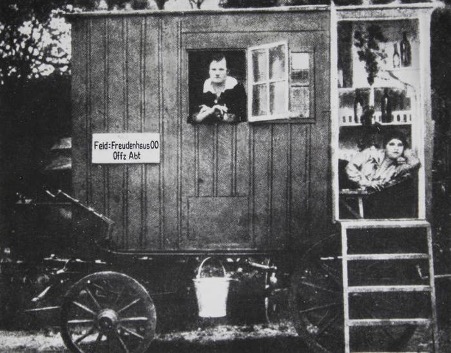

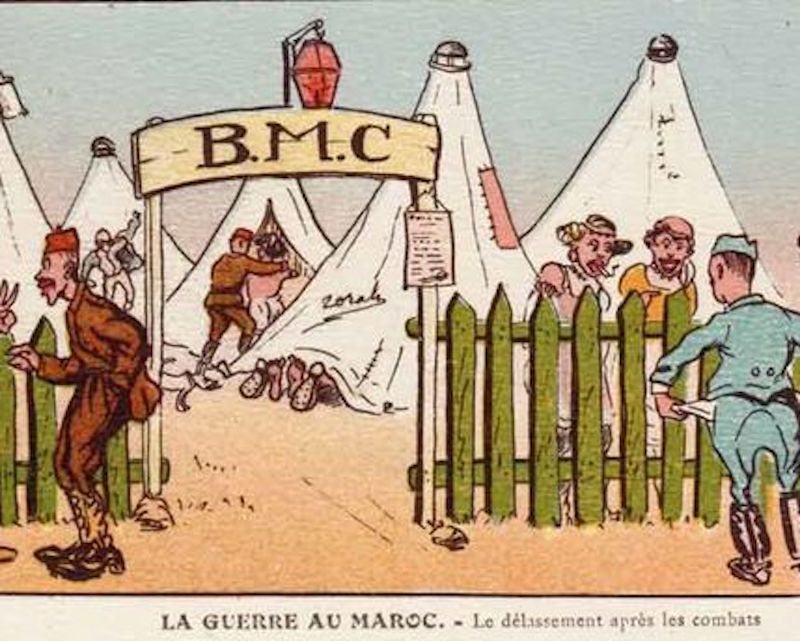

Sex and war are seemingly the uneasiest of bedfellows, nonetheless, they’ve have had a most intense relationship over centuries of conflict. As early as the Third Crusade, Philip II of France, horrified with the rampant rape and sodomy in his armies, instructed boatloads of “girls of joy” to be dispatched from France to “re-focus” his troops. Seven hundred years later, the French state was still supplying mobile battleground brothels, known as Bordels Mobiles de Campagne (or BMCs), present during both World Wars, the occupation of Algeria as well as other French Colonial territories, and controversially, were at military bases as recently as 2003. “Sanctioned” sex workers, although never publicly acknowledged by authorities, have been a longstanding part of our armies since at least Alexander the Great’s Roman campaigns. These just aren’t the kind of war stories that ever made it home.

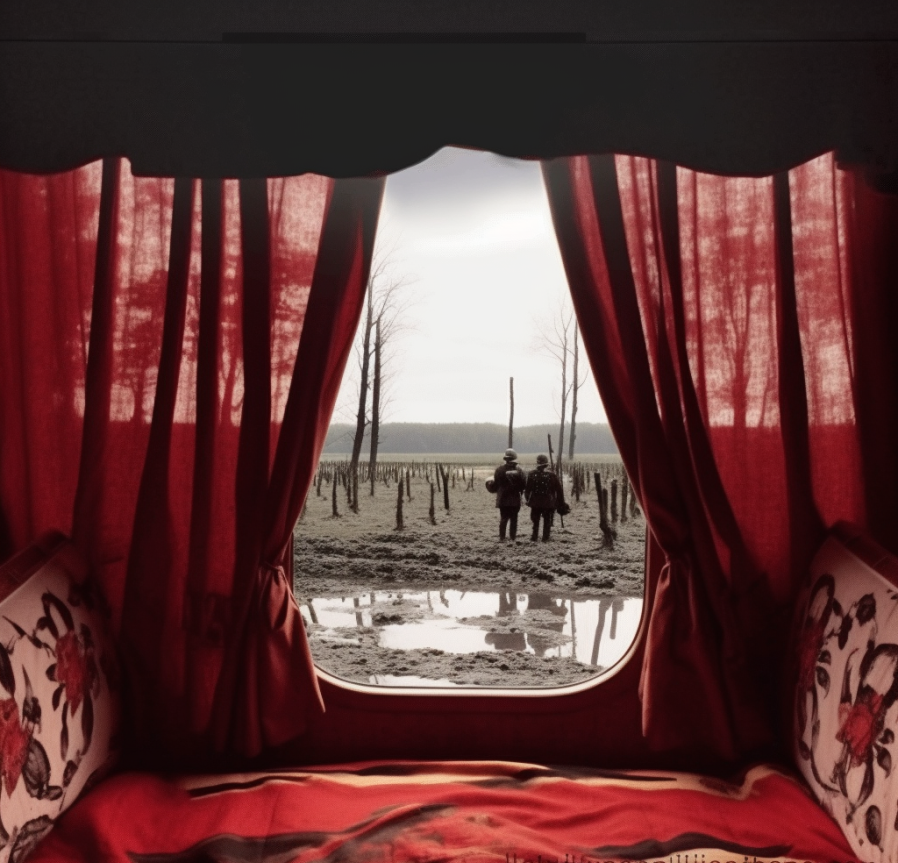

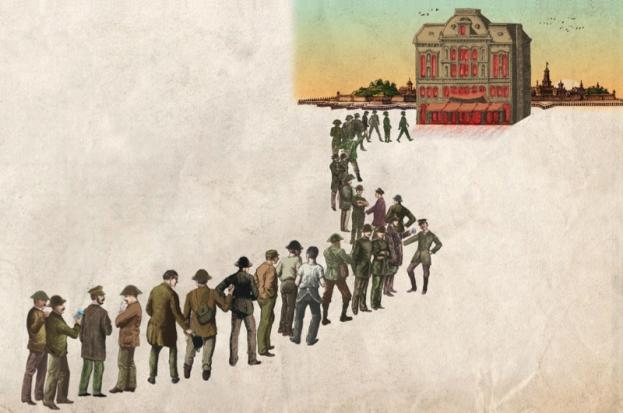

During World War I, the French government actively provided prostitutes for its troops on a grand scale. While not officially mentioned in military documents until at least the 1920s, records show that a government-run association dedicated to co-ordinating mobile military brothels existed as early as 1901, with an official address at 73 rue de Nazareth in Paris. During World War I, these mobile facilities, literally large trailer trucks known as BMCs, could accommodate up to 10 working women on the frontlines of war. The mass of young men being sent to the frontlines drove demand, and more prostitutes and pimps followed. Not only did the authorities provide its own sanctioned army of professional sex workers, but local girls around the camps and battlefields also resorted to prostitution in these times of desperation. Demand usually peaked before the major battles.

French Doctor and author, Léon Bizard wrote in his memoirs of the WWI French mâison tolérés;

You could find anything you wanted in the brothels in the surrounding area and at the camps. It was a mêlée, a hard, dangerous and disgusting business … all under the constant threat of air raids and bombardments.

Aside from being key to maintaining control over large amounts of battle-worthy men, there were other motivations for providing troops with sanctioned prostitutes. With the arrival of indigenous units from the colonies on the French mainland, the deployment of sanctioned brothels were partly driven by racist and classist motives to prevent interracial relationships from occurring with local French white women.

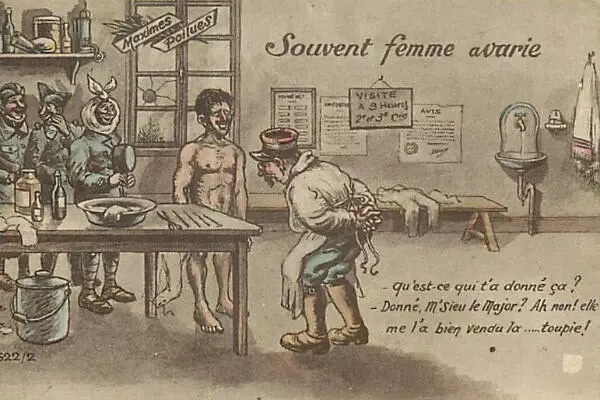

But perhaps one of the most urgent motivations for the military overseeing the sexual activity of its soldiers was to control STD rates. Whilst the crashing hail of bullets and shells killed on the battlefields of war, syphilis was the silent killer. With an estimated syphilis rate of 30% among the military during WWI, something had to be done. Attempts to trace infections by pressurising both men and women failed, and as early as 1915, the French military doctors had set up treatment centres for soldiers, while the regulated brothels were subject to regular medical inspections.

It also became apparent that some men deliberately intended to visit girls who could infect them with STIs. A hospital stay to treat Syphilis or Gonorrhea meant a thirty day treatment off the battlefield. The rate of infection of the British and Empire soldiers, who were ‘allowed’ to visit brothels if they were overseas was estimated at 1 in 5 by 1916. And like all things of class-based society, the officers went to the Blue Lamps facilities, the ranks to the Red.

In 1963, Belgian crooner Jacques Brel wrote a song about the BMCs from the perspective of a soldier. Later, an English cover was written and featured in a 1968 musical called “Jacques Brel is Alive and Well and Living in Paris.” Take a listen below…

But what of the women providing these state-sanctioned services? British poet and author Hollie McNish felt drawn to write about the sex workers forgotten by hour wartime history books, whose role “in every single war – is so often belittled and shamed and overlooked – it isn’t really seen as a role at all. The [syphilis] posters of these demon-portrayed women says it all really.”

The subject of an art project she called Cause and Effect, McNish poignantly capturs the brutal suffering of these women serving soldiers and their country …

During World War II, the Japanese enslaved and trafficked as many as 410,000 women they called “comfort women” from Japan, Korea, China, and Southeast Asia to serve as prostitutes and raise the spirits of the Japanese soldiers. It’s thought that approximately three quarters of them died and most survivors were left infertile.

Traffickers and profiteers were tricking girls with fake promises for jobs, and in some cases, government and traffickers worked together to put women originally drafted for forced labor into prostitution. In the newly conquered colonies like Vietnam or Indonesia, comfort women were more directly obtained by collaboration between the army and traffickers who followed the army.

It was an open secret that the U.S. military made use of the “Comfort Women” system in Japan following the end of the war. As the US forces and Australians (who originally occupied Hiroshima and surroundings before handing over to the Americans) entered Japan, provisional leaders feared that local women might be subjected to “mass rape”. Prince Konoe Fumimaro, who served as Japan’s Prime Minister insisted that “comfort stations” be made available to arriving troops of the post-war occupation.

Adverts appeared in Japanese newspapers seeking prostitutes to provide sexual services to the arriving U.S. troops, who would come to know these women as “geisha girls“ which further fuelled the misunderstanding of geishas as prostitutes in the West.

Meanwhile, in 1950s Vietnam, the French had a base at Dien Bien Phu, where seven Vietnamese women and 11 Algerian women were deployed in BMCs to serve 16,000 soldiers. But as the situation got worse for the doomed French outpost, the women became the unlikely heroes, working as nurses. In his book Hell in a Very Small Place, written by journalist Bernard Fall, who was embedded with the garrison, their forgotten story is shared in harrowing detail.

The five Vietnamese girls and their madame had been caught in the battle like everyone else and had lived through it in underground bunkers as auxiliary nurses, like the Algerian prostitutes who had also been unable to leave and had stayed on …

Often the women were seen in the water of a trench up to their hips, waiting to help the wounded in a strongpoint. In one case, a shell-shocked soldier had developed a fixation that he was a small child and had to be fed by his mother; one of the Vietnamese prostitutes came to this dugout every day to feed him.

Of the 11 Algerian prostitutes, four were killed during the battle. It’s not known what happened to the Vietnamese women. Some reports say they were executed for collaboration.

Unlike the American military who denied the problem or the British who turned a blind eye, the French discreetly continued the practice until it became politically unacceptable in a modern, liberal world.

France continued to employ Bordels Mobiles de Campagne well after WWII, although by 1946, brothels had been outlawed in France. The last BMC on French territory in French Guiana closed in 1995, allegedly following a complaint by a Brazilian pimp for unfair competition. And it wasn’t until 2003 that they closed another in Djibouti.

When war is over, we prefer to look ahead and not dwell on the grim details of the past, so we talk romantically of heroes of the battlefield, the industry and workforce that empowered their fight; but not of exploitation, prostitution and sexually transmitted diseases. Not to the public taste, the intermingling of sex and wartime has been left out of the history books, but like war, it will not go away.