If you were to take a walk in Mumbai’s Hanging Gardens on Malabar Hill, one of the city’s most exclusive neighbourhoods, you might notice vultures circling above the trees in the distance. Behind the park’s manicured lawns and elegant flower gardens lies a 54-acre forest, home to five circular structures known as the Towers of Silence where people of the Zoroastrian faith leave their dead to be scavenged by birds in a matter of hours. Stick with us…

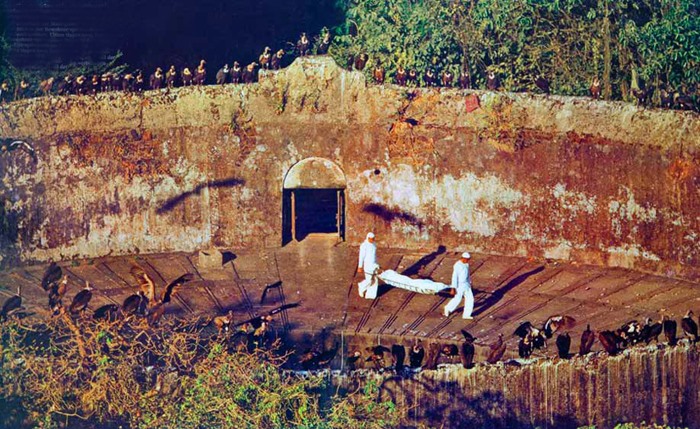

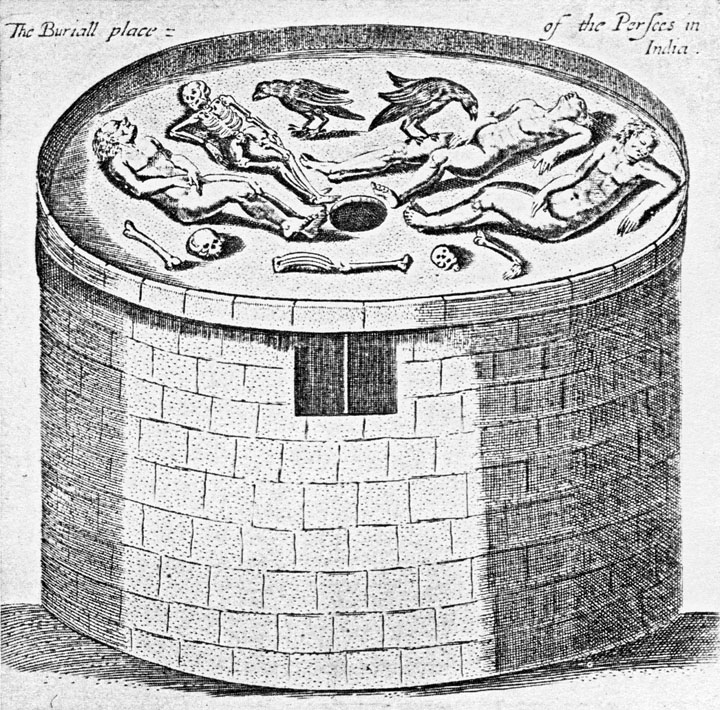

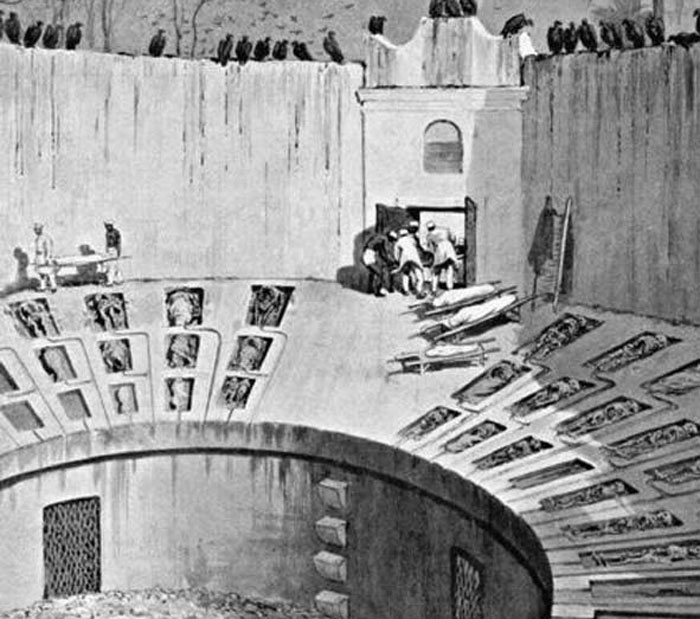

Locals spin many haunting stories about these mysterious structures, but there is a somewhat “practical” explanation. The stone towers serve the funerary rites of the Parsi community, an ethnoreligious group from Persia who are followers of the ancient Zoroastrian faith, based on the teachings of the prophet Zoroaster and worship of the winged god Ahura Mazda. According to the Zoroastrians, burying bodies is thought to taint the soil. As the story goes, when the body dies, Nasu, the corpse demon, is believed to rush into the body and contaminate everything that comes into contact with it. So in order to keep not just the earth clean, but also water, fire and air unpolluted (all considered sacred in the Zoroastrian religion), the Zoroastrians had to devise a rather unorthodox way to dispose of corpses, which is where the towers come in. These sky burials, folklore aside, are actually a pretty eco-friendly tradition that dates back thousands of years.

But Mumbai is India’s most densely populated city, and you’ll find the Towers of Silence in one of the city’s most affluent neighbourhoods, so what’s the story here?

The Parsi people came to India around the 10th century AD, escaping the Arab conquest of Iran but in 1672, the English Governor of Bombay (Mumbai today) allocated the Parsi community some land on Malabar Hills to use as their burial ground. But as the city grew and expanded over the centuries, it developed around the forest.

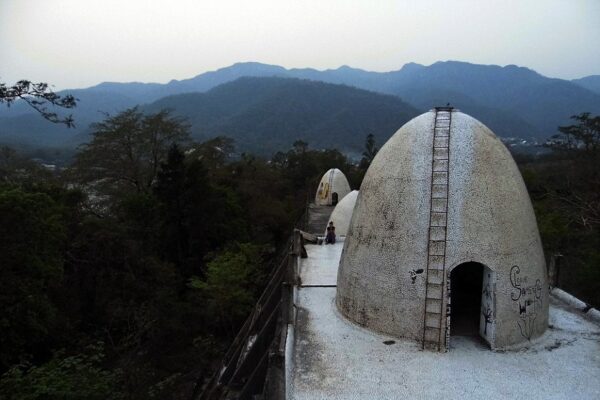

These towers, known as Dakhma, are no longer in use in Iran (the practice became outlawed there in the 1970s) and can be visited as archaeological monuments, unlike the ones in Mumbai.

Until recently, they were just a part of Mumbai life, but in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the vulture population in India declined by 97% when the introduction of anti-inflammatory medication in livestock in the 1990s started poisoning the birds with a syndrome known as “drooping neck”. Although the medication was banned in 2006, the disappearance of the vultures impacted the sky burials almost immediately.

The decrease in the vulture population meant that the Zoroastrian tradition started to do the very thing it was designed not to do: pollute. Those living on Malabar Hill frequently complain of the smell wafting from the Dakhma. Although the towers are strictly off limits to non-Parsis, and the Dakhma are only open to the special caretakers known as khandias or nasa salar (meaning caretakers of pollutants), in 2006, someone snuck in and took videos and photographs of decaying bodies, which when published sent shockwaves across Mumbai and its Parsi community. Many in the Parsi community, including eminent doctors, also warned that the towers posed a significant health hazard and epidemic risk without vultures to consume the dead. So, the community needed to find a solution.

There was an initiative in 2010 to breed vultures in captivity and build aviaries around the towers on Malabar Hill but this was unsuccessful. Other methods were also tried, including powerful solar concentrators to help desiccate the corpses using sunlight, but this method is controversial among the Parsi community and was also found ineffective during the monsoon season. Many Parsis in Mumbai now opt for cremation today, but orthodox Zoroastrians and many Parsi priests consider this to be an abomination as fire is considered sacred and not to be contaminated by corpses.

You can find these sacred but curiously morbid monuments all over India, however, it remains to be seen whether the tradition will continue. Radiolab released a fascinating episode all about the Indian vulture crisis and its impact on Zoroastrian burial practices.