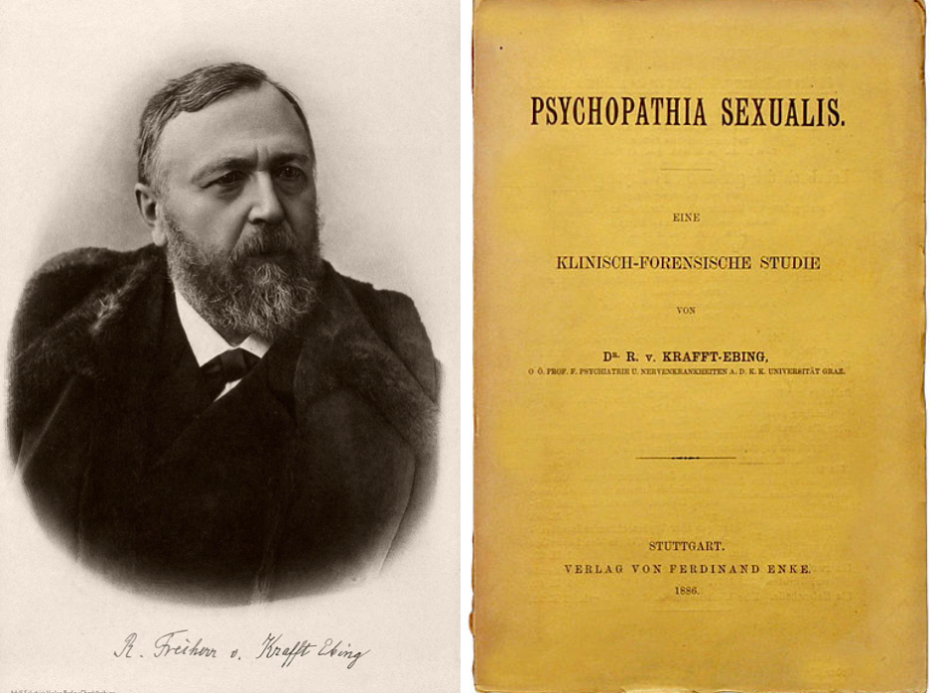

Forget Freud. Today, we’re snooping around the personal archives of Richard von Krafft-Ebing, a 19th century psychoanalyst and sexologist extraordinaire who history has often been forgotten despite his groundbreaking research in sexual pathology. His chef d’oeuvre is undoubtedly Psychopathia Sexualis, the book that made jaws drop across Europe in 1886 and the first-ever scientific study on sexual deviation. “For almost one hundred years,” explains psychologist and sex researcher Dr. Joseph LoPiccolo, it “stood as the world’s most informative volume on the subject of sexual deviation.”

Krafft-Ebing’s research preceded Freud’s by decades, and Sexualis included over 238 case studies exploring “sexually deviant activities” like sadism, masochism, fetishism and more. Plus, he coined the term “anilingus”.

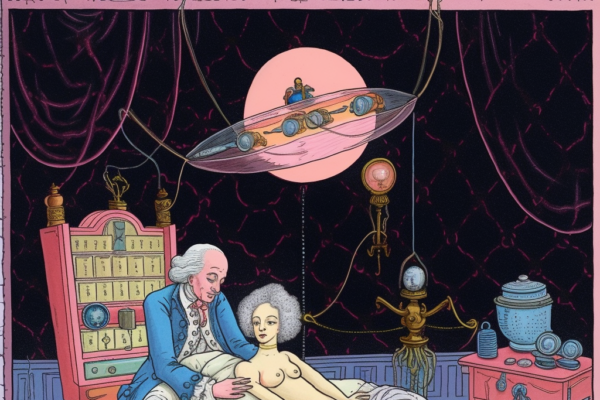

A book to make you blush, no doubt — but Krafft-Ebing took his kinky content very seriously, explaining that it was intended for “study in the domains of natural philosophy and medical jurisprudence.” On the surface, he appeared every bit the prim and proper academic, living a quiet, conventional life with his wife Marie-Louise…

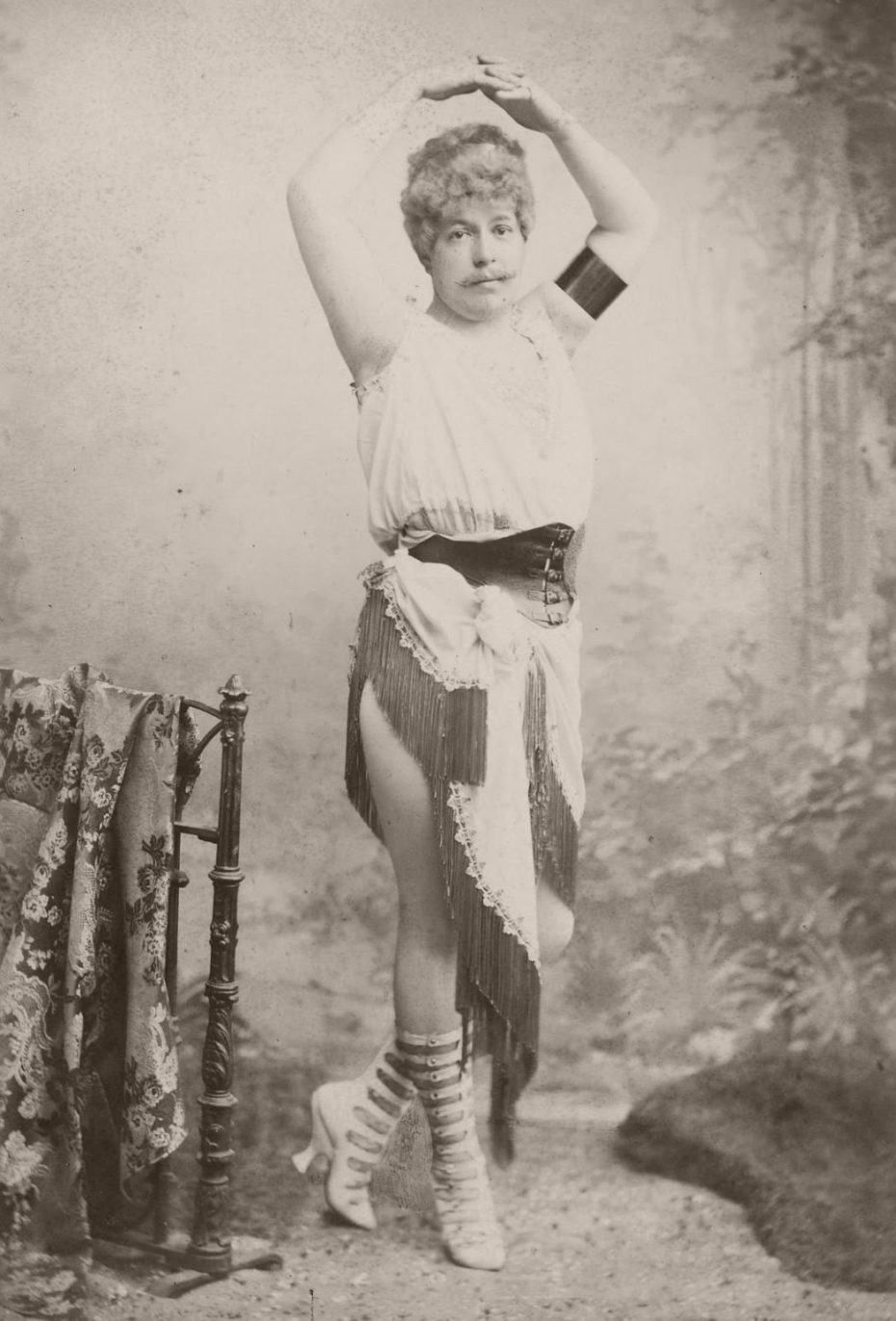

Then, after his death in 1902, a series of raunchy post-cards and photos were found randomly among the papers in his personal library. The archives themselves only went on display a few years ago for an exhibit at the Wellcome Collection museum in London, and they’re actually the only archives we have from the eccentric sexologist (whose seminars were described as “showy,” “glamorous” and “highly sensational”). “The photographs must have been taken in the second half of the nineteenth century, but they were never published or discussed in writing. Visitors immediately noted the elaborate studio setting and the careful selection of props and costumes,” noted Dr Jana Funke. There’s also some spanking, blindfolding, and quite a bit of cross-dressing in the small collection…

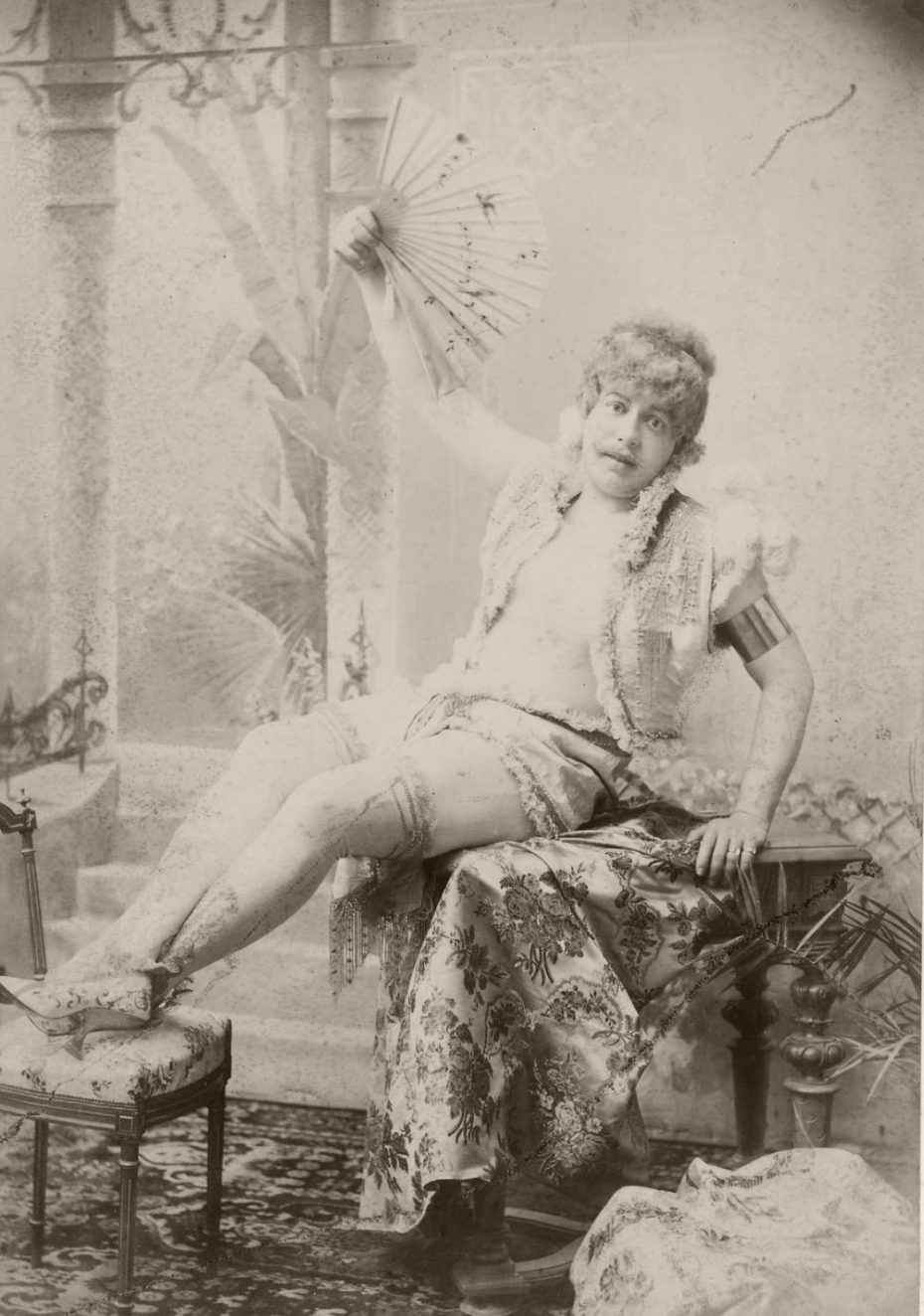

But the star of the lot is indisputably a man who has come to be known only as “the anonymous cross-dresser”:

“Looking at the images,” explains sexologist Dr. Jana Funke, “we noticed how the photographs had been manipulated: if you look closely, you can see what can best be described as nineteenth-century ‘photo-shopping’. In several of the images, the contours of the hips, bottom and feet are redefined, so as to make the body appear more ‘feminine’.”

Then there’s the question of how on earth he got his hands on the pictures. “Cross-dressing was heavily regulated and even criminalised in many European countries at the time,” says Funke, “We wonder how private these images really were. Perhaps they circulated among a small group of people.” Above all, it makes one wonder if herr doktor was into dressing up himself.

Whether he had them for research or personal pleasure, Krafft-Ebing’s images provide a rare glimpse into often ostracised chapters of history. And although many of his theories have fallen to the wayside today for their archaic nature (i.e. his stance on homosexuality as an illness), he still got the sexology ball rolling with impressive momentum.