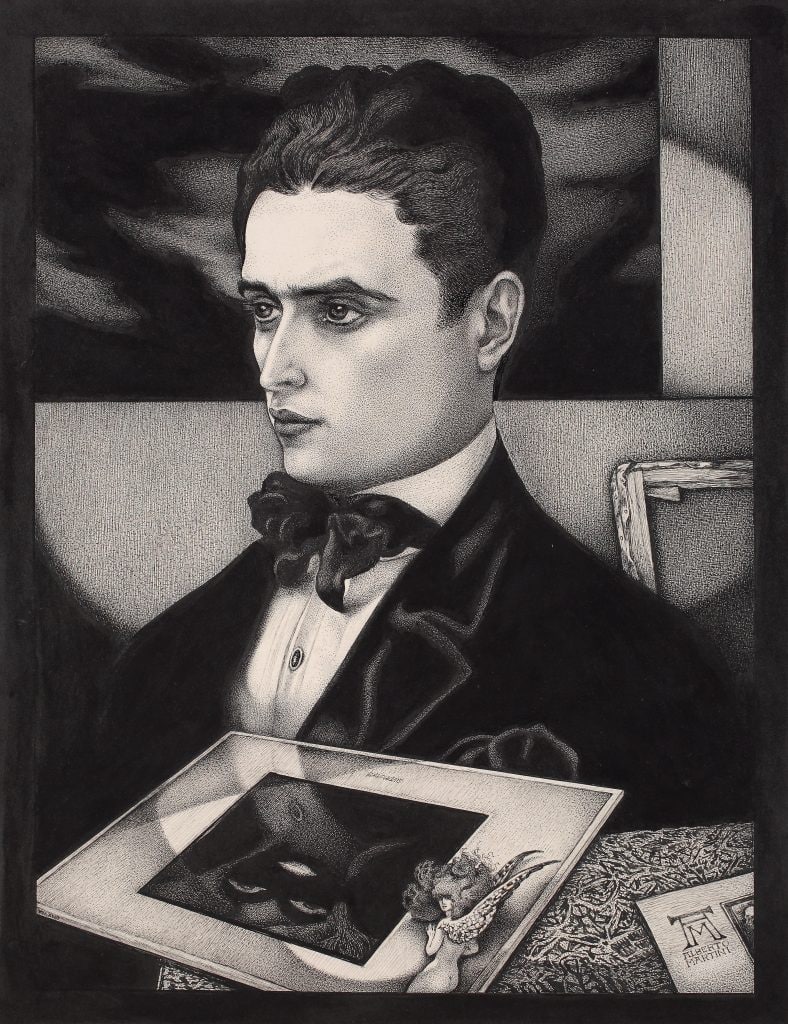

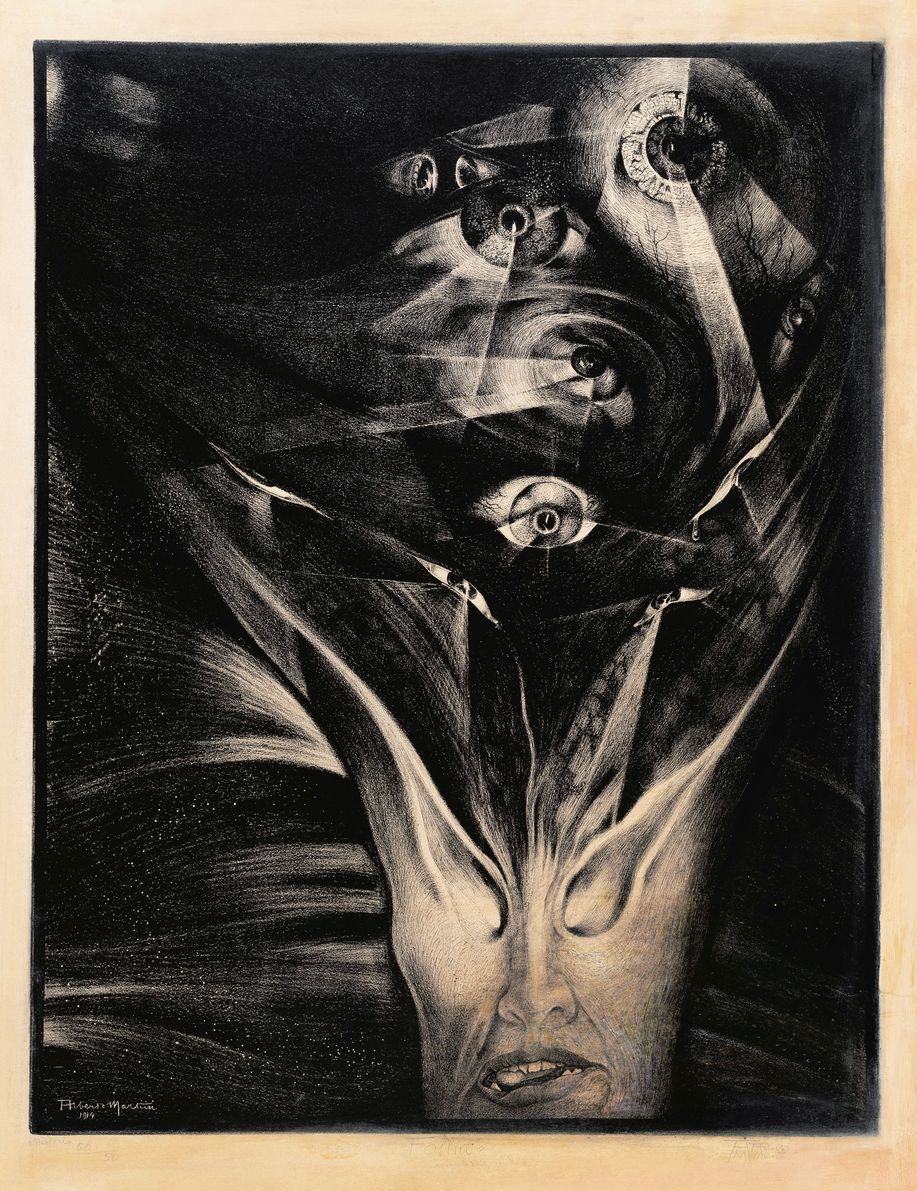

Welcome to the curious world of Artist Alberto Martini, an obscure original visionary and precursor of surrealism. An illustrator, painter, sculptor, propagandist, and possessor of the graphic macabre. He would go on to influence an art movement, visualise the dark and grotesque for Edgar Allan Poe, and journey to the depths of the underworld with Dante. Lets climb inside the mind, with the arctiect of the surreal.

‘The large window of my studio is open onto the night. In that black rectangle, I see my ghosts pass and with them, I love to converse. They incite me to be strong, indomitable, heroic, and they tell me secrets and mysteries that I shall perhaps reveal to you.’

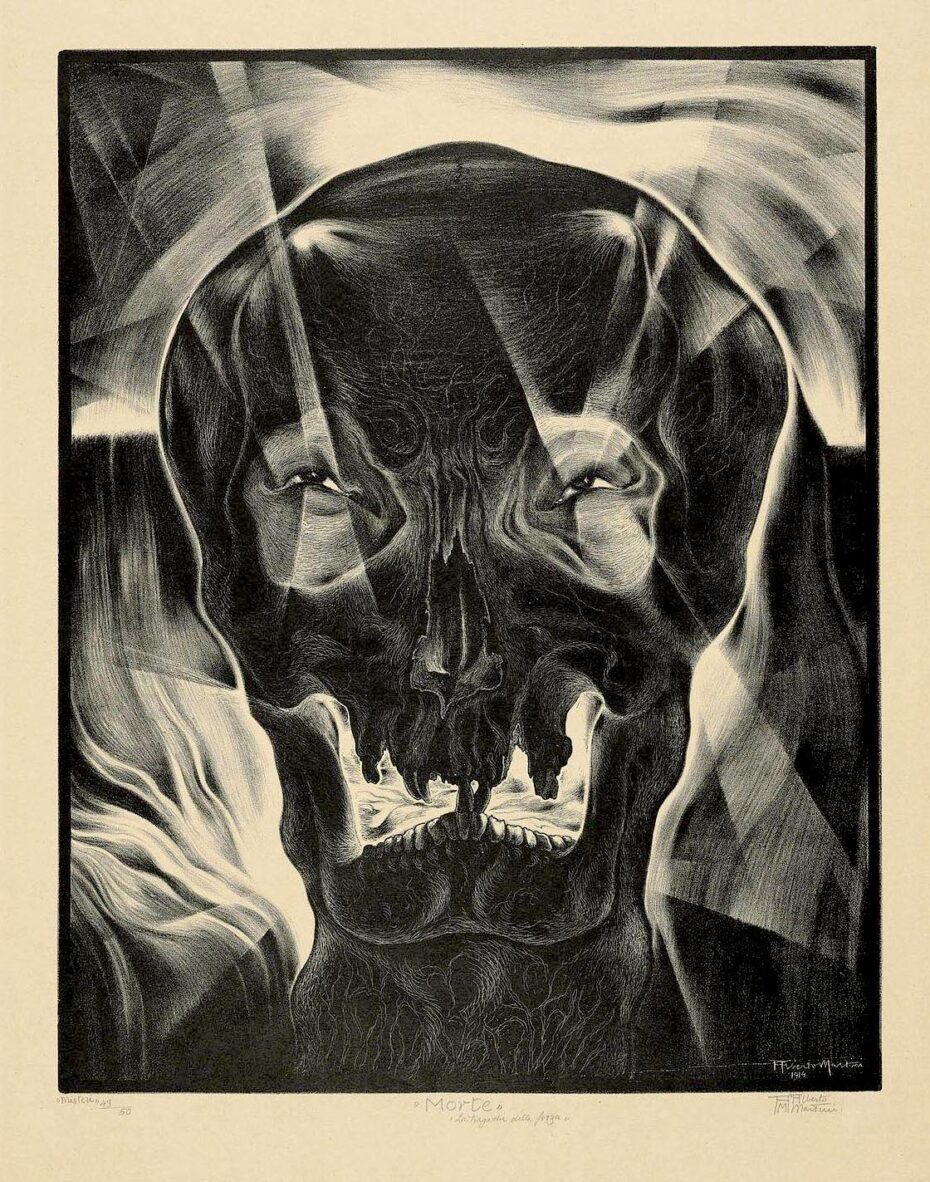

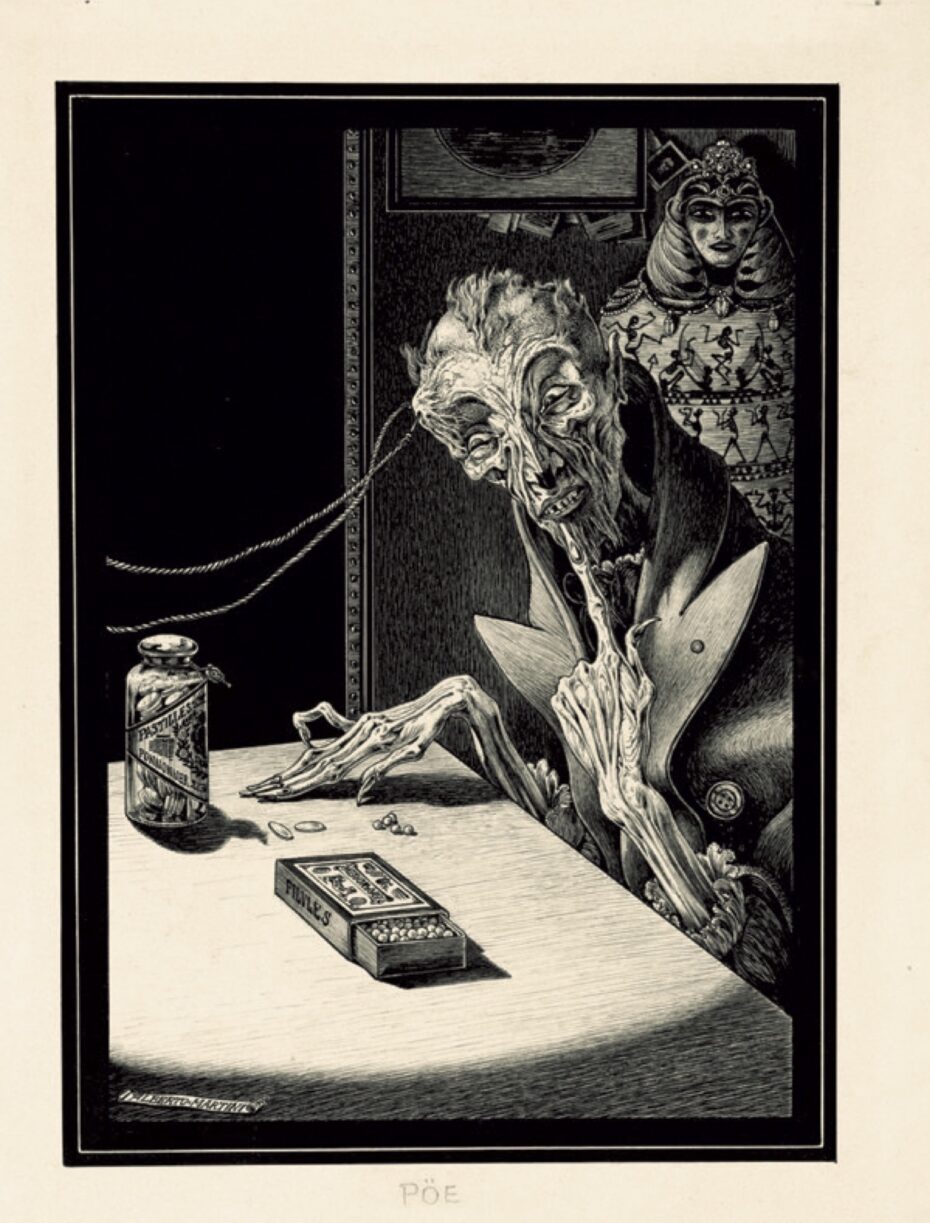

Alberto Giacomo Spiridione Martini would learn his draughtsmanship and artistry from his father Giorgio, a professor of drawing at the Istituto Technico in Treviso. For his surrealistic visions he had to go somewhere deeper. Born in Spain in 1876, he would train in all the typical techniques and mediums of classically trained artists of the time; watercolour, oil, pastel, and ink. He would refine his style in his 20’s moving toward a Manneristic graphic style with suggestions of symbolic entities relating to the Renaissance artists. Martini’s first significant commission would be to interpret and visualise the short stories of Edgar Allen Poe in 1905. This would develop his graphic style and let him reach to the shadows of his subconscious. His pen and ink monochromatic stylistic approach he conjures for the Poe series is probably the most iconic of his works and something he would stay with and develop for some time. He worked on the Poe commission until 1909 completing over 132 ink illustrations. An intensely productive period for Martini, and something that would bring him attention from publishers, and the art world.

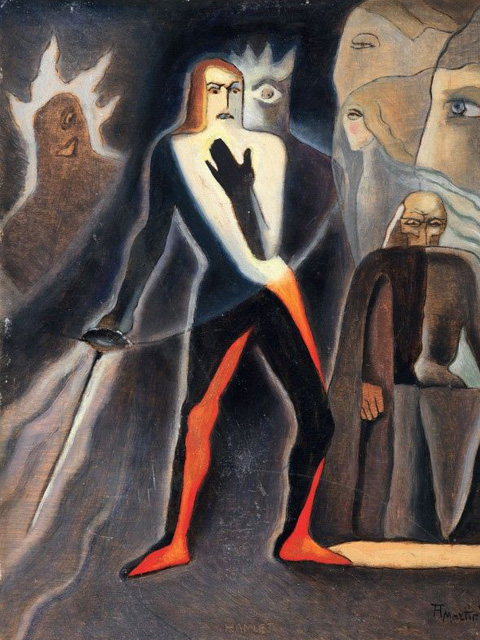

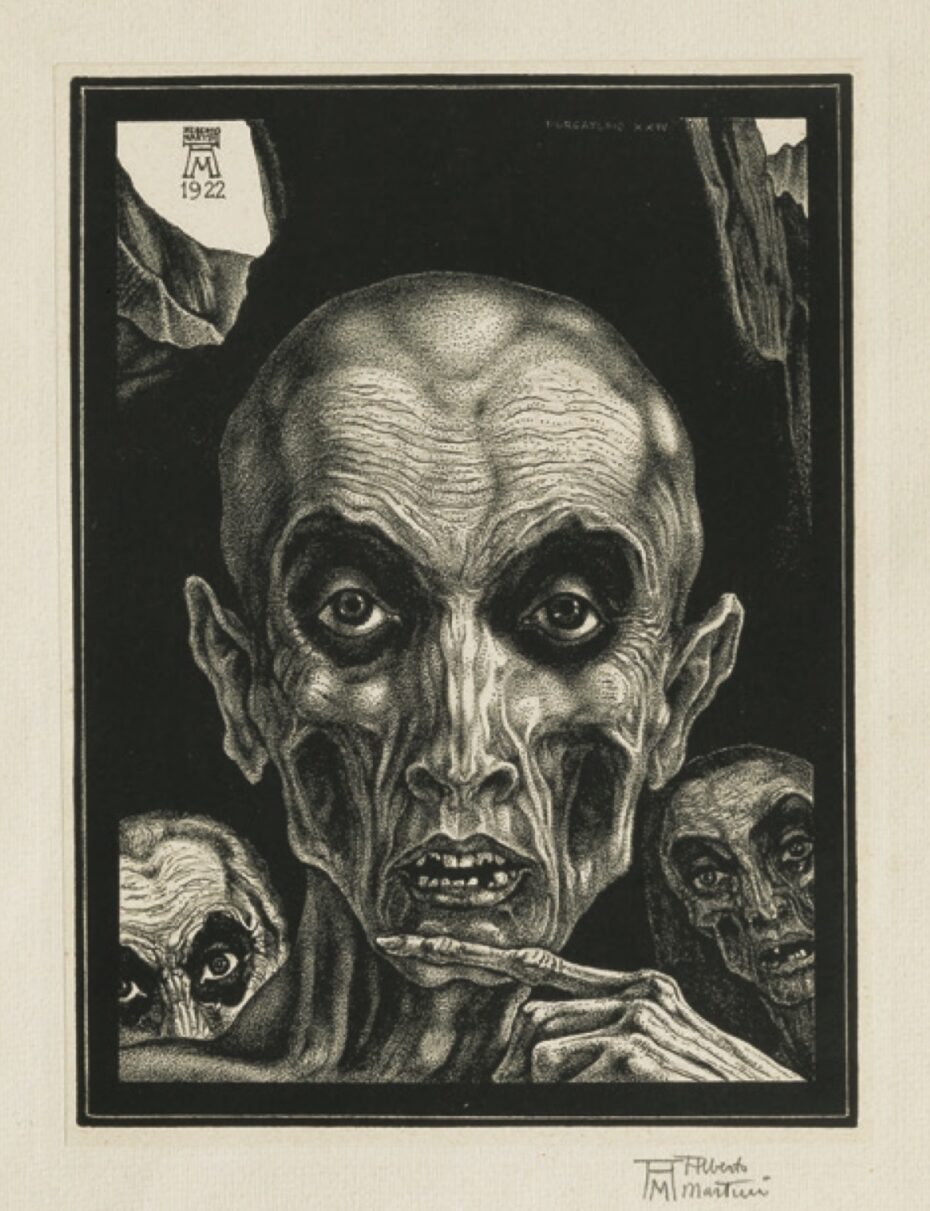

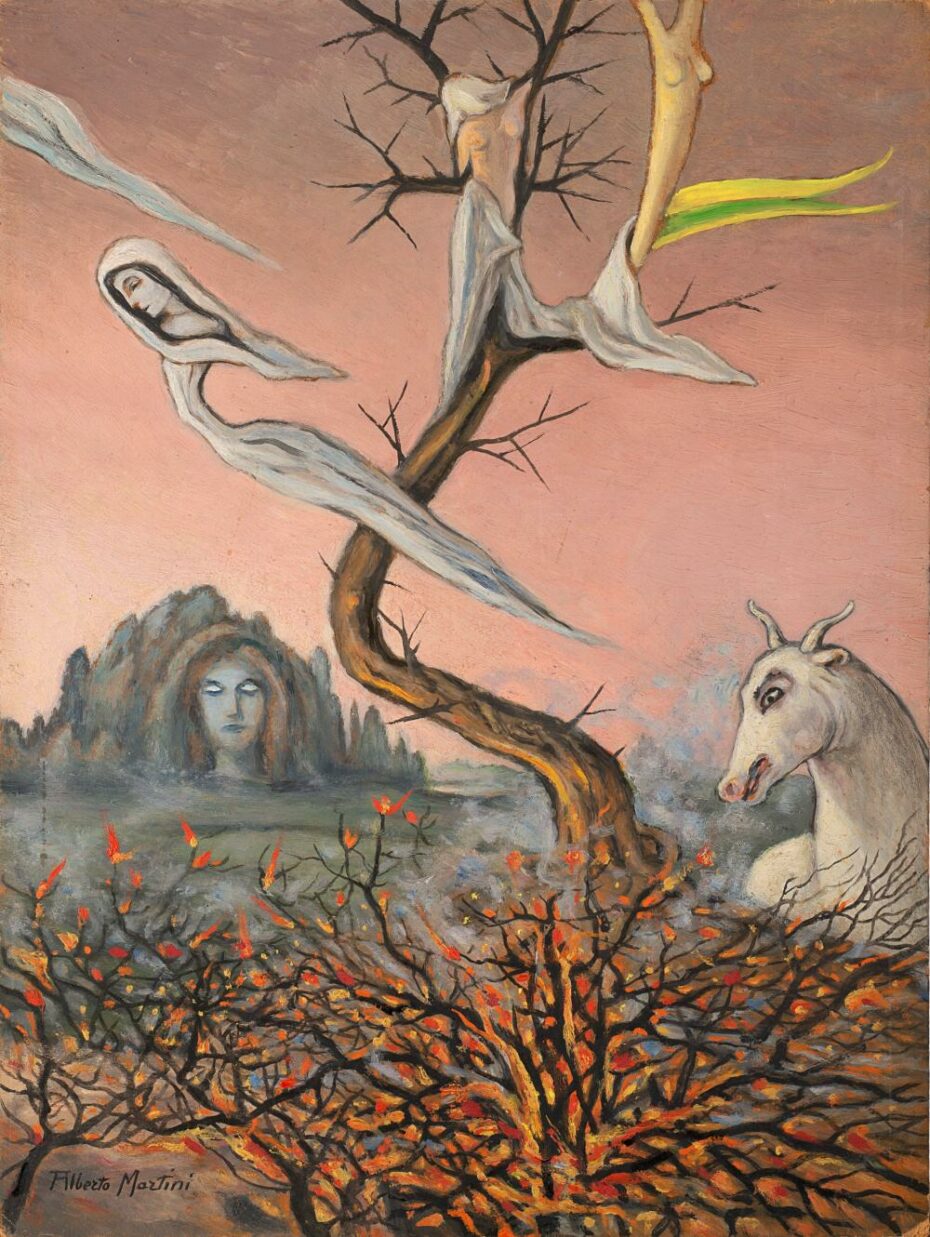

He had shows in London, Berlin and Paris before moving to Italy to seek seclusion in a house in the country and work on commissions for Shakespeare’s Hamlet and poems for Paul Verlaine. In Italy, Martini had his first dalliance with proto-surrealist leanings. He relinquishes the monochrome approach and dials in the colour; ink is exchanged for oil pastels and paint. His work at this point has reached a resplendent ethereal surrealism; echoes of William Blake are seen in his use of this medium and approach. And like Blake, he would illustrate Dante’s Divine Comedy, and join the likes of Salvador Dalí, Paul Gustave Dore, and Sandro Botticelli who would attempt to visualise Dantes epic poem of his journey through the afterlife.

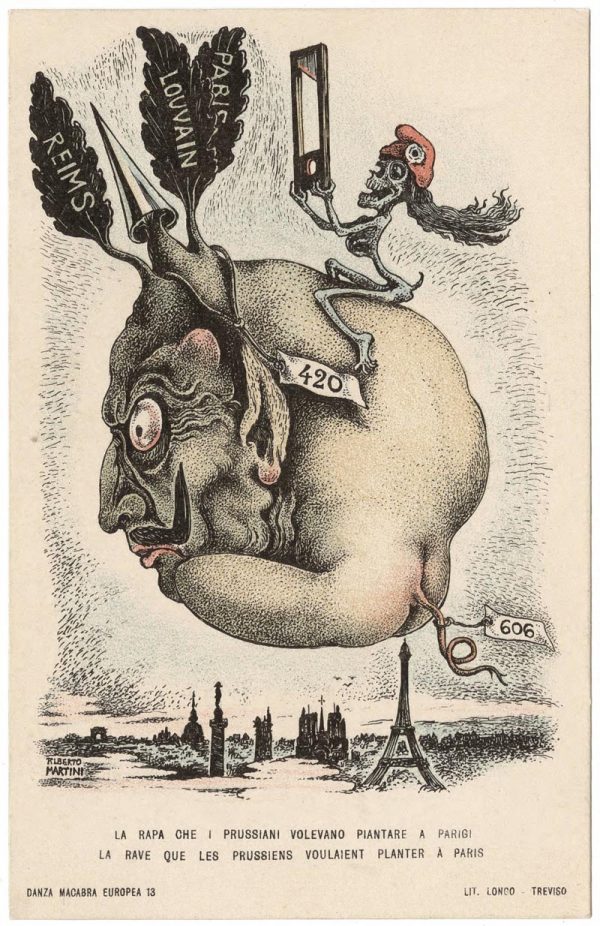

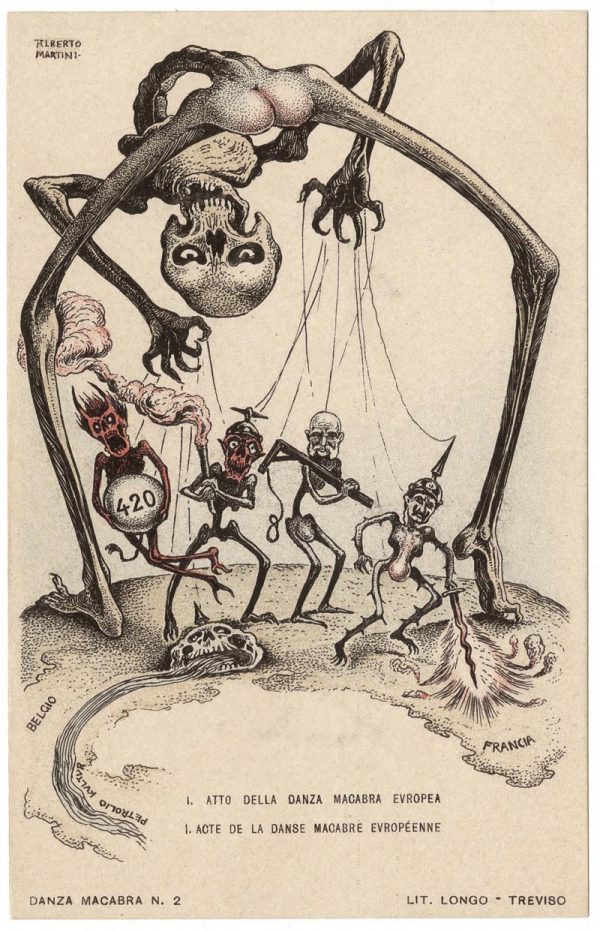

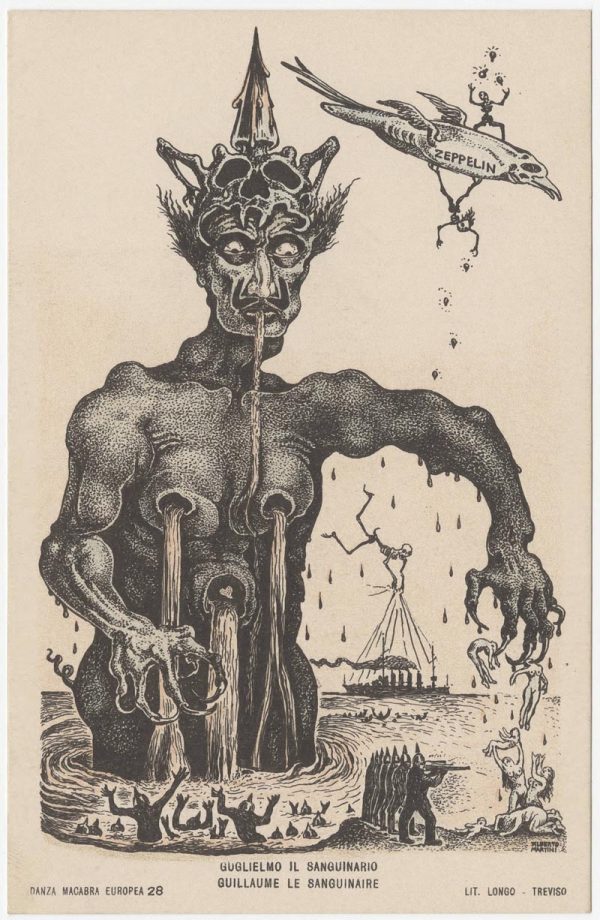

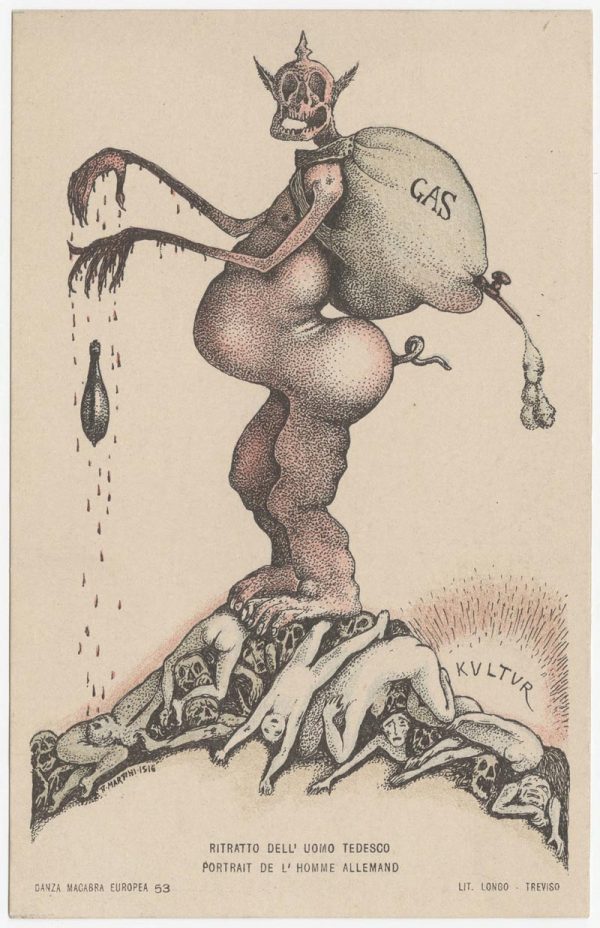

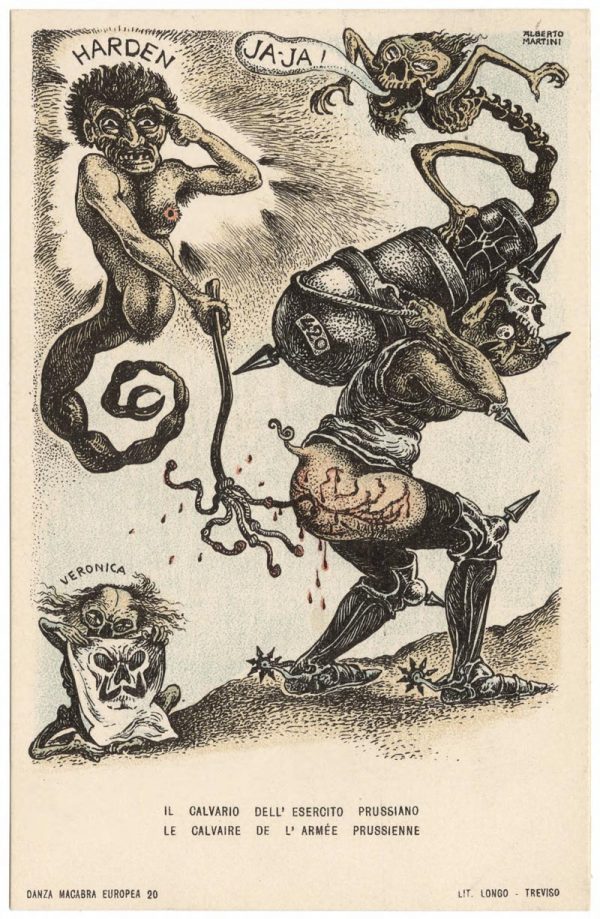

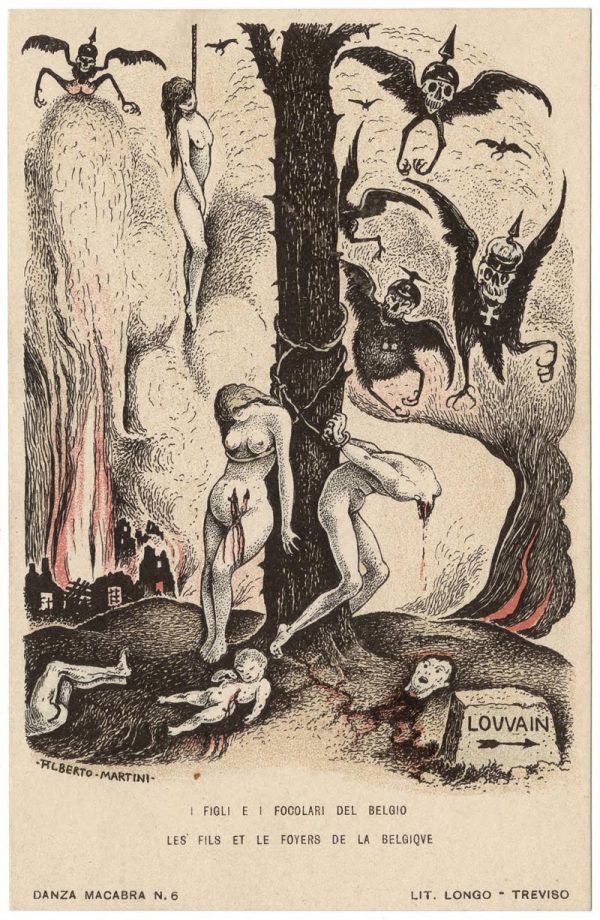

The Beginning of World War I would see Martini dragged from his polychromatic musings and plunged back into the inky black of propaganda Illustration. Martini’s Danza Macabra Europea series sees his work at its most graphically disturbing. Five sets of propaganda postcards were produced and distributed to the troops in the trenches on the front line; a satirical bludgeoning of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Emperor Franz Josef. There were 54 lithographs produced in all and these satirical illustrations would be recognised as some of Martini’s best and most influential. Later surrealists and satirists have no doubt been influenced by the Danza Macabra series; Ralph Steadman and Robert Crumb among them. The grotesque nightmarish quality, seems to go past the point of propaganda and tunes into the depravity of war, the trenches and hopeless slaughter that the troops were facing on the front lines of the ‘Great war’ with this series.

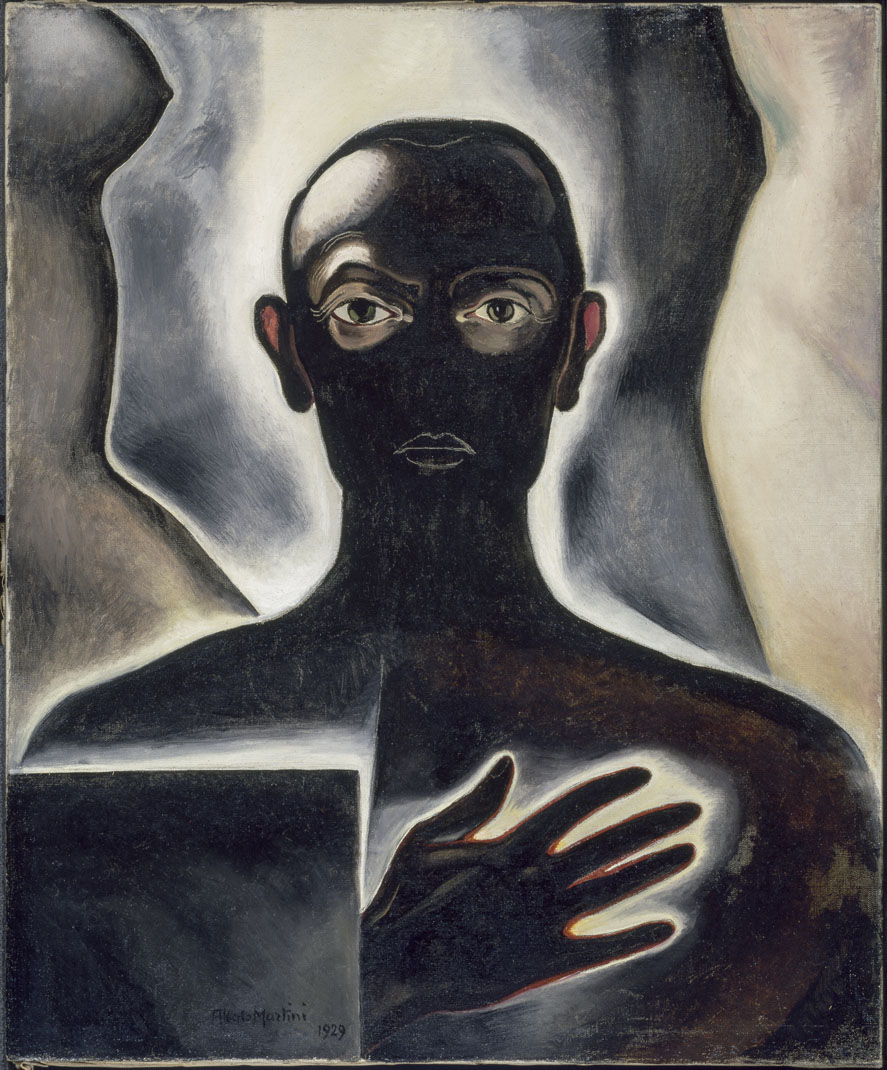

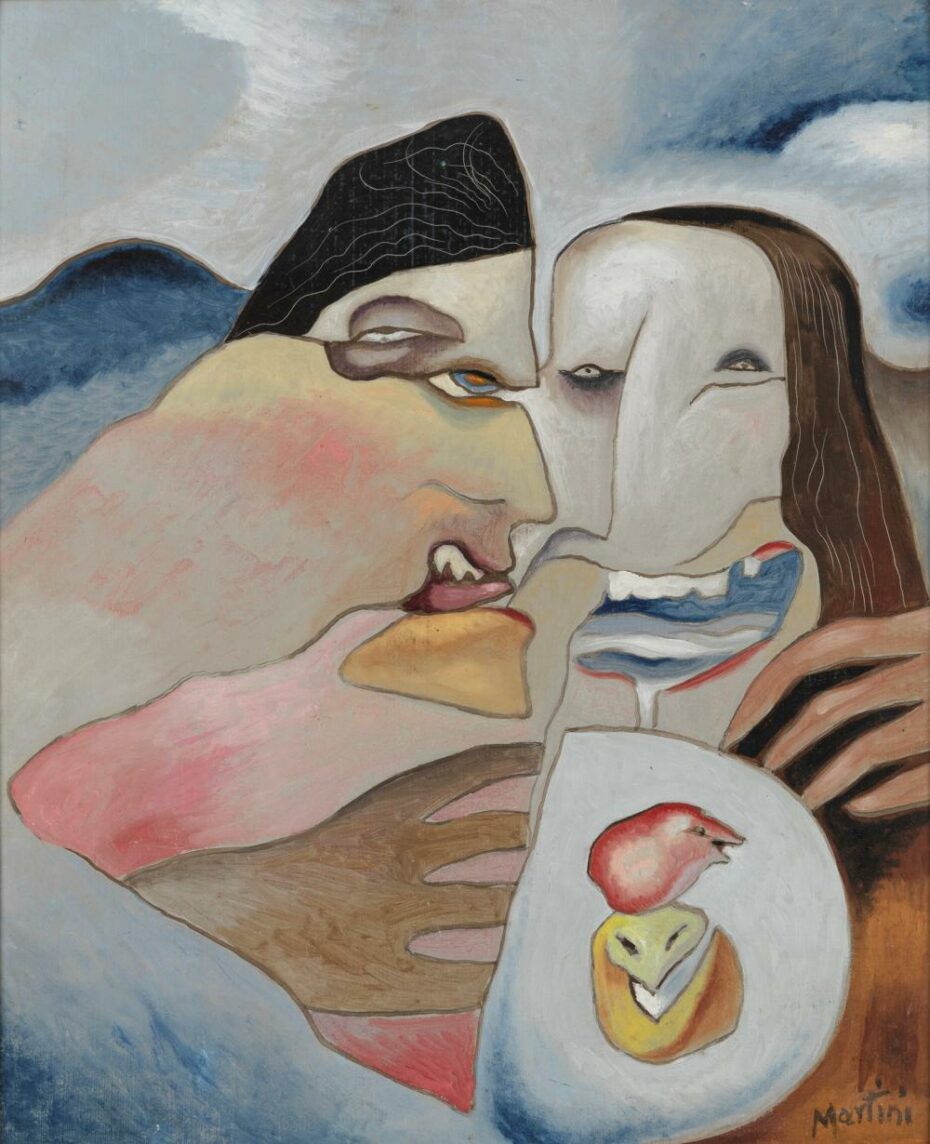

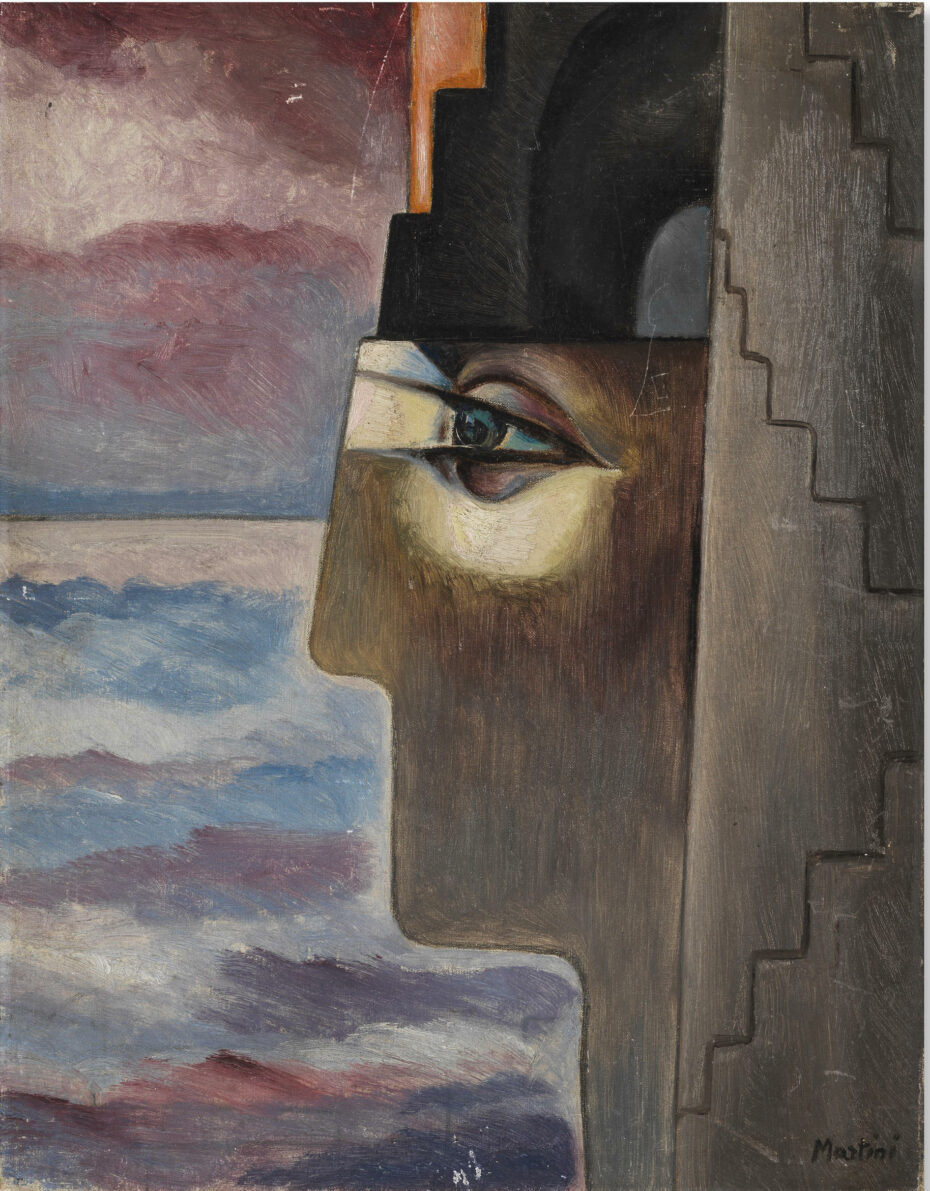

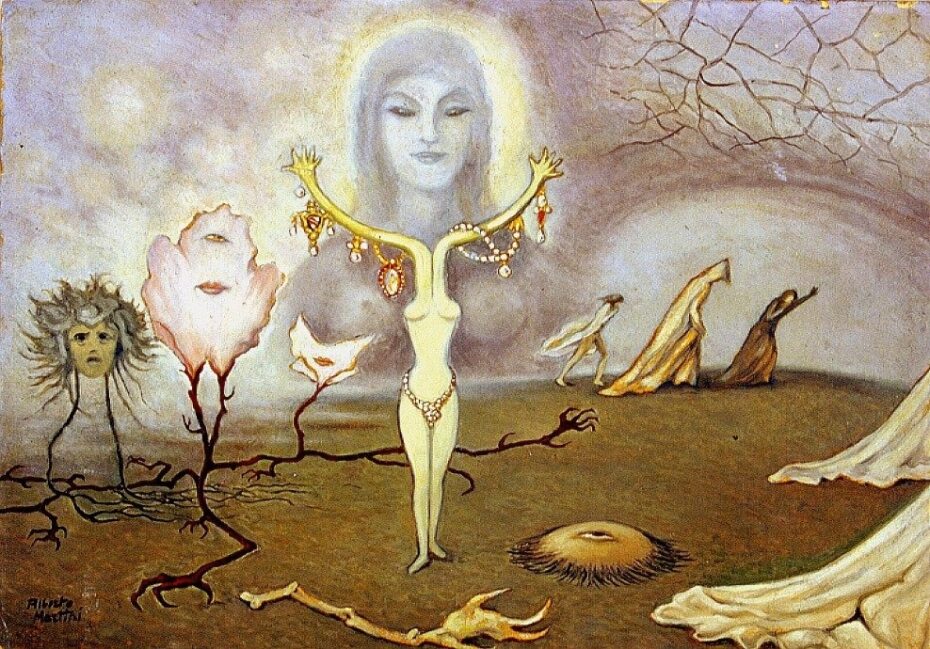

Martini continued to illustrate and produce graphic work for publishing, with marginal success in Italy and decided to move to Paris in 1928. There he would evolve his Surrealist his work from this period onwards. There is an essence of Dali and Picasso around some of the work here; the melting pot of culture that was Paris in the 1920’s clearly having its effect on his work, which would be titled paintings with the colours of the sky; a dreamscape he invented of figurative deformation and colour blending to produce some of his most fantastical work.

He would stay in Paris until 1934, then return to his wife in Italy. Martini continued to paint and develop his work and illustrated a book of by the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, and produced a satirical journal, called Perseus. Success and notoriety always seemed just out of reach to the artist though and his last years were spent exploring the phantom world that he had glimpsed years earlier. He died in 1954, largely unrecognised and yet he remains one of the definitive architects of the surrealist movement.

‘I turned my head and saw a large nocturnal butterfly sitting next to my hand, looking at me, flapping its wings. You too, I thought, are dreaming; and the spell of your dull eyes of dust sees me as a ghost. Yes, nocturnal and beautiful visitor, I am a dreamer who believes in immortality, or perhaps a phantom of the eternal dream that we call life’.