In a world rife with lifestyle influencers and “content houses,” where building one’s own notoriety is big business, it’s tempting to dismiss being famous for being famous as the most banal and basic kind of renown. But there was a time, with a burgeoning American press beginning to define itself and a brash and pithy President occupying the White House, when a young woman from New York with a pedigreed name and an acerbic wit but no particular talent, practically invented celebrity as we know it. She did so at first by smoking on the White House roof or wearing a pet snake draped around her arm at parties, but later with an adept diplomacy that gave credit to the U.S. on the international stage.

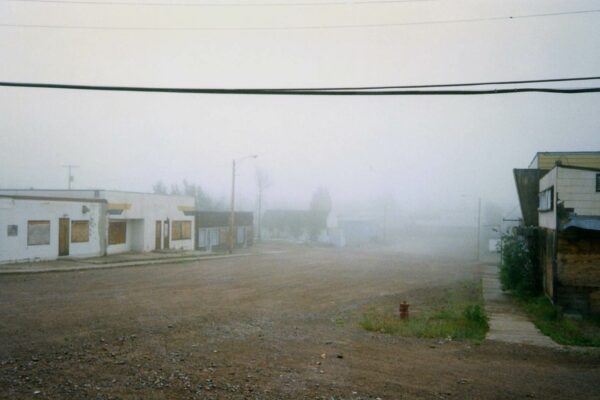

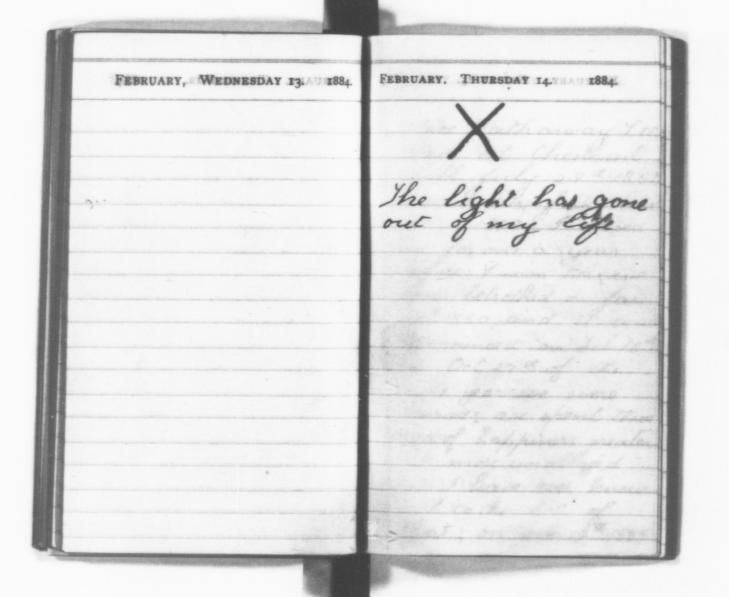

Alice Lee Roosevelt was born on February 12, 1884. Two days later, her mother, also named Alice, succumbed to kidney failure. On the same day, Alice’s paternal grandmother died of typhoid fever. Alice’s father, politician and future president Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, wrote in his diary on that tragic Valentine’s Day, “The light has gone out of my life.” Unable to manage his grief, T.R. effectively abandoned his infant daughter into the care of his older, unmarried sister, Bamie, as he quit politics and fled to his cattle ranch in the Dakota Territory. For the rest of his life, Teddy refused to speak to Alice of her mother and disliked even the mention of her name. The wound of being motherless and nearly fatherless with a name unspeakable to her own family would shape many of the escapades that defined Alice’s legacy.

Almost three years after his first wife died, T.R. returned to New York and married his childhood sweetheart, Edith Carrow. The couple took Alice back into their home, though it was not exactly a happy reunion for the young girl. Edith was a cold and detached woman with strict standards of proper conduct who once wrote of Alice that she would not do anything unless she was made to. Alice, meanwhile, felt that her stepmother only wanted her as part of the family as a religious obligation and that her father ignored her to assuage his own guilt:

“My father obviously didn’t want the symbol of his infidelity around. His two infidelities, in fact: infidelity to my step-mother for marrying my mother first, and to my mother for going back to my step-mother after she died.”

Alice was soon joined at the Sagamore Hill estate by five half brothers and sisters. The family almost exclusively referred to Alice as “Sister” to avoid reminding her father of his first wife. It’s hardly any wonder that a defiant Alice would seek to make a name for herself on her own terms.

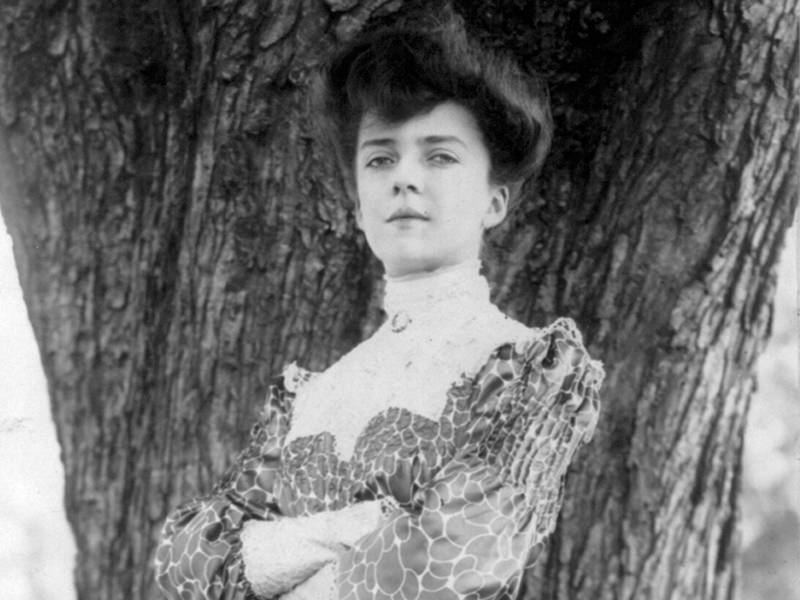

Opportunities for young women at the turn of the 20th century were strictly guided by the principles of Victorian morality, in which ladies were expected to be restrained, demure and industrious. Alice was none of these things. Her stepmother lamented that Alice was a “guttersnipe” who “cares neither for athletics nor good works” and that she had a “habit of running the streets uncontrolled with every boy in town.” Her exasperated father wrote to Bamie, “I am sure she really does love Edith and the children and me; it was only that running riot with the boys and girls here had for the moment driven everything else out of her head.” When her father threatened to send her off to a strict boarding school to tame her behaviour, Alice spat back that she would “do something really disgraceful.”

Up to that point, despite her society upbringing and her father’s political career, Alice’s antics remained largely a private affair. But in 1901, Teddy Roosevelt became vice president; in September of that year, he assumed the presidency after William McKinnley was assassinated. The Roosevelt clan moved into the White House with a veritable zoo, including a bear named Jonathan Edwards, a variety of guinea pigs, a lizard, a badger, a hyena, a barn owl, various other birds, a pony and Peter the rabbit. Alice brought with her a pet garter snake named Emily Spinach, “because it was as green as spinach and as thin as my Aunt Emily.” Some even counted Alice herself among that mad presidential menagerie, with a friend of Edith’s describing Alice as “like a young wild animal that had been put into good clothes.”

The nation and the press were captivated by this young, rambunctious family occupying the White House and their quirky hijinks – rollerskating in the East Room, popping out behind vases to scare visiting dignitaries, stilt walking through the hallways and sliding down banisters. In fact, the children were so disruptive that they prompted the construction of a separate presidential office – the famous West Wing – simply so their father could get some work done. Not that this deterred Alice in the least. During one Oval Office meeting, Alice interrupted so many times that her irritated father threw up his hands and proclaimed, “I can be President of the United States — or — I can attend to Alice. I cannot possibly do both!”

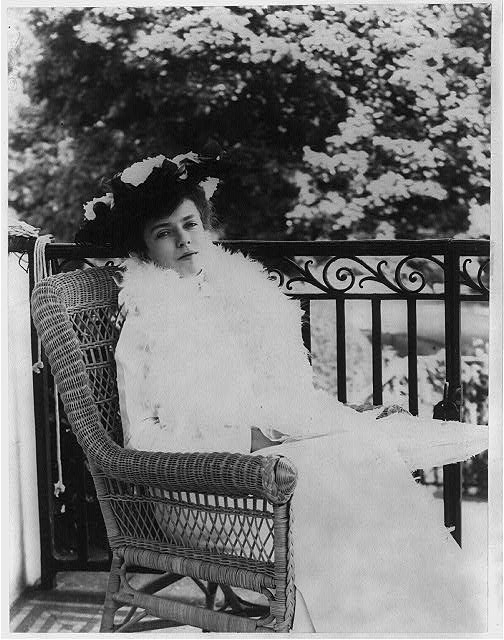

America’s obsession with all things Alice began in earnest with her society debut in January 1902. The festivities had been impeccably timed during the holidays to ensure as many eligible young bachelors as possible could attend without interrupting their university schedules, and Alice’s debutante ball was one of the first major social events hosted by the Roosevelt White House. The United States Marine Band provided the musical entertainment for more than 600 high-society guests, and the New York Times declared the evening “one of the most charming social events Washington has ever known.” The press went wild for the first White House debutante in more than 25 years, and audiences devoured the detailed coverage of every aspect from Alice’s dress to the decor. “There was no Hollywood and there were no movie stars in those days,” Alice said in later years of the intense public interest in her life. “They liked my father and there was I having a good time and not really giving a damn.” While an adoring public found the ball fascinating, Alice remembered it differently. She and Edith had a row over the arrangements, with Alice raging that she wasn’t allowed to serve champagne, and she called her own gown “a singularly repulsive white number—I would have preferred to wear black.”

From that moment, Alice’s name, likeness and escapades sold not only newspapers but postcards, songs and dresses, too. “Alice blue,” a steely, pale gray blue created to evoke the color of Alice’s eyes, became a fashion sensation, while songs like “The Alice Roosevelt March,” “Alice Roosevelt Waltz,” and “Alice Blue Gown” were named in her honour.

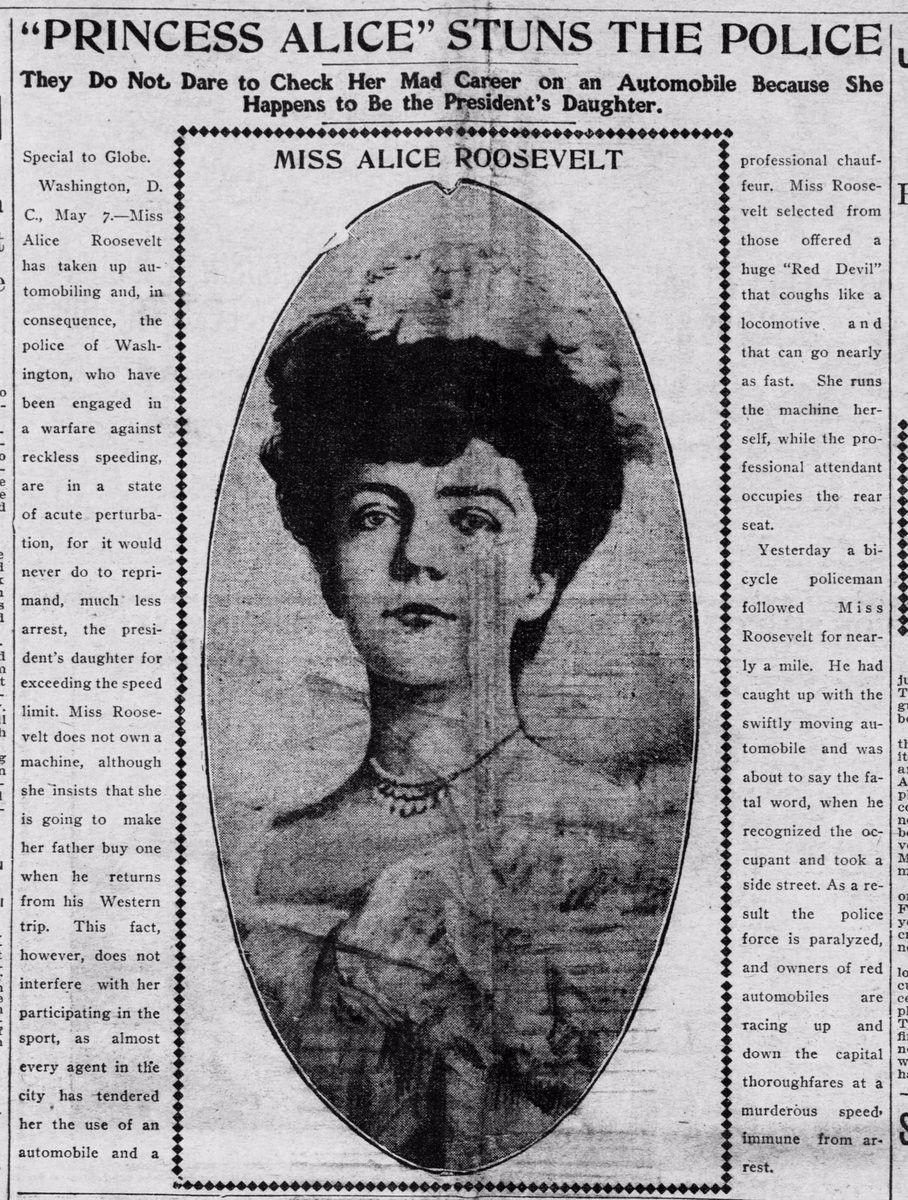

Teddy frequently chided his daughter for courting publicity, though she shot back that he had to be “the bride at every wedding and the corpse at every funeral.” When her father sent her scorching letters of reprimand, she promptly tossed them into the fire. And while celebrity found Alice whether she courted it or not, no one could accuse her of being changed by fame. She was utterly and thoroughly herself no matter how many pages the press dedicated to her. She raced through the streets of Washington in her own car, always unchaperoned and often accompanied by multiple young men. She wore trousers and makeup despite both being considered improper, and she was photographed placing bets and picking up her winnings at horse races. When Alice took up smoking, Teddy declared that no daughter of his would smoke under his roof. The ever-obedient Alice instead climbed up to smoke on top of the White House roof. A Los Angeles school superintendent even blamed Alice for creating a fad for cigarettes, which had “a demoralizing effect on the women of this country.”

A month after Alice’s debut, she was catapulted to international renown when she christened a yacht belonging to German Kaiser Wilhelm. Alice stood holding the arm of the Kaiser’s cousin Prince Henry of Prussia and broke a bottle of champagne against the bow, much to the chagrin of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. (Owing to Alice’s habit of bringing whiskey to dry parties, she was hardly a favourite of the Union anyway.) The New York Time said Alice was “the most self-possessed person on the stand, and seemed to look upon the whole affair as a lark.”

Speculation swirled that Alice would be married off to some European royal, and the First Daughter was dubbed Princess Alice by the press. The American “princess” soon came into rare public criticism thanks to the moniker she never chose as certain corners of society felt there was too much of a royalist leaning to her treatment for the staunchly anti-monarchist U.S. Indeed, even other governments persisted in treating Alice as “a daughter of the Government” and an official representative of the nation. The scandal, fuelled entirely by newspaper reports, reached its zenith when Alice received an invitation to the coronation of Edward VII.

“The press got very silly,” Alice recalled, “and started wondering whether my aunts were going to be my ladies-in-waiting.” To avoid any appearance of undemocratic sympathies, Alice was forced to decline the invitation, and her father sent her to Cuba instead. Her popularity there, despite Alice not acting in any official capacity, seemed to give the President an idea. If he couldn’t control his daughter or the press, perhaps he could wield both to his advantage.

In 1903 Alice visited Puerto Rico, undertaking the kinds of public relations-activities for which visiting dignitaries are often called upon – witnessing troop reviews, laying cornerstones, attending receptions and naming a fire engine. “I was on my best official behavior,” Alice declared. Teddy was pleased by her performance, writing to her on her homecoming, “You were of real service down there because you made those people feel that you liked them and took an interest in them and your presence was accepted as a great compliment.”

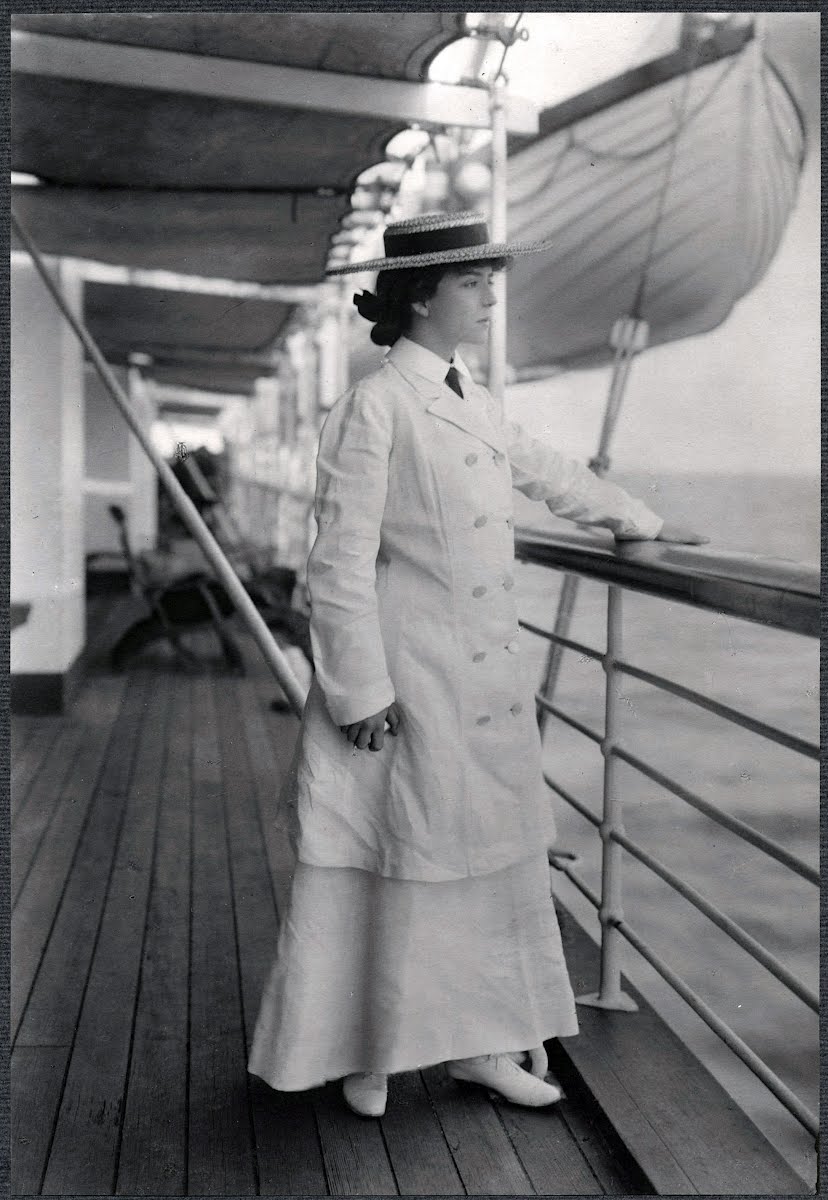

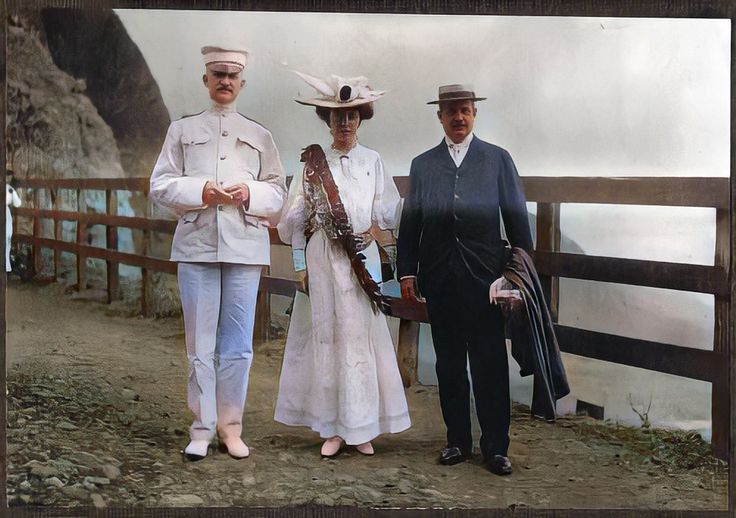

As the President negotiated a peace agreement at the end of the Russo-Japanese War, he sent a large peace delegation to tour Asia. Right alongside Secretary of War. William Horward Taft, was Alice Roosevelt, sent to demonstrate her father’s interest and trust in the countries and people they visited. Alice brought so much luggage and changed clothes so many times a day that her maid, Anna, nearly had a nervous breakdown “and for three days while we were at Manila, was sent to take a sort of rest cure on the Government Transport.”

If President Roosevelt thought getting his daughter away from Washington would tame the press and refocus public attention on himself, he badly miscalculated. On the train from D.C. to California, Alice celebrated Independence Day by setting firecrackers off from the back platform and firing a revolver at telegraph poles. In San Francisco, she slipped away from her chaperone to explore Chinatown alone. In Hawaii, she begged the locals to show her “real” hula instead of the sanitised, tourist version put on for the official party. “Afterwards a song was written that ran as follows: ‘Alice Roosevelt, she came to Honolulu and she saw the Hula Hula Hula Hai, and I think before she reached the Filipinos, she could dance the Hula Hula Hula Hai,’” Alice wrote. “I could and did.”

Taft begged reporters not to publish photos of Alice in her bathing suit while swimming and surf boating at Waikiki, though as Alice herself pointed out, bathing suits of the time were high-necked, long-sleeved dresses worn complete with stockings. She applied the same logic while sailing for Japan on board the Manchuria when she jumped into the swimming pool fully clothed in a linen skirt and shirtwaist and goaded her friend Bourke Cockran into doing the same.

All across Southeast Asia, Princess Alice was received by royalty and treated as such everywhere she went. When visiting the imperial family at the Chinese Summer Palace, she was carried in a golden litter on the shoulders of four attendants, and reportedly the Sultan of Sulu proposed to her. The American ambassador to Japan turned down an invitation for Alice to stay at the Japanese royal palace to avoid any hint of impropriety, and Alice’s already unwieldy luggage was supplemented with the lavish gifts she received at every port. From pearls to bolts of finest silk, jade and gold jewellery, examples of local dress, and even a little black Pekingese from the Empress Dowager of China, Alice collected so many precious gifts that her friend Willard Straight called her ‘Alice in Plunderland’. Her father admonished her to only bring home those items she truly wanted because she would have to pay the duties herself.

But the other souvenir Alice brought back from the trip was what the country had been waiting for with baited breath: a fiancé. The papers had speculated on who Alice might marry from the moment of her debut, and in the end it was Nick Longworth, a congressman from Ohio and part of the Asian delegation, who won her hand. At 15 years her senior, the short, balding and bland Longworth hardly seemed a natural choice for the vivacious and outrageous Alice. But he was wealthy and ran in the right circles for her father to approve. Alice later admitted that she chiefly married only to get away from her father and stepmother. While the marriage was not a happy one and both Alice and Longworth would go on to have affairs (Alice’s daughter Paulina may in fact have been fathered by her long-time lover, Ohio senator, William Borah) the wedding day itself was hailed as a fairytale. To ensure no one could possibly upstage her, Alice refused bridesmaids. Every newspaper in the country dedicated pages and pages to Alice in the lead-up to the anticipated event, from speculation on her wedding dress to tallies of the spectacular gifts arriving from well-wishers and foreign royalty. Police were forced to intervene for crowd control when Alice went shopping in New York to fill her trousseau before the wedding. Crowds lined the streets around the White House on the day of the wedding to catch a glimpse of the bride. At the wedding breakfast, Alice dramatically sliced the wedding cake with a sword she demanded to borrow from a military aide. As she prepared to leave the White House and thanked her stepmother for the wedding preparation, Edith said bitingly, “I want you to know that I’m glad to see you go. You’ve never been anything but trouble.”

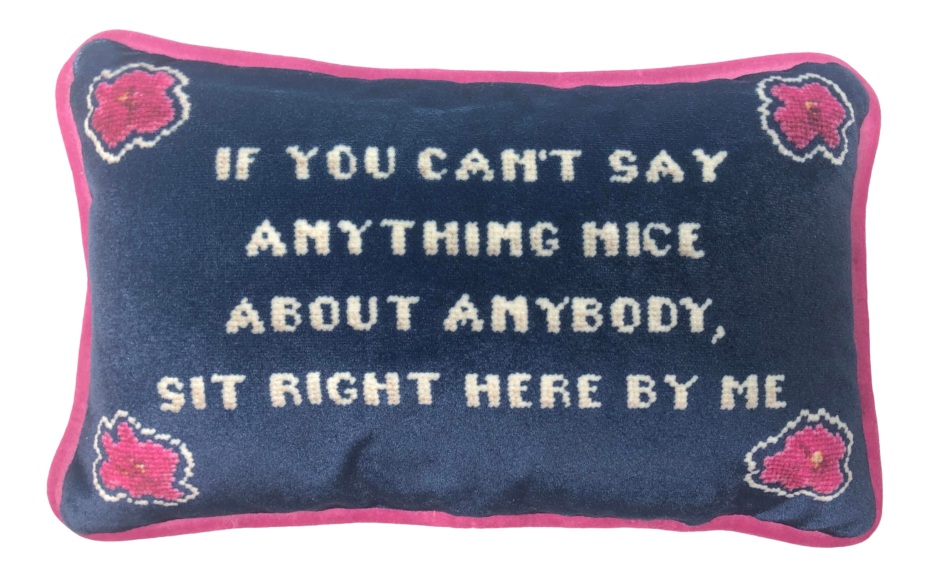

Her marriage may have ended her time at the White House, but her career as “an ambulatory Washington monument” was only beginning. When Taft succeeded Roosevelt as President, Alice buried a voodoo doll of incoming First Lady Nellie in the front yard and went about at parties doing an impression of Nellie’s “hippopotamus face.” Her behavior earned her a ban at official White House events, and not for the last time. Woodrow Wilson similarly barred her from the property for telling bawdy jokes about him. Alice’s sitting room received a constant stream of visitors looking for tea, gossip and introductions – the ingredients of Washington power. Alice knew just how to mix the right people with the right ideas to wield that power and influence candidates and congressional bills. And all of these powerbrokers were greeted in Alice’s Embassy Row sitting room with a pillow that read, “If you can’t say something good about someone, sit right here by me.”

Alice vehemently criticized her cousin Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal policies (she referred to FDR himself as “two parts mush and one part Eleanor”) and was a staunch isolationist, lobbying through the America First organisation to maintain neutrality in World War II. She was bored of Dwight Eisenhower but found the Kennedys fascinating and got on exceedingly well with Richard Nixon, who attended Alice’s 90th birthday party in the midst of the Watergate scandal. Indeed, conversations with Alice feature in three of the secret Nixon White House tapes, which came to light during the Watergate congressional hearings.

Alice held court in D.C. until the age of 96, outliving her husband, her daughter and most of her friends, but never losing her wit or her influence on society and politics. When reflecting on her Washington life she quipped, “I would have found anything else rather dull in comparison.”

For all the things Alice may have been called – from guttersnipe to princess – dull was never one of them.