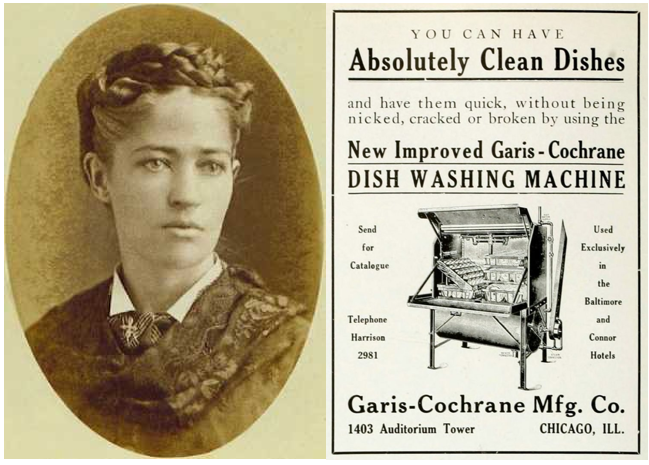

As the saying goes, necessity is the mother of invention. Case in point: there’s a certain 19th century American housewife and single mother we should thank for giving us the mechanical dishwasher. You’ve probably never heard of her but Mrs. Cochrane forever changed the landscape of household chores and revolutionised the kitchen. Fed up of chipping her precious china when washing up, and faced with the pressure providing for her family, she decided, “If nobody else is going to invent a dishwashing machine, I’ll do it myself”. In 1926, her company was bought by KitchenAid which later became part of the household-name Whirlpool Corporation. Let’s meet Josephine…

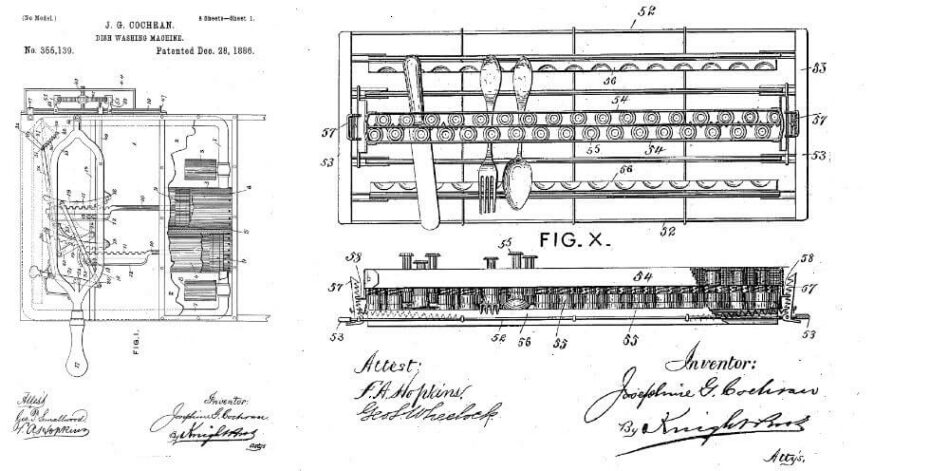

After her husband’s unexpected death in 1883 following his long struggle with alcoholism, Cochrane was left with a whole lot of his debt and little choice but to turn her ideas into something profitable. Hailing from the Midwest, Cochrane was born into a family of tinkerers, with a civil engineer father and a grandfather known for having first patented the steamboat, but she had never received a science education. Setting up a workshop in her back shed, the widowed mother of two collaborated with local mechanic George Butters to build a prototype, filing her first patent application in December 1885 for the “Cochrane Dishwasher.”

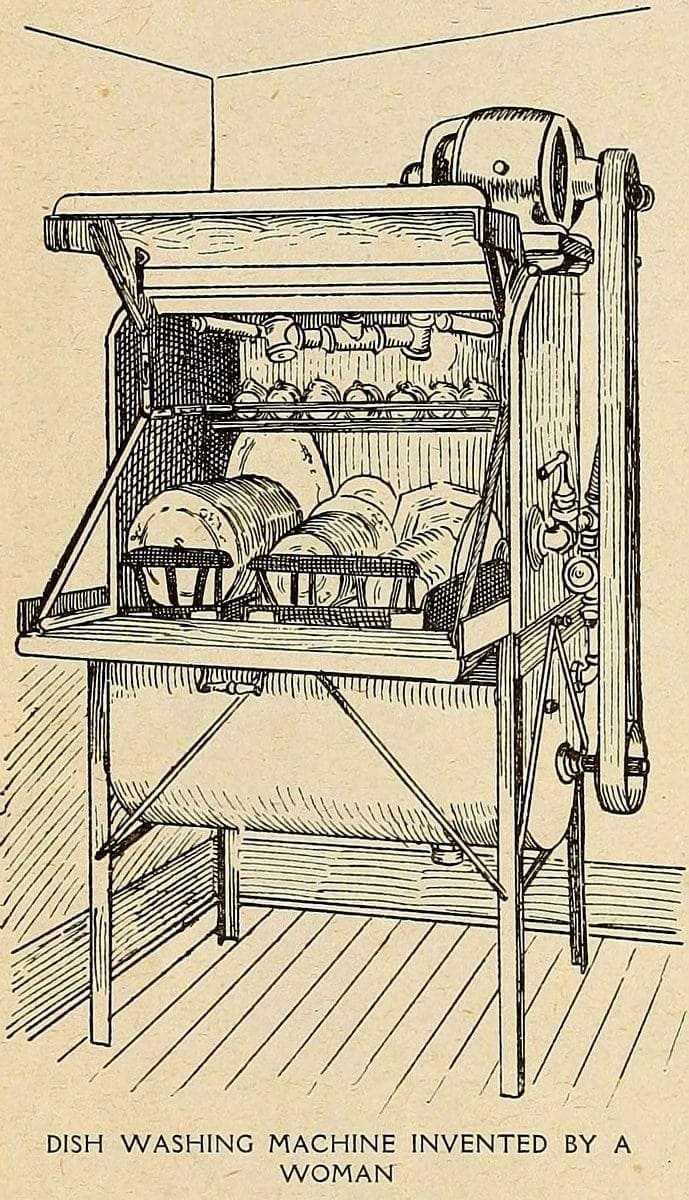

There had been previous attempts to introduce the world to a successful hand-powered dishwasher. Joel Houghton had designed a dish soaker using a hand crank back in 1850 and a decade later, L. A. Alexander built on the prototype by adding a gear mechanism so dishes on racks could rotate through a container of water. Neither of these inventions were any good. Cochrane measured cups, plates and other cooking wear to design wire compartments, each of which was meant for a specific type of dish. These compartments went inside a wheel inside of a copper boiler. A motor allowed the wheel to rotate as soapy water squirted up onto the dishes. This was the first design using pressure instead of scrubbers to do the cleaning.

While she had accomplished the design aspect of creating a working product, actually selling it would prove to be just as big of a challenge. Costing some $75-$100, it was too expensive for the vast majority of households, and many didn’t have enough hot water in their kitchen for it to work properly. The nascent Garis-Cochran Manufacturing Company focused instead on restaurants and other commercial clients, including the prestigious Palmer Hotel in Chicago. Though as a woman in business, she stood out:

“You cannot imagine what it was like in those days… for a woman to cross a hotel lobby alone,” she told a reporter. “I had never been anywhere without my husband or father, the lobby seemed a mile wide. I thought I should faint at every step, but I didn’t, and I got an $800 order as my reward.”

In fact, she fought off multiple male investors interested in taking the business out from underneath her and forged ahead on her own. The year 1893 would prove to be one of the most critical for Cochrane’s washing machine with the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Hers was the only invention by a woman in the Machinery Hall, which showed off American innovations. She found an even broader range of clients including hospitals and schools interested in purchasing her machines At that point, the industrial model could wash and then dry 240 dishes in two minutes. She won an award for design and durability and more importantly, the washing machine became a household name.

The business, now called Cochran’s Crescent Washing Machine Company, continued to expand across North America, with Cochrane opening a factory in around 1898. Cochrane continued selling her machines well into her seventies until she died of a stroke likely connected to exhaustion in 1913 at the age of 74. But her design continued on: by the 1950s, kitchen advancements and decreased prices meant it was practical for a broader majority of homes to have a dishwasher. And advances in dish soaps meant dishes came out sparkling clean and without any residue, which had been an issue in the past. Cochrane’s business became KitchenAid, which became part of the Whirlpool Corporation portfolio. In 2006, she was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Her ambition to identify and an issue and find a solution can still be inspiring for inventors and inventors-in-training. As Cochrane reflected before her death: “If I knew all I know today, when I began to put the dishwasher on the market, I never would have had the courage to start. But then, I would have missed a very wonderful experience.”