What was once essentially a completely Greek city in the depths of Afghanistan, was lost under the desert sands for almost 2,000 years, hidden from history until its sensational rediscovery in the 1960s. It was christened by archeologists as Ai-Khanoum, or ‘Lady Moon’, after an Uzbek princess who had lived on its rocky summit. But in a land that in the last 50 years alone has been plagued by multiple foreign invasions, civil wars and regimes that seek to eradicate any traces of the country’s non-Islamic past, how has such a momentous and precious discovery fared during its most recent history?

Two thousand odd years ago, Alexander the Great’s ancient Greek empire flashed across the known world, from his unlikely starting point in West Macedonia as far as present-day Afghanistan. In the wake of his military triumphs, so followed the cultural deluge of Greek traders, architects, artists, builders and all things Greek. Three-thousand miles away from the Aegean Sea, the discovery of Ai-Khanoum, a once a glittering cosmopolitan Greek city, proved just how profound, enduring and far-reaching this cultural influence was. “There were Greek, Macedonian and Thracian citizens, who enjoyed the temples, the gymnasiums and the arenas exactly as if they were in a city on the Greek mainland,” wrote Oxford classicist Robin Lane Fox.

Although the French had been excavating in the area since the 1920s, the site of Ai-Khanoum was brought to the world’s attention in 1961 by the-then Afghan King, Mohammad Zacher Chach, who allegedly noticed a fragment of a Corinthian column while on a hunting trip in 1961. Despite problematic politics and funding, a team of French archeologists (Délégation archéologique française en Afghanistan – DAFA) was ultimately entrusted to begin excavating the site officially.

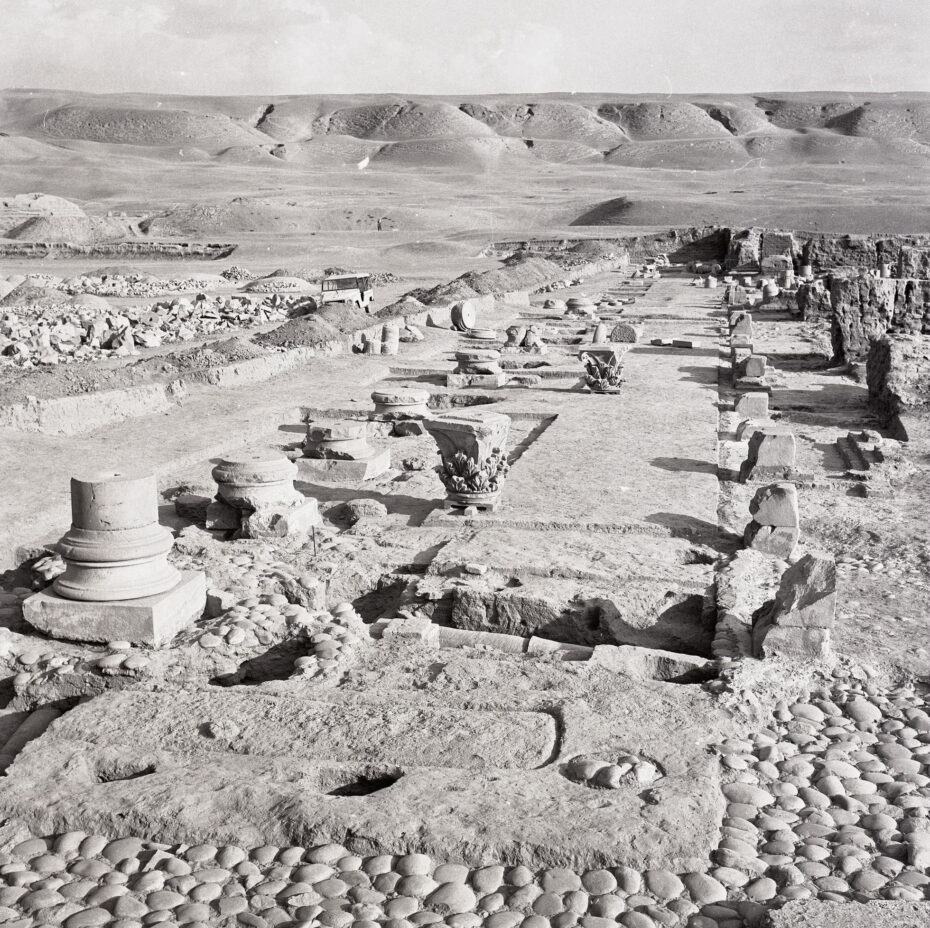

The team exposed a vast, formally planned Greek city, long lost to records, and the city’s original Greek name is still unknown to this day. It had never been resettled or rebuilt after its fall and the original ruins had laid unnoticed and undisturbed for thousands of years close to the surface.

While originally thought to have been founded by Alexander the Great, more recently scholars believe this easternmost Hellenic city was more likely founded by the subsequent Seleucid Empire, a major centre of Hellenistic culture reinforced by steady immigration from Greece. “What is certain is that, two centuries after Alexander the Great, Greek was still spoken [there],” notes Nicolas Engel, head of Afghan antiquities at the Guimet Museum in Paris.

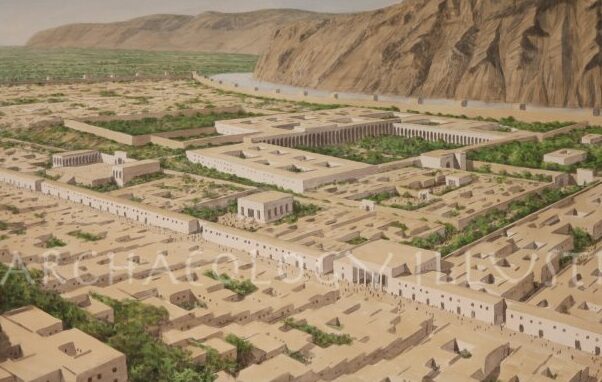

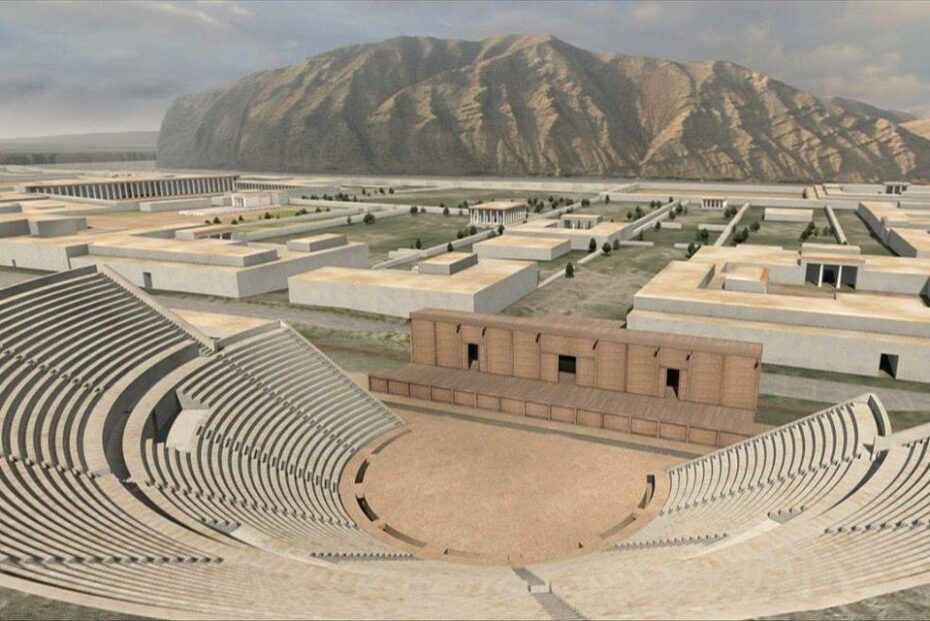

Its architecture, temples and Greek inscriptions revealed how Ancient Greek colonists had created a home away from their true home, Greece. The city’s acropolis had stood on the massive rocky cliff rising beside and protecting the lower city on a small plain at the confluence of the rivers Kokcha and Amou Daria, historically known by its Latin name Oxus. Also secure on 20 meter-high river banks, the plain area provided a level platform for a sprawling civic, palace and residential complex. Planned on the grandest scale from the start – albeit not a hard rectangular Greek layout, the city is orientated around a bold central corridor running from the northern fortifications to the rivers.

Grand Propylaea (gateways), temples and the 5000 capacity mountain-side theatre line this processional route to the colossal Palace centre-piece. This vast Greek complex measuring some 350 by 250 metres was both the civic heart, treasury and ruler’s residence. The palace gateway was supported by 18 columns. Within, the palace’s own courtyard was lined with 118 elaborately carved Greek Corinthian columns some 5.7 meters high, others 10 meters high. The palace interior was a carefully planned sequence of rooms and halls arranged for segregation, security and privacy. To its south stood a vast open plaza of 27000 sqm, thought to be for military drill and public display. To the western side of the palace courtyard was the 21 room treasury, a vast storehouse for all things valuable, where the remains of storage jars labelled in Greek recorded all: gemstones, ivory, olive oil, incense, contracts, records and hundreds of coins – some gold, depicting the Seleucid kings as Alexander.

Walls were carved in the Greek architectural style and lavishly painted with frescoes, floors richly decorated with mosaic tiles. Around the palace, three temples were discovered and the land to the south overlooking the rivers was found to be the suburb of the aristocrats’ grand houses, some sporting Greek columns of over 8 meters high. And of course, there was a gymnasium complex. Being a true Greek centre, a library was essential too; parchment fragments of the works of tragedies and philosophy were recovered by the archaeologists. With every new artefact uncovered by the team, a new piece of Afghanistan’s ancient history became clearer.

But Ai-Khanoum is not just a triumphant display of all things Greek. Before its existence ultimately came to a sudden end around 145 B.C.E with the invasion of nomadic tribes from the northern Steppe, it was a city at the then heart of the world, enriched by trade with China and India and beyond. Archeologists found the site was awash with not only Greek, but Mesopotamian, Indian and Chinese artefacts; a treasure trove of ancient objects.

The excavation mission was inevitably halted with the outbreak of the Russian-Afghan conflict in 1978. Unrest in Afghanistan since the 70s has prevented further large scale investigation with the site having been relentlessly looted and control squabbled over by the warring factions.

Ai-Khanoum’s palace walls and foundations were gutted and used as a quarry. Decorative limestone capitals were destroyed in lime kilns and the US-backed Northern military alliance used the acropolis as a base for a gun battery, destabilising and causing untold damage to the monument.

Some artefacts were moved to France before the Soviets forced out the French archaeologists, but many others priceless objects that were kept in Afghanistan at the Kabul Museum or hidden in the Central Bank went missing. At the site of Ai-Khanoum, which has been irrevocably compromised, hundreds of holes were dug by looters who sold countless undocumented treasures on the open antiquities market or directly to private collectors (the Taliban are also notorious for using the antiquities trade to finance their cause).

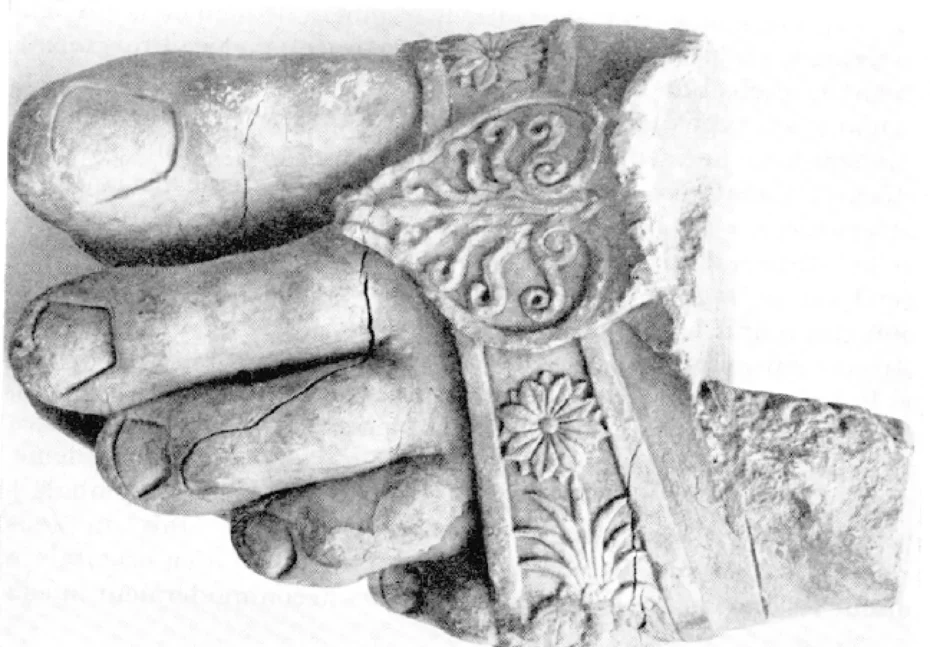

One of the most significant finds that was stolen from Ai-Khanoum amidst the seemingly endless conflict that has threatened Afghan antiquities in the last few decades, was a colossal marble left foot, once belonging to a statue of the Greek God Zeus, found in the main temple by the French team in 1968. Classicist author Llewelyn Morgan tracked the movements of this exquisitely detailed globetrotting foot which eventually turned up in Japan in 2001 and is now part of a perpetually travelling exhibition. “When in 1995 an inventory was taken of the Kabul Museum’s holdings, the foot was gone, along with many treasures from this remarkable institution,” writes Morgan. “From the mid-nineties until 2001 the trail went cold, but in April 2001 news reports surfaced announcing the presence of Zeus’ foot in Japan [and] would be put on display at the Ancient Orient Museum in Tokyo. The report claimed that the artefact, illegally removed from Afghanistan and put up for sale on the international art market, was bought by an anonymous benefactor in Tokyo”.

Afghanistan’s professional experts in archaeology, curators and historians unsurprisingly left to other countries after decades of civil war. Only time will tell if any future governing regimes will take an interest in rehabilitating, reconstructing, and improving the desperate condition of Afghanistan’s historical and cultural heritage.

At the crossroads of Eastern and Western ancient civilisations, Afghanistan very likely still holds the key to a vast amount of untold history in hundreds of unearthed archaeological sites dating as far back as the Stone Age. Bactria, the Afghan region where the ruins of Ai-Khanoum were found, was once known as the land of a thousand golden cities, an enclave of the largest and richest cities of antiquity. The most spectacular of them is widely believed to have been Ai-Khanoum, the remains of which are still a vivid testimony of Greek civilisation in Afghanistan, a culture which started with Alexander the Great and became firmly established through the later Greco-Bactrian Kingdoms. Alexander the Great would become the defining inspiration for Ancient Rome’s later expansion in military and cultural conquests. Rome, though, looked westward and never sought nor found those far-eastern pavilions of what was so glittering, but is for now, once again lost in the sands of Afghanistan.