It’s the first decade of the twentieth century, and you’re in London reading the avant-garde weekly magazine, The New Age. A writer you’ve been enjoying, a women’s suffrage advocate named Beatrice Tina has been arguing, via the “Letters to the Editor” section, with someone called D. Triformis. But recently, they’ve managed to find some common ground. Beatrice Tina is so grateful, she lets Triformis in on a little secret: she is not really Beatrice Tina. In fact, she’s Beatrice Hastings, the militant suffragette and unconventional feminist whose notorious book was recently boycotted. What’s left unsaid, of course, is that Triformis has a secret too: D. Triformis is also a pseudonym … for Beatrice Hastings. And on that note, let’s get some clarity on just who this mysterious chameleon, who wrote under at least thirteen different pseudonyms, actually was. Avant-garde feminist? Parisian war correspondent? Occultist? Forgotten Modernist? Modigliani’s first great love and muse? As it happens, she was all of the above.

“In literary and art history scholarship, Hastings rarely appears other than as an occasional footnote to the life stories of her more famous contemporaries,” writes University of Birmingham’s Dr. Chis Mourant in his essay about Beatrice’s time in Paris.

Beatrice Hastings was born Emily Alice Haigh in South Africa in 1879, but would change her name upon moving to London as a young woman, along with reinventing nearly everything about herself several times over through the course of her life. In addition to being Modigliani’s first “great love” and model, she was a journalist, a novelist, a poet, a political advocate, a convert to Theosophy, a spiritualist religion and philosophical school established during the late 19th century that had a profound and long-lasting influence on modern, and particularly abstract art. In short, she was what she would be later described as, a woman with “as many faces as voices.”

Hastings wrote and co-edited for the socialist journal The New Age under or a long list of pseudonyms, including the battling “Beatrice Tina” and “D. Triformis.” Some researchers believes she may have done this merely to help the magazine look like it had a larger staff than it did. Her contributions (political essays, parodies, poems and fiction) overwhelmingly addressed women’s suffrage and “she was unafraid to address issues such as sexuality and infidelity”, notes the Modernist Short Story Project. She went head to head with major figures in the early Modernist poetry and may have launched the career of Ezra Pound while simultaneously publishing parodies of him. Her creative freedom at the magazine was highly unusual for a woman of her time and such liberties may have been in part due to her relationship with its publisher, A. R. Orage. Hastings and Orage were romantically involved, with both of them also enamoured with the writer Katherine Mansfield, who was one of Hastings’ closest friends as well as a romantic partner. As members of London’s Theosophical Society, the trio were also defenders of the movement and its founder, notorious seance queen Madam Blavatsky (later exposed as am imposter).

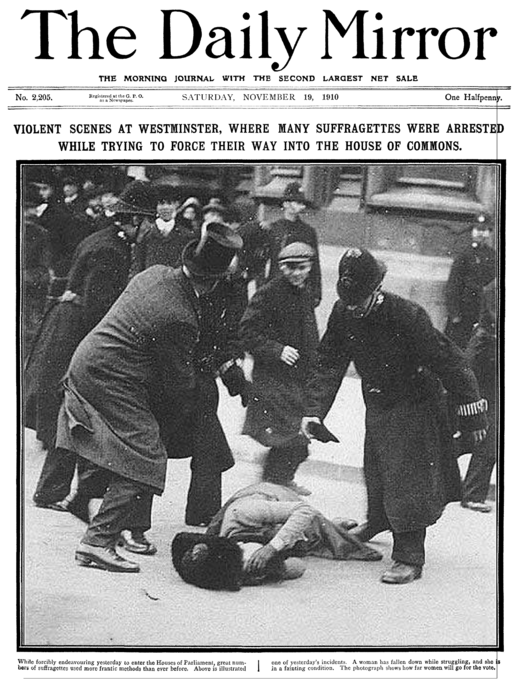

And when they weren’t involved in spiritualism, they were staunch supporters of the suffragettes. When Hastings convinced Orage to join her suffrage rally with the Pankhursts, he became the second man ever arrested for participating in a suffrage demonstration.

Hastings’ feminism was not just militant however, it could be playful, funny, and personal. Her published novel, “The Maids’ Comedy,” is a feminist parody of Don Quixote set in South Africa, her country of origin. She also, with Orage’s paper assisting, managed to drum up a feud with the children’s writer E. Nesbit over birth control, which Hastings passionately supported.

Unfortunately, the relationship between the Hastings, Orage and Mansfield couldn’t last, and when it eventually collapsed, a devastated Hastings did the most obvious thing she could think of: write and publish a book of gossip about Mansfield, Orage, and all their friends under a thin veneer of “literary history” entitled Old New Age, and flee to Paris.

In Paris, she continued to write for The New Age with a regular column called Impressions de Paris, under a new pseudonym, “Alice Morning”, chronicling her life as she settled into Parisian café society in Montparnasse and offering readers a window into the Belle Epoque world where Europe’s writers and artists were congregating.

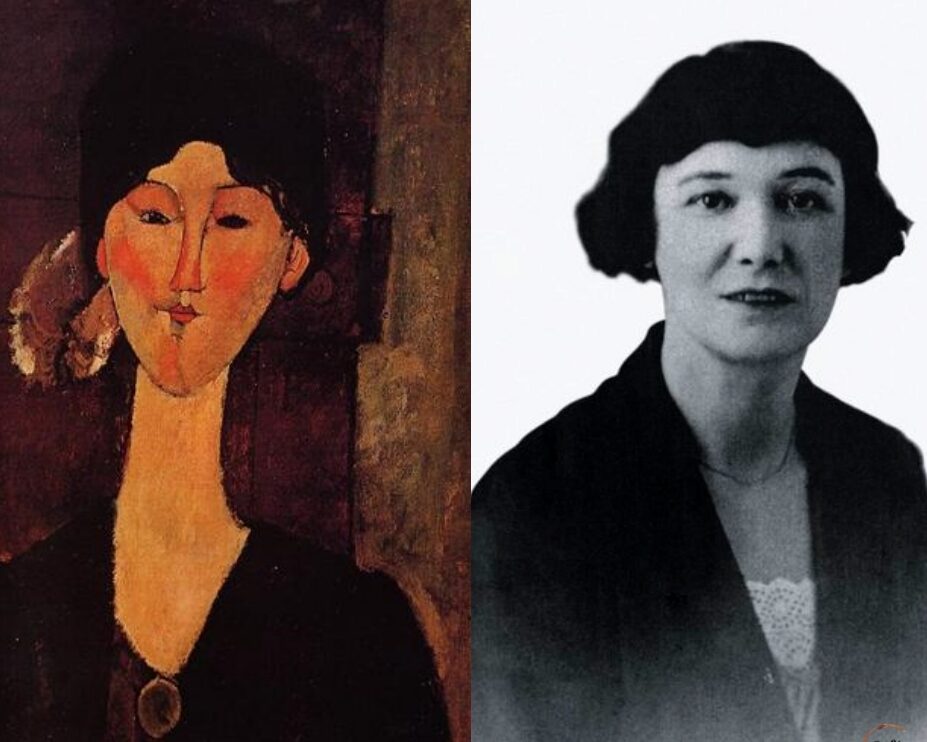

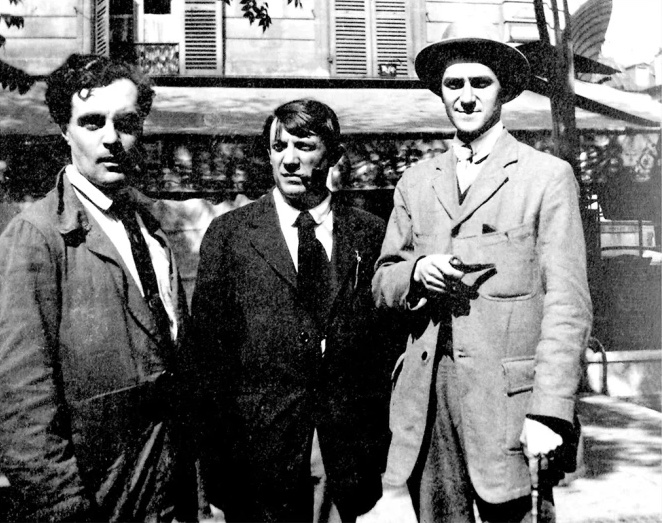

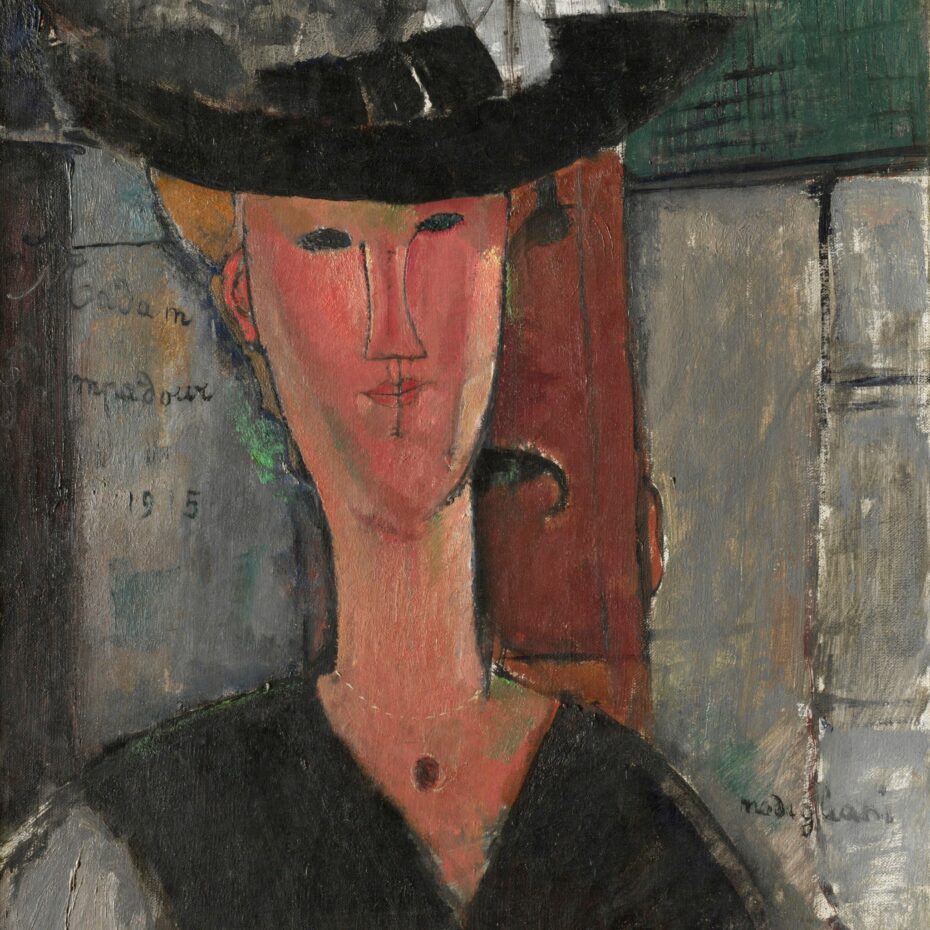

Among them was a young Amedeo Modigliani, who she initially found “ugly, ferocious and greedy”. She warmed to him quickly enough though, and the two of them fell in love and moved in together soon after. For Modigliani, who was younger than Hastings, this was his first serious relationship, and their two passionate and tempestuous years together inspired him through a period of creative productivity, resulting in multiple portraits of Beatrice herself, giving her as many faces and likenesses as she had pseudonyms.

Beatrice too, flourished during her time with Modigliani, writing war correspondence from a Paris under siege during World War One, as well as a novella based on her relationship with the painter, which she wrote under the name “Minnie Pinnikin.” Writing as “Alice Morning,” the Modernist Archive points out that “she even published what may be the first piece to self-designate as “modernist” —a short piece entitled “Modernism” in 1912.” The period in literary history we now call the Modernism Movement counts T.S. Eliot, Franz Kafka, Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, Joseph Conrad and W.B. Yeats as the key writers that rebelled against clear-cut storytelling and formulaic verse from the 19th century. Hastings’ name however, has rarely been mentioned among them.

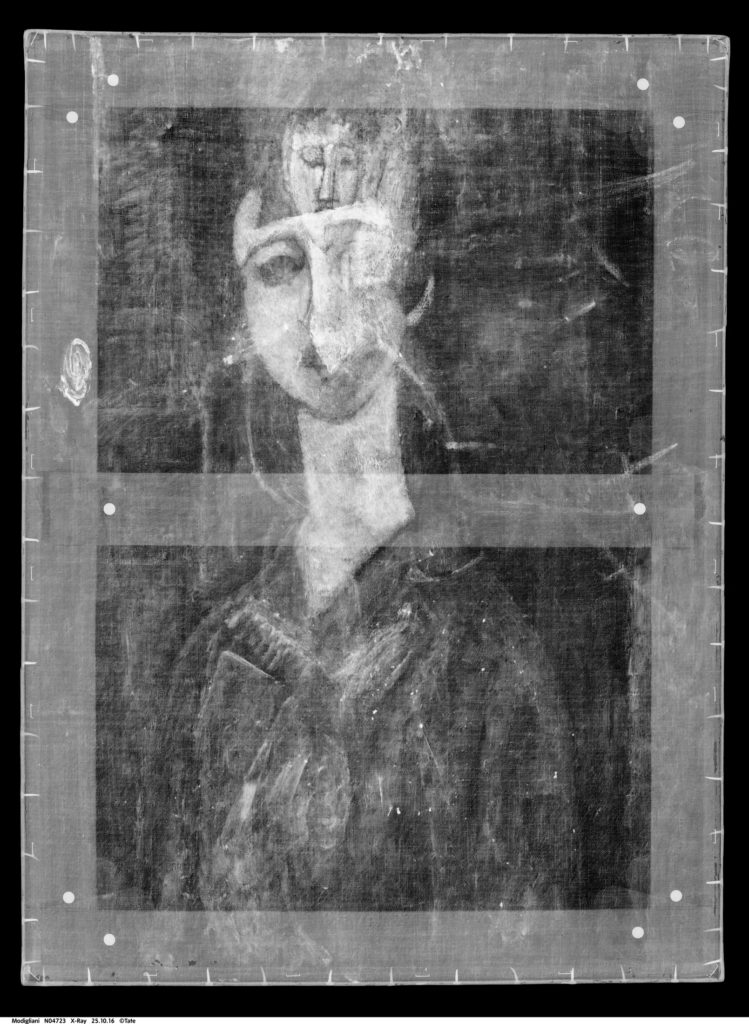

The end of the romance between Hastings and Modigliani broke both of their hearts. Hastings would return to London; Modigliani, hoping to avoid any memory of Hastings, would paint over his last portrait of her.

Both their lives would take sad turns after they parted. Modigliani’s demise is of course better – and more kindly– documented by history. Biographers in the past have frequently dismissed her has a woman “suffered from delusions of literary grandeur” (Peter Washington), while biographer Jeffrey Meyers labelled Beatrice as a wild “sexual juggernaut, physically aggressive and determined to take her pleasure in the same way as a man”. Both she and Modi died destitute; both had stormy relationships outside the ones they had with each other. For Hastings, who could perhaps never quite decide who she wanted to be, her death marked the death of at least 13 different personas. Even now, no one is sure that all of her pseudonyms have been uncovered.

That portrait of her that Modigliani painted over, became Portrait of a Girl, a 1917 masterpiece, currently owned by the Tate. It was recreated over a century later, when scientists from a company called Oxia Palus used x-rays, AI, and a 3D printer to bring Hastings back into the eye of the world as part of a collective effort by more recent scholarship to reposition her at the epicenter of English and French modernist culture.

“She has frequently been characterised merely as the ‘fiery mistress’ to various male protagonists of modernism,” writes Dr. Chis Mourant. A woman hidden in the aftermath of a failed romance, who was uncovered and shown as a modern wonder, who people would marvel to behold, it’s not hard to think that Beatrice Hastings (and her many selves) would have enjoyed that.