Legendary pin-up Lana Turner is said to have been discovered perched on a bar stool bound in a tight sweater at the famous Schwab’s Drugstore on LA’s Sunset Strip. The Drugstore was the quintessential, aspirational, all-American immersion, where the cool kids hung out, fell in and out of love, plotted and gossiped behind the soda fountain. It was an essential piece of Americana which sooner or later had to follow the movies, the music and the rest of the post-war American culture overseas to Paris and become the cool crowd’s HQ of 1960s Europe.

The Drugstore’s passage across the Atlantic came about when French advertising magnet Marcel Bleustein-Blanchet was totally seduced by the insatiable, eternal 24/7 heartbeat of Manhattan during a stint as a young advertising executive on Madison Avenue in 1949.

“At midnight, I found myself in the street without having eaten dinner, lost. I saw the light of a small shop (a drugstore). I went in to ask for directions. In two minutes, I was able to buy a hamburger, a toothbrush, a newspaper and a pack of cigarettes. To get the same thing in Paris, I would have had to find a tobacconist, go into a café and give up the toothbrush, for lack of an open pharmacy…”

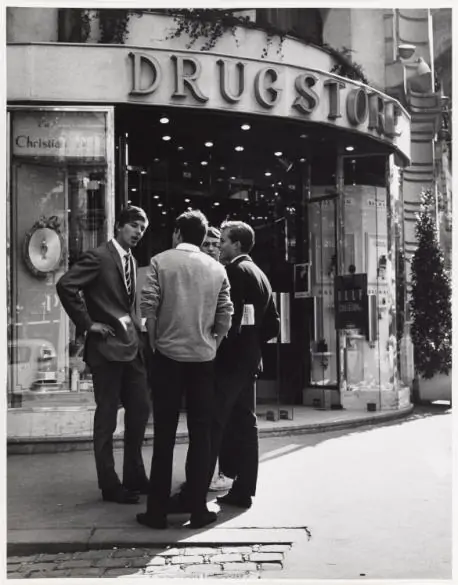

He wanted to capture that Edward Hopper ‘Nighthawks’ moment and export it straight to the centre of Paris – the top of the Champs Elysées specifically, where he moved his new agency into the upper levels of a building overlooking the Arc de Triomphe in 1958 and exploited the entire ground level for his new sprawling Drugstore Publicis. This vast, bazaar-like complex mimicked the one-stop music, food & drinks bar culture, convenience shopping and social hotspot Manhattan had so indelibly imprinted in his mind ten years previously. Suddenly, the citizens of Paris were gorging hot dogs and eggs easy over and sipping on drinks from a soda fountain. There was also a pharmacy squeezed amongst the shoe-shiner, popcorn maker, bookshop and gift shop. This was not traditional French bistro that Parisians had called their HQ for generations; this was a revolution to the old social patterns and pretty soon the word “drugstore” would be seen in big type across the city.

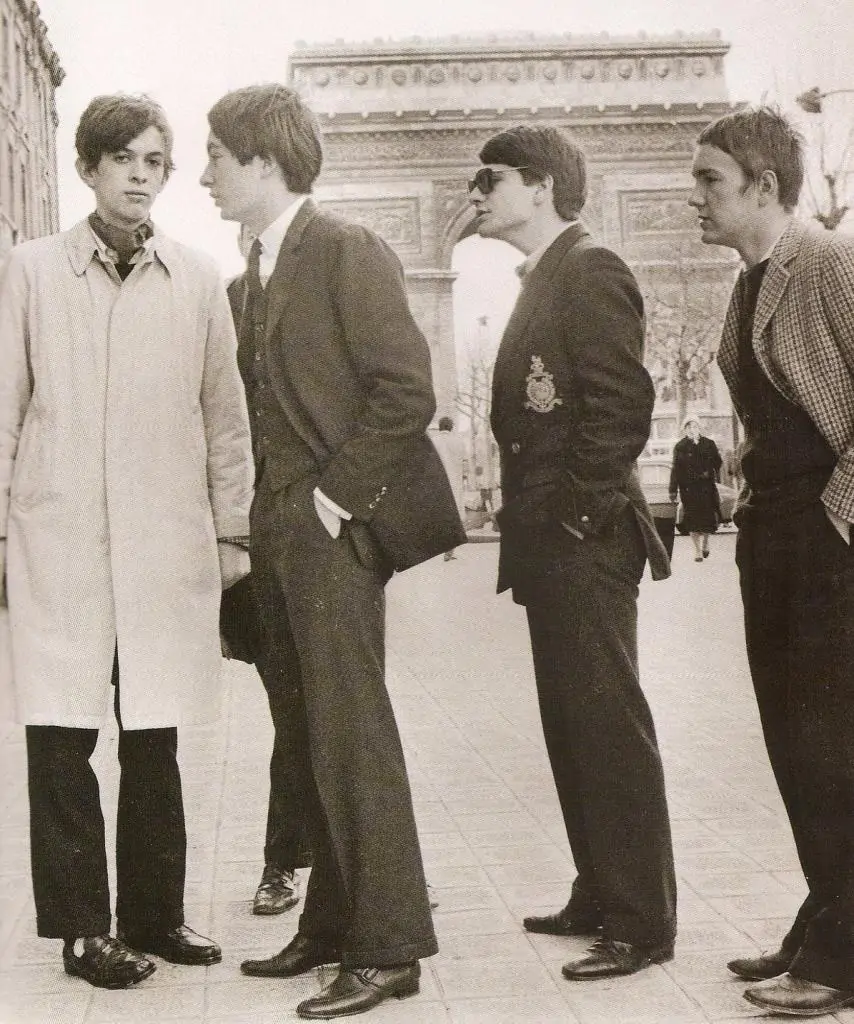

Packs of teenagers and pretty young things would descend on Le Drugstore as soon as school bells rang. This cosy, suave, all-American setting became their place to see and be seen. By 1961 the obligatory milkshake or hamburger was currency for a perfectly poised seat to ogle, observe, flirt, seduce – and have spectacular fights, should the occasion arise. These kids who hung out at Le Drugstore were called ‘minets’ as they supposedly hated everything French and coveted only English language culture. The fashion output was part of the seduction of Le Drugstore, and its sophisticated teenage fashionistas sported a style that was distinctive; think Twin Peaks mixed with English country set, with close-cut tweed, brightly coloured corduroy trousers, plaid skirts and hounds tooth pea coats – somewhat preppy (but definitely not new preppy) and just a tad shabby for that French nonchalance.

French yéyé singer and hearthrob, Jacques Dutronc, was perhaps the archetype of the Parisian Minets, and even sang about them in his songs. “J’ai pas peur des petits minets qui mangent leur ronron au Drugstore”.

Le Drugstore was thriving on the Champs-Élysées, and expansion followed in 1965. The second Le Drugstore landed in the heart of historic Saint-Germain, opposite Parisian institutions of the Belle Epoque, Les Deux Magots and Café de Flore. Five thousand guests celebrated this piece of all-encompassing modern interior architecture of shiny glass, chrome, brass and wood designed by the multi-talented Wiatscheslav Vassiliev who worked many of Marcel Bleustein-Blanchet’s Drugstore projects.

Many copycat venues opened all over Paris with American-sounding names including the word “drugstore. By 1970 there were a whopping 50 American-style Le Drugstore-type venues in Paris, testament to just how successful this American recipe was. The cult and commercialism of the American drugstore was infiltrating Europe and similar mini-malls opened, from London (The Chelsea Drugstore) to Barcelona (El Drugstore). Like the Eiffel Tower, by the 1970s, the original Le Drugstore had become part of the Parisian tourist experience. Air Canada advertised:

‘If you want to go to Paris, have breakfast at Le Drugstore, lunch at Maxim’s and head right back home again … Air Canada won’t stop you. Your diet might though.’

Back in London, an extract from an unedited article from The Times’ print archive (1970) reads,

“True to its boast that it has just about everything— except drugs, that is—Le Drugstore opened here Monday. Like its 50 European counterparts, it sells clothes, gifts, books, tobacco and delicatessen food. In addition, it houses three restaurants and a bar. When the first Le Drugstore opened on the Champs Elysee in Paris 11 years Ago, it was said to be based on the American idea or a drugstore: a mini‐department store that dispensed’ food as wen as prescriptions and sold anything it had room for. Parisians adored it, do drugstores sprouted all over” the city, including one with a movie theater in it”.

But disaster struck when a massive fire, deemed to be arson, killed one person and injured many in September 1972 at the original Champs-Élysées Drugstore. Architect Pierre Dufau replaced the entire building with a 6 floor contemporary glass box, the ground floor entirely dedicated to the Drugstore again.

Further mayhem ensued in 1974 when the sister venue, the Saint-Germain-des-Pres Le Drugstore was damaged by a grenade thrown by a revolutionary terrorist from its mezzanine level to the crowded shopping floor below, killing two shoppers and injuring 30.

The 80s saw decline, but the Drugstores had now become a distinctive aspect of French culture. Parisians strongly objected to the closure of the Boulevard Saint-Germain location when it was transformed into an Emporio Armani store in 1995. However, you can still visit, shop, browse magazines, maybe even spot a retired former “minet” sipping cola at the bar of Le Drugstore on the original Champs Elysées. Redesigned by Tom Dixon in 2017, with a “nod to the glamour and sophistication of the 1960’s world of advertising”, it’s not exactly the place where you’ll find French teenagers puffing away on cigarettes to the tune of the 1960s optimistic Anglo/American soundtrack, but it’s still part of Parisian history.