Curiously absent from our historical timelines is “The Great Binge”, a more recently-coined but arguably more appropriate term for that famous period at the turn of the century which we typically refer to as the “Belle Epoque” or the “Gilded Age”. This wasn’t just a time when culture and industry flourished however, it was also a boom era for narcotics, when the wealthiest businessmen in the world were also drug smugglers, literary heroes were openly depicted as heroine addicts and everyday remedies containing cocaine, laudanum or heroine resulted in shocking infant mortality rates. If it’s a more accurate picture of the past we seek, we can start by peeling back history’s glittery filter of any so-called “golden age”.

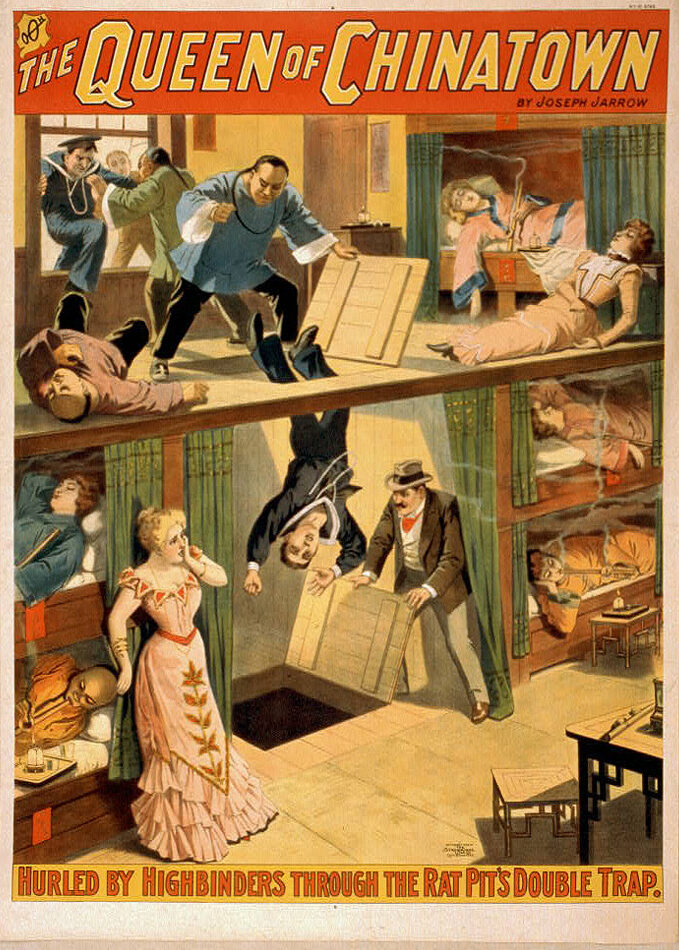

Sherlock Holmes: a better name than any to embody this strange time in history where almost everyone was quite literally on drugs. On any given page of Arthur Conan Doyle’s iconic books you can find his misanthropic hero openly deciding whether his drug du jour should be heroin or cocaine. Or beyond fiction, there was John Jacob Astor, America’s first multi-millionaire and a titan of industry who made his fortune from the fur trade and investing in New York real estate, but also by smuggling Ottoman-produced opium into China, and later becoming Britain’s most important opium dealer.

The Great Binge refers to the period spanning 1870 to 1914 in Europe and North America. It was coined by modern historian Gradus Protus van der Belt to describe a time when drugs like cocaine, heroin, opium, absinthe, laudanum, and many more were freely available not just from your local pharmacy, tobaconists or the neighbourhood bar, but also from the barbershop, the stationers, and even confectioners.

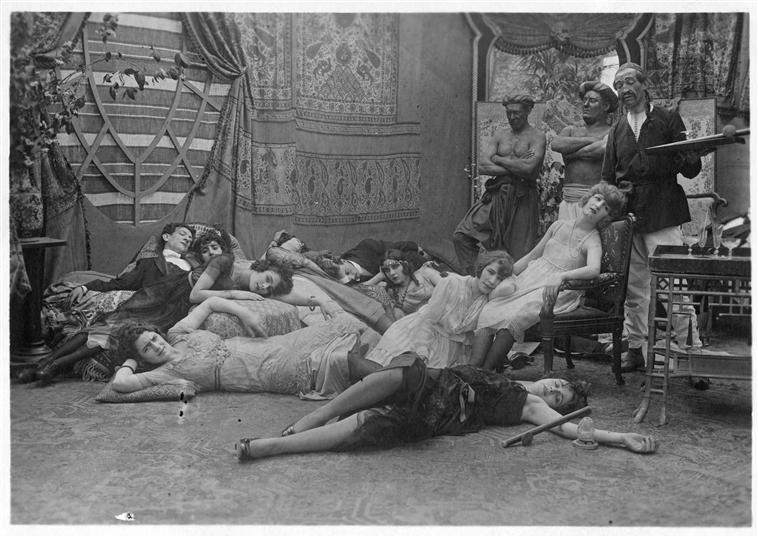

The impact of colonialism was perhaps the main component for the flourishing (and legal) drug trade, with companies like the British East India Company and the British Levant Company supplying large quantities of opium around the globe in the 18th and 19th centuries. Between 1827 and 1842, over 27,000 pounds of opium came into the ports of the United States alone, where the drug found an unexpected distribution network of businessmen, presidential parents, and even Ivy League schools, which all had ties to the Opium trade in the late 19th century.

“Princeton’s first large benefactor, John Green, funded his contribution through the opium trade […] Yale University’s infamous Skull and Bone society was funded by the Russels, the most successful family of opium dealers in America,” reveals Harvard’s magazine, The Crimson, adding that as America’s gateway institution for the drug that soon spread to other Ivy Leagues along the East Coast, “Opium once pervaded campus life at Harvard […] throughout the 1800s, its black smoke kept the university’s veins flowing with green and its faculty and students perpetually dazed.”

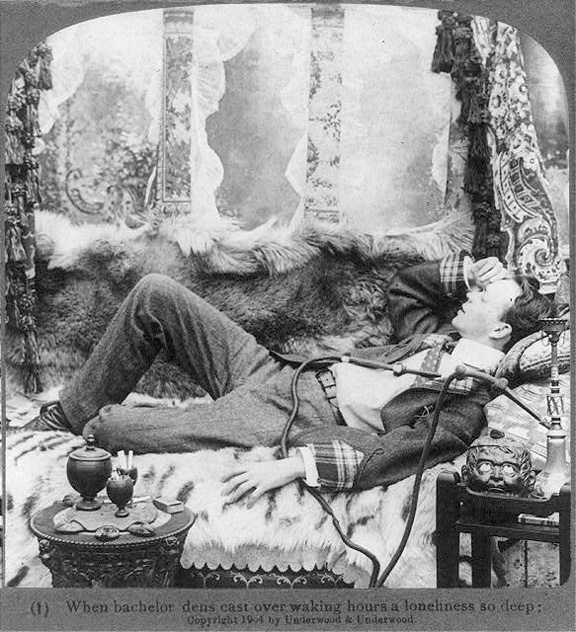

The term “pipe dream” actually originates from the opium dens of turn of the century America where people smoking an opium pipe would come up with ideas, theories and fantasies whilst hallucinating.

But opium, particularly its derivative laudanum (a tincture of opium mixed with alcohol), wasn’t just used for recreational purposes. It was the go-to medication for all kinds of ailments, from headaches to diarrhoea or even mild treatments like hiccups. People kept laudanum around the house, ready to use for everything, from headaches and insomnia to diarrhoea, the way most people have a box of paracetamol around the house.

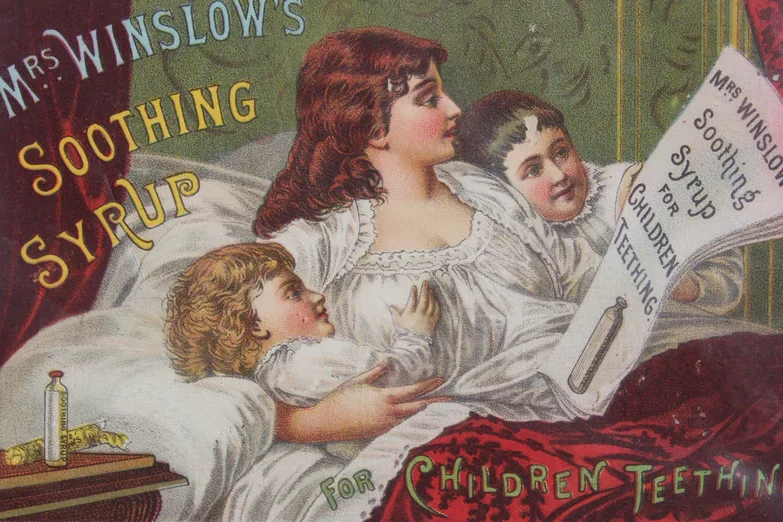

And tragically, consumption wasn’t limited to adults; everyone was given opium, regardless of age. In 1854, it was recorded that a devastating 75% of drug overdoses occurred in children under the age of 5. If you had a teething baby, during the Great Binge, you’d likely have been prescribed a widely marketed cough medicine called Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup which contained high doses of morphine and claimed that it could “sooth any human or animal” – including a restless infant. The product was not withdrawn from sale until 1930.

When German chemists synthesised diacetylmorphine from morphine in 1895, the German pharmaceutical company Bayer – known better today for its Aspirin – introduced heroin as an innovative pain reliever and cough suppressant. Their ads offered: “Aspirin for joint pains. Heroin for coughs”, the latter of which was touted as a “non-addictive” alternative to morphine. Like with other opiates, it treated various conditions, from toothaches to depression, and was even used as a treatment for shyness in children.

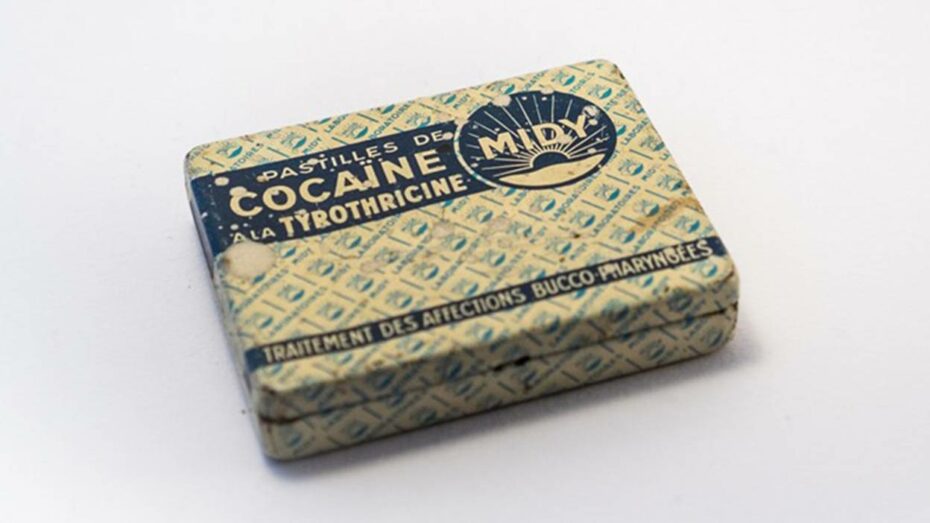

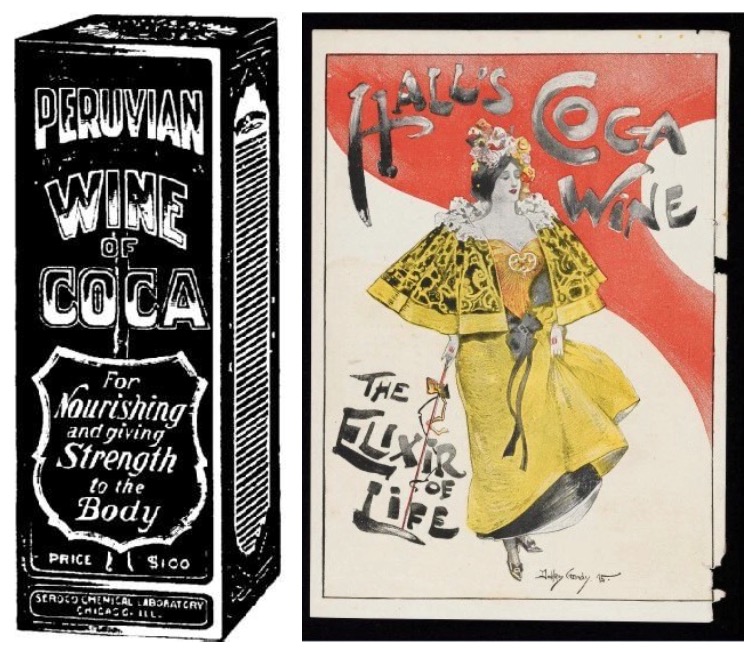

Brewed and chewed in Andes for thousands of years (in its natural coca leaf form) cocaine came to the pharma party in the 1860s when another German chemist, Albert Nieman, isolate. Within 20 years, doctors would be using it as an anaesthetic effect during eye or throat surgery, but like its buddy heroin, it was also marketed as a cure-all; from haemorrhoids to indigestion and appetite suppression to fatigue. Cocaine was so widespread that some medications, like seasickness pills, stated they did not contain cocaine.

Soldiers were sent off to the Great War carrying first aid kits packed with cocaine and morphine. They were even sold as “useful presents for friends at the front.” The father of psychoanalysis himself, Sigmund Freud, was a notorious cocaine user in his younger days, as he went through a phase experimenting with the drug and recommended it as a form of therapy for depression and alcoholism. Dominic Streatfeild, the author of Cocaine: An Unauthorised Biography, said that “If there is one person who can be held responsible for the emergence of cocaine as a recreational pharmaceutical, it was Freud”.

Coca would also get an endorsement from an unlikely place: Vatican City. During the Great Binge, one notable drink in circulation was the Vin Mariani, an alcoholic beverage that combined both wine and cocaine and received endorsements from not one, but two popes. The popular concoction contained about 6 milligrams of cocaine per ounce, and Pope Leo XIII even allowed his face to be used in Vin Mariani’s marketing campaign. He was very much a brand ambassador, citing that it strengthened him “when prayer was insufficient”. The Papal endorsement led it to become many a religious leader’s drink of choice. In the secular world, the Belle Epoque’s most famous names, Sarah Bernhardt, Jules Verne and even Queen Victoria were all fans of the drug-infused cocktail that would spend the following century cleaning up its act to become the world’s most iconic household brand: Coca Cola (more on that here).

Another alcoholic drink of choice during the Great Binge was of course the highly hallucinogenic, absinthe, which had quite the PR campaign that earned the popular potion its famous nickname, “The Green Fairy”. When a plague of pests destroyed vines across Europe, striking France with The Great French Wine Blight in the 1850s to 1870s, absinthe become the drink of choice (and the breakfast of champions) for artists, poets, and bohemians of the Belle Epoque.

The wine scarcity pushed the prices up and the working classes also turned to the new alcohol distilled with wormwood and flavoured with anise. There has been much debate over the hallucinogenic properties of absinthe. It was banned in France for some time due to its alleged effects of causing hallucinations, psychosis, and strange, dangerous behaviour, but modern science chalks up the trippy effect of the Green Fairy more likely due to its high (higher than whisky) alcohol content that was being consumed without moderation by the general population from morning to night. Most symptoms, like hallucinations and psychosis, were in fact due to chronic, heavy alcohol use.

Although the absinthe ban happened in Switzerland in 1905, with other countries following suit, the irony is even though absinthe is not actually a “drug” any more than alcohol is (and the ban was lifted in the EU in 1998), it took a while for harder drugs to get the same treatment.

In 1908, President Roosevelt appointed Hamilton Wright as the first Opium Commissioner in the United States to begin targeting opium dealers. The irony here is that Franklin D. Roosevelt’s grandfather, Warren Delano, was an opium peddler, and his drug trade was responsible for the bulk of the family’s fortune. Roosevelt’s mother, Sara Delano, travelled to Hong Kong with her family to join her opium-trading father in the 1860s.

The crackdown on the Great Binge inevitably began with the signing of the 1912 International Opium Convention to suppress opium smoking and to limit it to medicinal purposes. In the 1920s, in the US, an anti-drug crusade also saw heroin cough drops and cocaine tablets to slowly disappear from stores and bathroom cabinets. Picking up hard drugs from a local store or pharmacy were ultimately criminalised too of course – or were they? In the midst of an opioid crisis and fentanyl epidemic in the US, one has to wonder if we ever really recovered from the Great Binge.