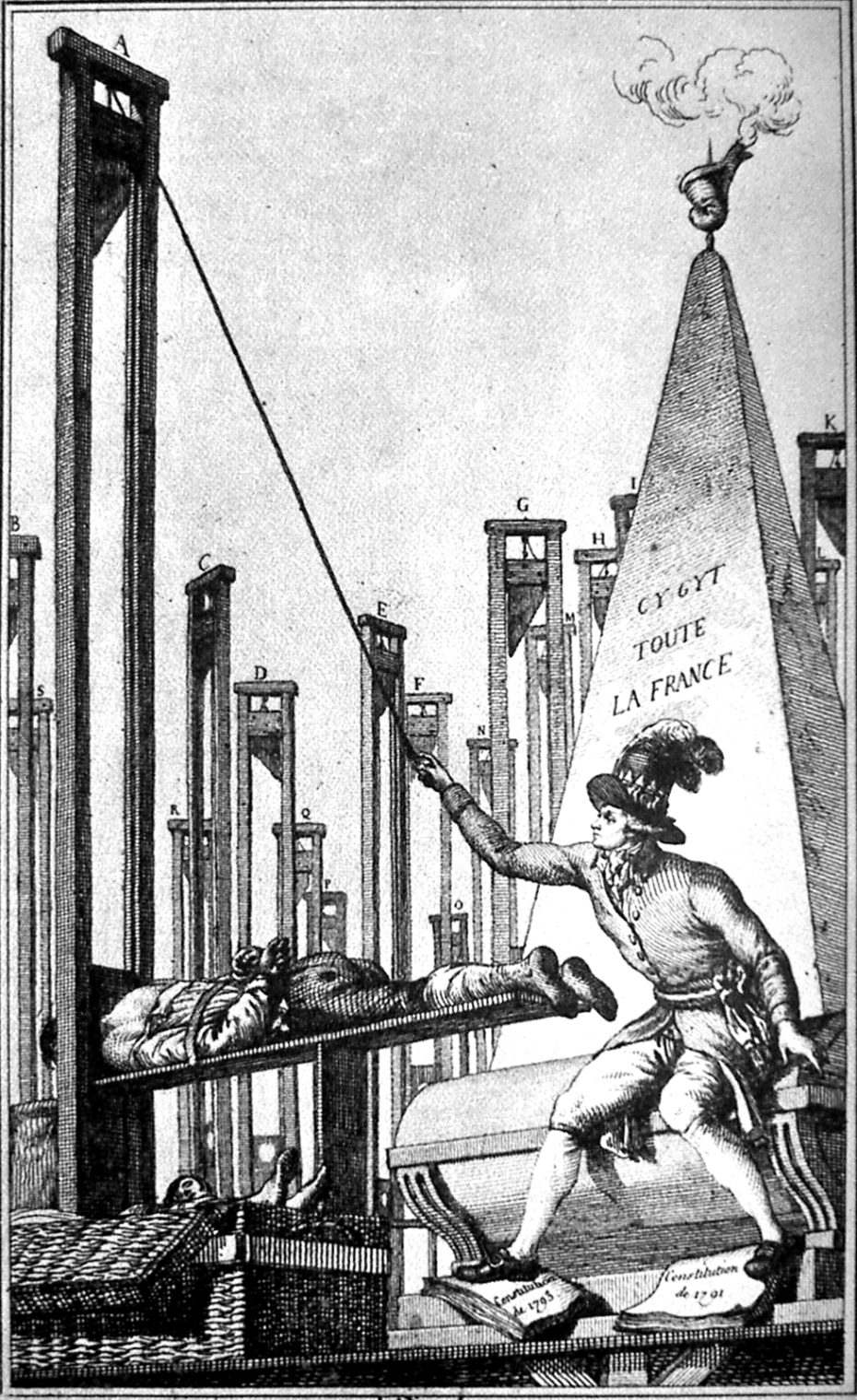

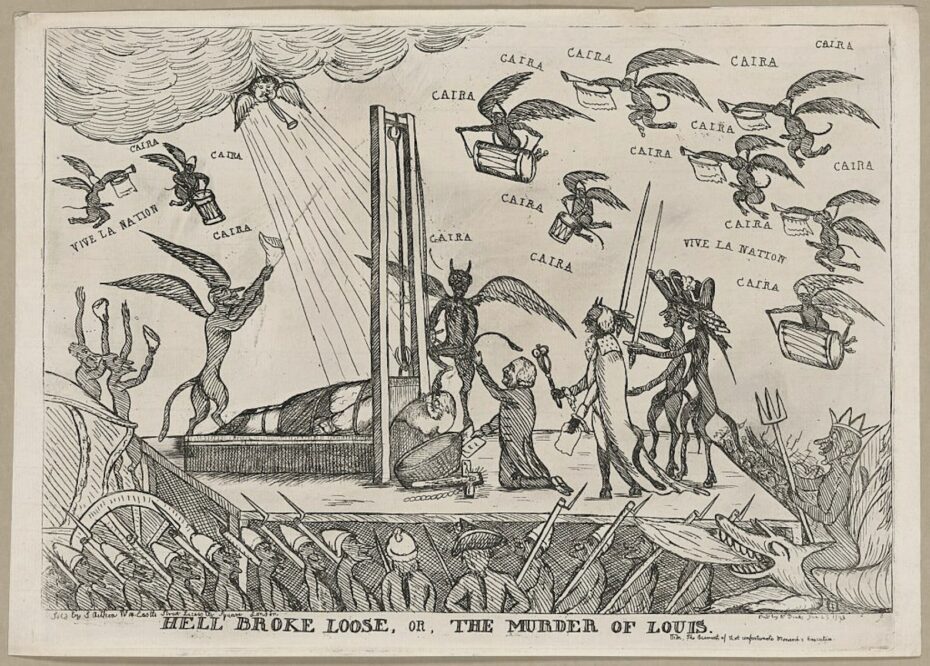

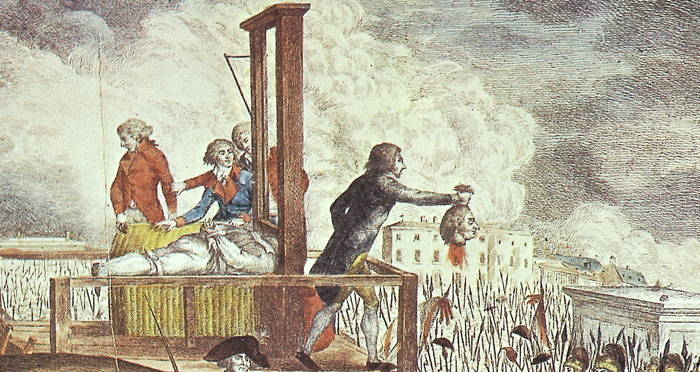

In Paris, when his father died in 1644, Louis Desmorest inherited his family’s execution business at the age of 10. His mother had been part of an established execution family that had been in business for the past 100 years. Desmorest’s mother’s clan also hatched the most notable of all the execution families, the Sansons, who dealt in death for six generations, starting with Charles Sanson, who founded their dynasty in 1688, operating before, during and after the French Revolution, spawning over 200 executioners. The career highs for his descendant, Charles-Henri Sanson, were the first use of the guillotine in Paris and the execution of Louis XVI in January 1793. He was titled by the citizens Monsieur de Paris (the Gentleman of Paris), and his second son Henri, executed Marie Antoinette in 1793.

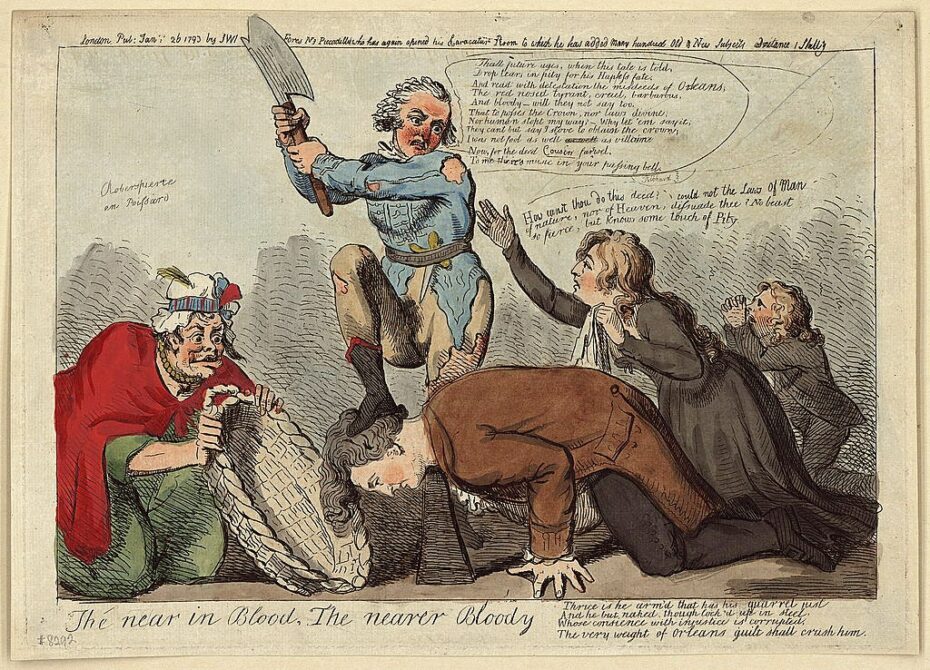

Public execution has long been both the expression of authority and a morbid muse for the masses. All cultures and societies seem to have engaged in the death ritual at one point in time; for spiritual appeasement of the gods in the case of the Aztecs, for keeping society in check as the Romans did so mercilessly, or as so famously put into practice by French revolutionaries, to overthrow the monarchy itself. Images of hooded goblin-like operatives applying a regime’s ruthless with a variety of deadly tools – nooses, swords, axes and of course, guillotines – have endured in our historical consciousness. But rarely do we imagine public execution as … a family business.

In Germany, a Franz Schmidt inherited the business of executioner from his father in the Bavarian town of Hof in 1573, his final test was the beheading of a stray dog in his father’s back garden. He would later become the Chief Executioner in Nurnberg after marrying the then Chief Executioner’s daughter. He was famously illustrated at the time decapitating Hans Froschel by swinging a very large sword to the neck. Franz left a rich and intimate diary, recording not just technical detail, but considered opinion itemising his 361 career executions. Franz formally retired from the execution business to continue as a very successful medical practitioner, later dying a respectable rich man.

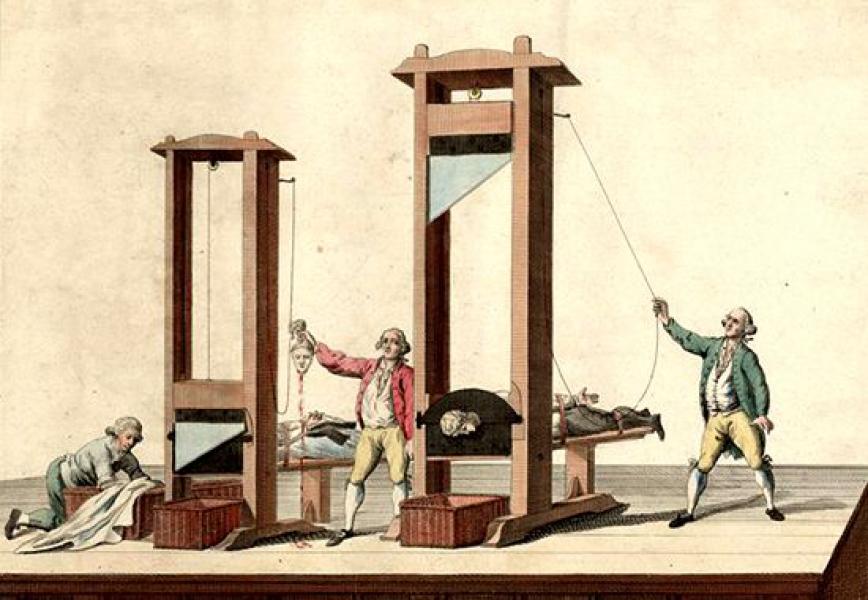

The quantity of work required by the French Revolution put extreme pressure on the executioner. In a trade reliant on skilled rope and blade work, those new to the trade had a lengthy and steep learning curve, but protocol and procedure was everything, no ragged cuts please! To relieve the situation, the guillotine was employed. The guillotine was quick, reliable, clean and impersonal, perfect for industrialisation of deadly justice. This higher capacity device was not only for the benefit of those to be executed, but supplied the growing medical professionals’ need for fresh, well … almost intact bodies. Protocol still had to be followed, there was to be no post-beheading degradation or humiliation of corpses or their dismembered parts.

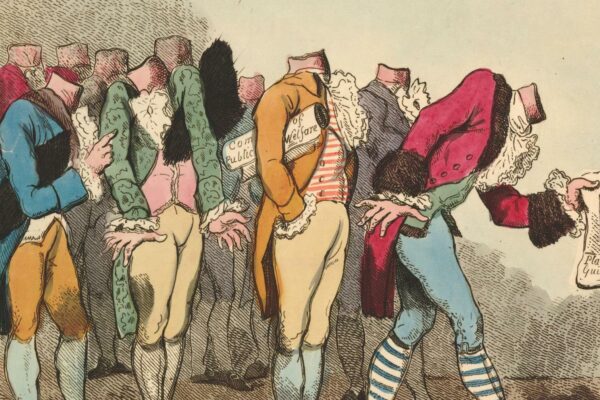

Both reviled and feared, the taint of marrying into the bloodline of death dealers was a death sentence in social society itself; according to Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History podcast, the general public had a superstition that executioners were untouchable. An interaction, befriending or being in a relationship with an executioner who had dispatched a relative was unthinkable, and they were kept well apart from society – certainly the executioner was never anybody’s friend and definitely not the most desirable of neighbours. An insult of the day was to be accused of dining with the executioner. Taking the job was an instant divorce from society for families and their heirs to come. The families had no choice but to intermarry (inevitably interbreeding); daughters to established executioners, first sons to inherit the business and second sons becoming assistants to the next city’s executioner. They became dynasties apart, only meeting among themselves.

Whilst in smaller European cities such as Edinburgh, although well paid, the job was inevitably taken up by the strange, aloof and often criminal individual (condemned themselves with some clemency agreement), very likely due to the lack of candidates. Indeed, in a complete role reversal, executioners became so specialised in their knowledge of anatomy they were often consulted as surgeons and medical professionals.

Execution seems never to have been an easy trade. Throughout the centuries, the job description not only required the ceremonial removal of heads, but the application of public beatings, pre-death tortures, as well as a light medical knowledge to facilitate disembowelling, quartering, and of course ropework skills for hangings. Burning and drowning were also part of the services required depending on local practices. The skilled application of hand-sharpened of swords and axes was essential too. An elegant and quick dispatch by the blade was expected for the high born. Some authorities would only allow 3 strikes, though poor technique or mistakes were regular occurrences. The daily routine also included detective work, sniffing around and infiltration of the dark corners of society, investigation and accusation, effectively creating their own workload. As populations grew across Europe so did serious crime, driving an ever-increasing need for executioners.

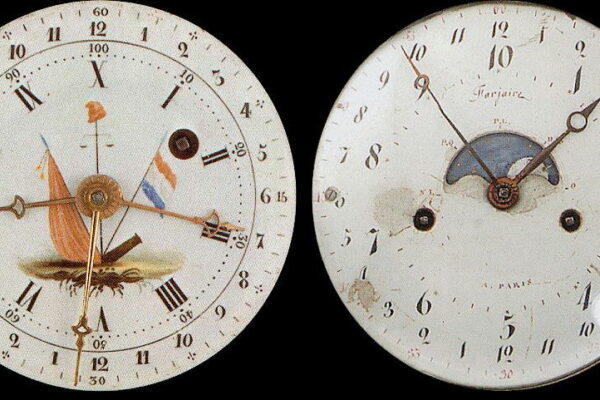

The public records from France list and identify the thousands of executioners who served the cities and towns from the 15th century onwards. Executioners were paid by the state in cash for a particular piece of work, but on a daily basis in kind from the public. In France, the “droit de havage “was the executioner’s right to collect food and goods from the cities’ traders. The executioners would be identified by offering a distinctive goods bag, as it was not acceptable for vendors or public to engage or touch them.

Edinburgh had used a guillotine since the mid 16th century up to 1710, and the accounts for its construction still survive, the wood frame, the blade, the weights and the names of those tradesmen who built it are recorded in the city accounts. So was a bizarre piece of local justice: should you be due for execution for stealing the lord’s horse, the horse would be tethered to a pin restraining the guillotine blade, upon which the horse would be bolted, releasing the pin – the horse your executioner.

Henri Sanson published his ‘Memoirs of the Sansons’ in 1830 and followed up with a supplement in 1862, that recorded the 159 years of the family’s Paris execution business to its last practitioner, Henri Clément in 1847. In 1939, public execution was finally banned in France following a public outcry when the botched and bloody guillotining of a Eugen Weidmann had been caught on film.

Charles-Henri had given up his studies in medicine in order to support his family as an executioner or bourreau, whose eventual execution record tallied almost 3000 souls. He was twice married and by his second marriage had two sons. The eldest, Gabriel who worked with him, unfortunately fell to his death from the execution platform in 1792, attempting the display of a severed head.

It all makes going to work in the morning that little bit easier to swallow, now doesn’t it?

Words by Cécile Paul