When did witchcraft actually become “cool”? At the beginning of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, three witches chanting “Double, double toil and trouble; Fire burn and cauldron bubble, something wicked this way comes”, were described as ‘old bearded hags’ by the playwright. Persecuted and hunted by the church for centuries but now popularised in modern culture, the hashtag “WitchTok” has seen millions of people flock to ‘witchy’ content creators and online occultists casting spells, brewing potions and attempting to evoke spirits. If there was ever an era to fearlessly identify as a witch and get hexing, this is it. But exactly how did it go from something that would get you burnt at the stake to à la mode? And who are the vanguards of this neo-pagan revival?

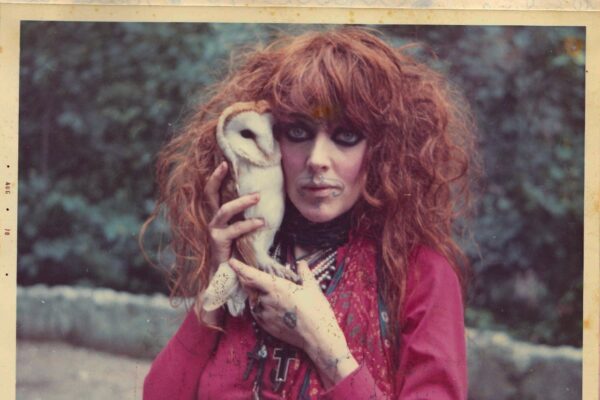

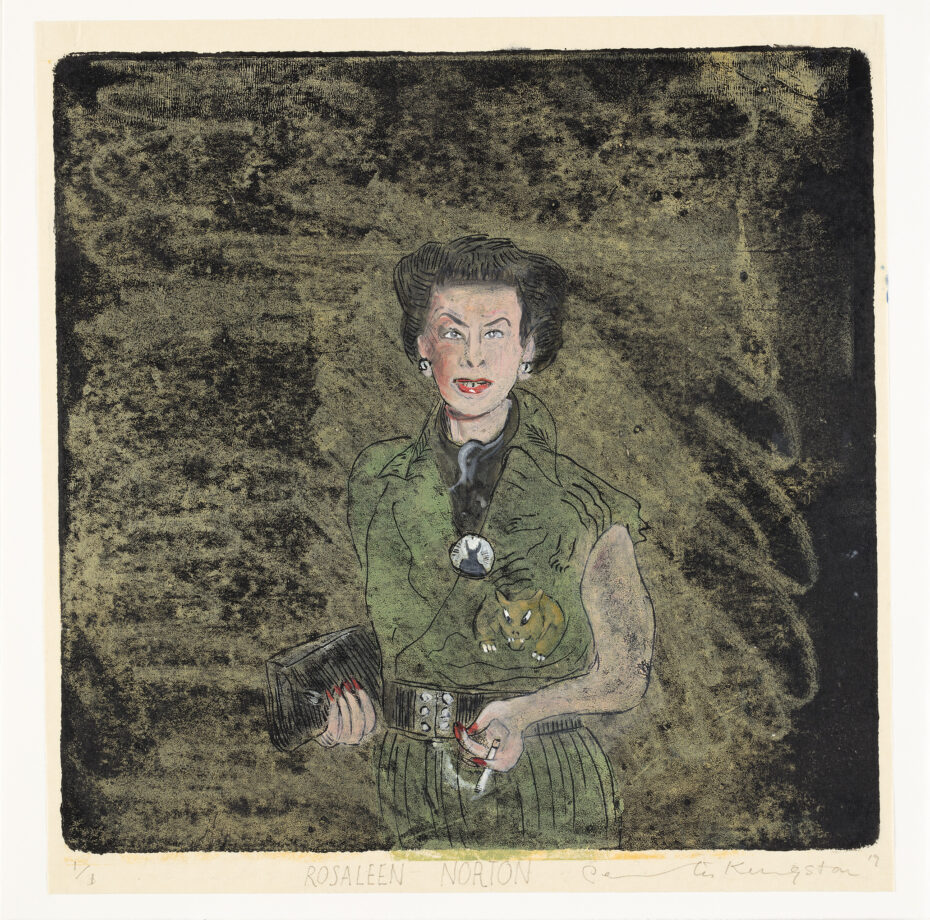

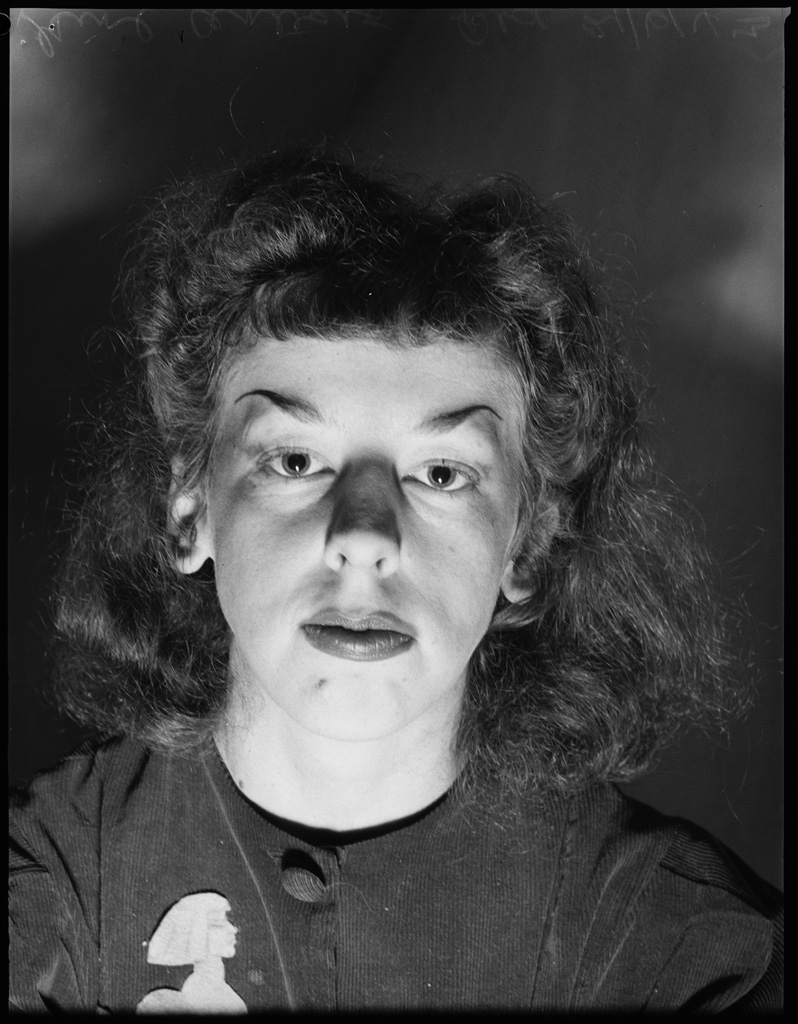

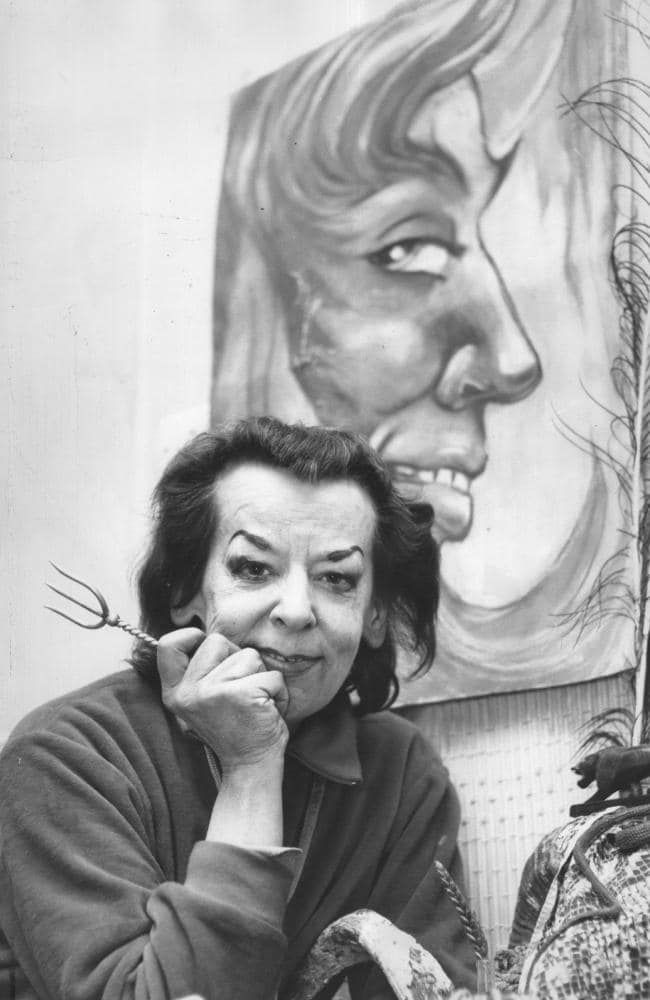

Meet Rosaleen Norton: artist, writer, pagan, devotee to Pan –a Greek god of the wild – but also a strong, sexually-active woman who was demonised by the media as the “Witch of Kings Cross”. Trapped in a conservative culture, Rosaleen decided something was a miss from a young age; she just didn’t feel like other children. Born in New Zealand in 1917 into a religious family, her imaginative and creative identity transcended the oppressive Christian direction of school and home. She moved out of the family home and into a tent in the garden for 3 years, creating a sacred space where she could manifest her curiosity about the veiled alternative, and rebel against what she saw as the oppressive norm. She collected an assortment of animals; a toad, a goat, lizards, a spider, the archetypal assemblage for any aspiring witch. By this time the family had moved to Australia where Norton found the culture as stifling as ever. She was expelled from school at age 14 for her prolific output of dark and demonic art, as viewed by the head of the Church of England school she attended.

Ostracised and oppressed, Rosaleen Norton was only just beginning to suffer at the hands of the establishment, but of course this wouldn’t be the first time someone declaring to be a witch – or even a little bit witchy, or basically being a little different – would be persecuted and tormented.

The casting out of Norton from this educational restraint found her in the very place she wanted to be; on the fringe of the preserved norm, she could now go and explore the arcane, the occult and strive for a creative freedom that wasn’t yet available for a woman in a restrictive society in the time she lived.

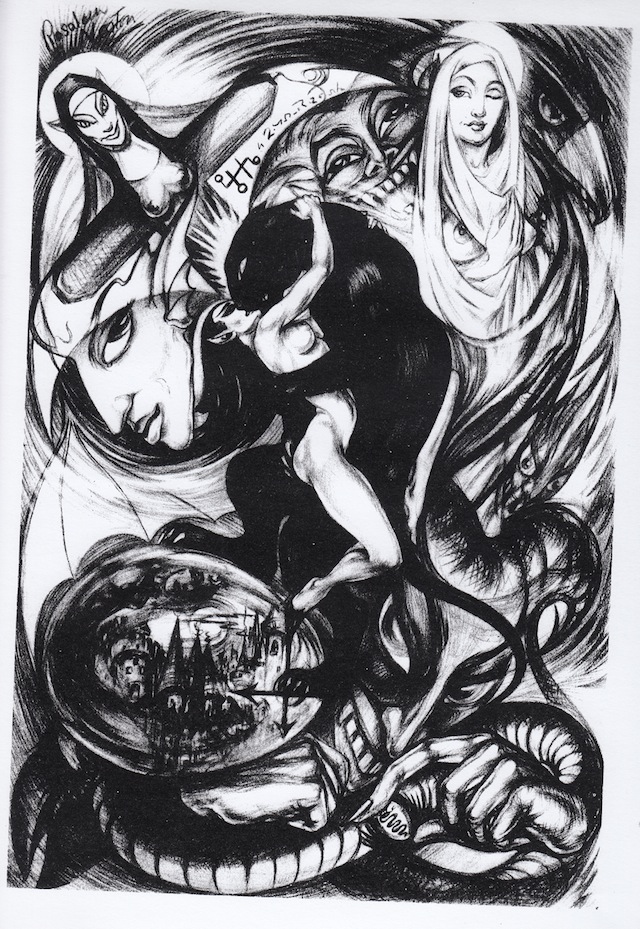

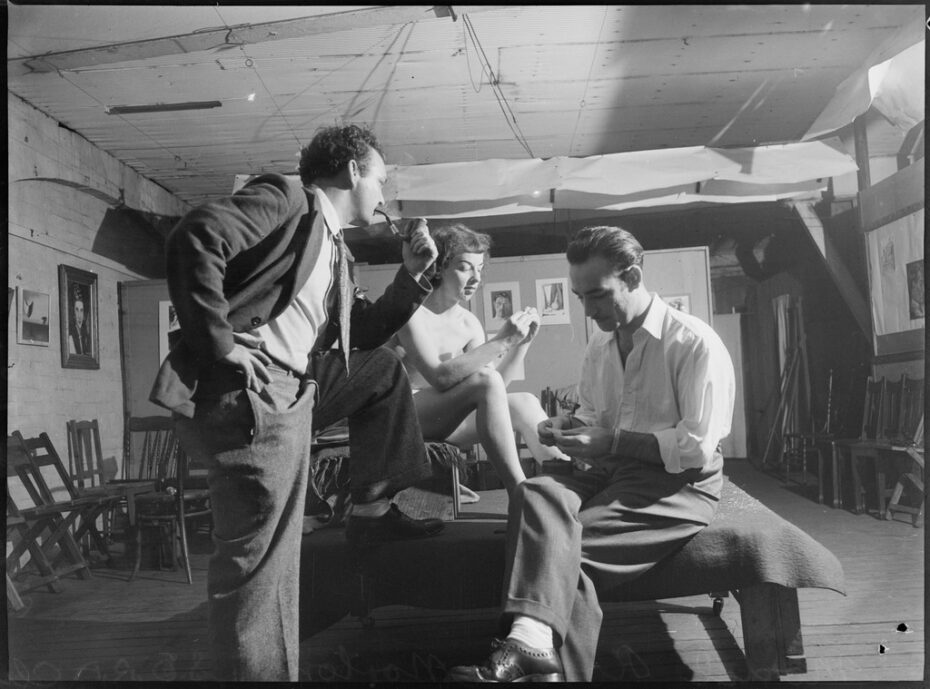

By the late 1930s, Rosaleen Norton had enrolled in art school, a sanctuary for the esoteric and eccentric. She produced dark intricate art, wrote and illustrated for magazines, worked as an artists model, and adorned herself in men’s clothing, all in the shade of black naturally, like a proto gothic art school vision. At 17, she had a brief marriage that ended when her spouse failed to come home from the Second World War. Her one dalliance into a so-called normal life had been brief. At this time, Norton began to explore the mystic with vigour; the allure of alternative spiritual paths, and the occult would become entwined with her outlook on the restrictive male-dominated autocratic society she found herself in. In contrast, it was a man whose writings would suit her expanding ideology the most. Enter Aleister Crowley, or “The Beast 666” as he had labeled himself, a British occultist, writer, poet, libertine, self-proclaimed prophet, and magician. Born in 1875, Crowley would have a significant influence on Western occultism and later, the 1960s counterculture. Norton would begin to explore his heretical doctrine of “Sex magic”, a ritualistic magical practice to transcend reality.

Her exploration of the outside only benefited her art practice, and she received acclaim from her peers at the University of Melbourne. In 1949, at a solo exhibition, police raided the show; most of her work was confiscated and destroyed due to what the police claimed was the obscene and satanic nature of the paintings.

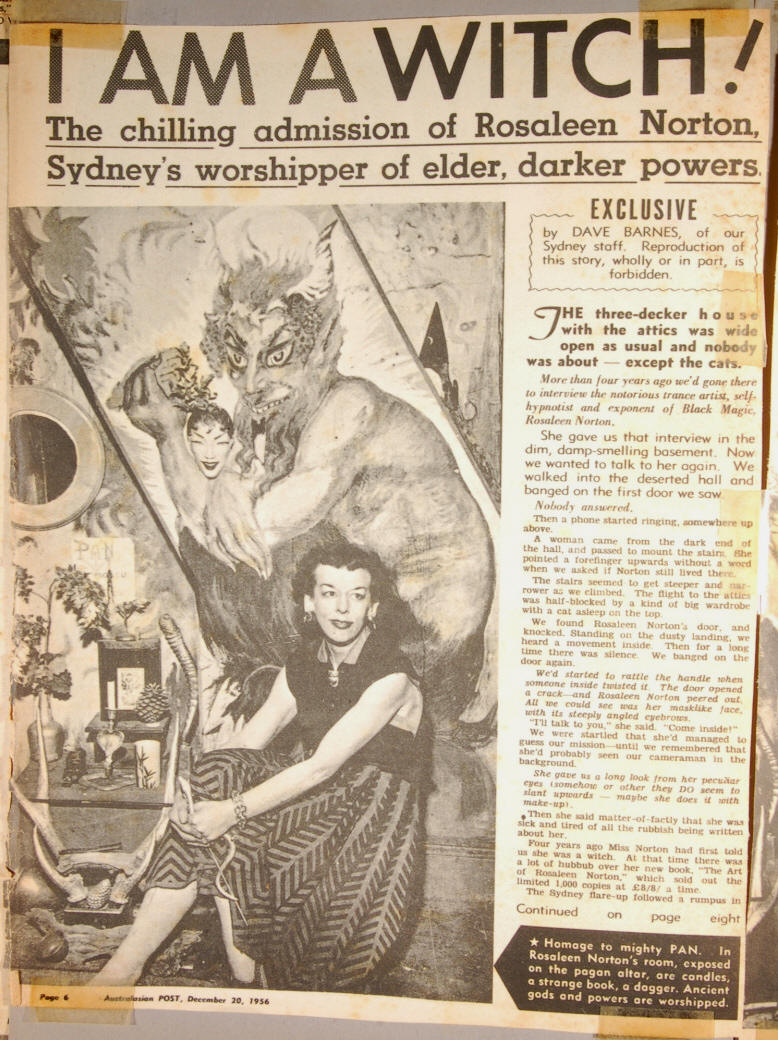

The case went to court and eventually, Norton would win and receive compensation from the police, but that wouldn’t be the end of the story. The press began to take interest in Norton, signalling the beginning of her troubles with the media and sensationalist tabloid headlines to come…

By the 1950’s, she’d moved into Sidney’s Kings Cross, an area of notorious repute at the time; a bohemian slum that harboured the city’s red light district. It had attracted artists, writers, and poets for its relative freedom from the usual restrictive society norms in Sydney. Norton and her now partner, Gavin Greenlees, a poet and exponent of Norton’s work and lifestyle, established a coven and further explored the occult, LSD, and their version of sexual freedom and progressive living. Without societal limitations, Norton was living in her own world, far ahead of her time.

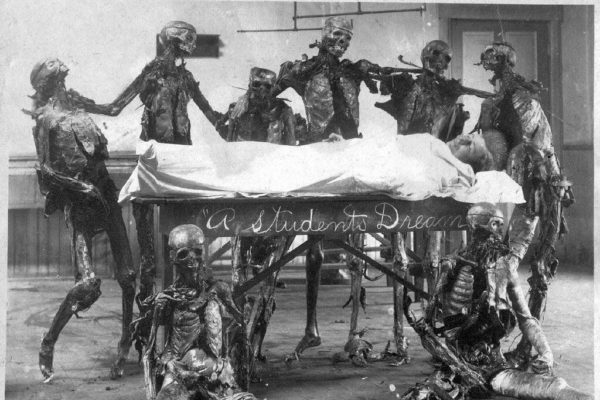

In Sydney in the 1950s, witchcraft was still illegal, and the law wouldn’t be changed until 1971 – some indication of the highly conservative climate of Southern Australia at the time. The more Rosaleen Norton expanded on her artistic freedom and magical practices, prompting a public outcry against her work, the more interest the tabloids took in slandering the name of this mysterious local witch.

She tried playing along with the attention, using it to her advantage to explain her beliefs in pantheism to the public via the press. But it only backfired. Instead, the press preferred to publish stories of animal sacrifice (which she vehemently denied and was very much against) and devil worship at Norton’s home. She became a local celebrity, attracting tourists to King’s Cross to find the famous witch, who had for the first time in centuries, written a full confession.

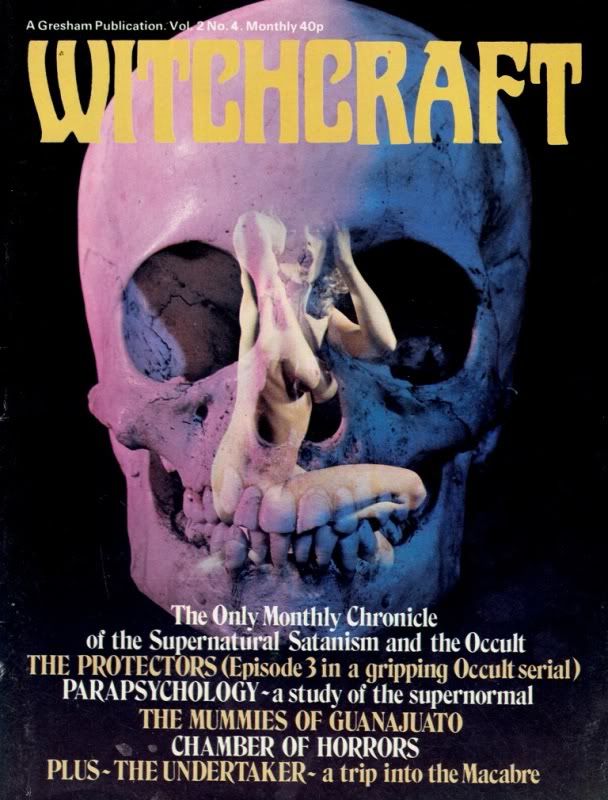

Fast-forward to the 1960s, a generation would be tuning in, turning on and dropping out in a new counter-culture. A youth movement would be experimenting with free love and communal living, and paganism would have a revival. People would clash with the establishment over freedom of expression and lifestyle. And at the forefront of this would be art. In 1967, The Beatles Sgt Pepper album was released, and who would be lurking on the cover, but the ‘wickedest man in the world’, Aleister Crowley. A year before, in 1966, hippie icon Donavon had released the single “Season of the Witch”. The Rolling Stones would follow suit with their ‘Satanic Majesties Request’, and a year later Black Sabbath would get together. The occult was in and becoming big business; films depicting paganism, devil worship, and witchcraft became popular at the box office. Books, and occultist paraphernalia would be sold in high street boutiques and the popular deity of the time would be replaced by the iconoclastic youth movement with a more free-thinking ancient band of idols.

By contrast, throughout the 1950s and later, Norton would suffer persecution at the hands of the authorities and the press. Their campaign of intolerance resulted in Norton being charged with vagrancy, as she wasn’t in regular employment. An art book bringing together some of Norton’s best pieces (The Art of Rosaleen Norton, compiled by publisher Walter Glover) was banned in Australia and denied importation to the US under obscenity laws. After a legal battle, the publisher was left bankrupt. When so-called friends sold private photos taken at Norton’s birthday party, police raided her home and charged her and Greenless for performing “unnatural sexual acts”. The establishment then went after Norton’s associates. A local business that was showing Norton’s work was raided. Folks looking to make a quick buck with the press used Norton’s name to fabricate stories about her, detailing black magic rituals and spells she had cast on them. Where 200 years earlier Norton would have been burnt at the stake, in the 1950s, the law sought to destroy her career and freedom of expression. Their modern day witch-hunt forced the talented and free-thinking expeditionary into social exile. Norton continued to live her life according to her beliefs, but she became reclusive in later life. Norton died in 1979.

Wicca is now one of the fastest growing religions in the world. Western universities have seen a dramatic rise in students identifying as pagan and joining or creating Wicca organizations on college campuses. In a world where digital connectivity has given a new platform to occultism, it might be “cool” to be a witch now, but it’s even cooler if you know your witch history, starting with the name that broke the barriers of conservative culture using art, sexuality and female magic. All hail the high priestess Rosaleen Norton.