When Parisian garbage collectors went on strike in the Spring of 2023, suddenly everyone was talking and thinking about trash. Sanitation and waste management services are so commonplace for the majority of the world, it takes an almighty “big stink” for us to realise just how important and valuable sanitary services are. Just under a century ago, our trash and waste looked very different than it does today. Before the invention of plastic, our waste was primarily composed of organic/biodegradable materials such as paper, plant fibres, and wood; disposed of out of city limits or naturally composted and used in farming. But there was (and still is) a category of materials and objects that were not organic waste, nor were they of great resale value, but they still had value as raw material or in trade. Enter the rag-and-bone man, a recognised but forgotten profession for most of the 19th and 20th centuries.

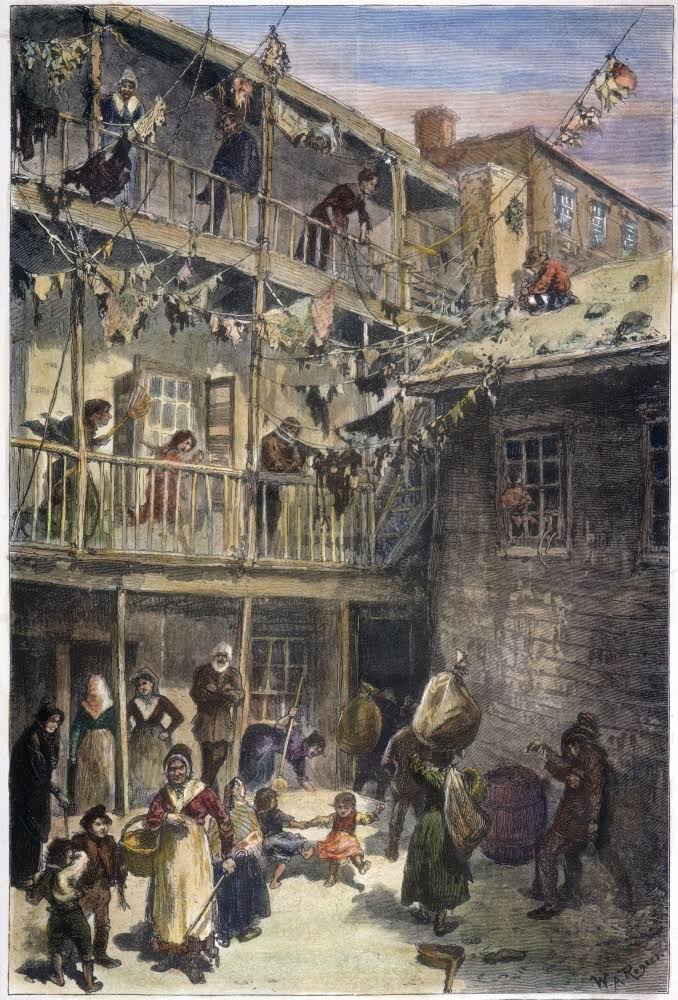

The rag-and-bone man, who could also go by other names (junkman, bone-grubber, bone-picker, chiffonnier, rag-gatherer, bag board, or totter) was born out of the industrial revolution, when materials began to be produced in greater quantities; new machinery was enabling the production of materials that previously were only made by hand and far more costly to produce. As materials such as glass, fabric, and iron come into production and wider public use, broken glasses products, scraps of cotton and wool, and metal scraps were collected by the local rag-and-bone man. At the bottom of the food chain, rag-and-bone men typically lived in extreme poverty, scavenging or purchasing their collections at a nominal price and then taking them to be resold to larger manufacturers or early “recycling centers” that come into being around the same time.

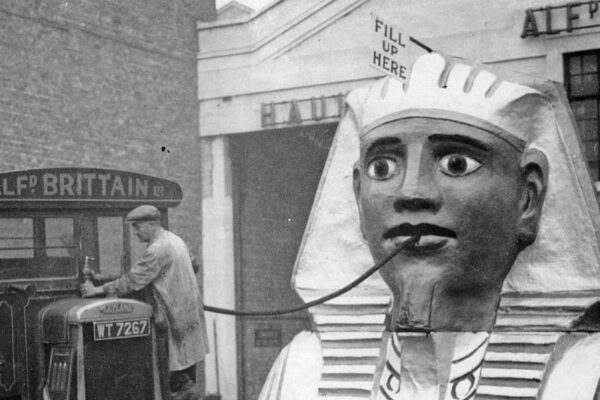

As the name intones, the rag-and-bone man could make use of scrap and waste that were seen as useless or unfit for use, including bones, feathers, fabric, glass, pebbles, metal of all kinds, and even leftover fats and grease. The rag-and-bone man was performed a noted necessary service that kept excess scraps and non-organic trash off the streets and out of already cramped inner city living situations. He was easy to spot, as he either worked with a horse and cart or walked up and down the streets carrying scraps in a sack carried over the shoulder. There are many accounts of the smell of the rag-and-bone man preceding him.

Even though the rag-and-bone man became obsolete as municipalities and governments passed waste laws and enforced management services, there are still some major cities in Europe where rag-and-bone men can still be found.

In the case of the alte zachen of Israel, this Yiddish version of the rag-and-bone man originated in Europe but is now an ubiquitous part of Israeli society. A profession born out a lack of options for Jews living in Eastern Europe in the 1800s, the alte zachen was a scrap collector in the style of the rag-and-bone man who would travel through the city streets by foot or with a cart and horse calling “Alte zachen, alte zachen!” which translates to “old things” in Yiddish. People would bring out their items to sell or scraps to give the alte zachen who would then resell them. Due to the violent pogroms against Jews in Europe during the 20th century, the alte zachen of Europe became the alte zachen of Israel and for many generations they continued their cart and horse trade.

The job of alte zachen was later taken up by Arab-Israelis who navigate their large trucks and vans through cities and villages in Israel today, yelling through a megaphone in a sing-song voice “Alte zachen, alte zachen! Shulhan, kisei, mekarer”, meaning “Old things, old things! Table, chair, refrigerator!” Some modern-day alte zachen use a recording of themselves that they play through a loudspeaker out of their vehicle windows.

The call of the alti zahen is now synonymous with Israeli culture and is somehow nostalgic and comforting in its Israeli uniqueness; much like the hollering of the fruit sellers in the open-air shukim in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. This indigenous form of recycling keeps untold amounts of recyclables, parts, furniture, and appliances out of Israeli landfills and is an unsung method of waste management that is often far more effective at repurposing and recycling than some of the larger-scale, more progressive waste management methods. Though the alte zachen is unique to Israel, this unorthodox approach to waste management and recycling has another home in the Middle East…

In Egypt, the Zabbaleen (which translates to “garbage people” in Egyptian Arabic) of Cairo is an important subculture in Cairo society. The Zabbaleen is a community of informal recyclers (the majority of them are Coptic Christian) but all of them live in the area known as Manshiyat Naser, located in the Mokattam Hills outside of Cairo.

Since the 1940s, they have played a crucial role in recycling Cairo’s waste with a unique, highly organised community-based system. Each Zabbaleen household is responsible for collecting and recycling one particular type of material such as paper, cardboard, glass, metal, plastic, or organic waste. This method maximises the amount of recyclable material that can be recovered more quickly. The Zabbaleen boast an impressive 80% material recycle rate by comparison to the 30% recycle rate of municipal waste management systems of Western and more developed countries.

Over the decades, the Zabbaleen have faced difficult working conditions and social stigma, often seen as being lower than the rest of society. Recent initiatives have sought to provide them training, equipment, and more social integration, but the Zabbaleen aren’t just a group of people who work together to survive, they are part of a deep and meaningful shared culture. In 2009, a charitable organisation was set up to support the community and in particular, help provide income-generating opportunities for the zabbaleen women who produce handloom rugs & bags, patchwork quilts using recycled materials.

In Manshiyat Naser, the Zabbaleen live in what’s known as “Garbage City” in the Mokattam Hills and it is in these hills that the Egyptian minority group of Coptic Christians (who are a part of the Zabbaleen) literally carved out their own place of worship. A series of interconnected caves that serve as chapels, prayer rooms, and community spaces, the cave church built into the rock face of the Mokattam Hills is the most significant place of worship for the Coptic Christians and the Zabbaleen community today.

The construction of the cave church began in the 1960s and was overseen by Father Samaan Ibrahim, a Coptic monk who initiated the project as a response to the growing Coptic Christian community among the Zabbaleen and their need for a place of worship. With the help of the Zabbaleen and other volunteers, the church was carved out of the mountain rock face over several years and dedicated to Saint Simon the Tanner, a Coptic Christian saint who lived during the 10th century AD and worked as a skilled tanner and is believed to have moved a mountain through his faith.

Today this unique place of worship is comprised of impressive multi-level chambers, the largest of which, the Virgin Mary Church, has a seating capacity of around 20,000 people. The Cave Church is an important symbol of the perseverance and unity of the Zabbaleen and the Coptic Christian community. Open to visitors, the Cave Church is not only a significant religious sight but also a testament to the cultural heritage of the Zabbaleen and much of vibrant artwork was made using upcycled materials).

In the annals of history, the rag-and-bone man may indeed be fading into obscurity as modern waste management systems take over. Yet, their contribution to society should not be consigned to the dustbin of forgetfulness. These unsung heroes teach us valuable lessons about resourcefulness, recycling, and the innate human spirit to make the most out of what others might consider worthless. Even in relation to something so dispassionate as trash and waste management, there is something about the analogous methods of performing tasks that create a distinctly human connection to them, conjuring up a nostalgia for a time when the world seemed more simple.