Unfathomably whacky fashions have seen the light over the ages. Take the perilous hobble skirt of the early 1910s that deliberately impeded its wearer’s ability to walk, or the gentleman’s codpiece that drew eyes to his genital area for most of 16th century Europe. We’ve dug up yet another surprising fashion trend of yore courtesy of none other than Mr. Benjamin Franklin. In the late 18th century, his invention of the lightning rod sent shock-waves throughout the the western world, so much so that society’s style mavens began sporting lightning rod hats in Paris and lightning rod umbrellas in London, convinced that their new-found accessories were not only fashionable, but functional. Introducing lightning rod fashion…

Benjamin Franklin: American polymath, writer, scientist, inventor, political philosopher, Founding Father of the United States and of … wearable tech? Picture him on horseback madly chasing around thunder and lightning and you’ve probably got a pretty accurate picture of Franklin on one of his 18th century storm-chasing missions. He was more than a little fascinated by electricity and spent the summer of 1747 turning his home into a makeshift laboratory, convinced that there were similarities between electricity and lightning and seeking a way protect people and property from its effects. In his now-famous kite-and-key experiment, Franklin attached a metal key to a kite, tied the kite string to an insulating ribbon for his knuckles and sent it off into the storm. As predicted the key received an electrical charge from the air, confirming Franklin’s belief that lightning was indeed a form of electricity. Having also deduced that by applying an elevated rod connected to earth, one may prevent the damage done by lightning, protective pointed lightning rods were soon installed across America’s public buildings and private homes.

“Would not these pointed rods probably draw the electrical fire silently out of a cloud before it came nigh enough to strike, and thereby secure us from that most sudden and terrible mischief”, Franklin said.

To further prove the credibility of lightning rods, and quite literally ride on the coat tails of Franklin’s research, numerous sartorial experiments proposed placing rods above a person’s head, concealed within a hat. A metal ribbon connected to a silver chain would wind its way around the hat, run down their back and drag on the ground. The idea was that, should lightning strike, the charge would travel down the chain and into the ground. This scientific fashion accessory came to be known as le chapeau paratonnerre.

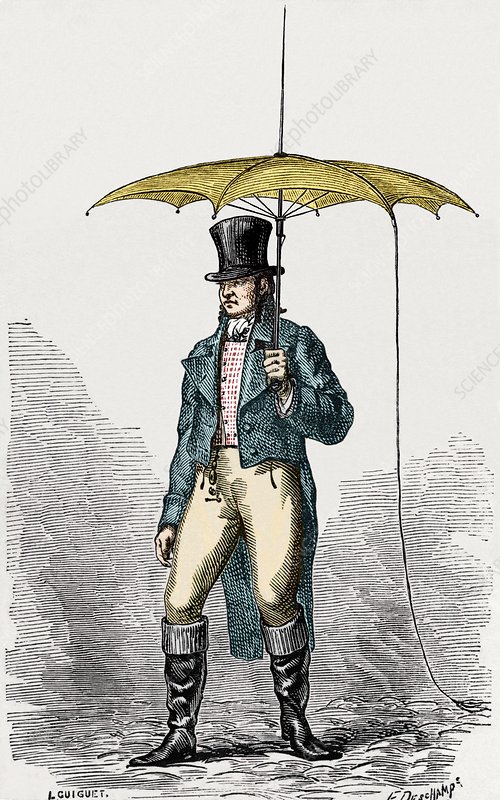

Another trend saw the umbrella, a key accessory of the fashionably dandy, fitted with a pointy metal rod at the tip, with a metal chain extending over the opened umbrella and down to the ground. This otherworldly contraption, proposed by one of Benjamin Franklin’s acolytes, Jacques Barbeu-Dubourg, was called le parapluie-paratonnerre.

From the light bulb dress to the galvanic belt, the lightning rod cap to the lightning rod umbrella, fashionable society was charged with an new electric glamour in the late 1700s. (As it turns out of course, neither sharp, blunt nor rounded ended metal rods make any difference in ‘attracting’ lightning). The hats and umbrellas were most popular in France, and particularly so in fashionable Paris. Franklin’s lightning rod technology and discoveries were a hot topic in European salons; electricity was a new, mysterious and magical force, an explosive, vigorous power that could also light up the world of couture.

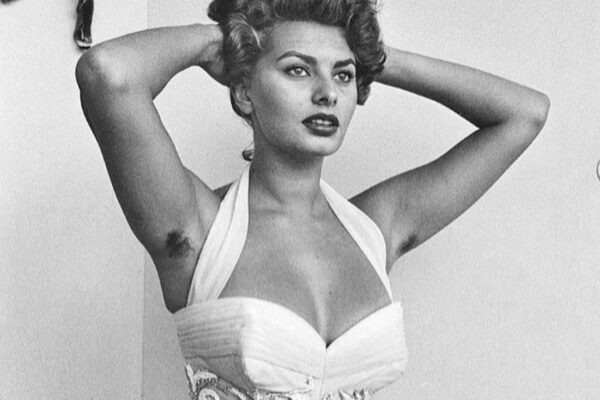

The Gentleman’s Quarterly (C.1745) announced with excitement, “Could one believe that a lady’s finger, that her whalebone petticoat, should send forth flashes of true lightening, and that such charming lips could set on fire a house?” Harnessing and discharging electricity became a popular party trick, like that of the Electrical Venus, where a woman would be charged with electricity and a member of the audience would be invited to kiss her, only to be jolted by the touch of her lips. Paula Bertucci writes, “Spectacular electrical soirees were frequently hosted in the darkened salons of aristocratic palaces where amazed spectators would see their hair rise, their silver-embroidered clothes glitter and their gold buttons spark, and other amusing effects of the electric fire.”

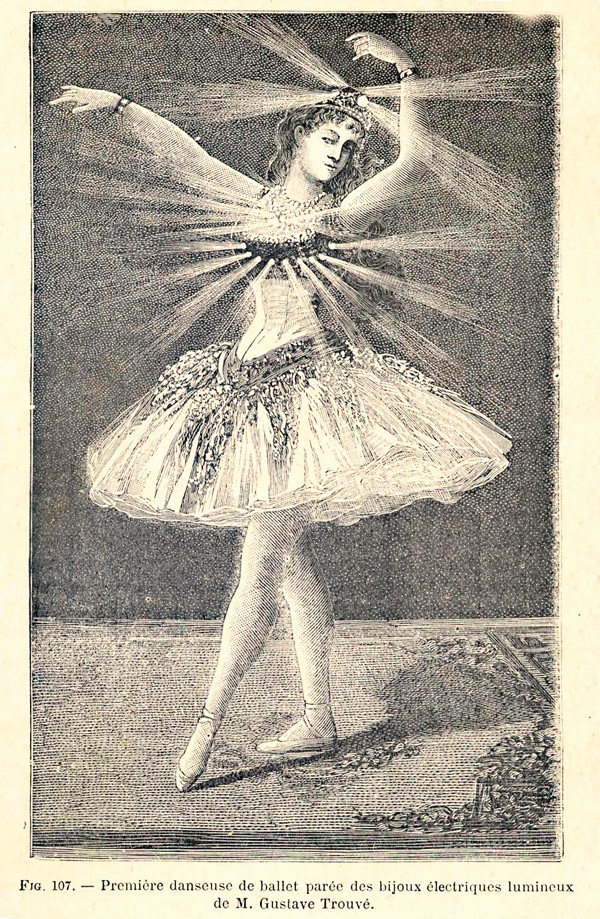

Electrical fashion took off in the mid 1800s after Gustav Trouvé’s invention of the pocket battery. Trouvé’s own bijoux electriques made their high society debut in 1879. Everything – from fashion to toys and torches – could now be glowing and sparkling, included Trouvé’s luminous walking sticks, a headlight tiara, electric flowers and luminous diamonds. In New York, society lady Grace Vanderbilt wore a gown inspired by electricity to the 1883 Vanderbilt Ball, with tinsel lights zig-zagging across the bodice and skirt. Allegedly the wife of a South Dakota electricity magnate was ‘wired’ from head to toe, wearing a fully wired gown, and when she theatrically stepped onto a copper surface, she literally lit up.

The Electrical World announced in 1897 that women’s bustles would be made larger to now accommodate batteries. “It is becoming more and more fashionable for ladies to wear electric jewellery, and room for it must be found in some portion of the costume… Any color can be got out of glass, for a tiny peep of light the smallest battery is necessary. A dashing demi-mondaine can thus make a pennyworth of glass eclipse a duchess’ diamonds or rubies. The correct thing now is to wear a star or brooch, illuminated by electricity, upon the left shoulder, instead of the diadems at first worn at fancy balls.”

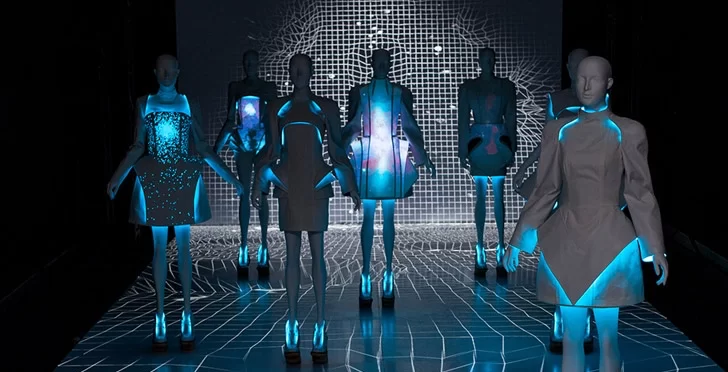

From the invention of the sewing machine to the dawn of wearable tech, technology has and will continue to seamlessly woven itself into the very fabric of our lives. We might snigger at the idea of lightening rod hats or the commotion that an electric tiara might have once caused, but these seemingly frivolous fads mark the birth of wearable tech and an ever-evolving partnership between fashion and technology. And in an exciting new era where fashion is becoming as much a statement of technology as it is of personal taste, there are undoubtedly many more “lightning rod” moments to come.