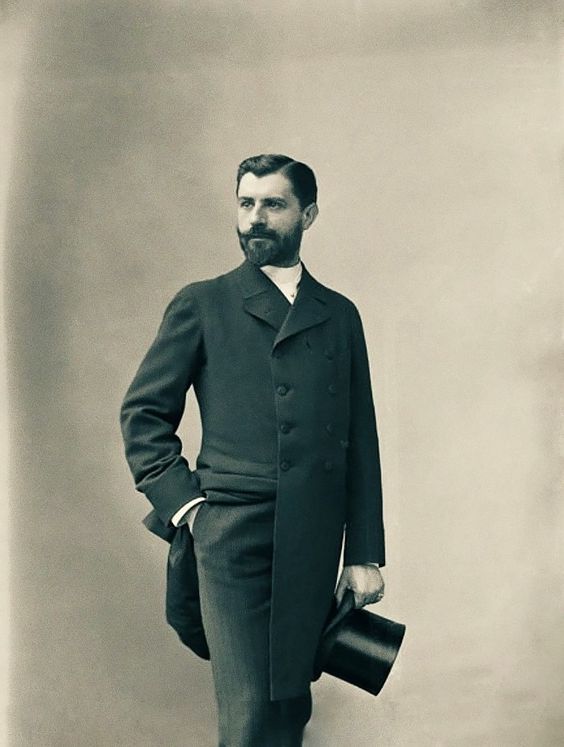

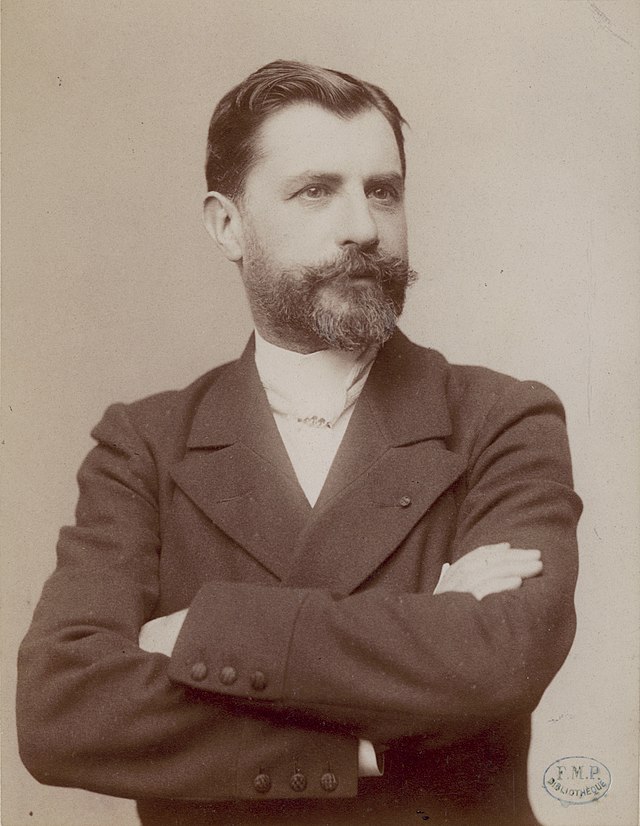

Dr. Samuel Pozzi may be a father of modern gynaecology, whose name is still tied to a pair of surgical scissors used to operate on fallopian tubes around the world today (the pozzi forceps), but his story would be much better placed in a steamy romance novel than a medical textbook. The “disgustingly handsome” celebrity surgeon, so declared by the Princess of Monaco, was chummy with the likes of Marcel Proust, Oscar Wilde, and the Parisian bohemian upper crust, and had so many high profile affairs, he earned himself the nickname “the love doctor” around town. Adding to our ‘who’s who’ of Belle Epoque Paris, let’s meet this irresistible ladies’ man, but also, remind ourselves why it’s never a good idea to date your gynaecologist.

We won’t bore you with a long list of medical accolades, but it’s worth noting that despite his colourful private life, Pozzi was a pretty brilliant doctor ahead of his time. He was a pioneer in the use of sanitary measures like antiseptic dressings and surgical gloves and took a more conservative approach to gynaecology, advocating for the least invasive solutions as opposed to readily butchering a woman’s uterus to merely cure a ‘nervous disposition’.

His 1890 Treatise on Clinical and Operative Gynecology laid out what has become the standard gynaecological examination, stressing the importance of making the patient feel comfortable and obtaining consent, a relatively unknown concept for treating women at the time.

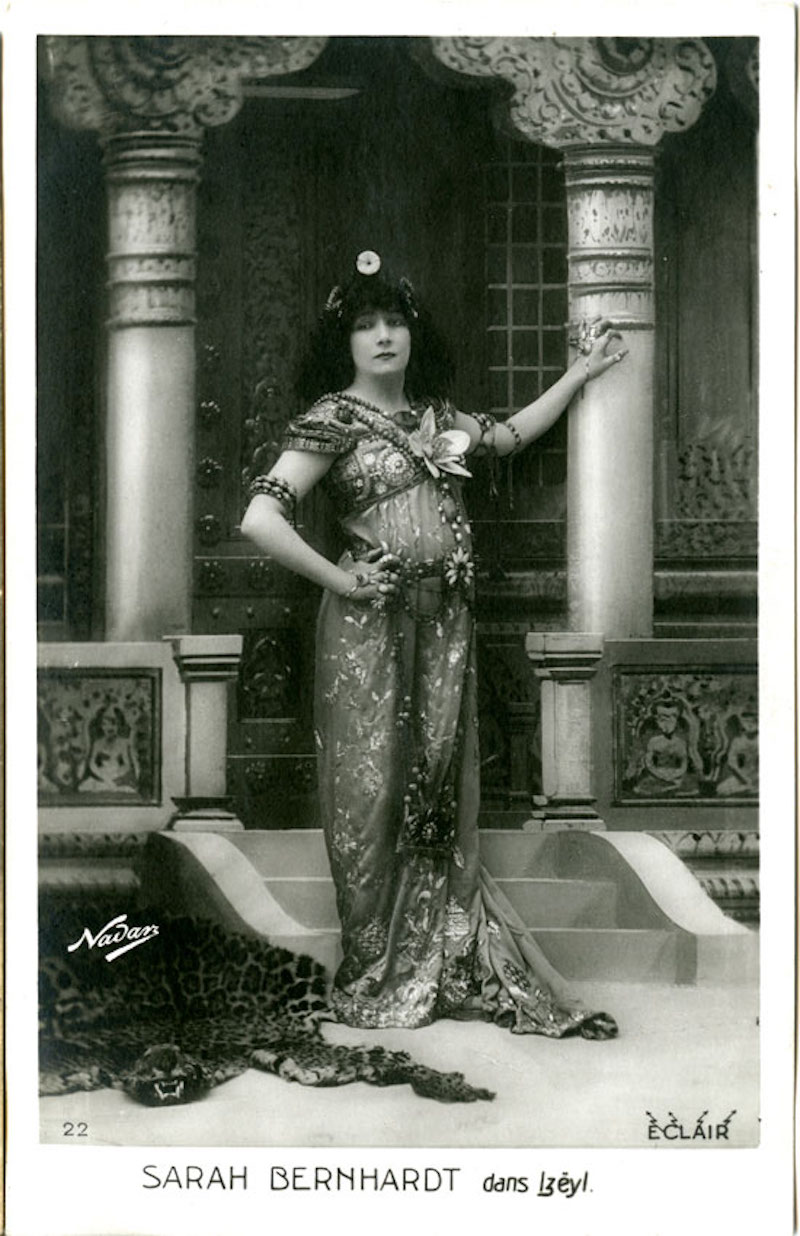

So attentive in fact, to the relationship between doctor and patient was Pozzi, that he was known to have affairs with his patients too. He had a wife, mind you – Thérèse Loth-Cazalis – a wealthy railroad heiress. But soon after the wedding, the relationship quickly turned sour, partly blamed on the fact that she brought her mother to live with them and their children, but nothing at all to do with his wandering eye, of course! His affairs became infamous and he particularly adored women of the stage. There was the opera singer Georgette Leblanc (sister of Maurice, who created the character of the gentleman thief, Arsène Lupin), the beloved and quintessential Parisienne, Réjane, and most famously Sarah Bernhardt, the star who conquered both the stage and film and became the principal muse to the burgeoning art nouveau movement. It was a passionate but non-exclusive relationship with Sarah that lasted over a decade. They remained lifelong friends and Pozzi ended up operating on a massive ovarian cyst she developed.

Dandy man about town, libertine, art collector, salon-goer, globetrotter and avid fencer, the tall, dark and handsome doctor was most definitely considered a catch in 19th century Parisian high society. Ever-immaculately dressed, he was painted as the ultimate ‘Casanova’ by John Singer Sargent, wrapped in his sumptuous blood red dressing gown. Sargent also painted a scandalous portrait of one of Pozzi’s lovers, the beautiful American socialite, Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau. In the delightful Belle Epoque novel I am Madame X, author Gioia Diliberto uses the voice of Gautreau to describe the painting of Dr. Pozzi, the city’s virtuoso gynaecologist, posing in his pyjamas…

On an easel near the French doors stood Sargent’s painting of Dr. Pozzi. It looked like a portrait of the devil. Virtually the entire canvas was red – the sumptuous curtains in the background, the carpeted floor. The doctor himself was dressed in red slippers and the red wool dressing gown that I had seen him wear dozens of times. His pose was hypertheatrical; his face was caught in an intense observance of an object outside the canvas, and his elongated fingers tugged nervously at his collar and the drawstring of his robe. His fingers were as sharp as pincers and seemed spotted with blood. Had Pozzi just performed a gynecological operation? Deflowered a virgin?

I am Madame X, Gioia Diliberto (2003)

It was Lydie Lemercier de Nerville, who hosted one of the most famed Parisian salons of the era, that crowned him “Doctor Love,” based on the title of a play by Molière. Bernhardt simply called him “Doctor God”. Despite his closeness with the actress, Pozzi’s longest affair, which lasted until his death, was with the wealthy socialite Emma Sedelmeyer Fischhof.

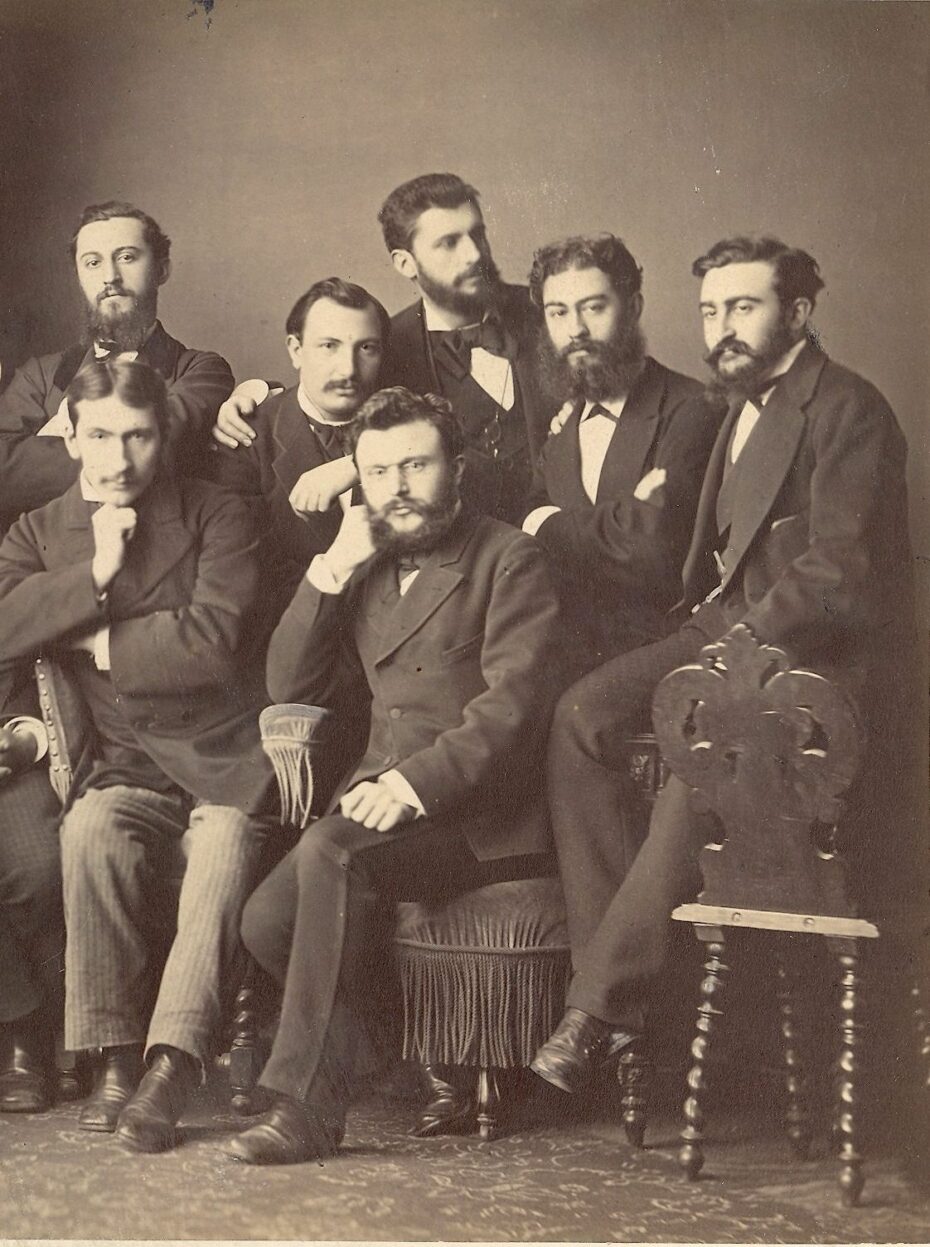

And as his fame grew, Pozzi found himself at the highest ranks of the medical field as a gifted surgeon. His patient list, including Robert de Montesquiou, Prince Edmond de Polignac (two of his closest friends) and members of the Rothschild family. He was a devoted doctor who didn’t hesitate to operate on patients in his home, accompanied by his faithful assistant, Robert Proust, the brother of Marcel. As a close friend of the Proust’s, Pozzi is thought to have been the inspiration for “Doctor Cottard” in Marcel’s prominent novel, In Search of Lost Time.

While he wrote some 400 medical papers and invented numerous surgical devices (including pliers and syringes that are still used today), Pozzi’s views on feminism however, have not aged well. He believed in fundamental biological differences between men and women that he claimed destined them to work in separate fields, and consequently dissuaded his own daughter Catherine from entering medicine as a profession. In her journals, she described the suffering she experienced due to her father’s convictions about the “lesser sex” which he so tenderly treated in his practice, but refused to envision a future in which women played a meaningful role.

“From interns, women will be able to become heads of clinics, then heads of departments and judges of competitions. That’s not all: armed with an invincible analogy (which they already invoke) they will demand entry into other careers …”

Samuel Pozzi

As Pozzi’s biographer, the gynaecological surgeon Claude Vanderpooten, wrote, “He loved women passionately like everything that is beautiful. He devoted his life to them.” In many ways, Pozzi made women’s lives undeniably better at a time when they were just as likely to be used as surgical guinea pigs as they were to be treated. Is it appropriate to judge Pozzi by today’s standards? We may not necessarily have to…

The grandson of an Italian immigrant, orphaned by his mother at ten years old, Pozzi had cut across impenetrable lines of French high society to enjoy a very privileged life alongside Parisian aristocracy, and even briefly played a role in politics as a senator. During World War I, he became a hero for his role as a surgeon on the frontline and led an adventurous, cultivated and amorous existence – until he ended up getting murdered in his own consulting room.

On June 13, 1918, Dr. Pozzi was killed by Maurice Machu, a former patient who he had treated for an enlargement of the scrotum. Machu believed the surgery had made him impotent. When Pozzi disagreed, suggesting he was “suffering from a nervous complaint,” Machu shot him three times before turning the weapon on himself.

John Singer Sargent’s striking 1881 portrait, Samuel Pozzi at Home, hadn’t been seen by the public in nearly a century when it was transferred in 1991 to the Hammer Museum of Los Angeles, where it hangs today. Oil magnate, Armand Hammer (great-grandfather of the disgraced actor Armie Hammer) had acquired it from descendants of Pozzi in 1967. While Pozzi may have promoted the chauvinistic values of his era, one might agree it’s refreshing to encounter a dandy of 19th century France whose name isn’t Baudelaire, or Proust or Wilde. This forgotten bon vivant of the Belle Epoque is the subject of a recent 2019 biography which the author Julian Barnes readily confesses is a “collection of holes tied together with string”. The Man in the Red Coat is full of swashbuckling tales from the beautiful French epoch and asks the all important question: “Do gynecologists make better lovers?”