So it turns out, the famous “free love” movement of the 1960s, wasn’t so free – what with a total lack of information and availability of birth control. With the youth movement came a dramatic rise in unintended pregnancies. Abortions were illegal and carried a life term in prison; the birth control pill was only available by prescription to married women and even the advertisement of contraception to the public was deemed illegal by the government under the Comstock Act passed in 1843. Meanwhile, a group of teenage students at McGill University in Canada decided to take matters into their own hands…

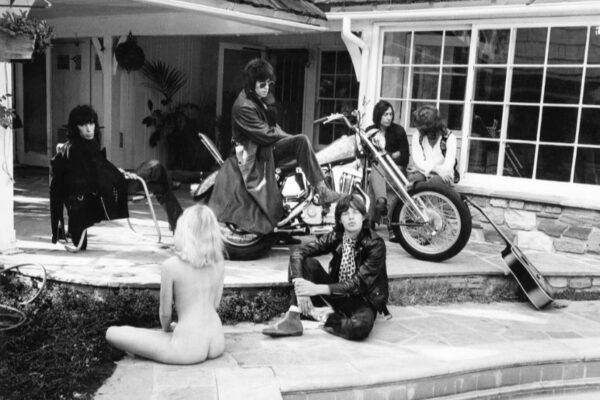

The 1960s saw a cultural and social sea change, the post-war baby boom had seen a generation grow up in an optimistic changing society. Rock and roll had been the soundtrack of the burgeoning youth and a newly found freedom of the teenager had a voice for the first time and they wanted to be heard. The counter-culture tuned in and dropped out, and sexual liberation would see a generation experiment with their sexuality and each other.

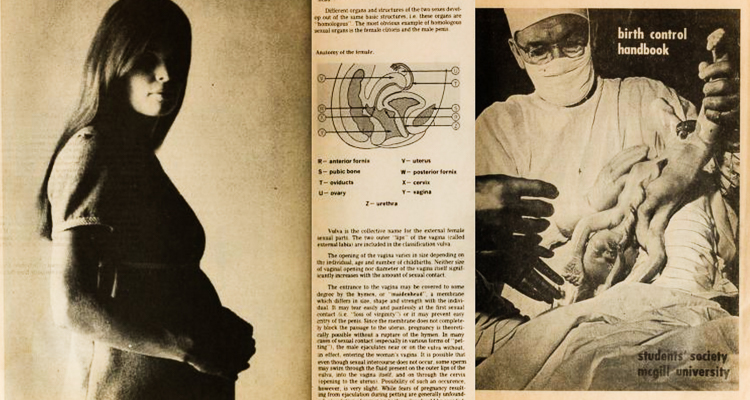

In 1967, a 19 year-old sociology undergraduate and student council vice president at McGill University, Peter Foster, moved to arrange a seminar on sexual education and to open a birth control clinic on campus. The committee also decided to produce a birth control handbook offering all the information that could not be found easily anywhere else. This handbook would have a significant impact not just on campus, but would spread throughout Canada and America and give a much-needed source of guidance and information to the newly liberated youth. The original co-authors of the handbook were editor-in-chief, Allan Feingold and his partner Donna Cherniak, both undergraduates and art students. They would go on to put thousands of hours of work into the production of the first edition. They studied medical texts and consulted sympathetic physicians to accurately relay important information in a language that could be understood by everyone.

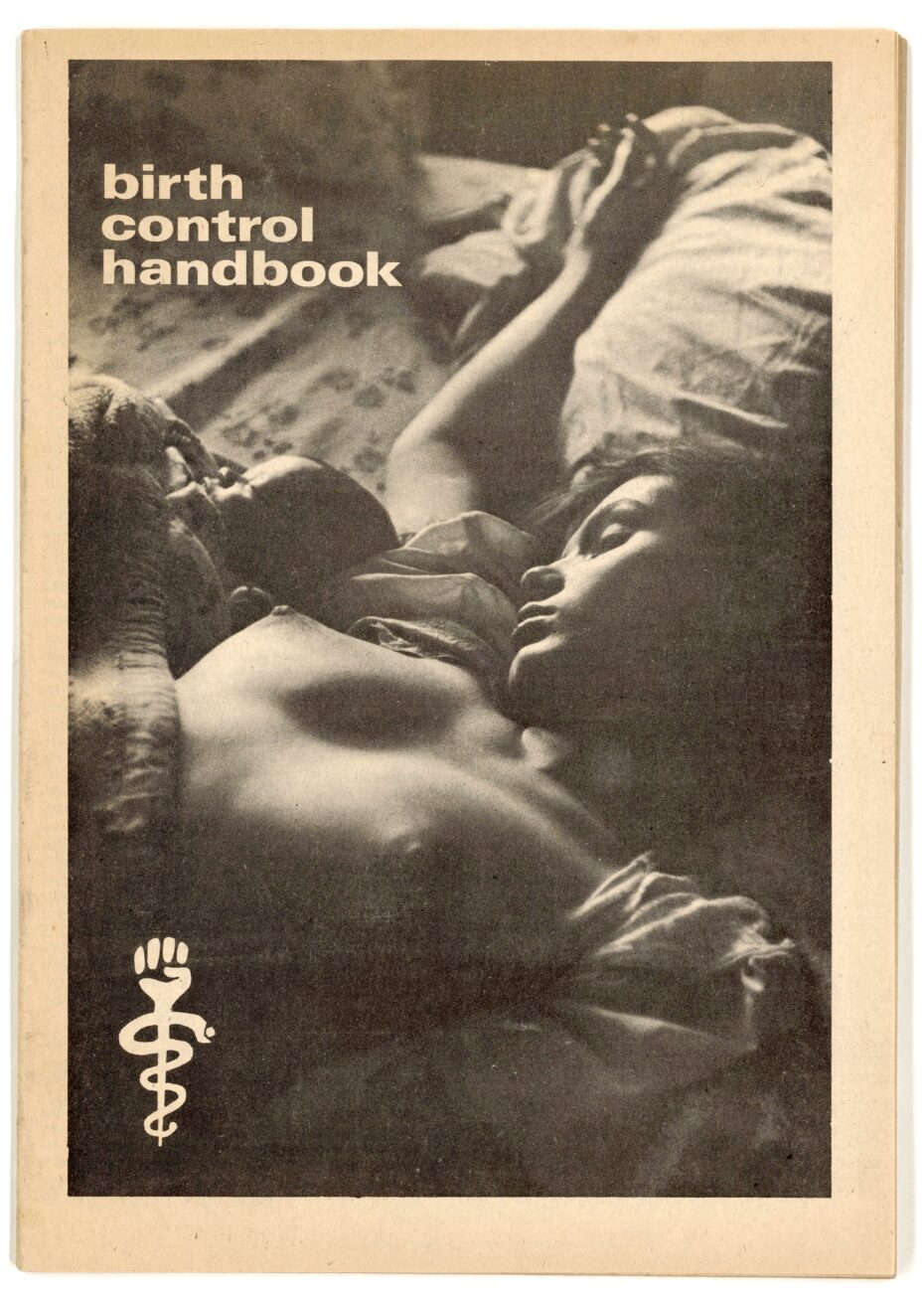

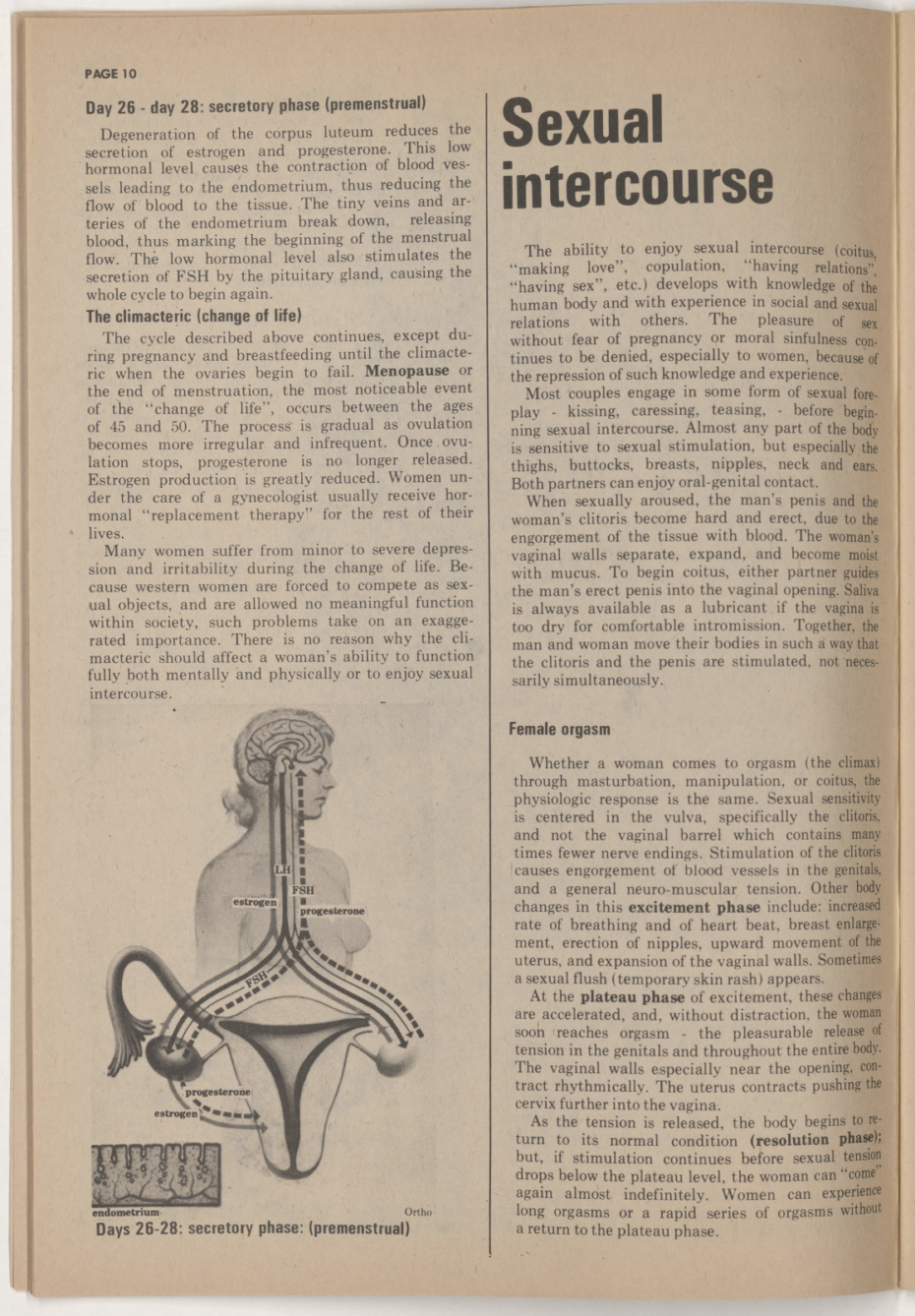

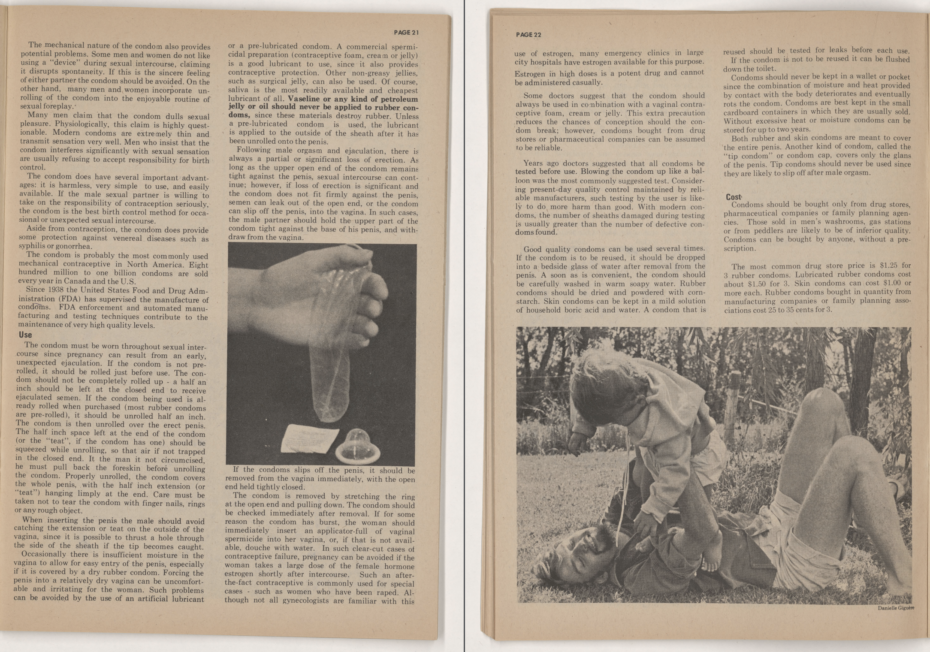

In addition to some fairly graphic imagery for the time (including a photograph of a baby’s head crowning during childbirth, page 13), an illustrator was employed to better visualize anatomical diagrams in a less cold and scientific form. Funding would come from McGill and 10 other universities that recognised the need and significance of the Handbook. They chose a black-and-white format to be printed on newsprint to keep the costs as low as possible. But still, the archaic criminal code hung over the project, which didn’t seem to worry vice president Peter Foster.

“We figure if we get a lawsuit it will be a lot of fun,” he commented in 1968.

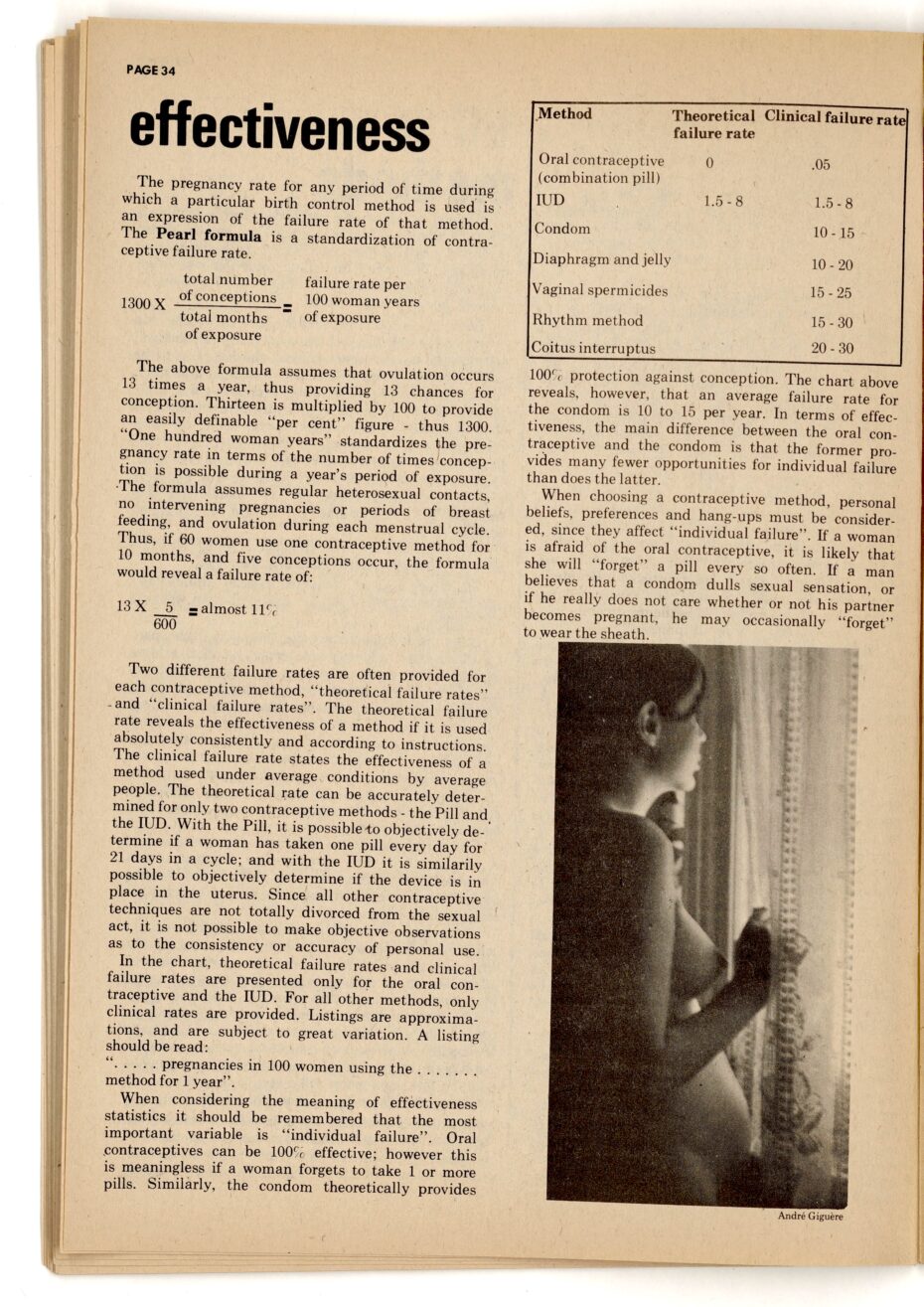

The First edition of the Handbook would contain sections on different types of birth control then available and how to use them correctly, including diagrams of the reproductive system, information on abortion, and the current laws surrounding it, all with an editorial sway towards the Women’s Liberation Movement. Feingold and Cherniak had realised the sheer lack of accurate sexual health and birth control knowledge out there amongst their own generation. Until then, myths and rumours and schoolyard spiel made up the majority of information their peers held. The McGill University newspaper pronounced they hoped the Handbook would “bridge the gap between high school hygiene courses and street corner advisory sessions”, The McGill Daily reported in 1968.

The first run of the Handbook totaled 17,000 copies, mostly printed from Feingold and Cherniak’s apartment in Montreal. They had sacrificed their own studies to get the handbook out there, and they were only going to get busier. A second edition followed in 1969 and requests started to come from all over America as well as Canada. From 1969 to 1970, 300,000 copies were distributed. Feingold and Cherniak stipulated that the handbook be distributed for free in universities and they hoped in schools one day. Not every educational institution and city was as open-minded though. Florida banned the handbook, as did Missoula, Montana, and Pembroke, Ontario. Princeton University’s health organisation had mailed a copy out to each student and landed itself in a scandal that was covered by Time magazine. Many conservative students and staff had taken offence to the publication and its leftist leanings and anti-American imperialism stance and the handbook’s authors were labeled as Maoists and Canadian communists. Undeterred, the handbook would continue to be revised and updated, with newly added content about overpopulation, racism, colonialism, and the women’s liberation movement as well as more up-to-date information on sexual health and birth control.

‘We were not doctors, we were not medical students even, and we spent a month studying enough to produce the first edition of the Birth Control Handbook, and we tapped into this huge demand that we actually didn’t fully appreciate,” said Feingold to the McGill Tribune.

The aesthetic appeal of the handbook may have been another factor of its popularity. Feingold and Cherniak were art students who had tapped into a graphic photographic style to juxtapose the medical text. In 1971, the handbook sold 2 million copies, it had become wildly popular, and Feingold and Cherniak had begun to receive mail and phone calls from women desperate seeking advice for unwanted pregnancies. They decided to set up an abortion referral service out of their apartment with the help of a math Professor, Donald Kingsbury. “We had two things going at once, we ran the distribution of the Handbook and the abortion referral service”, said Cherniak at the time.

The Handbook would go on to sell millions not just in the US and Canada but worldwide,. Feingold and Cherniak moved onto medical school and relinquished control to others who continued to distribute it. Many other publications on birth control and sexual health would follow in the wake of the Handbook but none quite as popular or groundbreaking as the Birth Control Handbook that was started by a group of teenagers in Montréal in 1968.