Perhaps you remember the feeling of unearthing a really great gem at the record store – a forgotten band from another time with an original sound that sends those feel-good electric impulses to your brain. Imagine making it your lifelong mission to find that feeling; following it far past the local record store, to the remotest corners of civilisation. Alan Lomax, like his father before him, spent his life on an odyssey of unrecorded sound, searching the world for the essence of music and lost songs of isolated cultures. He was a musical prolific anthropologist and folklorist and would go on to make more than seventeen thousand field recordings of singers and songwriters. He would discover blues musicians such as Lead Belly and Muddy Waters, champion the folk singer Woody Guthrie, and travel to Ireland and the Outer Hebrides in Scotland to record traditional music from forgotten sources. He documented working music, walking music, dance and spirituals, songs of lost loves and hardship, and oral storytelling used to transfer knowledge and history to the decedents of disappearing cultures.

‘The essence of America lies not in the headlined heroes…but in the everyday folks who live and die unknown, yet leave their dreams as legacies’

Alan Lomax

Lomax believed that the music coming out of a plantation in the American South or from a tiny village in the remote mountains of Europe was equally as important if not more than classical compositions produced by history’s most famous musicians. A historian of song and story, he would work for the Library of Congress like his father for many years before starting his own organisation when congressional funding was cut. The importance of his research and musical legacy would be hard to quantify – if Bob Dylan hadn’t heard Woody Guthrie or the Beatles hadn’t heard British artist Lonnie Donegan covering Lead Belly’s songs, what would be the shape of music today? If music and song have a linear progression that we can trace back to the source, what if we were to sever that link?

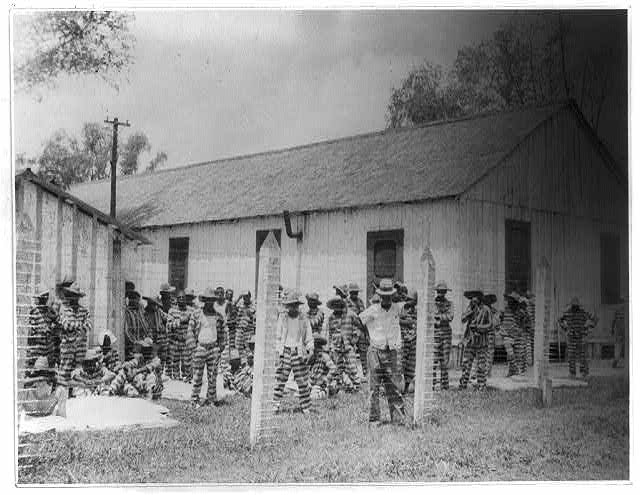

In 1933, a father and his 18 year old son loaded their car with recording equipment in 1933 to seek out folk and blues musicians in the American Deep South, setting off on an exploration into the unknown history of the song. Alan’s father, John, had already been writing and collecting knowledge about frontier music and cowboy songs from the American South since he was a boy. Born in Mississippi in 1867, he’d grown up working on his own father’s farm, where he would befriend an African American worker and former slave called Nat Blythe, who taught John the songs that had been passed on to him by his ancestors. In return, John taught Nat to read and write. This would sew the seeds of the beginning of the nomadic Magnus opus of the Lomax family. John would stay on the farm until he was 21 before enrolling in a rural college and becoming a teacher and later earn a place at Harvard. While there, he would share his knowledge and passion for folk music with two of his professors who encouraged him to continue his research into the origin and history of cowboy songs. After founding the Texas Folklore Society, he went to Washington to begin work for the Archive of American Folk Song. This is where he would secure recording equipment and set out the plan of his odyssey into the backwaters and isolated communities that were yet to be affected by progressivism, and still preserved their cultural history with music and song.

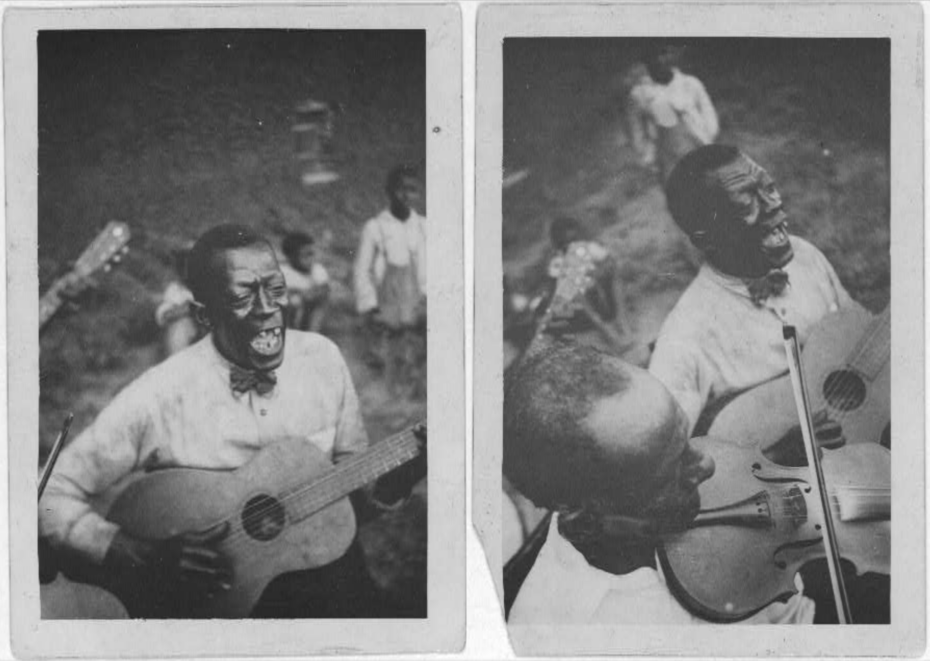

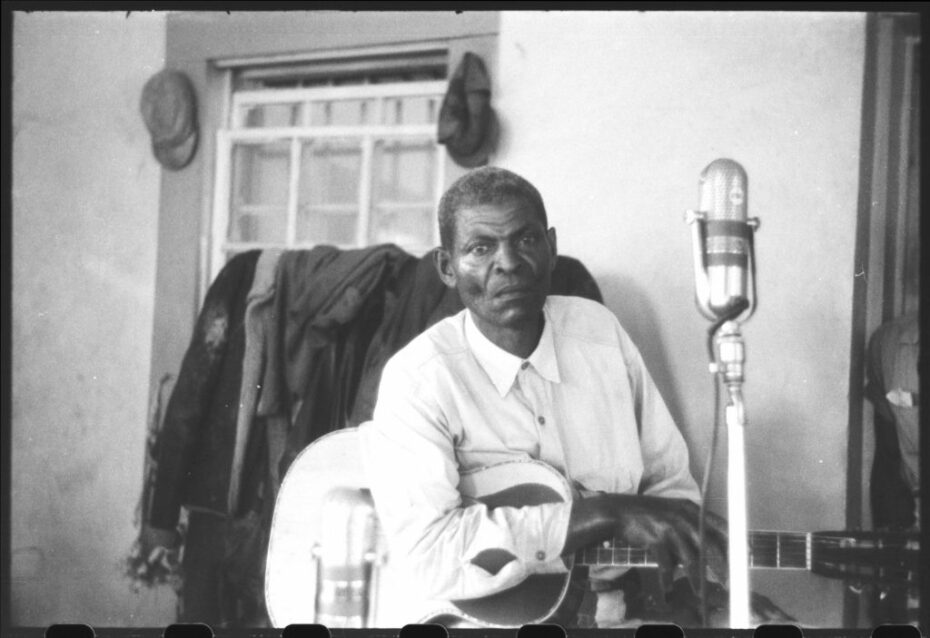

While visiting Louisiana State Penitentiary, an 18-year-old Alan would first hear Huddle Ledbetter, known in popular musical history as Lead Belly an early pioneer of folk and the blues. They had been touring prisons in the south recording prison work songs and chain gang music, the call and response to rhythmic hard labour performed to endure the harsh conditions. Alan was captivated.

‘He sat down in front of us and proceeded to sing everything that we could think of in this beautiful, clear, trumpet-like voice that he had, with his hand simply flying on the strings. His hands were like a whirlwind, and his voice was like a great clear trumpet. You could hear him, literally, half a mile away when he opened up.‘

Alan Lomax

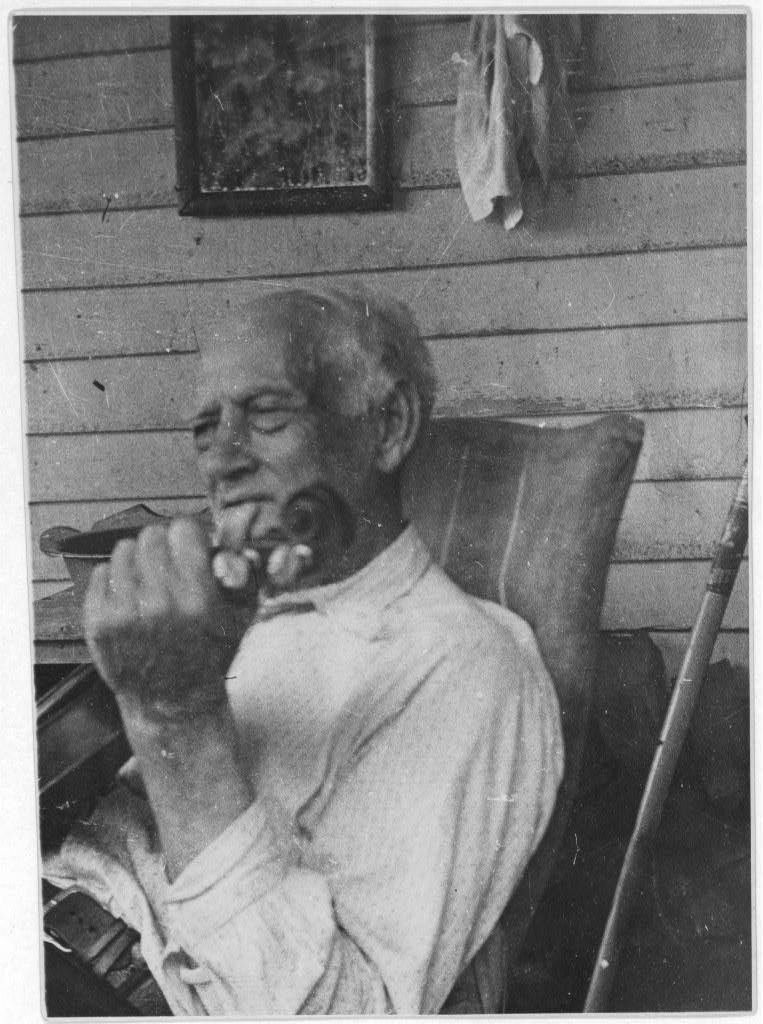

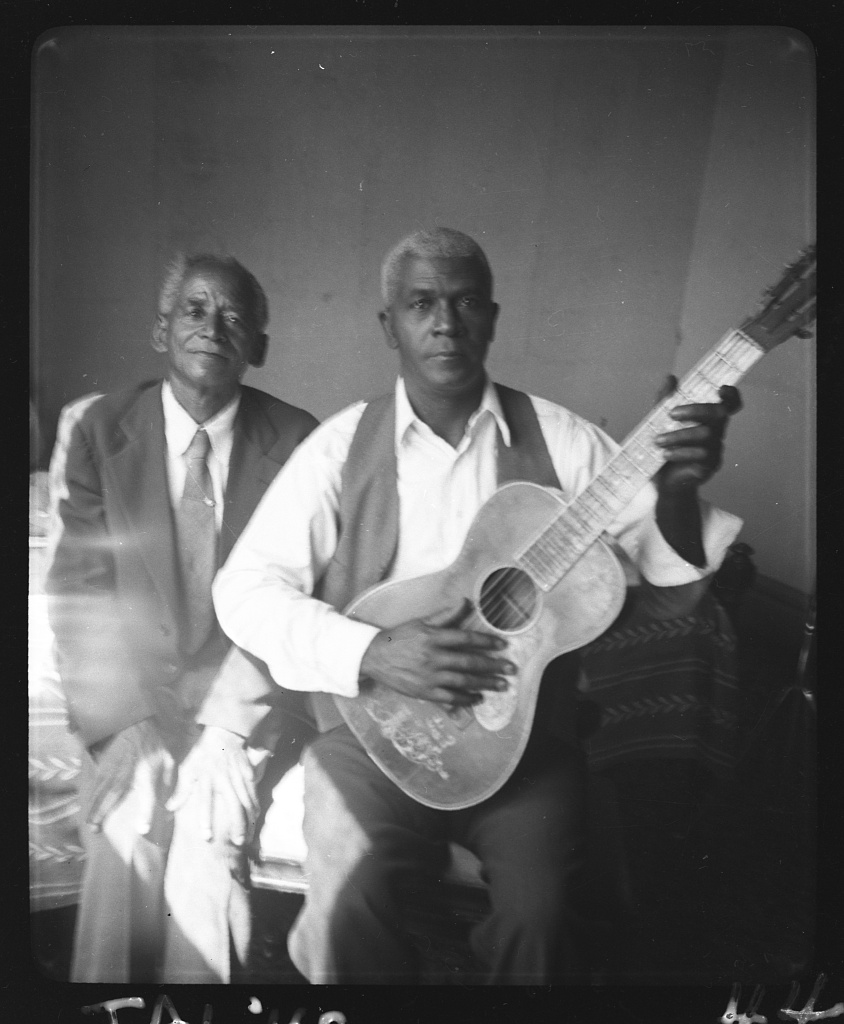

Lead Belly in prison in Louisiana, photographed by Alan Lomax, 1934

Lead belly would prove an important addition to the archive and catalyst for popular music, remembering hundreds of folk songs he’d heard and learned from childhood. Lead Belly was released from prison a year after the Lomax’s visit.

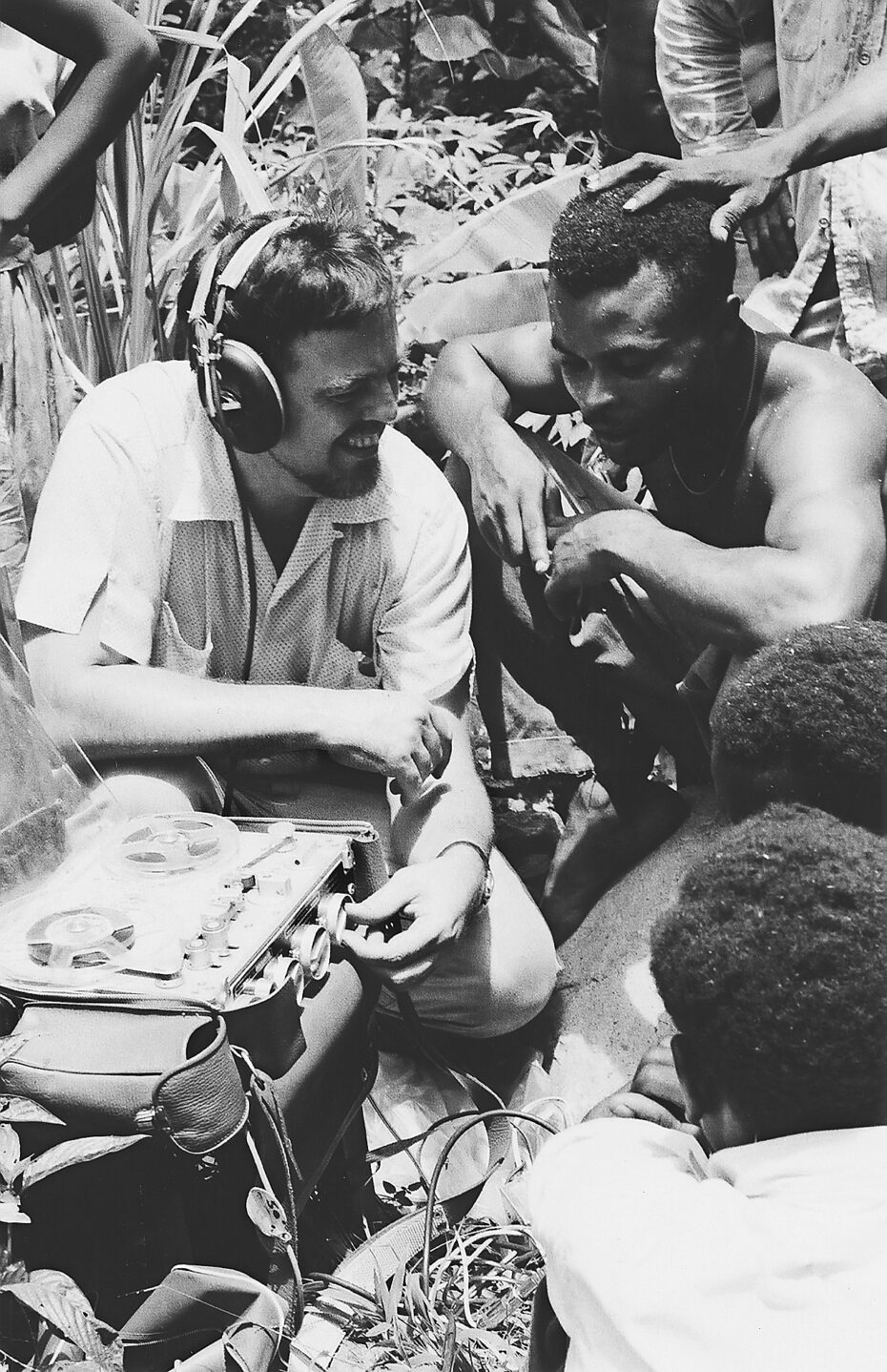

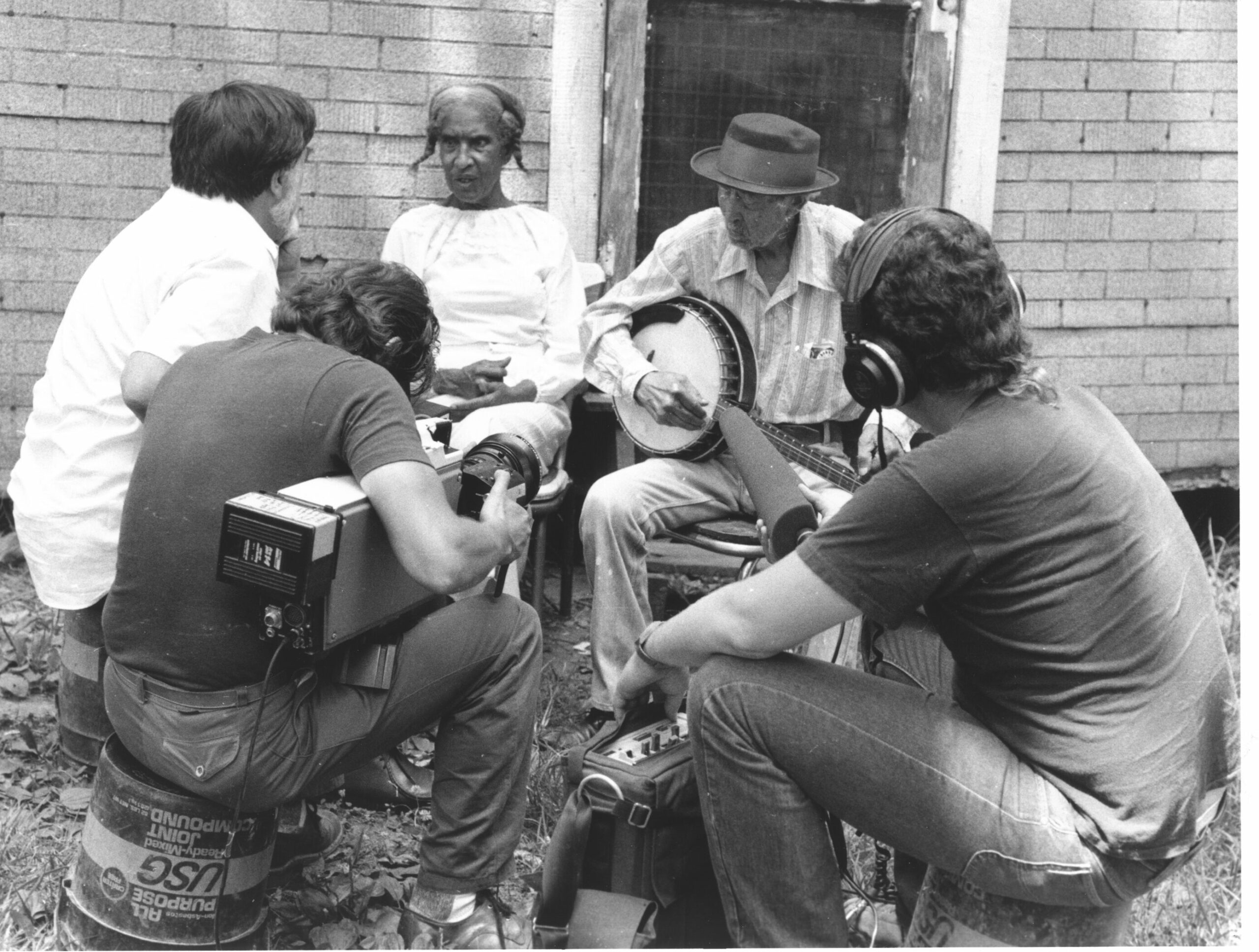

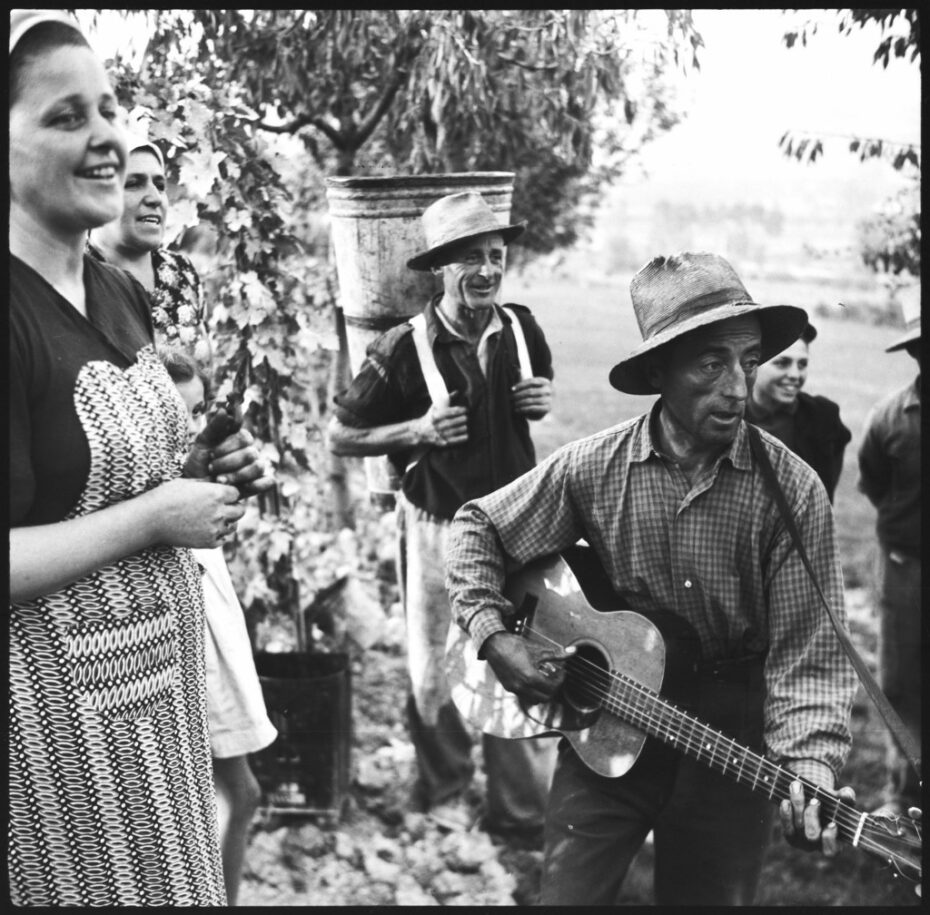

The Lomax’s would travel around the back roads stopping in rural locations, asking workers and residents if they knew of anyone that sang songs and played instruments, going from one musician to another, following clues and tip-offs. They carried early cumbersome recording equipment that filled the back of the car to capture the songs and interviews with the performers, trying to learn the history of the music, how the instruments were played, and gain insight into what the songs were about. Most participants in the recordings had never heard themselves perform before.

By 1935, Alan was also working for the Library of Congress and conducting his own solo field trips. Born in 1915, Alan had suffered from Illness most of his childhood and had been home-schooled. He would develop his love for folk music and shared his father’s passion for cultural creativity, as well as historical classification of indigenous songs. After negating to go to Harvard as his father wanted, Alan set forth on the path of cultural enlightenment just as John had done before him. The long road that Alan would take would differ from his father in some respects; Alan would have a more defined view of the Civil Rights Movement, multiculturalism and carried an attitude and sensitivity that would define his relationships with the people he recorded.

‘And the thing that I always tried to do with important singers when I met them was to sit down and record everything they knew, give them a first real run-through of their art.’

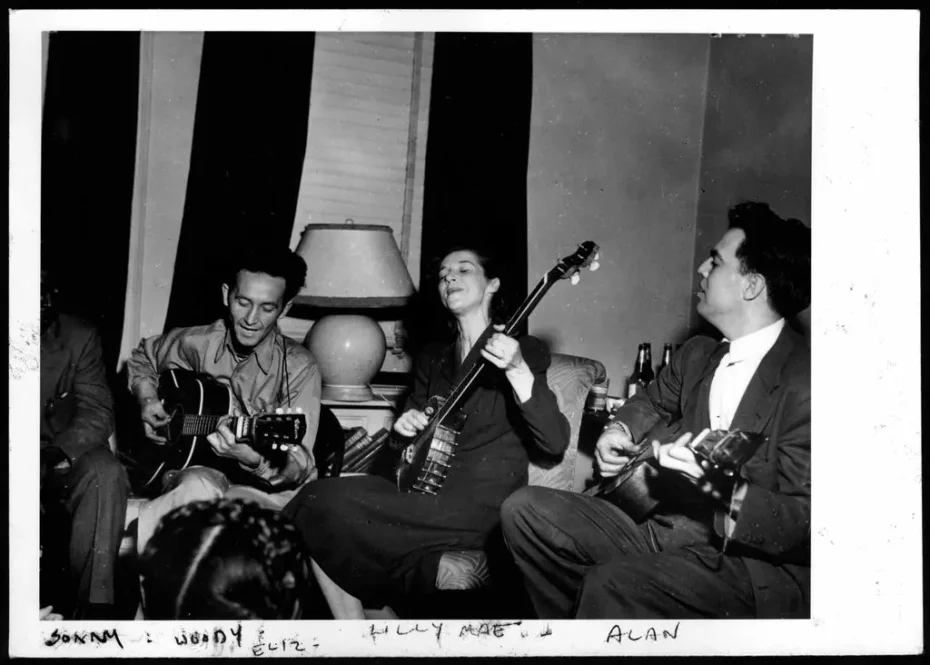

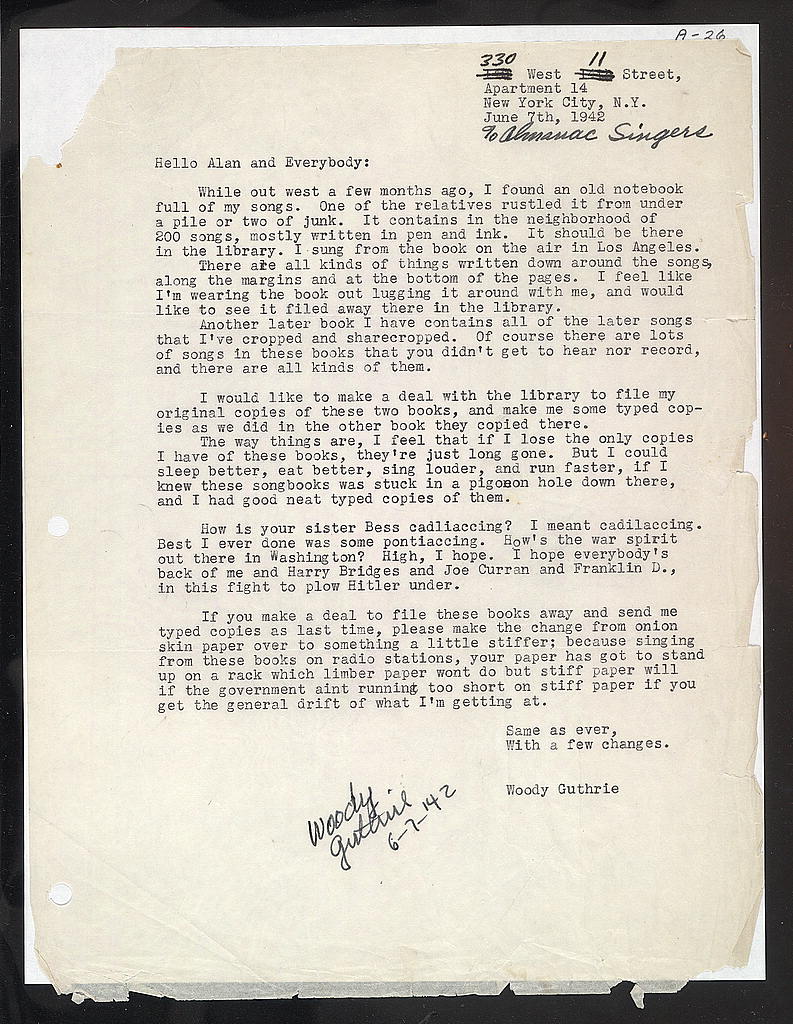

In 1938, Alan Lomax heard Jelly Roll Morton play at a club in Washington DC. What resulted was hours of interviews and music for the Library of Congress. Morton had been one of the first true pioneers of jazz in New Orleans. Lomax, realising the cultural importance of this, set out to gather as much information as he could from someone who had been at the vanguard of such an important cultural movement. In 1940, Lomax would record one of the most significant folk artists to come out of the United States, Woody Guthrie, who had a vast knowledge of traditional music, from cowboy ballads to mining songs.

Guthrie had traveled around America in the box cars of freight trains during the Great Depression and documented the injustices he’d witnessed in song. A socialist and antifascist, Guthrie had taken old folk melodies he’d heard and written protest songs around this structure. Lomax would be the first to record Guthrie. They would make hours of tape for the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress and it would become the defining record of that period of American folk history. In a correspondence between the two Guthrie wrote.

‘A folk song is what’s wrong and how to fix it, or it could be whose hungry and where their mouth is or whose out of work and where the job is or whose broke and where the money is or whose carrying a gun and where the peace is — that’s folk lore and folks made it up because they seen that the politicians couldn’t find nothing to fix or nobody to feed or give a job of work.’

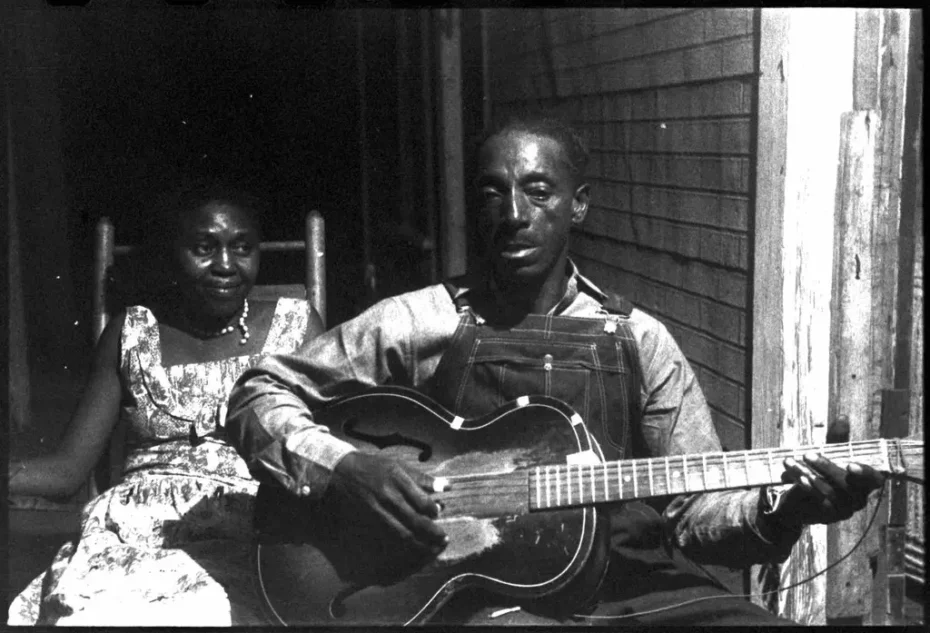

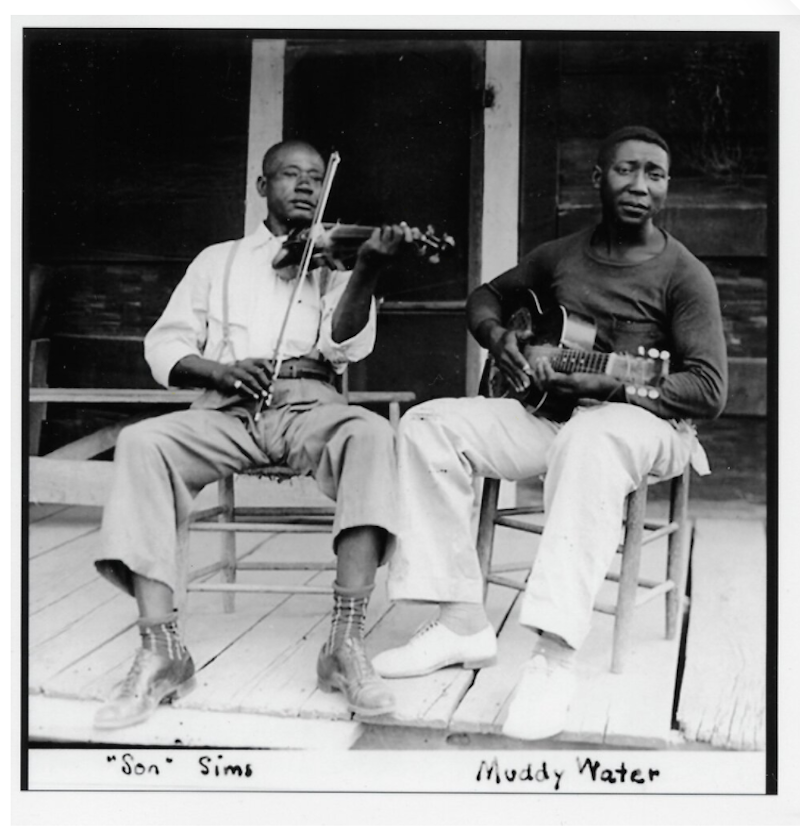

Traveling around the Deep South held its own perils for Lomax, to show an appreciation and interest in ‘race music’ during a time of fierce discrimination, segregation and violence towards African Americans was a dangerous undertaking. Lomax, undeterred continued his mission. In the Mississippi Delta in 1941, while searching for a local blues player he’d heard about (Robert Johnson), Lomax was informed they’d missed him. Johnson had died 3 years earlier, but he was referred to another local blues man, McKinley A. Morganfield – or as we now know him Muddy Waters.

After hearing two white men were looking for him, Waters initially thought he was in trouble. Upon meeting the Lomax’s and obliging to a recording a session, Waters would later say.

“I really heard myself for the first time. I’d never heard my voice. I used to sing; used to sing just how I felt, ’cause that’s the way we always sang in Mississippi,” Waters told one journalist. “But when Mr Lomax played me the record I thought, man, this boy can sing the blues.”

Muddy Waters

Waters would go on to become one of the most influential artists in America and England; a catalyst that ignited the British Blues scene and inspired artists from The Rolling Stones to Cream and Led Zeppelin. Lomax would continue to champion artists through his documenting, spreading the word about them on radio shows and securing recordings contracts with RCA for the likes of Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly.

“There’s a fundamental contradiction to the life and work of Alan Lomax,” notes NYT journalist Giovanni Russonello. “He encouraged Western audiences to appreciate rural and indigenous traditions as true art, on the same level as classical music. Meanwhile, he wanted to help those marginalized societies maintain distinct cultural identities, empowering them against the encroaching influence of mass media”.

Between 1940-41, he also produced a television series, Back Where I Came From; it was one of, if not the first integrated entertainment show to air in America. It featured songs, folk tales, and prose, and would be a soundboard for America’s unheard troubadours. The show was cancelled after 21 weeks.

During the McCarthy era communist witch hunts of the 1950s, a period in which anyone with slightly leftist leanings would be under close scrutiny from the FBI, Lomax probably quite wisely decamped to Europe. He settled in London and used it as a base to travel around Europe recording all the traditional music he could find.

In Spain, it would be the flamenco dancers and guitarists (his Spanish recordings would later go on to influence Miles Davis to record Sketches of Spain). On a barren island off the Scottish coastline, it was sea shanties and Celtic folk.

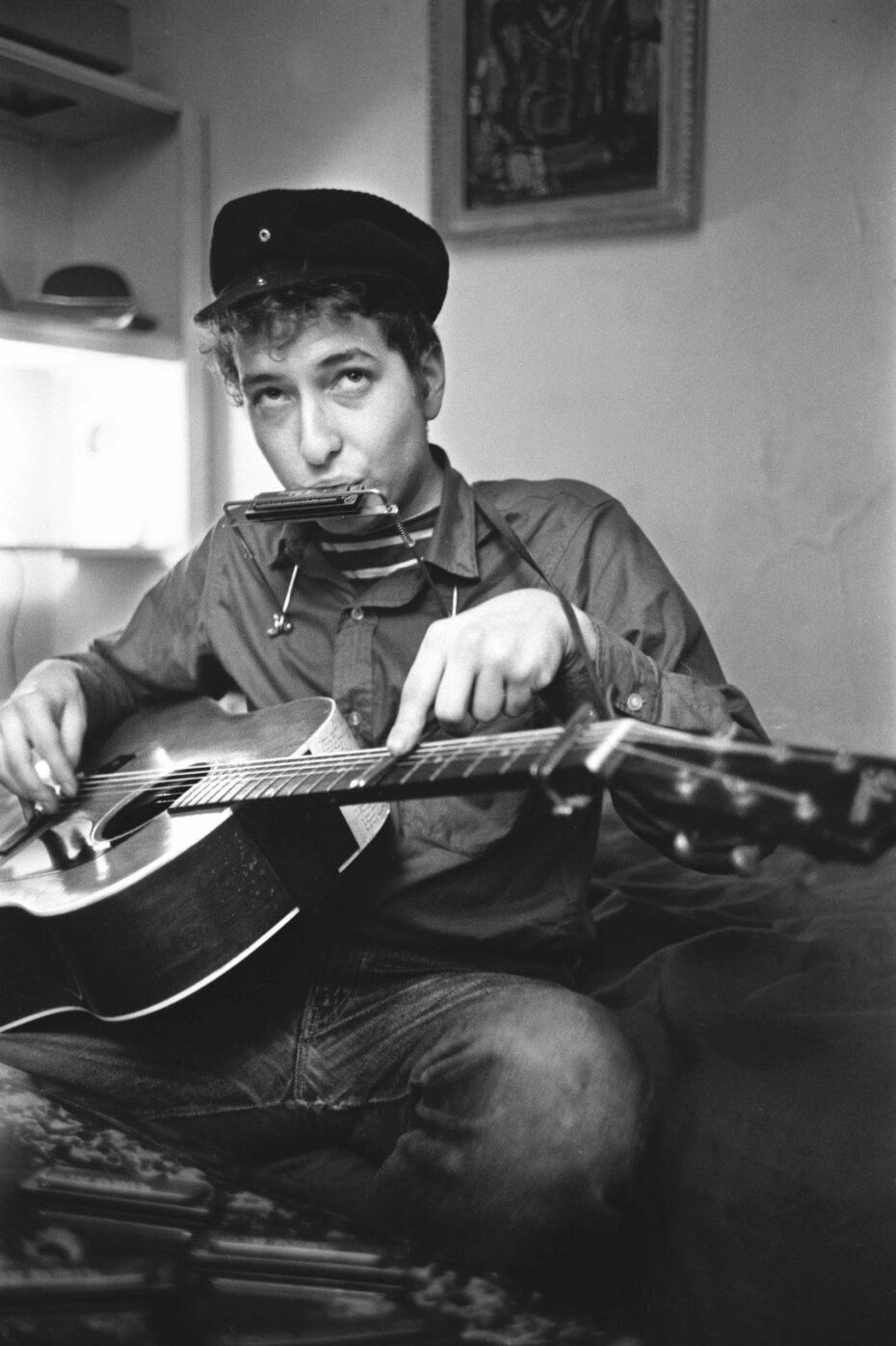

Alan worked for the BBC making The Song Hunter, a series where he traveled throughout Britain seeking out and recording old traditional music. After his return to America in the 1960s, he would be part of the folk revival that took hold in Greenwich Village, where a young and unknown Bob Dylan would visit Alan’s apartment looking for old recordings of his hero, Woody Guthrie.

When in 1977, NASA decided to send a 12-inch gold-plated copper disk into space containing sounds and images that could portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth, they asked Alan Lomax to help compile it. In addition to rock and roll, classical and Blues music, he added some Native American Navajo chanting, polyphonic vocal music from the Pygmies of Zaire, and shepherdess songs from Bulgaria. It seems Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, were lucky to be included at all.

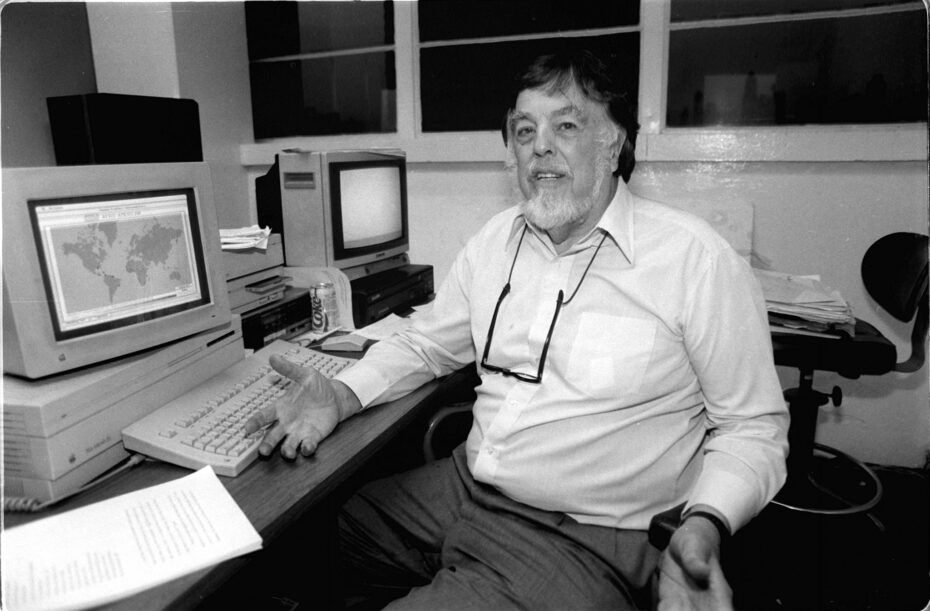

Alan Lomax would continue to promote what some people had labelled as ‘primitive’ music, and in the 1980s, he formed the Association for Cultural Equity, where his entire digital archive is now housed. He was responsible for thousands of hours of video and sound made by musicians and artists of traditional and cultural music that would not have been seen or heard if not for the will and desire of one man and a worn-out road map. He was a larger-than-life musical expeditionary, whose joy and passion for the base of creative expression saw him travel countless miles across continents and oceans, through cobbled streets and highways, to stone houses and debilitated shacks.

Lomax came to seek out the source, to listen and document a passion and obsession. He felt the wheels of industrial progression and the modern world starting to dissolve this overlooked art form, even from the beginning of his journey. The established gatekeepers of music had deemed the cowboy ballads and the shepherd songs unworthy of historical musical significance – mostly because of a lack of knowledge. Alan Lomax died in 2002 at age 86. Before he passed he was working on a project to bring all music and expression together from around the world. He labelled it the Global Jukebox.

‘The Global Jukebox is a powerful tool for learning that organizes and maps human expressive behavior with an illustrated geography of song, dance, and speech. It brings together results from a long-running cross-cultural research project that used techniques from ethnomusicology, dance notation, linguistics, and anthropology to describe, map, classify, and interpret orally transmitted performance traditions from all world regions. Its findings match and illuminate the known history of culture.’

Alan died before its completion, though his daughter and now-president of the Association for Cultural Equity would see his vision through to fruition.

We now label the sounds and songs that Lomax unearthed as “world music”, and Lomax himself as an ethnomusicologist. The hundreds of people he found on his travels maybe saw him as a brief distraction in their lives. He documented and labelled their contributions as a piece of everyone’s creative cultural identity. Because he realised their story was also our story, and in a part of them also lived a part of us.

‘We now have cultural machines so powerful that one singer can reach everybody in the world, and make all the other singers feel inferior because they’re not like them. Once that gets started, so much cash and so much power back them, that he becomes a monstrous invader from outer space, crushing the life out of all the other human possibilities. My life has been devoted to opposing that tendency.’

Alan Lomax’s massive music archive is online: and features 17,000 historic blues & folk recordings.