Every so often, an original is born; timeless, defying genre and completely of themself. Vali Myers, artist, dancer, environmentalist, bohemian and muse, was as original as they come, inspiring writers, artists and musicians from the streets of a post Second World War Paris to her bohemian coven in the wild canyons above Positano. Forming friendships with the avant-garde from Dali to Patti Smith, it seems that everyone who met Vali was captivated by the elfin-faced, flame-haired maverick known as the “witch of Positano”.

Born in Sydney, Australia in 1930 to a violinist mother and a father who was a marine wireless operator, Vali’s early upbringing, unlike the woman herself, was fairly unsensational. Determined to follow a career in dance, she soon figured out that rather than fight with her parents forever, she’d have to flee the nest. At only fourteen, Vali left home for Melbourne, grafting in factories to pay for her dance lessons. She quickly became the lead dancer in the Melbourne Modern Ballet Company, but feeling stifled once more by the place she called home, in 1949, at the age of nineteen, she fled again, much further this time, boarding a ship to Paris.

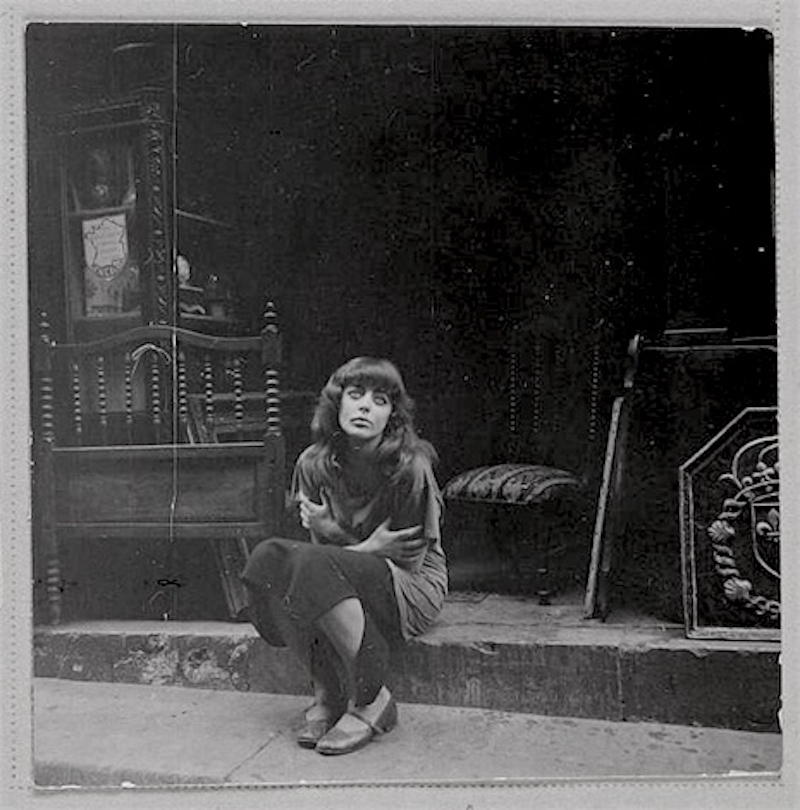

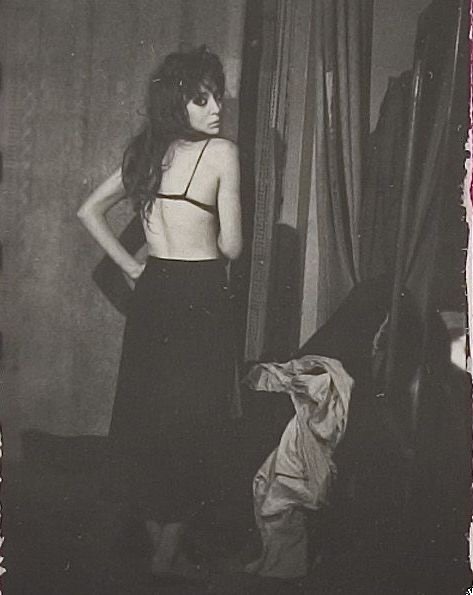

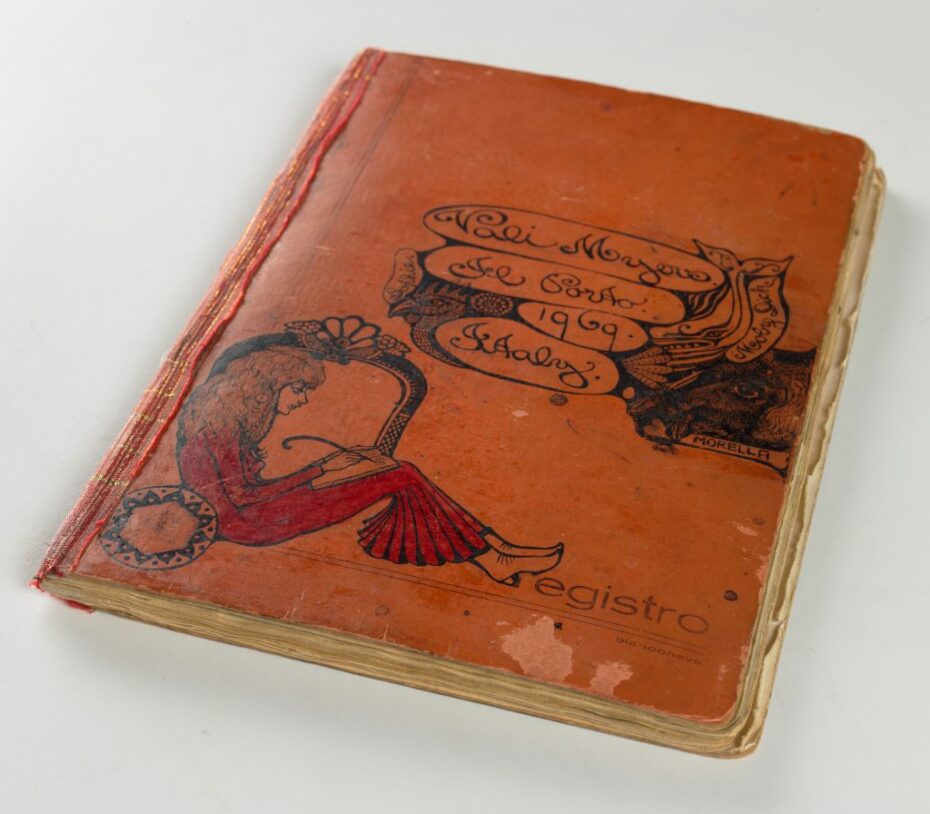

In 1950, Vali landed in an impoverished, post-war Paris. There were no jobs and she found herself struggling to survive with the city’s incoming wave of war refugees; finding a family amongst Romany people and displaced Jews from across Europe. She spent the next ten years on Paris’s streets, frequenting cafés of the Left Bank in the daytime and dancing for money in nightclubs, where she felt a connection with her new friends – misfits on the fringes of society – that lasted her entire life. All that she possessed were some clothes, a knife for protection and a sketchbook, small enough to carry around, both of which she took wherever she went.

It may sound vibrant and bohemian, but Vali said there was nothing romantic about it; they sat in cafés because they had nowhere else to go and dancing allowed her to eat. Discussing this period in an interview with Age Magazine just before her death, Vali said “It was a rough life. If you even picked up the stub of a cigarette, you shared it with everybody.”

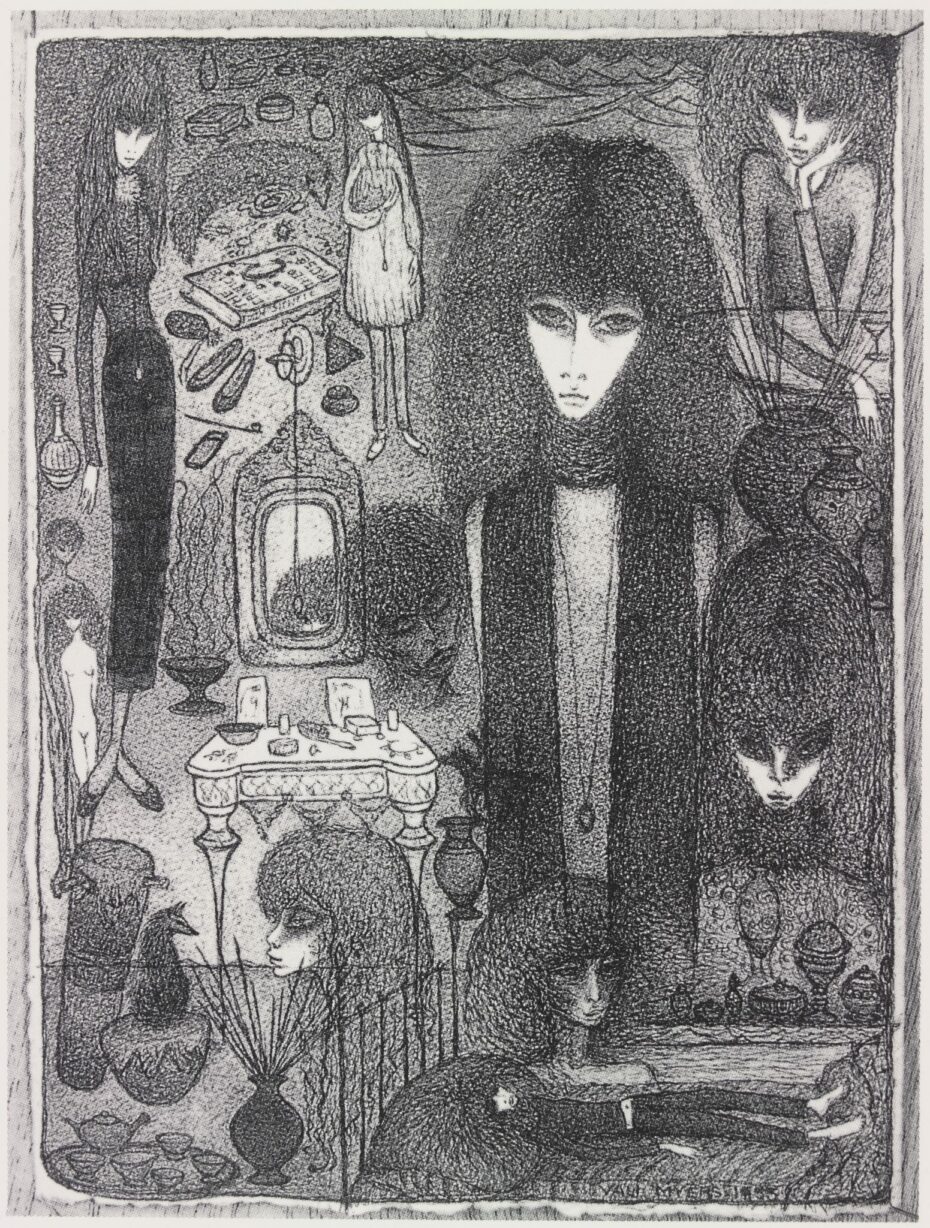

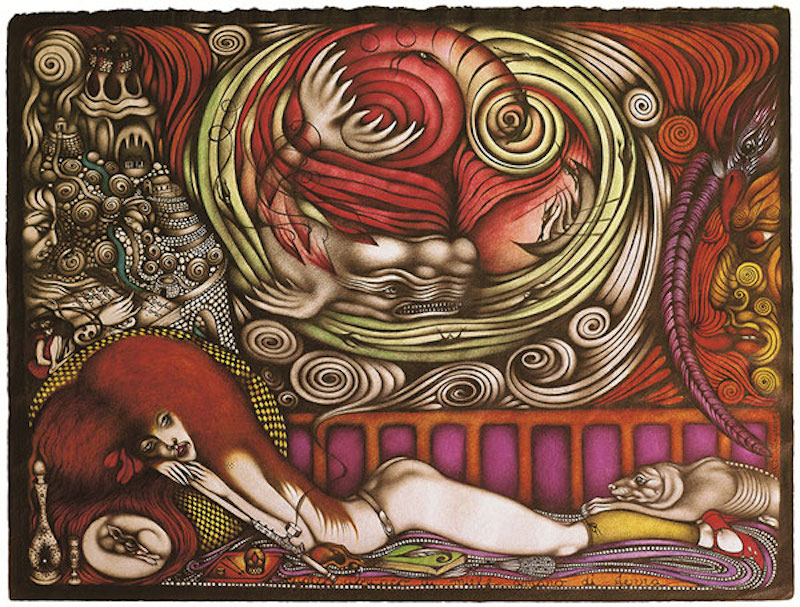

She poured her darkness into her art. Her works are a feast for the eyes, depicting flamboyant, psychedelic figures and animals, combined with mythological motifs. Centred upon the female (her women often resembling the artist), she explored primordial themes such as fertility, womanhood and the thin veil between nature, life and death.

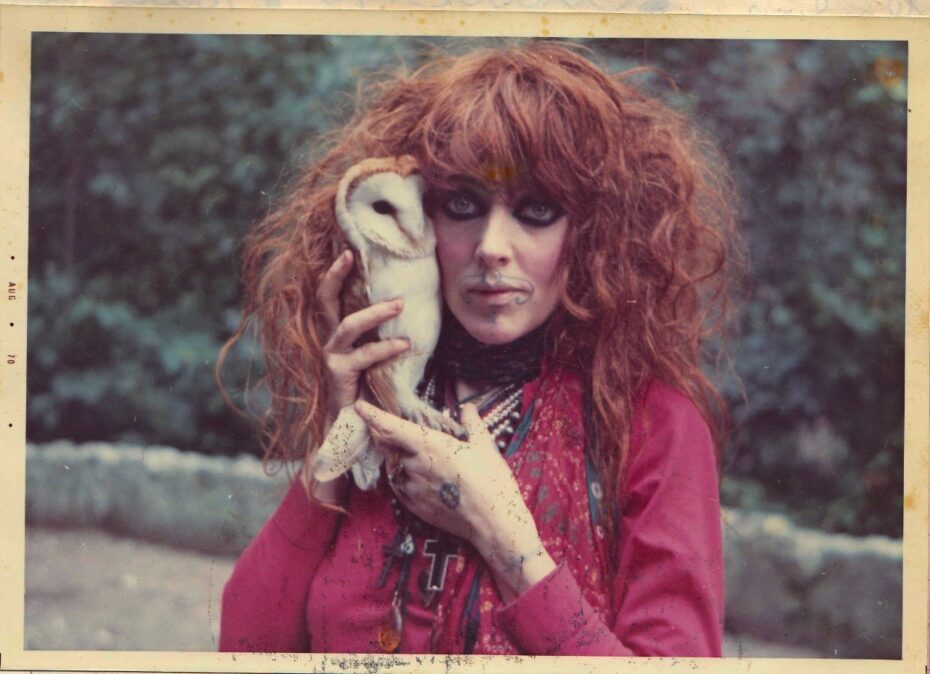

Contemporaries talk of how when she danced; everyone stopped to watch and she became known for her talent and her unconventional looks; bright red hair and eyes outlined in thick kohl, so different from everybody else. The Dutch photographer Ed Van Der Elsken was captivated and made her the subject of his Love on the Left Bank, a series of photographs capturing a fictional love story on the streets of Paris.

After multiple stints in jail for ‘vagabonding’, her visa expired and was denied renewal, so she left France in 1952. Hounded by the police and exiled into what she called her “walkabout” of France, Italy, Britain, Brussels and Austria, she met a young architect during her travels called Rudi Rappold in Vienna and they continued to wander Europe together. The only way for Vali to live legally in Europe however, was to marry, so she and Rudi did just that, ending their nomadic tour back in Paris, where they found kindred spirits amongst ex-pat writers, artists and bohemians who were bringing a new wave of cultural excitement to Paris after the war, such as Tennessee Williams and Jean Paul Sartre. She would smoke opium late at night with Jean Cocteau and continued a firm friendship with George Plimpton, founder of The Paris Review. It was Plimpton who first published a portfolio of Vali’s artwork in his magazine and went on to purchase almost everything she painted in the early days.

Tennessee Williams’ character Carol Cutrere in Orpheus Descending written in 1957 is clearly based on his friend Vali: “She is past thirty and, lacking in prettiness, she has an odd, fugitive beauty which is stressed, almost to the point of fantasy, by a style of make-up with which a dancer named Vali has lately made such an impression in the Bohemian centres of France and Italy, the face and lips powdered white and the eyes outlined and exaggerated with black pencil and the lids tinted blue.”

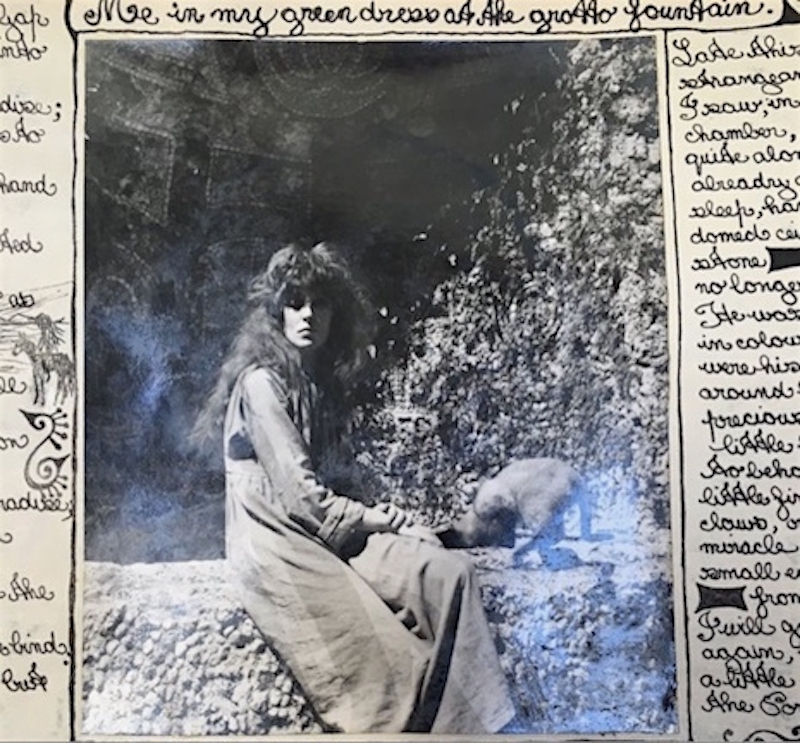

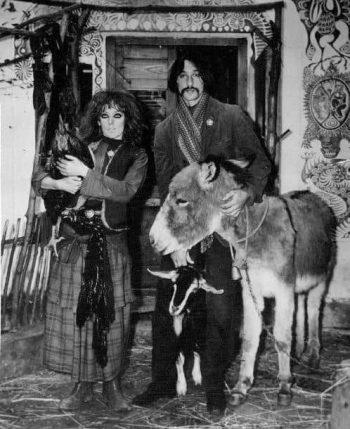

But there was a growing darkness inside his red-headed muse. Vali had become dangerously addicted to opium. Realising that opium was killing her, Vali left Paris for the final time in 1958, escaping with Rudi to Italy, where they ventured into the mountains above Positano and found an abandoned homestead; an 18th century domed pavilion built as a summer folly by a local aristocrat. Situated in a ravine at the edge of a sublime, thousand foot cliff that looks out on to the sea, accessible only by a challenging journey on foot (still to this day), Vali fell in love with the remote hideaway.

For years, she hibernated in the valley of Il Porto which became known as Vali’s Valley. She become one with the landscape and its creatures, many of which inevitably found their way into her compound, even her own bed, as well as her art. She and Rudi adopted a menagerie of animals from dozens of dogs, tortoises and ponies to her favourite, Foxy, an orphaned vixen that she raised as her own, letting her curl around her neck and sleep alongside her.

Vali was an environmental warrior before the term was even invented. When development threatened her beloved valley, she fought against the local authorities, eventually obtaining permission to preserve the area under the protection of the World Wildlife Fund.

Always ahead of her time, the 1960s swung in and suddenly Vali’s unconventional philosophy and way of life was the ambition of the psychedelic generation. By now in her thirties, Vali and her lifestyle became the stuff of legend after the American filmmakers Sheldon Rochlin and Flame Schon made a documentary film about her called The Witch of Positano, quickly becoming a cult classic in the States.

In the wake of the film’s notoriety, hippies and bohemian pilgrims starting arriving on her doorstep in Positano, including Marianne Faithful with her then boyfriend Mick Jagger.

“Marianne Faithful turned up one day with her boyfriend to see some of my work. I thought, who is this scrawny little guy, so I said to him, what is it you do Micky? How would I know who the bloody hell Mick Jagger was? – I wasn’t interested in Mick Jagger, I was always into Marianne. She was a real fighter.”

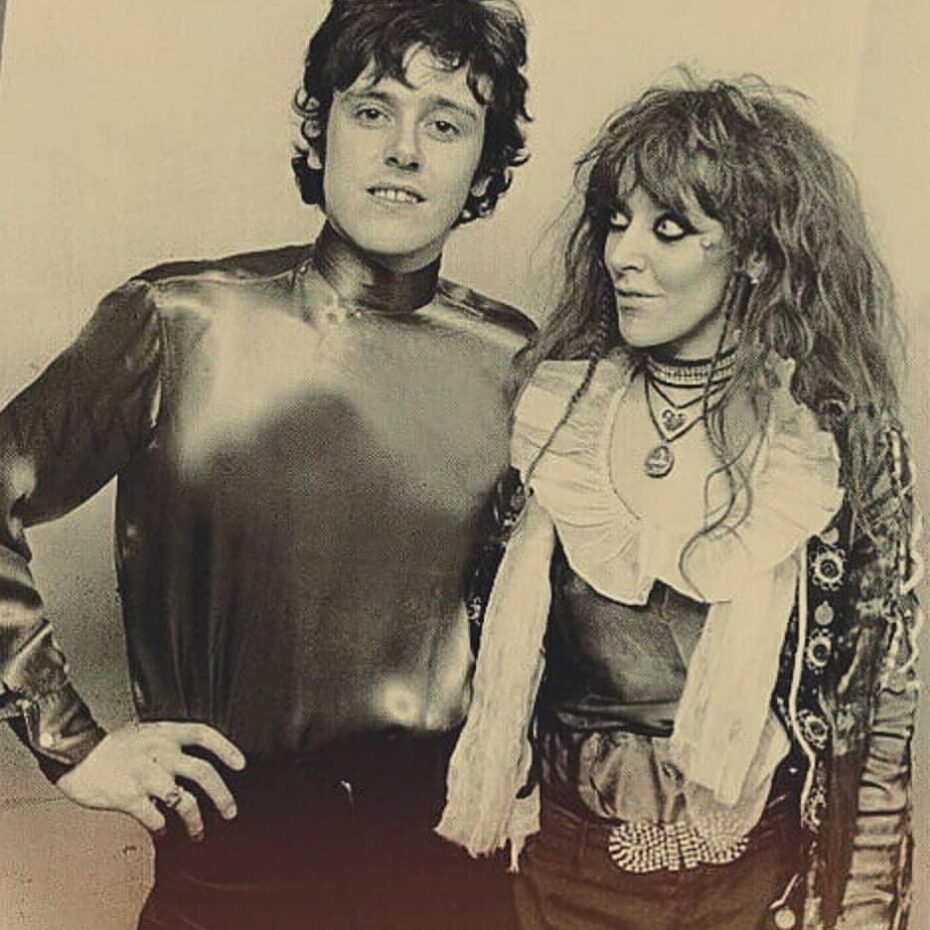

British folksinger Donovan, also visited Vali’s Italian homestead and later flew her to London in 1967 so she could dance on stage with him at the Royal Albert Hall to his song “Season of the Witch.” When asked what she wanted as a fee for her performance, Vali told Donavan, “one Nubian goat.”

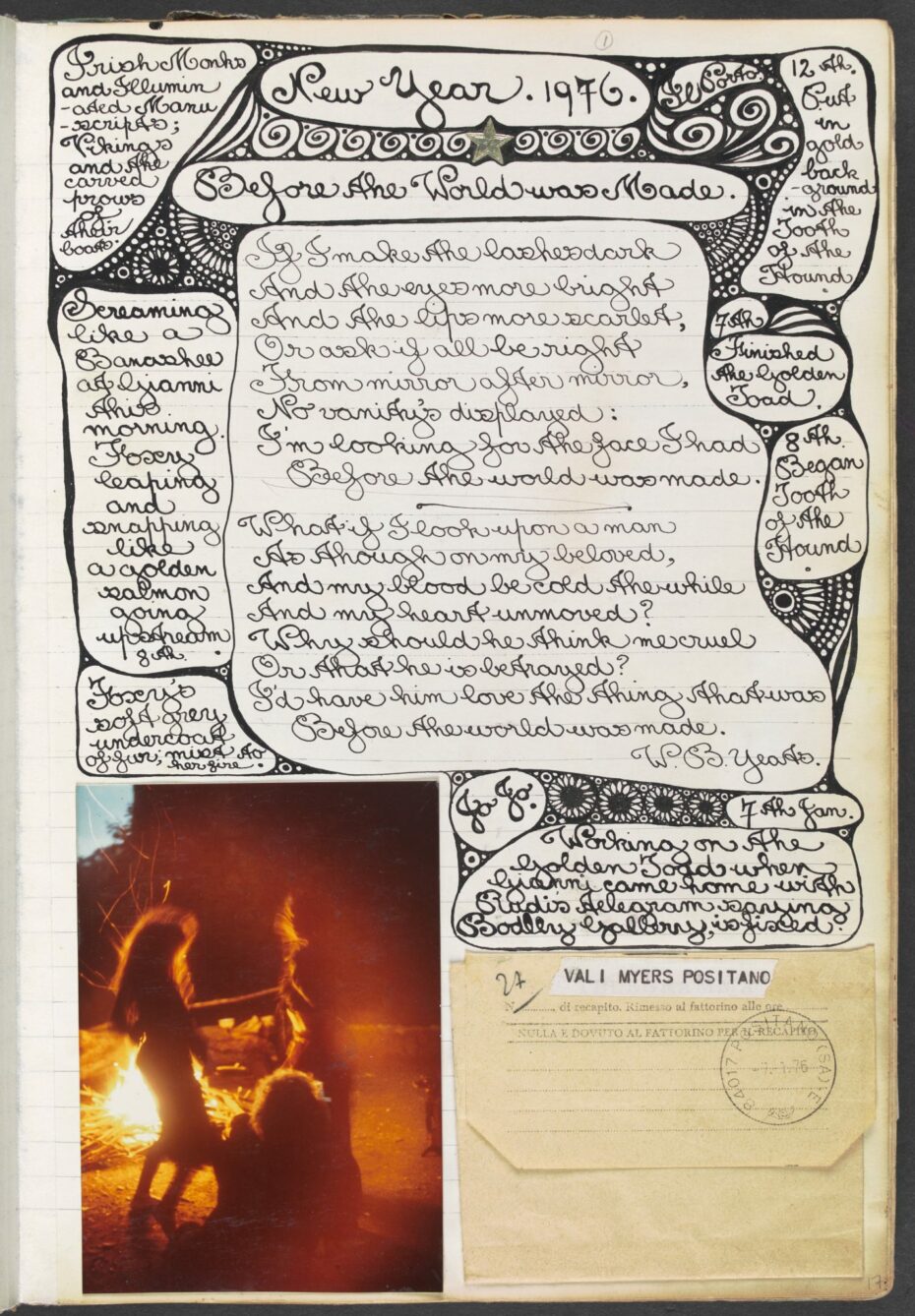

It is impossible to capture Vali’s essence in pictures alone. To see her dance or to watch her on film reveals a woman with a wild spirit, at times almost animal, at one with her landscape. In The Witch of Positano we see her tattooed, howling at the Moon, dancing with abandon and skipping effortlessly across impossibly steep crags with Foxy and the dogs, bare-footed and elemental (see the 5 minute and 7m20 mark of this Youtube upload).

In a 1963 diary entry she wrote:

“Let it all be animal, my life and death, hard and clean like that, anything but human…a lot I care, me with my red heart in the dark earth and my tattooed feet following the animal ways.”

By the 1970s, Vali was in need of money for her wildlife sanctuary and she travelled to New York to sell some of her paintings, moving into the infamous Chelsea Hotel, home to the bohemian elite.

“Every time I’d saved a bit of money I’d go back to the Chelsea”, she recalled in an interview with Age magazine in 2003. “I don’t think any other hotel would have had me. We’d have mad drinking sessions, where bottles would end up smashed against the wall.”

In 1971 … Vali Myers, with a live fox on her shoulder, entered the lobby of the Chelsea Hotel, in New York, where I lived with Robert Mapplethorpe. She was then a tattooist, among other things. Recognizing the girl in the rain-pitted mirror, I gathered my courage and asked her to tattoo a lightning bolt on my knee, and she consented. And so she touched me first as an image and then as a human being, and I am happily branded for life. I still have my tattoo, and those images of an unobtainable but brutally familiar nightlife. They have always been with me, for they are, like Vali herself, unforgettable.

– Patti Smith for Vanity Fair

Vali found herself at the centre of a creative movement once again, hanging out with the likes of Patti Smith (whose knee she famously tattooed), Andy Warhol and Salvador Dali. It was fellow resident Warhol who suggested she sell reprints of her work as creating just one original work could take Vali months or years to create. Dali’s recommendation to exhibit her work led to her first show in Holland in 1972, and in 1975 her old Paris friend George Plimpton published a second portfolio of her work in The Paris Review.

Nonmaterialistic as ever, almost everything she earned she pumped back into Il Porto. Back in Italy, she had found a new companion, Italian artist and poet Gianni Menichetti, who had first met Vali delivering food to her pavilion, and would later become her longtime friend, lover and co-guardian of her sanctuary in the wild green valley.

In 1980, a book of her work was published with beautifully created captions in her unique calligraphy, highly sought after today in the art market. The eighties culminated in Australian filmmaker Ruth Cullen producing The Tightrope Dancer, a film contrasting Vali’s frenetic life in New York with her hermetic one in Il Porto.

After an absence of 43 years, in 1993, Vali finally returned to Melbourne where she semi-settled, continuing trips back and forth to Positano. Falling in love with the city she had abandoned in her youth, she exhibited her work and in 1995 set up a much treasured studio Gallery in the Nicholas Building.

Diagnosed with stomach cancer in 2002, she was interviewed shortly before her death in Melbourne. Her trademark red hair and makeup were in tact, her facial tattoos a permanent stamp of her character:

“I’ve never made any plans. I don’t understand why people want to get some kind of insurance on life. Nothing lasts forever. I’m disintegrating and I’ve never felt better.”

Vali’s spirit was still very much alive. She continues to fascinate artists such as Florence Welch who named her as inspiration for her album How Big How Blue How Beautiful.

Despite her kind and gentle heart to all who entered her orbit, she was a woman fiercely true to herself. “Why should I explain myself to people who don’t understand? I am what I am, there it is.” She gave us all a lesson in true bohemianism.

According to her wishes, her ashes were scattered in the ocean on Friday 13th, February 2003 and the Vali Myers Trust, a non-profit organisation, was set up in Melbourne to safeguard her work and make it accessible to all. She had made her last visit to Il Porto in 2003, which is still protected by the WWF and her work there continues through her companion Gianni Menichetti, who wrote the biography Vali Myers – A Memoir and continues to tend to her menagerie. If you’re in Positano and curious to take a break from la dolce vita in favour of a pilgrimage to the remote site of Vali’s hideaway, a donation to the animal sanctuary is recommended and your journey starts with contacting Gianni.