Venturing down an unassuming gravel road grown over with grass in rural Marion County, Georgia, you’re met by a huge pair of piercing blue eyes. Look around, and you’re met by many more sets of eyes staring out from intense faces emblazoned with vivid reds, greens and yellows, adorned in geometric patterns and spiritual symbols. It feels as though the whole place is watching you and waiting. This is Pasaquan, a seven-acre visionary art complex, holy site for a one-man religion and the life’s work of Eddie Owens Martin, a Southern saint of his own styling.

“You’re gon’ be the start of somethin’ new, and you’ll call yourself Saint EOM, and you’ll be a Pasaquoyan—the first one in the world.”

Martin was born on the Fourth of July 1908 in Glen Alta, Georgia, the son of sharecroppers clawing a hardscrabble living out of the Southern backwoods. Early life was hard for Martin, even beyond the poverty. His father was a drunk and a gambler, a violent and abusive man. As a kid with a creative spirit and a flair for the dramatic, Martin felt perpetually out of place in this tiny town, and one night when he was 12 years old, he wrapped himself up in a tasseled piano shawl (the piano itself had been repossessed due to his father’s gambling debts), raised his hands to the full moon and prayed that God would make him different from anyone else in the world.

At 14, Martin decided he’d had enough of Georgia and set off making his way up the Eastern seaboard as a sex worker before landing in New York City. Here, with the Roaring 20s in full swing, Martin found himself surrounded by a seething creative underworld populated with drag queens, artists, performers, drug dealers, hustlers and gamblers.

Martin told his biographer Tom Patterson that he went to New York, “with my eyes wide open. I had thrown myself on the mercy of this world, but I knew I had to make a buck to survive. And in a big city like New York, if you’re a nice-lookin’ boy or girl, you can survive.” He ran an underground poker den and served down-home Southern chili and fried chicken with ice-cold beer on the side. He sold weed, performed in drag under the name “the Tattooed Countess” and worked the gay nightclub scene as both a waiter and a prostitute. But he managed to find the most success as a fortune teller reading tea leaves at the Wishing Cup tearoom, where patrons lined up time and again to hear Martin’s insights into their lives. “You had to be psychic just to survive in that street-hustlin’ scene, man!” Martin said to Patterson. “You had to have eyes in the back of your head!”

While these flamboyant pursuits helped him earn a living, Martin’s real interests were in the artistic realm. He spent hours at the New York Public Library and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, devouring works on the occult and the supernatural as well as non-Western religions, studying countless examples of Native American, African and Pre-Columbian South and Central American Art. He was particularly inspired by the works of James Churchward, who theorized that a lost Pacific continent called Mu gave rise to an ancient, technologically advanced civilization stemming directly from the Garden of Eden and eventually creating colonies that became India, Persia, Egypt, Babylon and the Mayan civilization. While Churchward’s works have been thoroughly debunked as pseudoscience, Martin found something in them that spoke to his desire for society to return to a mythical “natural state”, where all races and religions lived in harmony.

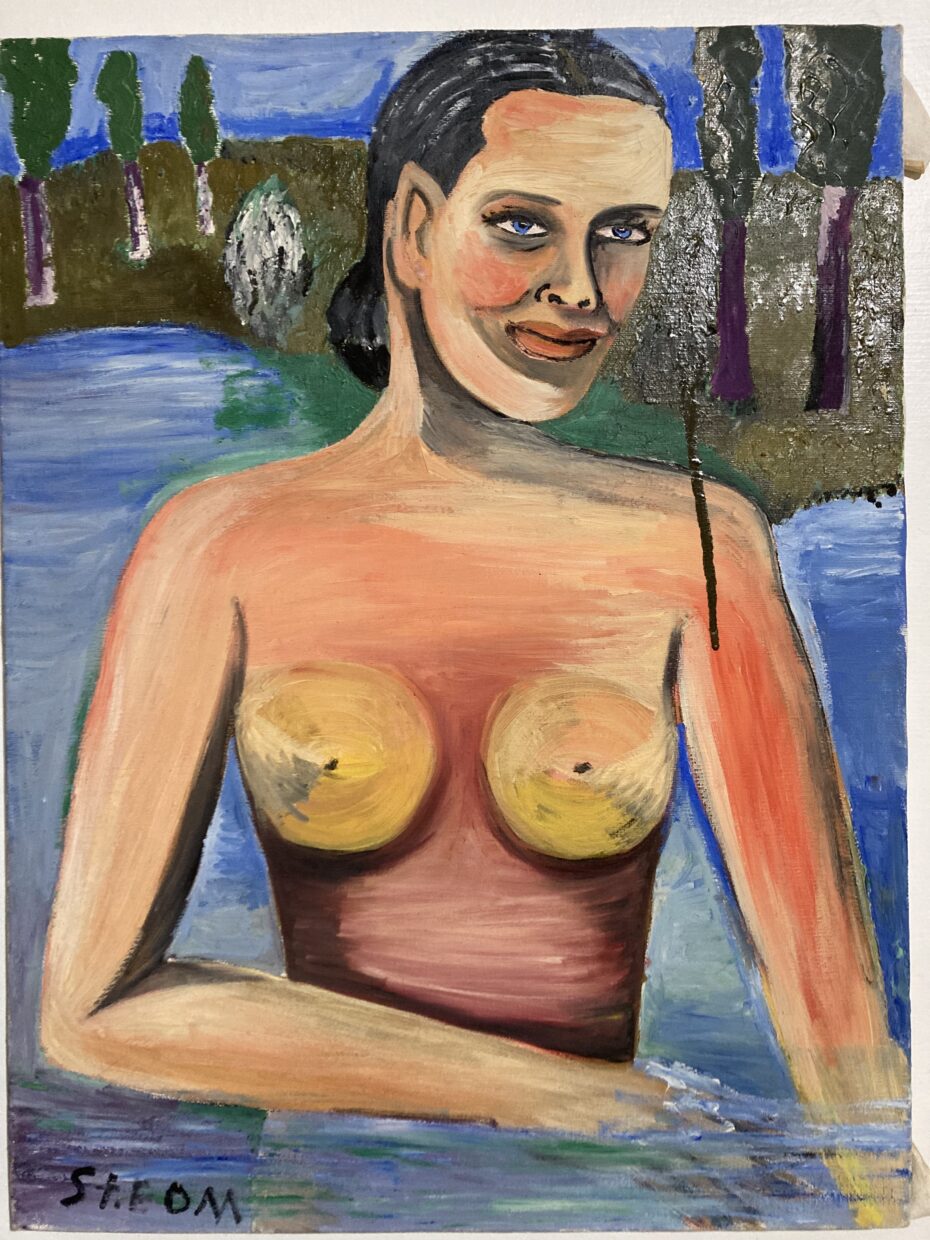

When he wasn’t hustling for a buck, Martin threw himself furiously into painting. Many of his early sketches depict high fantasy fashions with nods to historical Egyptian, Thai and Mayan clothing and a heavy dose of science fiction, all wrapped up in an androgynous style and surrounded by faces – always faces. Martin said he was so hard-up for cash in those days that he couldn’t afford canvas or paints. Instead he used whatever discarded cardboard he found on the street and fashioned frames out of scraps of wood he carved himself.

Around 1935, Martin fell ill both mentally and physically. He couldn’t eat and said he felt as though he was coughing up all the evil and confusion inside himself from years of not being himself. At the point when he expected to die, he saw a vision. “My spirit seemed to leave my body, and I encountered this vision of a great big man sittin’ there like some kinda god, with arms big around as watermelons. And his hair was long and went straight up from the top of his head, and his beard was parted in the middle and goin’ straight up the sides of his face. And he said to me, ‘If you can go back into the world and follow my spirit, then you can go, but if you can’t follow my spirit, then this is the end of the road for you.’”

Martin did go back into the world and back into his art. But that wasn’t the last of his mysterious visions. A few months later, as he was sketching Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia from a photo in the New York Times, he saw the image of another man’s face with long hair swept straight up. “And all of a sudden this voice spoke to me and told me, ‘You’re gon’ be the start of somethin’ new, and you’ll call yourself Saint EOM, and you’ll be a Pasaquoyan—the first one in the world.’” He claimed to later discover that “pasa” means “pass” in Spanish (which is true) and that “quoyan” is ‘some kinda Oriental word that means the coming of a great event in the future” (that part could not be verified).

The newly minted St. EOM (pronounced ohm) threw himself into developing the tenets of this new religion of Pasaquoyanism. Central among these was never cutting his hair because it is “the antenna to the spirit world.” He believed the citizens of Mu and Atlantis wore their hair and beards long, in the image of the “complete, natural man” and that they were guardians of rituals that modern man had forgotten due to greed and militarism. So St. EOM grew out his beard and tied his long hair into a top knot topped with various headdresses of his own design. Even among his community of New York misfits, Martin was becoming strange and unsettling, and old acquaintances began to cross the street to avoid him.

The more isolated he became from the community, the more obsessively he turned to his art, staying up into the early hours painting in a haze of marijuana smoke as psychedelic images of faces with hair standing straight up emerged from his makeshift canvases. St. EOM exhibited his work at street festivals and tried to break into the gallery scene but even he recognised his work was too bizarre for the traditional art world.

In 1957, St. EOM inherited his mother’s farmhouse and moved back to Buena Vista, Georgia. Much as he had in New York, he continued to make ends meet as a fortune teller. Though he never advertised his services, people sometimes drove hours to see him and then waited hours more in line once they arrived. “They’re all puzzled and in a whirl,” Martin said of his clients. “And I just break it all down into a few words of common sense. What I am, really, is a poor man’s psychiatrist.”

Psychic readings paid the bills, but St. EOM knew he needed more. With no plan and no building skills, Martin began putting up walls around the property, sculpting faces in the wet cement. He hired local day laborers to help, but they had just as little knowledge of construction as Martin did. The entire enterprise was trial and error, and parts of it fell apart during construction. But St. EOM knew he had a “good spirit” to guide him toward the designs and symbols that represented “the universe and its forces and the great powers that hold all of this planet here together.” There is likely not a straight line on the property as Martin and his helpers levelled everything by eye. With the perimeter wall constructed, Martin finally felt he had “shut out the world” and could fully devote himself to his artistic and spiritual utopia. “I built this place to have somethin’ to identify with, ‘cause there’s nothin’ I see in this society that I identify with or desire to emulate.”

In 1967, he took a solo journey to Mexico and Guatemala. Inspired by the vibrant colours he encountered on this trip and particularly struck by Diego Rivera’s mural “Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central,” Martin returned to Pasaquan and proceeded to add entirely new dimensions to his concrete works. He built temples, totems, pagodas and a ritual dance platform, every inch vividly adorned. Today we would rightfully say that Martin appropriated much of his work from cultures to which he did not belong. But it is also true that St. EOM genuinely believed he was presenting these works in an appreciative way.

Even former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, also a Georgia native, visited the site to meet St. EOM. And naturally, Martin claimed he read the President’s fortune, though Carter later said he didn’t remember.

As he aged, he became increasingly disenchanted with the world ane lamented that only one in a thousand of his visitors actually came to see his art. He employed two German shepherd guard dogs trained to attack anyone who came with “bad vibrations.” Rumours swirled that he also trained rattlesnakes to respond to his call. The demands and harsh realities from which his clients sought relief dragged him down even further. Though St. EOM felt ostracized by modern society, neighbours remembered the eccentric artist fondly, recalling his presence at local festivals for Halloween and Independence Day, always clad in his colourful ceremonial garb. But as the years passed, Martin sought solitude above all.

Though St. EOM once believed his Pasaquoyan faith would allow him to live forever, an aging physical body weighed him down. Heart and kidney problems landed him in the hospital frequently, and he hated the thought of losing his independence. He died by suicide in 1986, but his tombstone lists no date of death in deference to Martin’s belief in his own immortality. The self-styled saint was buried in a Cameroonian chieftain’s robe he had recently acquired.

Martin left Pasaquan in the care of the local historical society, which formed an off-shoot group called the Pasaquan Preservation Society to preserve the site. Pasaquan was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2008, but the complex was plagued with crumbling masonry, peeling paint and structural issues. In 2014, the Society reached out to the Kohler Foundation (yes, of toilet-making fame), a philanthropic organization dedicated to art preservation. Kohler took on the project, bringing in teams of international conservation experts, but also working closely with the local community to ensure first-hand knowledge of the site informed the preservation project. After the two-year, multimillion dollar restoration was completed, Kohler gifted Pasaquan to Columbus State University. Arts students and faculty from Columbus State contributed to the preservation efforts and continue to aid the ongoing upkeep needed.

St. EOM felt defeated in his lifetime because he never found financial success with his art and feared no one could understand his message. Yet today visitors come to Pasaquan entirely for its artistic importance, and the artist-saint’s work continues to inspire the works of others; musicians, actors, spiritualists and searchers are all drawn to the site (2.5 hours south of Atlanta) which hosts art exhibits, concerts and performances. Charles Fowler, Pasaquan’s caretaker, said that in particular many members of the LGBTQ community who visit the site fall in love with the place and feel a strong connection to Martin, who was unrelentingly himself in a time and place where it could be dangerous to do so.