Of the six original Universal Monsters, none is so ubiquitous and iconic as the Creature from the Black Lagoon. The film, released in 1954, still screens regularly at theatres dedicated to classic cinema. What few knew until recently however, is that the credit for the Creature’s iconic design was cruelly stolen from one of the industry’s earlier female animators, Millicent Patrick. Thanks to a recent biography, The Lady from the Black Lagoon, we can now know all about the Beauty who Created the Beast.

Patrick had an an unusual upbringing, growing up at Hearst Castle where her father worked as the superintendent of construction on the estate. In her early twenties, she was in Los Angeles trying her hand at acting and throughout her life appeared over twenty films, mostly uncredited. She was a woman of many talents; actress, artist, gifted concert pianist; but she also a private woman who shied away from the limelight. Preferring to stay behind the scenes, she began work at Walt Disney Studios in 1939 for a team that became known amongst employees as the “Ink and Paint Girls.” By 1940, Millicent proved so skilled that she moved to the Animation and Effects department, where she became one of the first female animators at Disney. You know her work even if you don’t think you do – seen in several sequences in the classic film, Fantasia, including her creation of the devilish creature, Chernabog, from the finale. She also contributed to Dumbo as well as several other animated features and was even profiled for her work in Glamour magazine at the time.

Patrick’s next posting was at Universal Studios, where she’s cited as being the first woman to work in a special effects and makeup department. Not just at Universal Studios: the first woman to work in a special effects and makeup department in the entire industry. Under the guidance of Bud Westmore, Patrick and the makeup team created such memorable monsters as the globs in It Came From Outer Space and Mr. Hyde in Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Keep in mind, this was all before computer generated animation, which involved sculpting real costumes. To produce the body costumes for the Gill-Man, they made a cast of the actor, diver and Navy veteran, Ricou Browning. From those casts, the team produced custom, formfitting latex leotards, and then glued on the fins and foam rubber parts of the Gill-Man. Next, the team sculped the heads, hands, and feet in clay before casting them in plaster. There are a few fun facts about these elements: first, the experimental heads were sculpted over a bust of actress Ann Sheridan because hers was the only life mask the makeup department had that extended through the neck – and that was important because the Gill Man has gills. You can even see them expand and contract on screen, which they achieved by use of an expandable bladder that technicians operated off-camera.

According to the costume’s sculptor, Chris Mueller, it was indeed Patrick who drew the original sketches for the Gill-man. He stated that while Bud Westmore is the only makeup artist credited on the movie, he had nothing much to do with the project. Writer Vincent Di Fate notes that the costume took around six to eight months to create and cost the studio somewhere between $12,000 and $18,000 “(in 1953 dollars — roughly what was then the equivalent in cost of a fairly spacious home). He continues to say that “whatever the true numbers may have been, it also took great talent and imagination to develop this indelible cinematic icon.” Clearly, this costume, from design to execution, was no small accomplishment.

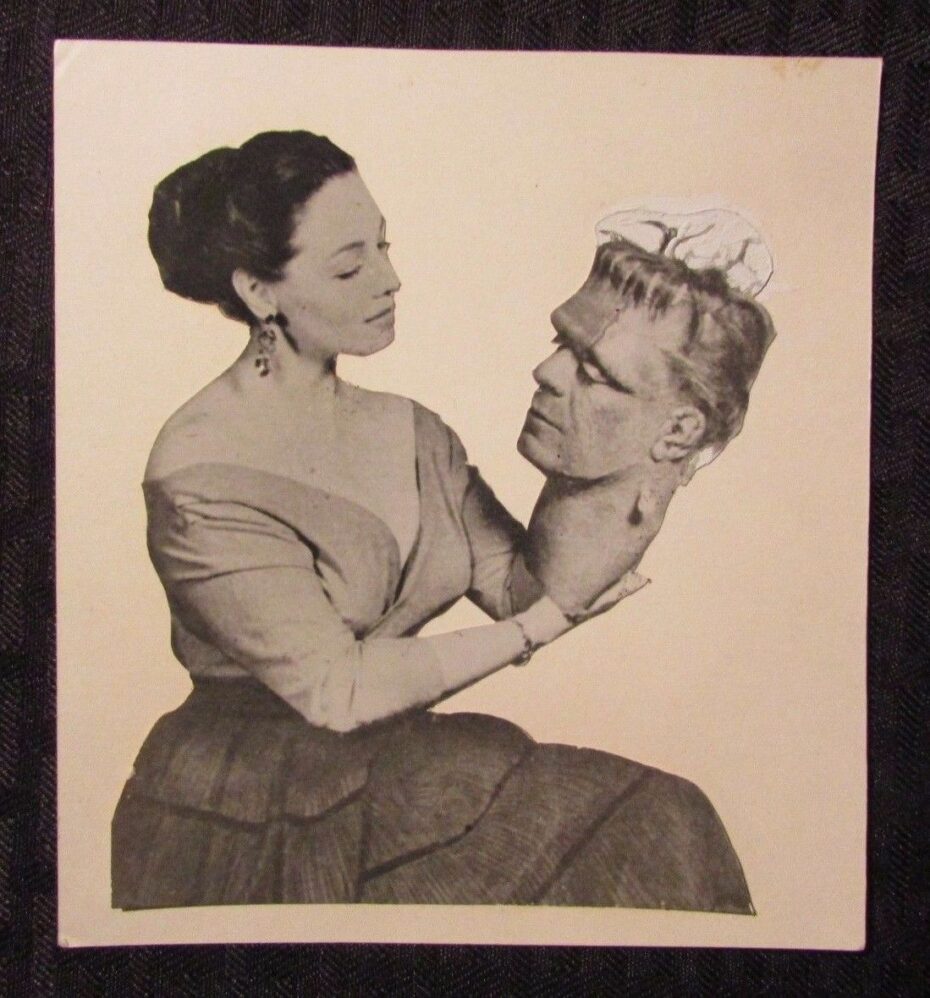

Seeing an opportunity, Universal initially sent Patrick on a press campaign to promote the film and talk about the creation of the creature. They called that tour “The Beauty Who Created the Beast.” It had a nice ring to it. Bud Westmore however, the head of the Universal makeup department, wasn’t having it. He didn’t want to cite Patrick as the creator because, according to him, all she did was turn his sketches into a costume. He changed the tour’s title to “The Beauty Who Lives With the Beasts.”

While on the renamed press campaign, in an interview with The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Patrick said: “I spent six weeks with the Gill-man. He changed his shape three times before he was able to win the approval of the executives who always have the last word on Hollywood monsters.”

Bud Westmore read the article and his jealousy boiled over. He barged into advertising and publicity executive Clark Ramsay’s office, where he “let it be known in a general way that he is not going to use [Patrick] as a sketch artist anymore,” Ramsay wrote in a memo dated March 1, 1954. When Patrick returned from the tour to Los Angeles, she was informed that she was no longer employed by Universal Studios. Clark Ramsay, however, noted in the same memo mentioned above, “I think we all agree that Westmore is being a little childish over the entire matter.”

Universal’s science fiction films boomed during the ’50s, but because of Westmore’s tirade, Millicent Patrick’s contributions to the other films have been forgotten. In addition to the Gill-man, her ghoulish creations are believed to have included the Xenomorph for It Came from Outer Space (1953), the Metaluna mutant for This Island Earth (1954), the masks on Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1953) and The Mole People (1956).

“The Screen Actors Guild currently lists her among the missing,” writes Vincent Di Fate, “and no definitive record of her life, her death, or her whereabouts seems to exist beyond the early 1980s.”

Millicent Patrick may have ended her monster-making career in obscurity, but her Gill-man went on to become a horror movie icon. And now, Patrick has her own biography, written by adoring fan, historian, and writer Mallory O’Meara in 2019, The Lady From the Black Lagoon. The biography is highly recommended reading for any artists and creators out there struggling to find their place in an industry that to this day, has difficult giving credit to the people that make the entertain business tick.