North America has its own Chernobyl(s). There are gold rush ghost towns, and then there are uranium ghosting towns; settlements which grew out of the “uranium fever” of the first part of the 20th century and testaments to an era when fear of nuclear war led to an unprecedented rush for a previously low-value mineral. But what really became of these mines and the mining towns that catered for them?

We’ll begin our tour in Jeffrey City in Wyoming, which had once been home to a single homesteading couple who settled there in 1931. For a long time they were the only residents until a uranium mine opened there in 1957 and turned it into a boomtown. The population grew quickly, reaching 4,500 in 1979, by which time it had a bustling main street, hotels, a high school and library, churches, even an Olympic sized swimming pool. But everything changed when the uranium market collapsed and the mine closed in 1982. The population was down 95% by 1985 and today its an American ghost town in every sense of the word, with a last recorded population (as of 2010) of 58.

Forgotten places like this can be found across North America. Some are fenced off with radioactive warning signs (these holes in the ground are billowing radon gas) but most of them are just abandoned. Unassuming campers and hikers are often known to explore the caves where pieces of uranium ore are lying around, a dark memory of a boom motivated by fear of the worst.

It’s estimated that some 10,000 people moved into settlements to meet the demand for uranium nearing the end of the Second World War. The radioactive chemical was the key to the early nuclear bombs that changed the course of the conflict, particularly in the Pacific. “Little Boy,” the first of these devices, was dropped over Hiroshima in 1945, causing tens of thousands of deaths.

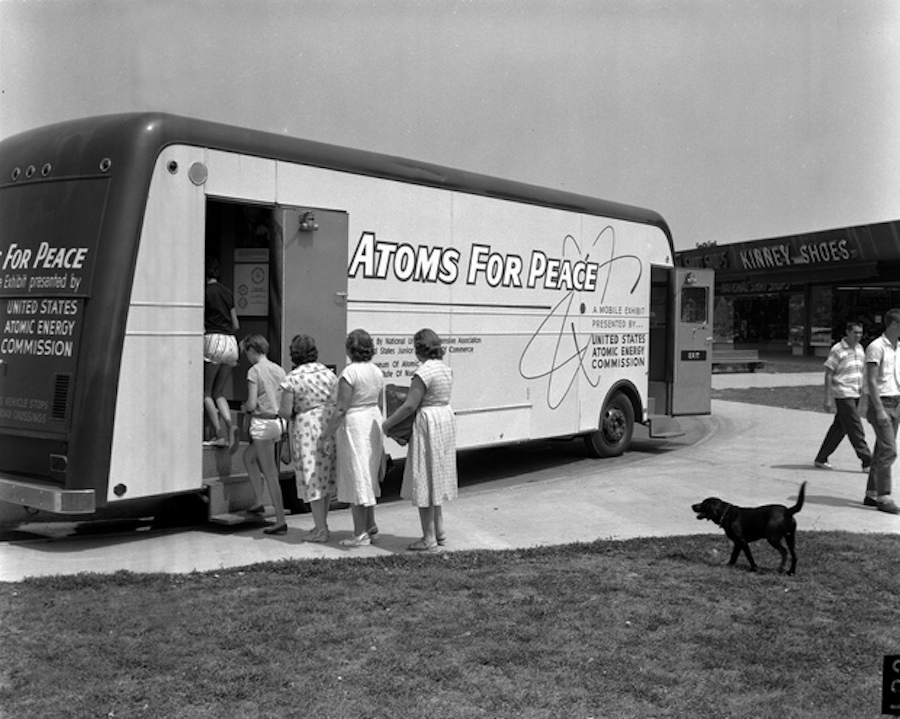

The early days of the Cold War motivated further interest in developing these weapons of war, pushed by the Automic Energy Commission (AEC). Uranium, the only organically occurring element that can sustain a chain reaction, was also the centre of research for powering nuclear power plants and nuclear submarines.

Like any “rush,” that for uranium had many losers and only a few winners. Prospectors each had their own theory of where they would hit “yellow gold,” either keeping the mine for themselves or a major company. The raw ore would then be converted into yellowcake. One of those who struck big was Charlie Steen, a prospector who became known as the “King of Uranium.” An oil geologist by training, Steen had a leg up in the race but also struggled for many years, living in harsh conditions with his young family (three young boys and an expectant wife) in a trailer on his claim near Cisco, Utah before finally hitting it big.

Steen couldn’t afford the standard radiation-detecting equipment and relied on a secondhand diamond drill rig. But he had a strong theory: he believed that like oil, uranium deposits would gather in structures with an anticlinal (arch-like) shape. This was considered so unlikely it was called “Steen’s Folly.” He finally hit the jackpot on July 6, 1952, but didn’t actually realize it until three weeks later, when he examined a sample with a Geiger counter and the needle fluctuated rapidly.

The high-grade deposit at Big Indian Wash, south of Moab, Utah, became recognized as one of the most important uranium discoveries. Seen made millions off the site, which he named “Mi Vida.” Cisco, the remote water-refilling station grew to house a population of 250 people. Nearby Moab saw its population increase by some 5,000 people, as mining camps also popped up outside of other communities. Steen did not hesitate to live large with his fortune and make up for the desperate conditions his family had endured in those early prospecting years, building a mansion complete with a greenhouse and quarters for growing domestic hemp. Many prospectors were inspired by Seen’s success story of supposedly making over $130 million from his discovery. While Steen went on to create a number of companies in the uranium trade, the eventual downturn came in the market when the AEC realized it had enough of the material. Steen’s frivolous spending left him in financial ruin and Cisco became a ghost town once again.

The Manhattan Project, the famed research initiative captured in the recent film Oppenheimer, had largely relied on imported uranium, notably from Canada and the Belgian Congo (there was always fear that there wouldn’t be enough of the material for the burgeoning nuclear weapons program).

There’s a town in Canada named Uranium City, although these days it’s mostly an abandoned village. When its mines were closed down in 1982, the town had a population of 2,507, with schools (named after the nuclear reactors), a hospital, restaurants, stores and public transport. Despite the economic collapse caused by the closure of the mines, some 75 residents decided they would try and hold on. Today about 50 of them are still living there, about the same as the number of former uranium mines abandoned in the area.

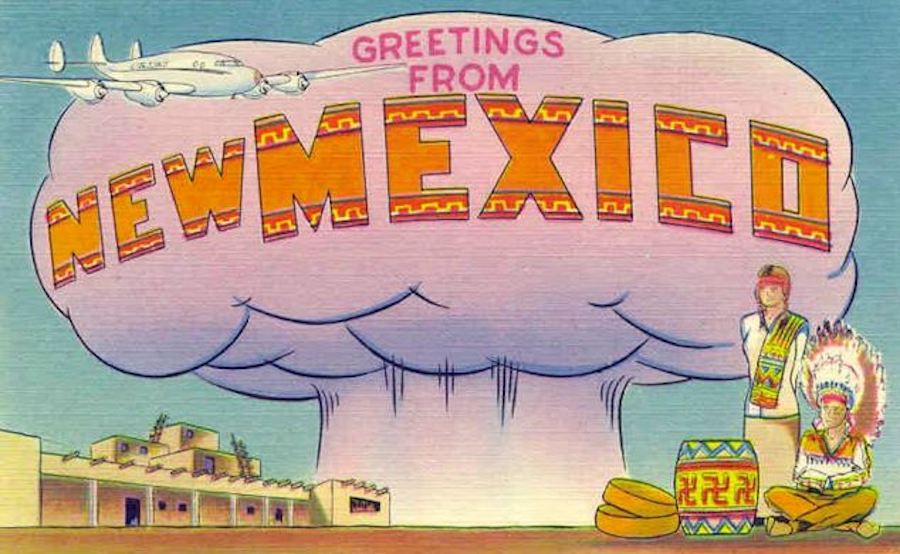

The 1946 Atomic Energy Act allowed the AEC to withdraw private sector lands that could be possible uranium mining spots. The commission also artificially set the price of uranium (which had previously been relatively low as it was mostly used as a pigment for ceramics) to encourage prospecting, particularly in the Four Corners region, which encompasses the Southwestern states of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah. Some 900 mines were opened across the Colorado Plateau, most with little regulation.

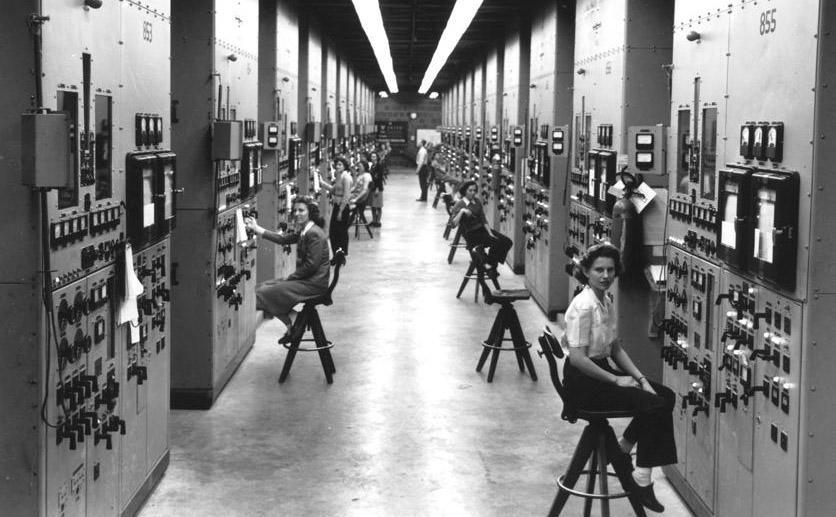

A uranium town of some 800 people at its peak in western Colorado, Uravan (see what they did there) was established as a mining town for vanadium, a byproduct of which was uranium. The Manhattan Project built a new mill there in 1943, but the work was kept top secret. Even the workers didn’t know they were contributing to the atomic bomb. Even worse than not knowing the nature of their work was the long-term health consequences of mining uranium, notably lung cancer. Sadly, it was not only the bust of the uranium cycle but the impact of radiation that created some of these ghost towns and “uranium widows,” as the New Yorker reported in 2010. And the consequences continue on for future generations, with higher rates of birth defects.

While there are some towns like Elliot Lake in Ontario (founded in 1955) dubbed “the uranium capitol of the world” which managed to recover from the 1980s uranium market collapse and diversify, others were not so lucky. The uranium mining industry thrived for four decades in the Navajo Nation but left disease, pollution and the biggest radioactive spill in US history (America’s conveniently forgotten nuclear disaster). The spill in Church Rock, New Mexico, upended the lives of nearby residents, who had to grapple with toxic water, livestock and a lifetime of illnesses. Now, they are still waiting for it to be cleaned up. And it’s still happening to many other towns.

It wasn’t until 1990 that Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation. Secretary of the Interior (1961-1969) Stewart Udall, who represented families of Navajo Indians that died as a result of mining conditions in New Mexico, said the government had “needlessly sacrificed the lives of [the Navajo miners] in the name of national security.”

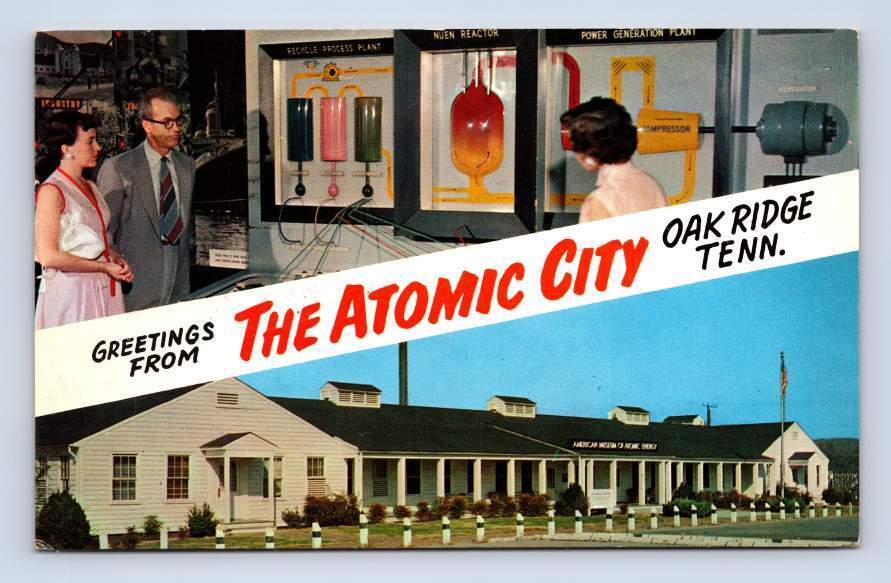

We’ll end our tour of North America’s uranium ghost towns with a living one. The “Atomic City,” in Oak Ridge, Tennesse, was one of the primary secret locations of the Manhattan Project, where 75,000 residents had no idea they were processing uranium until the bombs dropped on Hiroshima in 1945. Although was never the site of a mine, several years ago, we published a story about life inside the atomic city with rarely-seen photographs documenting everyday moments of a seemingly normal suburban American town during World War II, as well as the residents performing their mysterious ‘tasks’ and ‘duties’ inside the secret nuclear facilities. The historic K-25 uranium-enrichment plant wasn’t demolished until May of 2013, while the Y-12 facility, originally used for electromagnetic separation of uranium, is still in use for nuclear weapons processing and materials storage. The U.S. government is still the biggest employer in the Knoxville metropolitan area where Oak Ridge is located.

“We often think of peace as the absence of war, that if powerful countries would reduce their weapon arsenals, we could have peace. But if we look deeply into the weapons, we see our own minds- our own prejudices, fears and ignorance. Even if we transport all the bombs to the moon, the roots of war and the roots of bombs are still there, in our hearts and minds, and sooner or later we will make new bombs. To work for peace is to uproot war from ourselves and from the hearts of men and women. To prepare for war, to give millions of men and women the opportunity to practice killing day and night in their hearts, is to plant millions of seeds of violence, anger, frustration, and fear that will be passed on for generations to come. ”

– Thich Nhat Hanh, Vietnamese monastic and peace activist