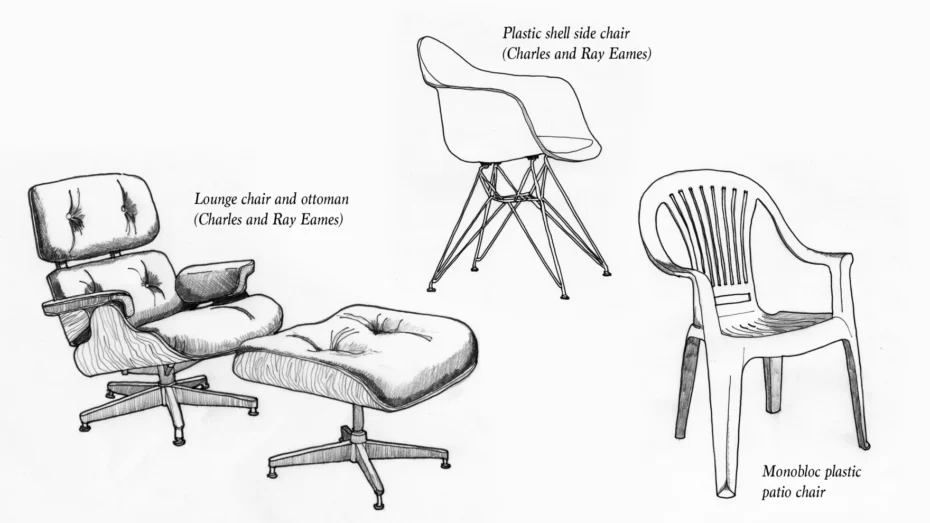

One of the ultimate icons of modernity and mass production must be the famously infamous wobbly plastic monobloc chair. Found across the globe, from homes to hospitals, gardens to grasslands, base camp Himalayas to frosty Antarctica, this migratory masterpiece of furniture has followed humanity to the far corners of the earth like a faithful hound. Like its carbon-based users, it too has a rich and varied life full of tales to tell. Born shiny and colourful, taking pride of place on manicured lawns, populating waiting rooms and congregating in church halls alike, its life cycle inevitably lets it retire to camping expeditions or flea market stalls and ultimately to decay … peeling, with amputated legs and fractured arms, till it finds it its ultimate resting place in a landfill tomb. Gone from the world of sunlight above to the dark underworld, its plastic bones outlasting the most enduring dinosaur fossils.

The so familiar, so ordinary and so expected chair for common use is a relatively modern thing. Chairs in ancient times were special, designed and reserved for those in authority, symbols of the state and leadership, thrones for kings and gods. The ancient Egyptians had them, Ramses and his Pharaonic family often carved as sitting giants, while the Minoan Place at Knossos provides only one for somebody very important. The Greeks and Romans had their folding cross-bent egged Curule chairs too, but the common man was not comfortably seated until the 16th century, and really only in Europe. By the 19th century, industrialisation put the affordable chair in the reach of many. Most notable was the classic Thonet bentwood chair. Come the 20th century, production technology, new materials and social revolution ensured we could now all be seated on thrones cast from a variety of materials, shapes, colours and sizes. Post WWII, globalisation and easier access to raw materials, notably from the house of oil, saw the accession of the plastics dynasty, more than able to provide bendy, shiny, colourful and cheap enthronement for the masses.

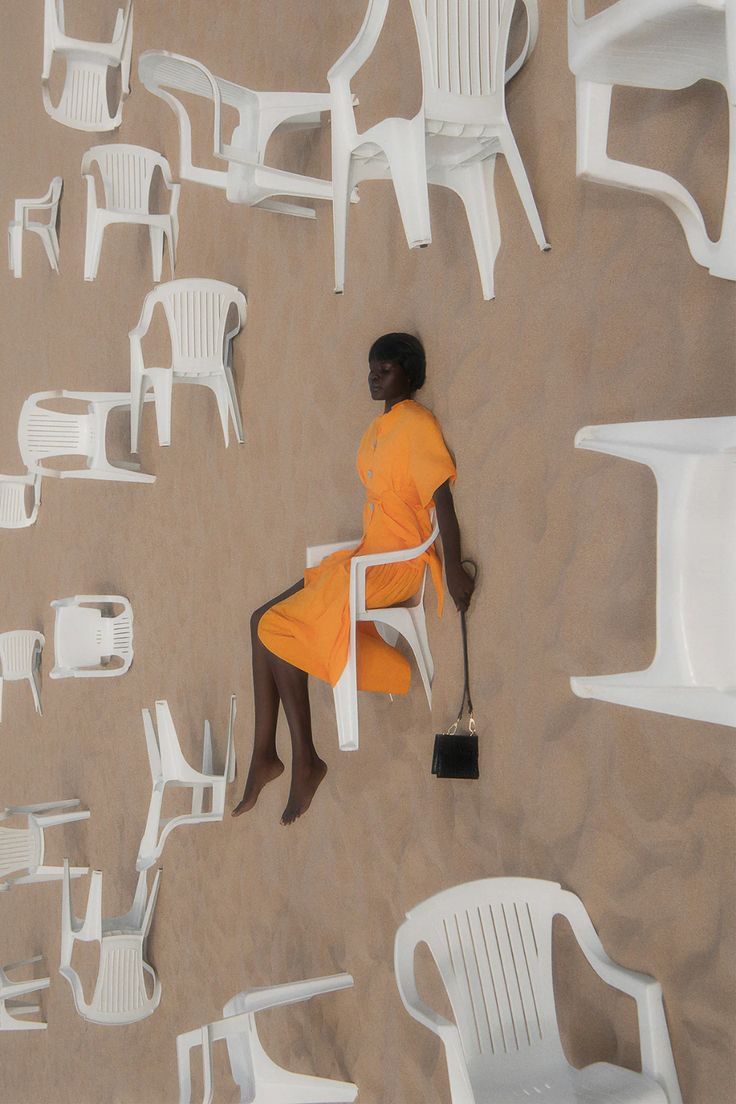

Always suspicious of its bearing capacity, we pull out the monobloc chair, inspect it and cautiously lower ourselves into its arms, somehow always expecting imminent collapse. Rather miraculously, after that intriguing moment of compression, the monobloc is comfortable, supportive and strangely flexible, unlike many other chairs. Cushioning, upholstery, padding, horse hair, leather, nails, studs or whatever are not present, nor required. The suspension in this soft and silky sling is intoxicating and almost alive. Unlike any other chair, the humble monobloc is cheap as chips, lightweight, robust, flexible, waterproof, also surprisingly stackable and moveable in quantity. Like a faithful steed, it’s seemingly always available, the perfect product for those large infrequent gatherings, in the wet or in the dry.

Instantly recognisable and enduringly popular, many have claimed authorship of the monobloc or ‘one-piece stacking plastic chair’. D C Simpson in Canada in 1946, Henry Massonnet in 1972 or the ‘Chair Universal’ designed by Joe Colombo in 1965, are all contenders to have their name on the monobloc. No patents were ever filed, so unusually in the contemporary corporate copyright world, the monobloc is actually royalty-free; a true people’s chair.

It is estimated that in the second half of the 20th century over a billion monobloc chairs were sold in Europe alone. Essentially a single piece of injection moulded plastic, the variation in detail is almost infinite; design, colour, shape and texture. Two heavy steel hydraulic mould halves have a small amount of heated, coloured thermoplastic polypropylene melted from granules to 220 degrees Celsius injected into the space between them, and are then almost immediately parted. The chairs cost little more than 3 US dollars to produce, with some manufacturers able to output over 10 million units a year.

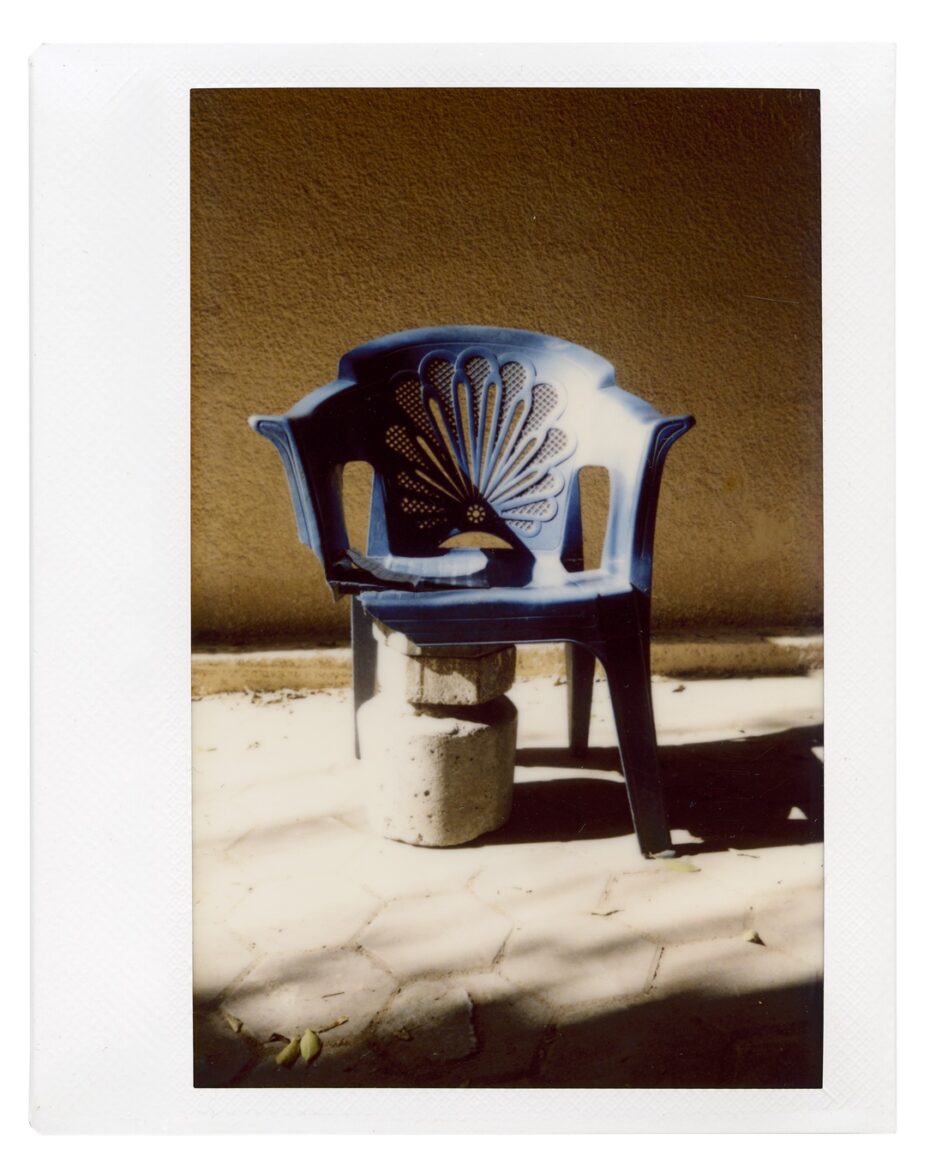

Being plastic, our flexible friend does not enjoy direct sunlight or other weather extremitiwa and (much like ourselves) is subject to colour-fading and peeling. A quick facial from the healing flame of a blowtorch however can burn away the years and restore the plastic oils to the surface for a new youthful look.

But the very strengths of the chair are its weaknesses. It’s extremely difficult to make structural repairs unlike nailing and screwing of its wooden cousins; once a leg is broken, it’s detached forever, no glues or potions can bring the plastic bits together again. Once disabled, its worthless, it cannot be recycled in any form, not even as firewood. Being of a plastic type, it never rots nor decays, it’s fate is to never die, it can only be sent to the landfill pit for an endless sleep.

The humble monobloc has been ridiculed as a real evil of global industrialisation, yet extolled as a true piece of ‘perfect design’. In 2022, contemporary artist Krassimir Terziev displayed a monobloc garden chair titled ‘the globe’s lowest common denominator’. This so egalitarian of products is now vilified, the unacceptable face of runaway mass production, wanton resources, exploitation and insoluble pollution. It seems that the throne of the common man was just too easily acceded to, he was never meant to be king and will now collectively pay the price of ambition. There must be fable in the wings, like Icarus and Lazarus or Midas, even Prometheus … mankind being punished for his success.