Deep inside one of the last remaining primeval forests in Europe, in-between Belarus and Poland, stands an old hunting lodge straight out of a fairytale. For over 30 years, ecologist Simona Kossack lived in this secluded glade without amenities nor electricity or running water and with an unusual band of forest friends. There was a crow with kleptomania, a lynx named Agatka, and a 400lb female boar called Froggy. The descendant of a renowned lineage of artists from Poland, she had chosen naturalistic seclusion and the language of the forest over the modern world. Her own family would become the animals that surrounded her and she would spend a lifetime studying and befriending them as she attempted to understand and preserve their decreasing habitat. Simona would document her life in film and write about the natural world as she attempted to convey the importance of our fragile connection with nature.

What makes us seek seclusion? hHistory is littered with tales of people severing ties with their present and seeking something more primal that existed in their genetic past. Various Writers, painters, and holy men have all felt the call of the wild, and then there are the people who just didn’t feel that they belonged in their circumstances. Simona Kossack had grown up in a family where creative proficiency was an inherent expectation. Born in 1943 in Krakow, the Kossack’s were disappointed not just in the lack of producing a male heir but Simone had been born with a cleft palette. Communication was difficult and as she grew, they determined she had no discernible creative talent. Simone had been given the title of the black sheep of the family; the outcast. From a young age, she turned away from the expectations and criticisms of her family and found solace in the animals that were plentiful around her rural home. This first tentative connection would be the beginning of her ardor for nature.

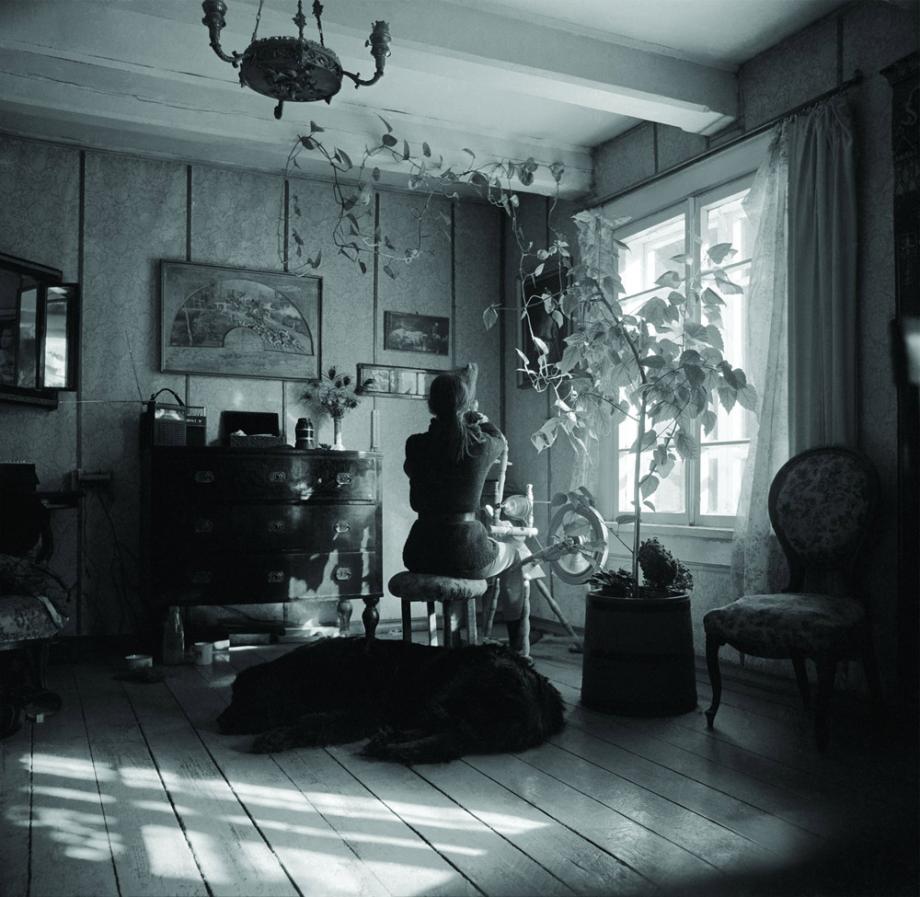

Simone Kossack would struggle through school and forming relationships with people but eventually secured a place at Jagiellonian University in Kraków where she would complete her degree in Zoology and animal behavior in 1970. Her real education would begin when she secured a job with the Mammal Research Institute in Białowieża National Park. This is where she found her seclusion, and her home, a run-down, seemingly haunted hunter’s lodge called Dziedzinka that was in danger of being devoured by the forest. It was surrounded by Aurochs, a now-extinct ancestor of the cow. She fell in love with the place immediately.

It was the first aurochs that I ever saw in my life – I am not counting the ones in the zoo. Well, and this greeting right at the entry into the forest – this monumental aurochs, the whiteness, the snow, the full moon, whitest white everywhere, pretty […] and the little hut hidden in the little clearing all covered with snow, an abandoned house that no one had lived in.. In the middle room, there were no floors; it was generally in ruins. And I looked at this house, all silvered by the moon as it was, romantic, and I said, ‘it’s finished, it’s here or nowhere else!‘

This ramshackle home would be Simone Kossack’s salvation; the centre for the study of the animals that inhabited the forest. After some restoration work on the abandoned cottage, Simone set out to learn the language of the woods and began to invite animals inside her home. An owl, several buzzards and an injured hedgehog made Dziedzinka their home, and later someone Simone hadn’t invited.

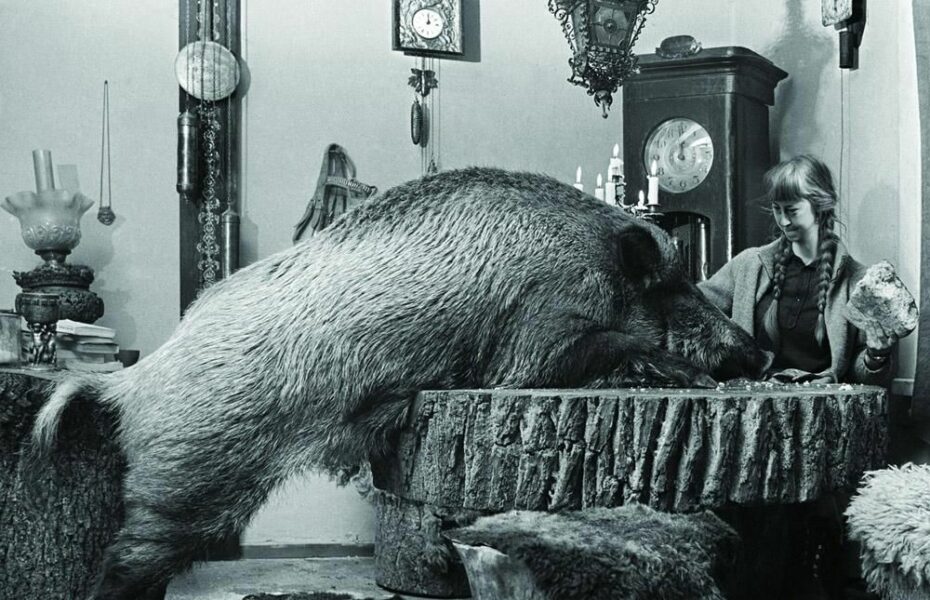

A male photographer called Lech Wilczek, set up camp in the second part of the house after obtaining permission from the National Park services. Kossack was dubious of this interloper, she’d had bad experiences with the two-legged variety of mammals and she wasn’t quick to trust. Wilczek was a well-known Polish wildlife photographer and naturalist, his love for nature and environmental issues would rival even Kossack’s and after a rocky start, a mutual respect and harmonious cohabitation would ensue. The fact that Lech had brought an orphaned wild boar home one day to live with them helped, and their mutual love and respect for the forest would result in a collaboration of art and passion. Lech would document their lives and relationship with the natural world as well as their growing love for each other.

The wild boar who was christened Zabka (Froggy) would sleep in their beds and followed them around, behaving more like a pet dog than the tusked colossus it would grow into. Visitors would have to be wary of this giant; it was a sensitive but highly protective guard pig when approaching Dziedzinka. Next, to be added to the menagerie was the cantankerous flying menace that would become the scourge of the area, Korasek the crow.

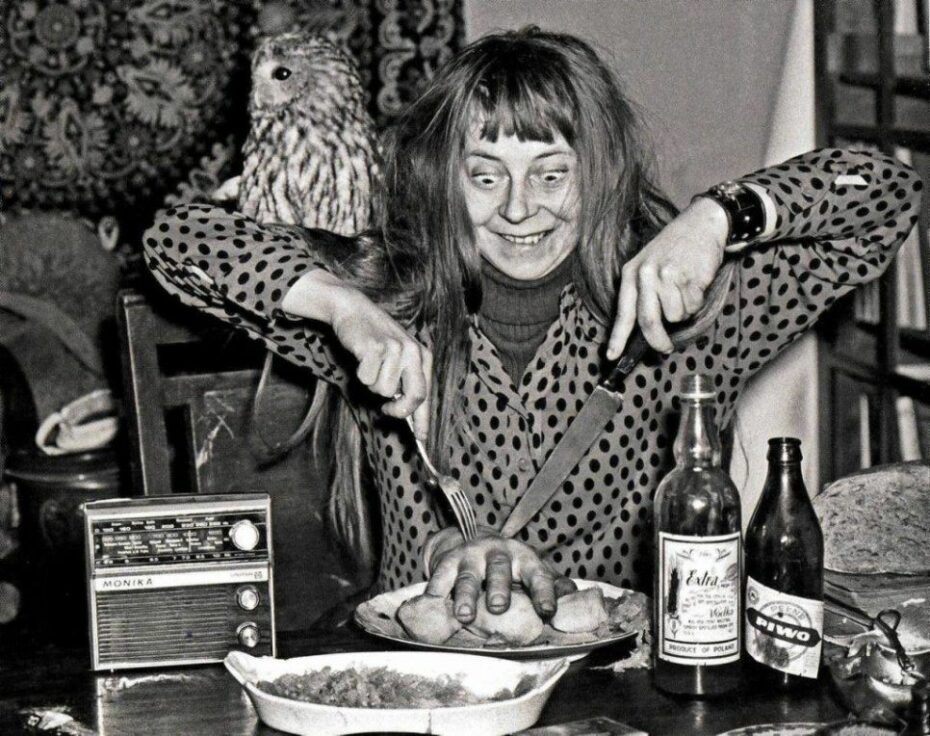

A bad-tempered carrion with a mean streak, Korasek would steal anything he took a liking to. Nothing was safe, keys, food, money, items of clothing (people were wearing), documents, cigarettes, and hair brushes. He was known and feared around the region, but fearlessly loyal and Lech’s best friend. A local resident Stanisław Myśliński remembers…

‘He would even steal workers’ pay in the woods. He once stole my permit for entering the woods. He pulled it out of my pocket and notoriously tore it apart. He loved to attack people who rode bicycles, especially girls. It was very impressive – he would attack the rider’s head with his beak, the person would fall off, and he then would sit on the seat triumphantly, looking the at the spinning wheel’.

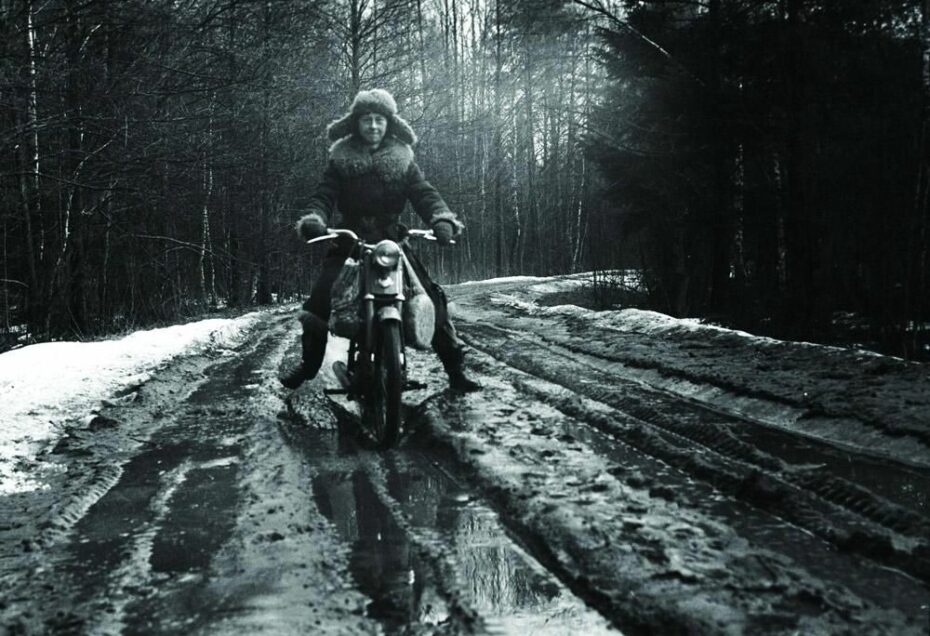

As Simone Kossack and Lech Wilczek’s relationship grew, so did their collection of animals; there was a donkey, a doe, twin moose calfs Pepsi and Cola, a stork, peacocks, lambs, rats, and the female lynx cub Agatka, whom Kossack referred to as her daughter. All were welcome at Dziedzinka; waifs, and strays, the abandoned and the injured, everything was cared for and loved. Kossack would be seen as a spirit of the forest, a part of ancient folklore believed by the locals to be a witch; the one who talks and walks with the animals, a healer, and a protector.

Simone may have been all these things but she was also an environmental activist and ecologist who would come to refer to herself as a zoo-psychologist. She continued her work for the Institute at the Department of Natural Forests and gained her doctorate in 1980, eventually becoming a professor of forest sciences. She would go on to publish two books and write articles, produce films, and complete hundreds of scientific studies. In 2000, the Polish government awarded Simone Kossak the Golden Cross of Merit, the highest civilian award for her work and research in aid to protect Poland’s last primeval forest. Then in 2003, she was appointed Director of the Department of Natural Forests, a role she would maintain until her death.

Kossack and Wilczek would spend the rest of their lives in their secluded sanctum, surrounded by a family of animals, finding contentment that was lacking in the modern world just beyond the edge of the forest. After Simone Kossack died in 2007, Lech Wilczek published a book, Meeting with Simona Kossak, in 2011 and in 2022 the documentary film called Simone was released.

Man is also a part of nature, and there are no more or less important parts in it. A flower, a star, a stone, a man is permeated with the same divine spark. Those who learn to sympathize with plants and animals can understand others and will be better for themselves, that is, they will do nothing against their nature.

Simona Kossack.

All Photographs By Lech Wilczek and Simona Kossack.