London of the 1920s was the time of the Bright Young Things, the group of aristocrats and socialists who flourished in the years following World War I and before the economic crisis that would hit the globe at the end of the decade. And there was no other place that served more as a central hub of this movement — and the broader cultural and business elite of the era — than the Gargoyle, a private club the likes of which have never been seen since.

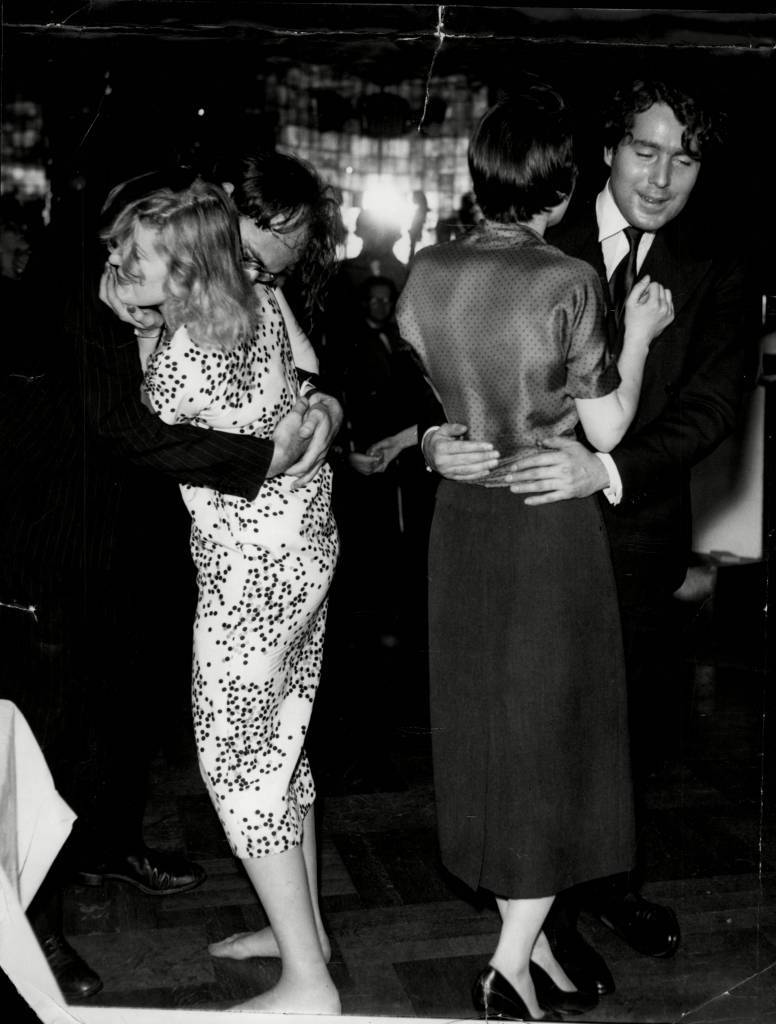

Located in the lively Soho neighbourhood, the Gargoyle was opened in 1925 by David Tennant (no relation to the Scottish actor), a founding Bright Young Things member who supposedly just wanted a place to dance with his girlfriend (actress Hermione Baddeley, known for taking on highly risqué roles). David’s brother Stephen was considered the centre of the movement that seized opportunities to express themselves through mediums like clothes, music, and sexuality.

Tennant rented the top three floors of the building, located at 69 and 70 Dean Street. It was rumoured that the building was haunted by Nelly Gwyn, a fruit seller and actress who was also a mistress of King Charles II. (She supposedly appeared as a grey figure accompanied by the smell of gardenias). Whatever the case, Tennant modernised the space with a ballroom, coffee room, drawing room, private apartment and Tudor room, as well as an expansive roof-top garden for dancing and eating. The design project was a collaboration between architect Edwin Lutyens and none other than artist Henri Matisse. No expense was spared in creating an opulent setting.

There were fireplaces in the dining room (which could seat 140), a fountain on the dance floor, a gold leaf-painted ceiling and gargoyles made of wood that served as lanterns. Moorish influences were strong, including mosaic work. Matisse designed a breath-taking steel and brass staircase. The glass in the dance hall came from a French chateau and the famed painter said he wanted it to be “covered in small squares of old French mirrors, cut up to produce a general sparkle.” Work by Henri also covered the walls, notably The Red Studio (derided at the time but now one of the artist’s most famous pieces for its radical use of color), which hung behind the bar. Other works, The Studio and Quai St Michel, which portrays his favorite model, Lorette, was located along the staircase.

Writer and member Stanley Jackson described the club in his 1942 An Indiscreet Guide to Soho: “The decor is bright but tasteful and Matisse gave his expert advice. Several of his drawings of ballet girls grace the upstairs bar which is a cheerful spot always crowded with people discussing art, politics or women in the liveliest way. ‘My unpaid cabaret,’ David Tennant calls them…The restaurant downstairs seats 140 and its ceiling and general design have been modeled on the Alhambra at Granada. The mirrors are particularly attractive, unless you have drunk too much gin! The four-piece band led by Alec Alexander, suits the style of the club. It delivers lively, cheerful music that you can dance to without having your nerves torn to shreds. Alec knows all the members and seems to enjoy playing requests.”

Despite the opulence, everyone lucky enough to enter the Gargoyle did so through a tiny, rickey external elevator. And getting the chance to go was truly a not to be missed opportunity. The Daily Telegraph wrote of its opening night that the member list, which included some 300 people, “probably contains more famous names in society and the arts than any other purely social club.”

This highly selective crew included artists like Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud, Caroline Blackwood and Lee Miller; writers like Virginia Wolf, Dylan Thomas, Somerset Maugham the Mitford sisters and Noël Coward; actors including Fred Astaire, Gladys Cooper and Gordon Craig; and those coming from the most wealthy families, like Edwina Mountbatten and members of the Guinness, Rothschild and Rothschild clans. Membership cost four guineas per year.

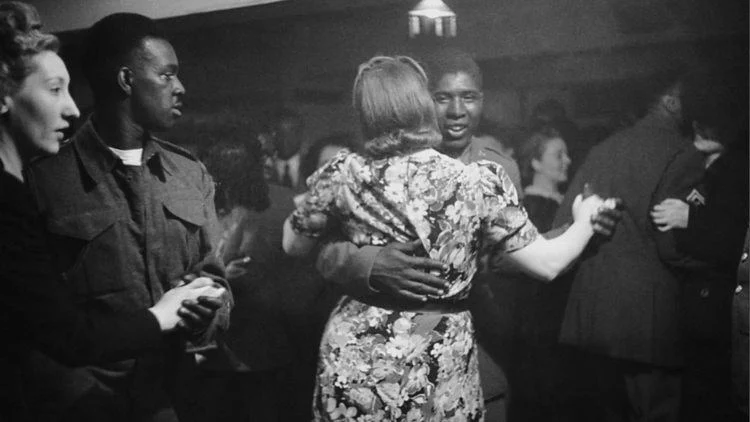

During the day, the club was popular for work lunches before being transformed into the hottest spot for nightlife, what composer Constant Lambert described as packed with “the two hundred nastiest people.” Long nights would lead to early morning after-parties at the Cavendish Hotel, another Bright Young People (BYP) haunt. Their shenanigans were captured by photographer Cecil Beaton, and members would not hesitate to dress up for the occasion, often wearing old-fashioned regalia and other extravagant looks. (Costume parties were de rigueur.) As British writer and BYP member Daphne Fielding said, “They even began to dress differently,” as the Bohemian influence spread to be a larger trend. Tennant, for his part, described it as his “unpaid cabaret,” where it was just as common to hear someone conversing about art as about current political debates, with a jazz band led by Alec Alexander playing and the alcohol flowing.

The coming war years dealt a blow to the BYP, not the least because some of its members proved to be on the wrong side of history, notably John Amery, who was a Nazi collaborator and sentenced to death for treason. Despite some BYP’s members queer identity and interest in leftist politics, many others had far-right and even fascist tendencies. While the Gargoyle was still frequented by the likes of British diplomat Guy Burgess, who was also a double agent for the Soviets, it ultimately fell out of popularity.

In a tight financial situation, Tennant sold the club in 1952. It went through many entertainment iterations, even serving as a strip club called Nell Gwynne. In 1982, it hosted the first iteration of the weekly club-night Batcave, which featured artists like Nick Cave, Siouxsie Sioux and Robert Smith.

Nowadays the decadent Dean Street Townhouse holds down the fort, even continuing to be a spot for encounters among today’s who’s who. In fact, Prince Harry and Meghan Markle had their first date there in 2016.