There’s a song that went viral on TikTok recently (seven years after its initial release), becoming the social media platform’s song of the summer. You’ve almost certainly heard it. “Ooohe, Makeba, Makeba ma qué bella,” sings the French pop singer, Jain, during the song’s chorus which has soundtracked over 5 million dance routines. But the question is, does any of TikTok’s 18-24 year-old demographic actually know who the song is about? As they post their synchronised twerking videos online using the hashtag #Makeba, does anyone know the story of the fearless diva, Miriam Makeba, who rose from the oppression of apartheid South Africa to lead and personify the struggle of people of colour across the world?

Miriam Makeba, nicknamed ‘Mama Africa’ and dubbed ‘Empress of African Song’, ‘Queen of South African music’ and Africa’s ‘first superstar’ was a divinely gifted singer, entertainer, evangelist, actress and advocate who became a symbol of Black resistance Her long and audacious career (she made over 30 albums and sold out innumerable prestigious concert halls across the world) saw her criss-crossing continents and rubbing shoulders with heads of state John F. Kennedy, Haile Selassie, Nelson Mandela, as well as stars of the silver screen; Marilyn Monroe, Marlon Brando, Louis Armstrong, Nina Simone and Ray Charles to name but a few. Not bad for a girl who started life in a prison cell with her mother.

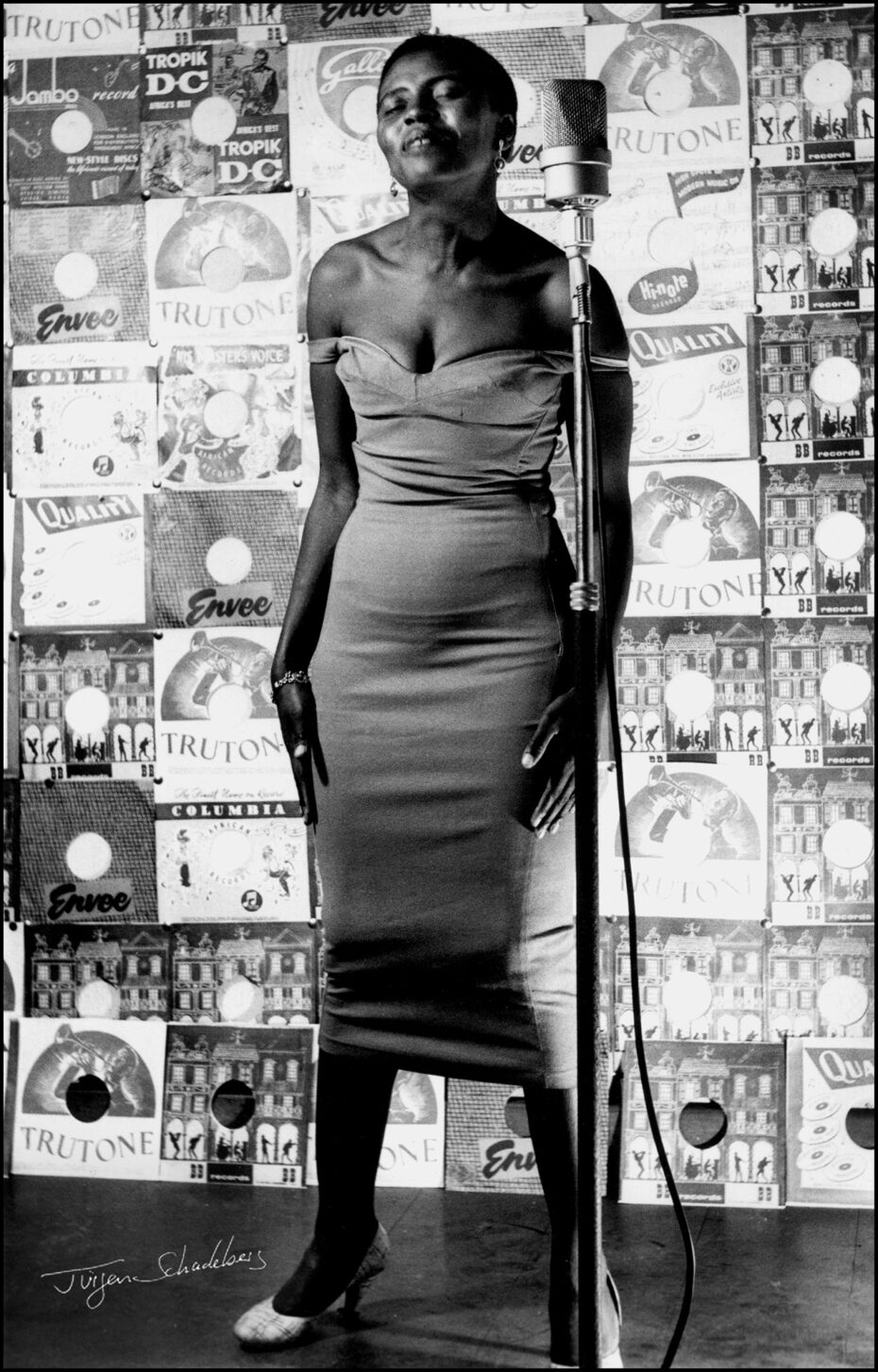

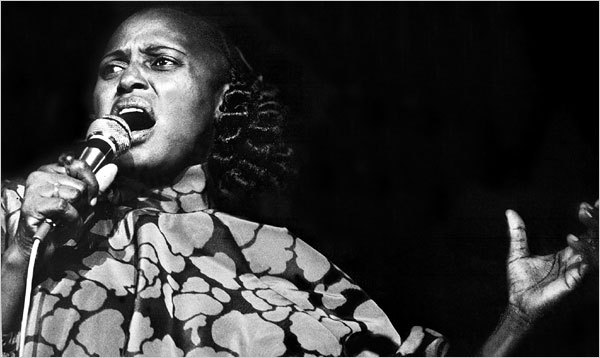

Shunned, exiled from her motherland for 30 years, stateless and disillusioned with her adopted country the USA, her story is a roller coaster ride of dogged determination, success, survival, and ultimately bittersweet triumph. Makeba began with music and ultimately died in music; her sound described as a ‘unique blend of rousing township styles and jazz-influenced balladry.’ Her performances were enigmatic: she was sensuous, emotive and intimate on stage, her voice and range were exceptional. A commentator once remarked, she “…could soar like an opera singer, but she could also whisper, roar, hiss, growl and shout. She could sing while making the epiglottal clicks of the Xhosa language.”

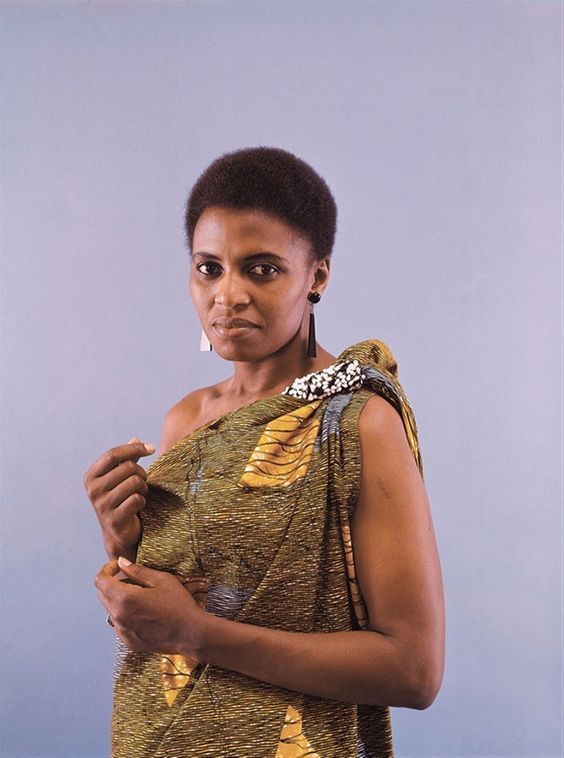

Newsweek equated her voice to ‘the smoky tones and delicate phrasing’ of the legendary Ella Fitzgerald’s and the ‘intimate warmth’ of Frank Sinatra’s. African through and through, she promoted ‘Black is beautiful’ and advocated African feminism. In her native South Africa, she was considered as both sex symbol and style icon. Her no-make-up look, un-straightened hair and unbleached skin (skin-lighteners were commonly used by South African women at the time) together with the African jewellery she proudly wore, presented a “liberated African beauty aesthetic”, notes music scholar Tanisha Ford.

Her life story reads like a Hollywood film script, a drama of unbelievable highs and tragic lows. Her musical career was the constant that held together her personal and political lives. Her mother was Swazi – a sangoma or traditional healer, and her father Xhosa – a teacher, who died when she was six. Life started for Miriam in the humble township of Prospect outside Johannesburg, but in reality, in prison, at just 18 days old, when her mother couldn’t afford the fine to avoid a six month prison sentence for brewing homemade beer. Young Miriam lived with her grandmother in a house full of cousins while her mother worked away as a domestic help for white families. Miriam’s family was musical: her mother was versed in traditional musical instruments and her father played the piano; her elder brother collected Ella Fitzgerald’s and Duke Ellington’s records. The shy but irrepressibly talented Miriam embraced music and made her debut in the local church choir. Perhaps a taste of the rocky road ahead, what should have been the highlight of her young career turned to disappointment when she was told to sing “What a Sad Life for a Black Man” for the visit of King George VI. After a long wait in the rain, the royal guest drove by without stopping to hear the children’s song.

At only 17, Miriam married a policeman, James Kubay, who left her shortly after having her first and only child, Bongi. Her commercial musical career kicked off with a harmony group the Cuban Brothers and at the age of 21, she joined the Manhattan Brothers, singing a mix of South African and American songs, and it’s here that she recorded her first hit, Laku Tshoni Ilanga in 1953. In 1956 she joined an all-female group called the Skylarks (also known as the Sunbeams), the vocals later lauded by the music historian Rob Allingham as “real trendsetters, with harmonisation that had never been heard before”.

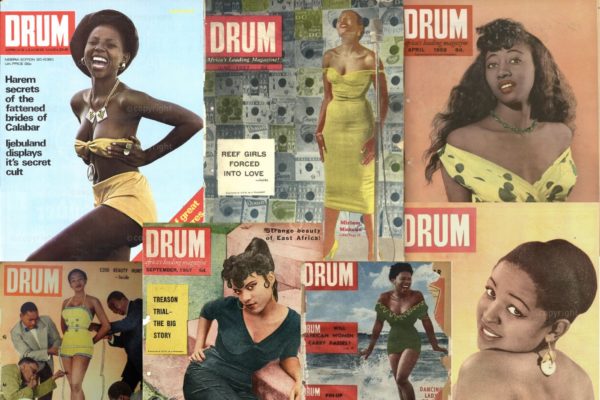

Miriam had a magical aura, a certain je ne sais quoi, so much so that when Nelson Mandela (then a young lawyer) met Miriam Makeba in 1955, he instinctively felt she “was going to be someone.” Her first solo success was Lovely Lies, in which the Xhosa lyrics were ‘adapted’ to suit a Western audience and in 1957 it became the first South African record to feature on the USA Billboard Top 100. In 1957, she featured on the cover of South Africa’s Drum magazine, one of the first Black lifestyle magazines in Africa.

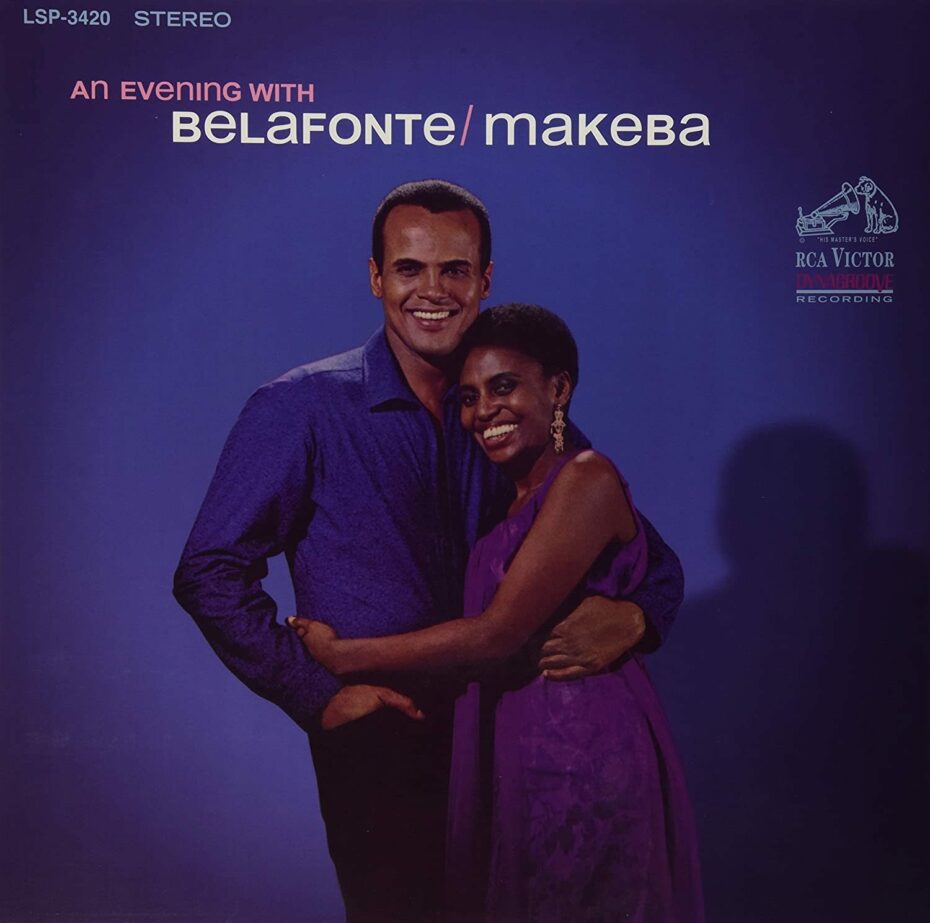

In 1959, Miriam Makeba first met another South African trumpeter and music legend, Hugh Masekela, while auditioning for the lead female role in King Kong, a South African jazz opera (about the life of a boxer) – a meeting of profound consequences (more on that later). Miriam’s cameo role in American filmmaker Lionel Rogosin’s anti-apartheid film Come Back, Africa – also in 1959, wowed audiences and Miriam was whisked off to attend the premiere of the film at the 24th Venice Film Festival (the film went on to win the prestigious Critics’ Choice Award). International recognition and a jet-setting showbiz life between New York and London followed. Miriam next made the key acquaintance of her career in American singer Harry Belafonte in 1960, who would remain her mentor for many years.

Harry Belafonte was a constant presence; he took a personal interest and directed Makeba’s flourishing career in America. In 1960, she released her first studio album Miriam Makeba, containing the now famous ‘Click Song’, backed by Belafonte’s band. Makeba and Belafonte performed together at President John F. Kennedy’s birthday party in 1962 before she released a second album, The World of Miriam Makeba, introducing world music to an international audience. Makeba and Belafonte received a Grammy Award for the album An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba in 1965, making her the first African woman of colour to win a grammy. The now iconic Afropop gem Pata Pata followed in 1967 – regarded as Makeba’s most famous song (although she shrugged it off as “one of her most insignificant songs”). Unfortunately, while recording Pata Pata, Makeba and Belafonte fell out for unknown reasons and stopped recording together. Across the Atlantic, she debuted on the Steve Allen Show in 1959, her performance lapped up by 60 million; critics and audiences adored her.

Meanwhile back in South Africa the fateful Sharpville massacre took place in 1960 (two of Makeba’s relatives were killed there) and she could remain politically silent no longer. Upon criticising South Africa’s ruling National Party at the UN, Makeba attempted to return home for her mother’s funeral only to discover her passport had been cancelled and her music records banned. Panicked, she sent for her 9-year-old daughter Bongi to join her in the States. Sharpeville was a milestone in Miriam’s life; up until this point she had avoided political messaging in her music, but from here onwards, she became an outspoken critic of the apartheid system, saying poignantly, “In our struggle, songs are not simply entertainment for us.” US critics condescendingly called her the ‘African tribeswoman’ and an ‘import from South Africa’.

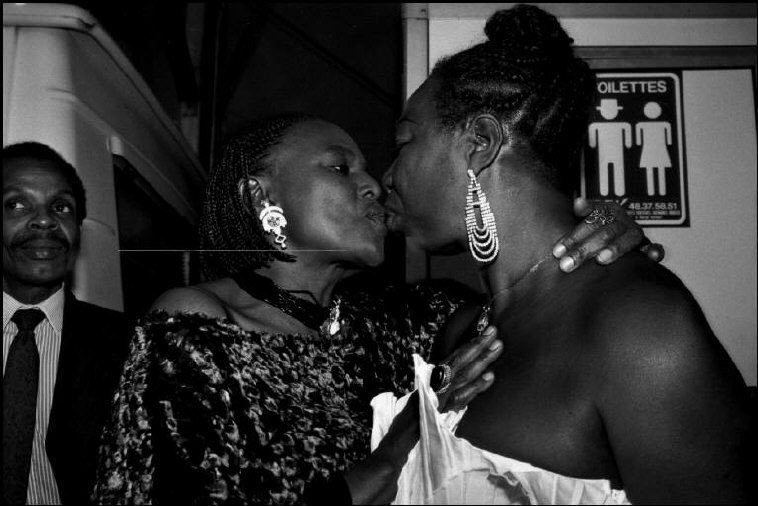

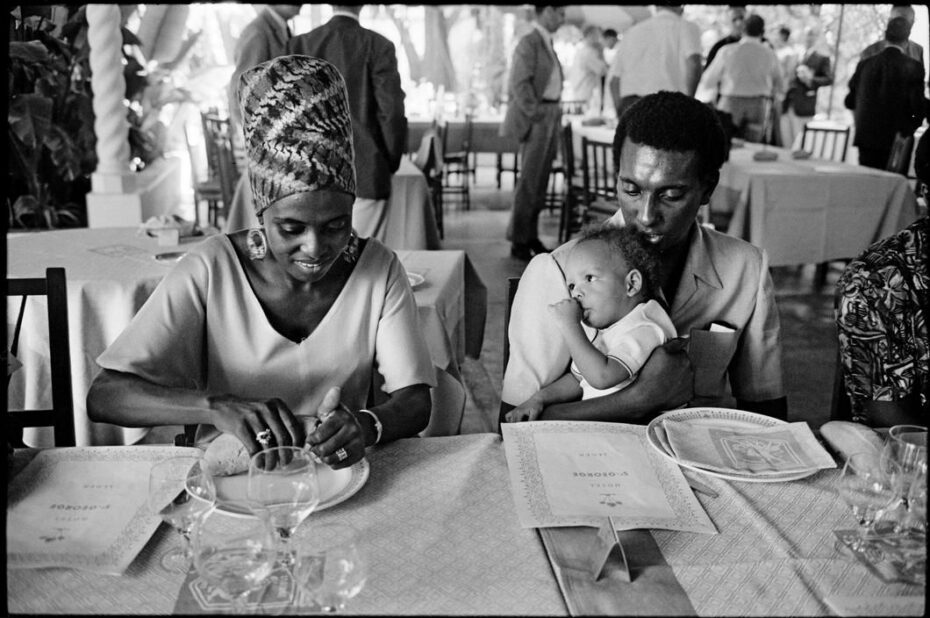

When her South African passport had been withdrawn, she was offered passports from nine countries and granted honorary citizenship in ten; Western liberals celebrated her bravery. Her music appealed to both white Americans (who perceived her as ‘exotic’) and Black Americans who could relate her struggle with theirs. During the mid 1960s, she married for the third time, to Hugh Masekela, and rubbed shoulders with stars like Dizzy Gillespie, Marlon Brando, Lauren Bacall, Louis Armstrong, Ray Charles and Nina Simone – with whom Makeba notably performed at Carnegie Hall.

By now Makeba was regarded as one of the key activist-performers who used her cultural popularity to shine the light on political injustice in society. Of the USA she famously said, “There wasn’t much difference in America; it was a country that had abolished slavery but there was apartheid in its own way.”

Makeba became a nomadic radical, carrying her message through performance across Europe and around the globe. She visited Kenya in 1962, supporting independence from British rule. The face and voice of civil rights and anti-apartheid, Makeba was involved in the Black Consciousness and Black Power movements.

Through Belafonte, she had met the prominent Black Panther Party figure-head, Trinidadian-American activist Stokely Carmichael, with whom she had a relationship and later married in 1968.

Disillusioned with Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s investment in South African companies, she declared, “Now my friend of long standing supports the country’s persecution of my people and I must find a new idol”. Makeba’s solidarity with Carmichael, who was regarded as extreme and militant, alienated many of her fans.

American audiences were skeptical; the CIA and FBI placed her under surveillance and soon banned her from re-entering the USA. Many Western countries such as France also barred her entry. With Carmichael, she moved to Guinea, which became her home for the next 15 years.

She became close to President Touré, who was keen to promote music in Guinea. Miriam deliberately wrote anti-US songs, bitterly criticising their racial policies, singing songs such as Malcolm X in 1974. She ventured more and more to the newly independent African countries that had shed their colonial shackles. The tragedy of the Soweto uprising in 1976, bringing the deaths of hundreds at the hands of the apartheid authorities prompted her former husband Hugh Masekela to write and Makeba to sing, the Soweto Blues. This is her most poignant and enduring protest song and is considered the anthem against apartheid.

She divorced Carmichael in 1978, turned down a marriage proposal by the president of Guinea and married an airline executive Bageot Bah instead, before moving to Brussels. Further strife ensued when Makeba’s daughter Bongi, a singer in her own right, died during childbirth in 1985. Makeba was left responsible for her two grandchildren. In Brussels, Hugh Masekela introduced her to Paul Simon and she went on to accompany the American singer-songwriter on his hugely successful Graceland world tour. Warner Bros signed Makeba and she released Sangoma, but her involvement with Paul Simon caused controversy; Graceland was recorded in 1986 in South Africa still under the apartheid regime, despite Makeba’s own endorsement of the cultural boycott.

Her autobiography Makeba: My Story drew on her experiences in South Africa and the USA. In 1988, she was part of the tribute concert for Nelson Mandela’s 70th birthday in London, broadcast to 600 million people across 67 countries. Mandela was released from prison in 1990, allowing Makeba to finally return to South Africa. Her studio album Eyes on Tomorrow followed together with a world promotional tour. In 1992, she received a Grammy Award for Best World Music Album for Homeland, amongst others. She was named a goodwill ambassador for the UN Food and Agricultural Organisation and worked closely with South African first lady Graça Machel-Mandela to combat AIDS and fought for the plight of child soldiers. She died as she had lived, both active and artistic. At a concert in Italy on November 9th, 2008, she died suffering a heart attack after singing Pata Pata.

And next time you hear that TikTok tribute song, know that you have a serious conversation starter on your hands.