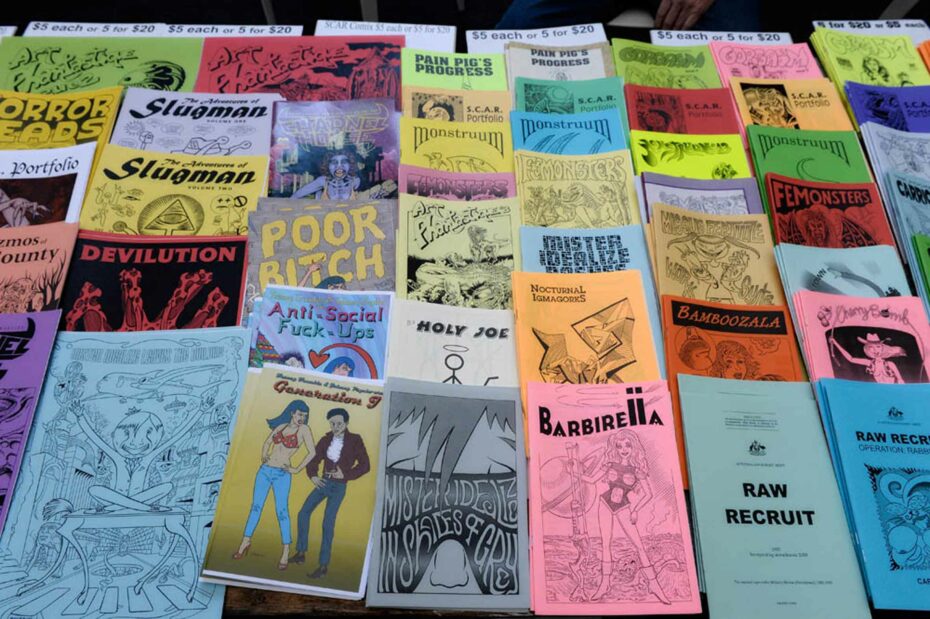

Let’s say you’re at a party, the air is thick with smoke and some cool cat on the couch looks at you funny and asks, “hey dude, do you even know what a zine is?” Don’t panic. Lean in close, clear your throat and remember: zines are whatever you want them to be and that’s the beauty of it. If you want to make for example, a dozen pages of collage art and poetry dedicated to the national treasure that is Steve Buscemi – you can most certainly call it a zine. They can be created by anyone with something to say, you just need to be passionate about something and have the desire to share it. Self-published, unrestricted pamphlets, high quality or low quality; zines can be used for expression, to inform, or to celebrate pretty much anything. Where does one find such cultural relics? Every city or town usually has that one place that’s still kinda cool enough to help distribute them; an independent bookstore, a café or a record shop. Since the beginning, zines have been made to pay homage to someone’s favourite band or subculture, to promote social and political change, or to champion a minority group. Using this medium, people have produced publications to celebrate queer culture and to subvert authoritarian rule, to promote an art movement or just to give a voice to the unheard, the only limits are the imagination of the creator.

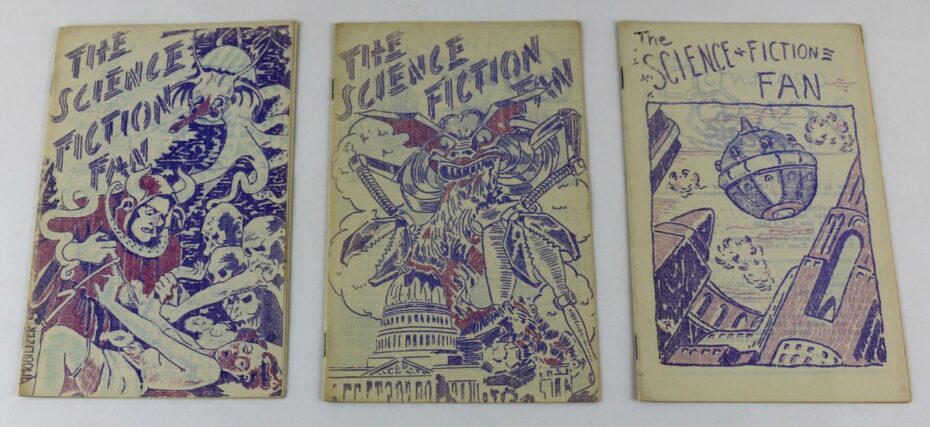

The origin of the first zine can be traced back to the 1930s “fanzines”, starting out as a platform for science fiction fans to share their love of the genre; a way to communicate and express themselves through art and ideas. The zines were hand made then, printed using mimeographs (low-cost duplicating machines that worked by forcing ink through a stencil onto paper) and produced in short runs before photocopiers in the 1970s let the Zine enthusiasts produce larger circulations. These first attempts would be a labor of love for the fans of a particular show, film, or comic; and they were traded at science fiction conventions across the US.

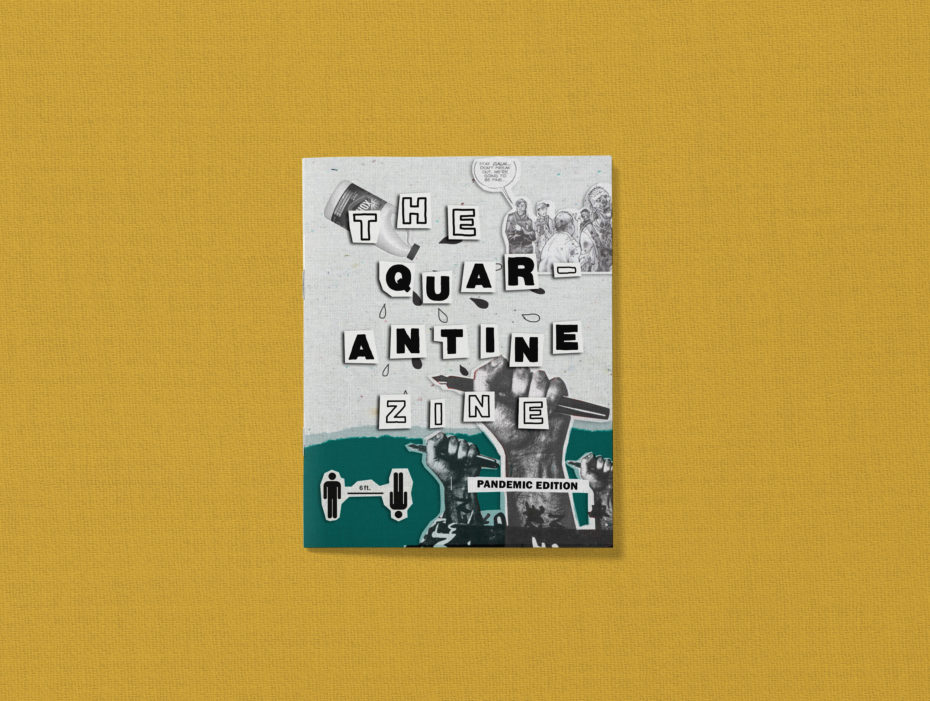

Zine makers didn’t have to be artists, graphic designers or have a gift for prose. A lot of zine makers employed the Dadaist cut-out technique from the early 20th century, a collage of image and text to communicate visually, but the aesthetic wasn’t stapled to any strident specification even if the pages were held together as such. Early Sci-Fi writers like Ray Bradbury and Robert A. Heinlein would start by producing their own fan fiction Zines to share their stories amongst the growing self-published community.

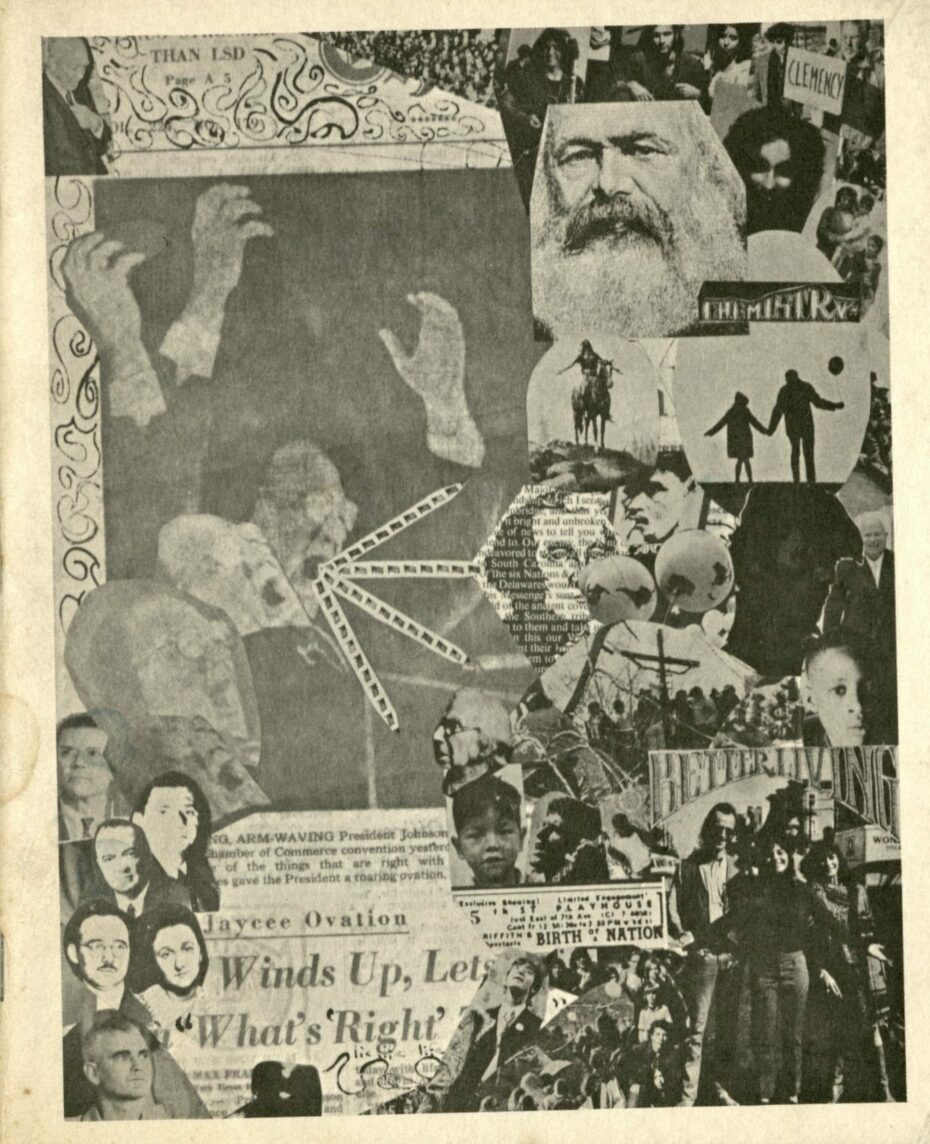

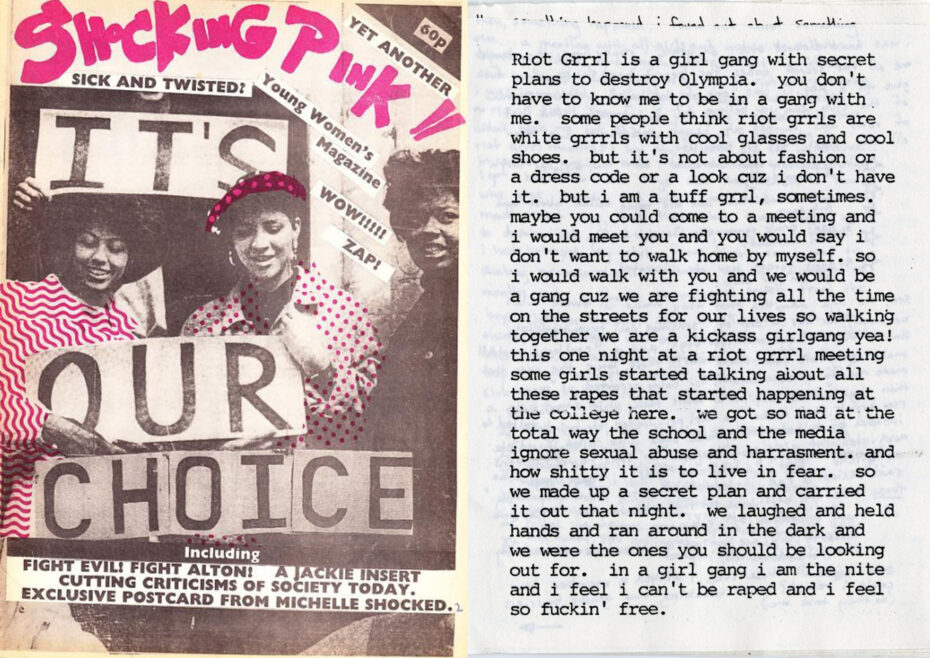

The zine would make its break from intergalactic geekdom in the 1960s when activism and the underground press became a popular tool to spread information for the counterculture. Before forums, social media and internet blogs, isolated factions, groups, and left-leaning individuals had to have a means of communication that wasn’t influenced by agenda-ridden media. The civil rights and feminist movements would benefit from an underground press that was self-produced and this would have an influence on the world of the zine, showing a youth movement that a message could be channeled without the use of a self-governing platform.

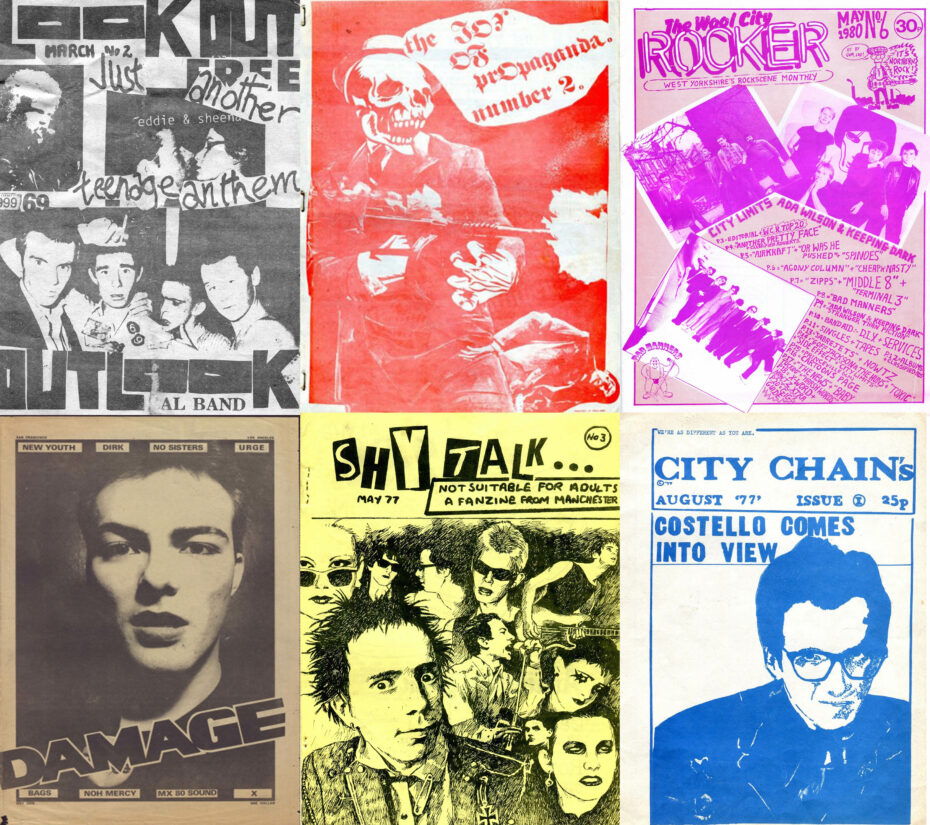

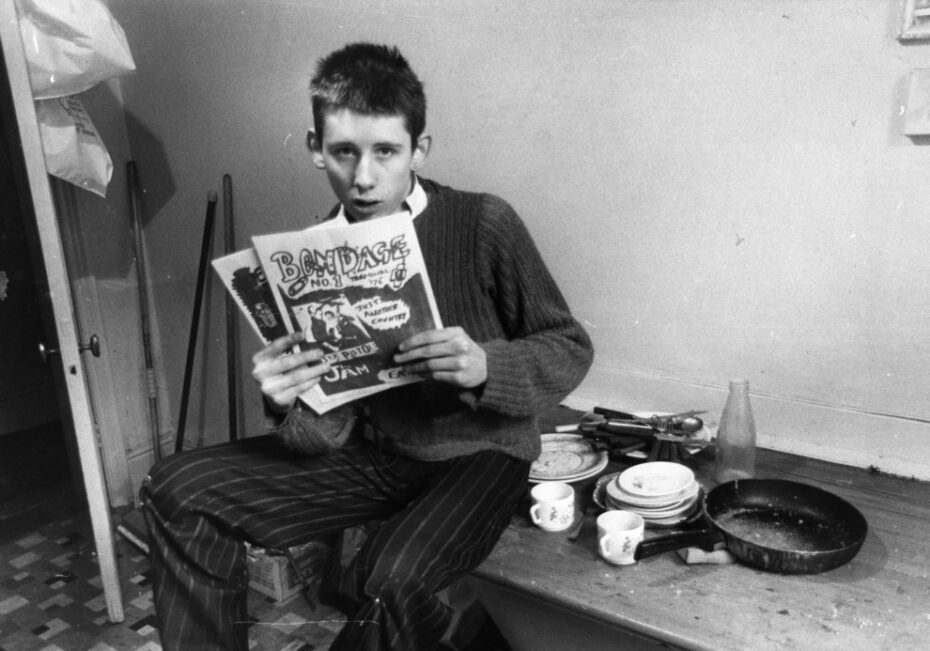

It was the 1970s that saw an explosion in the production of zines when the punk movement arrived like a meteor from outer space to destroy the dinosaurs of music and cultural stagnation. The zine would become the underground messenger of change. Electronic wizardry had produced a cumbersome unit called a photocopier that would now let the zinester duplicate their publication easily and cheaply.

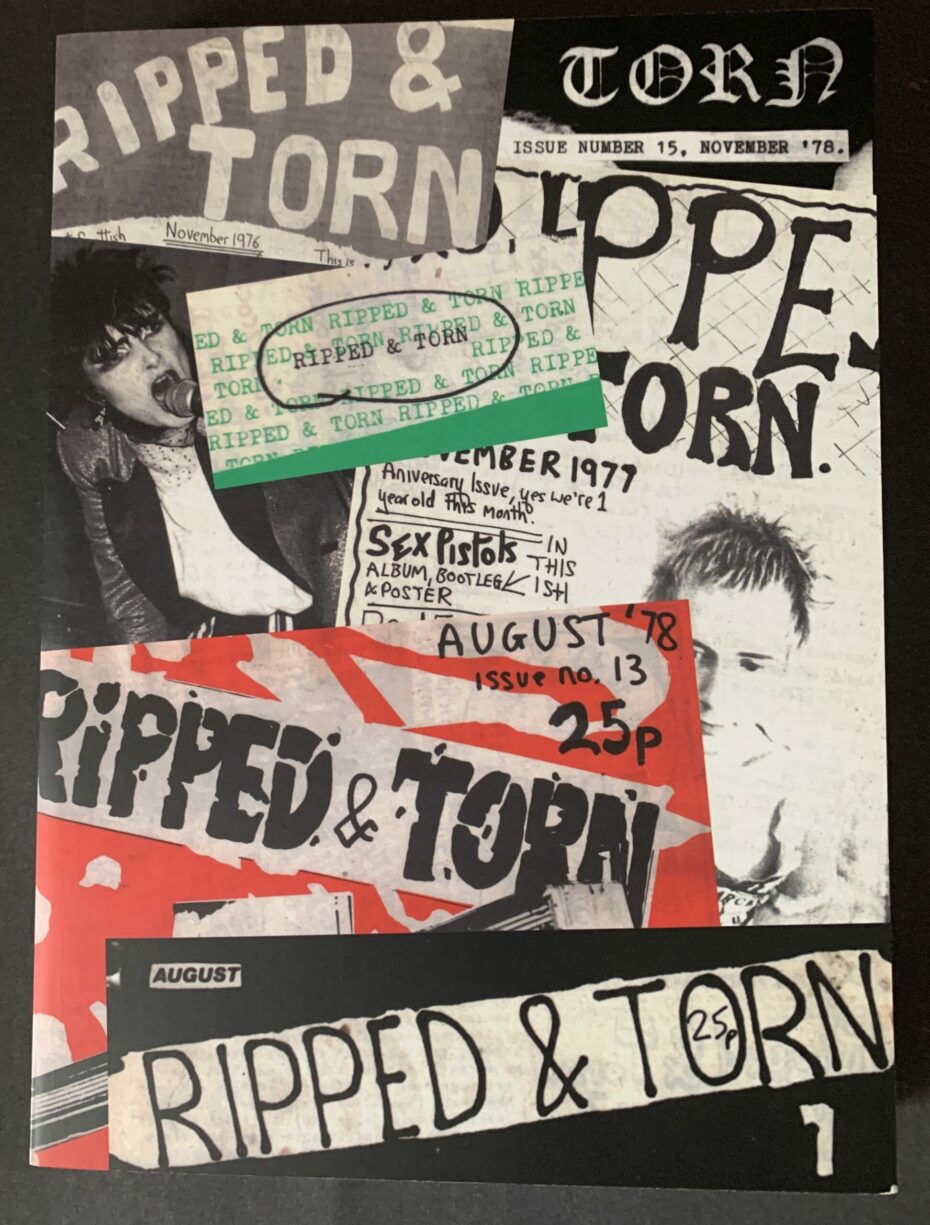

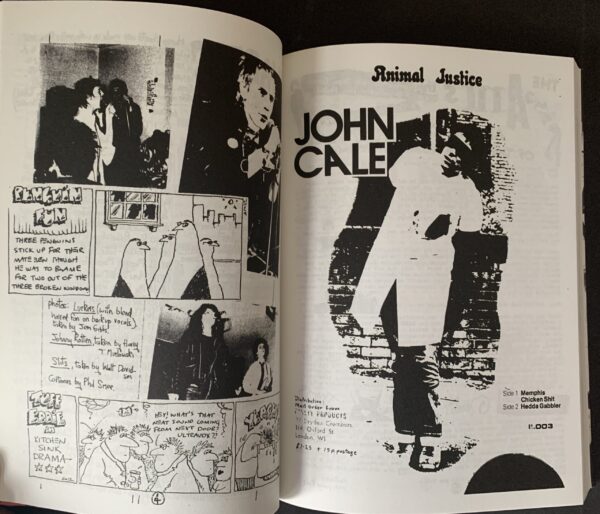

As copy shops sprang up around the Western world, so did new zines. In London, after watching the Ramones play at the Round House in 1976, a 19-year-old bank worker named Matt Perry went home and produced one of the first and most popular Punk zines: Sniffin’ Glue. It arrived at a time when the mass media was doing its best to ignore the punk scene and its raucous shock to their conservative sensibilities. Zines were the perfect place for the Punk movement to germinate, it fitted the punk ethos of DIY culture and anti-authoritarianism. Sniffin’ Glue went from a first run of 50 copies to 15,000 in a year and would document the first wave of punk through the eyes of the conspirators of the movement. It was a striking uncensored monochrome pamphlet devoid of an editor’s reproach that struck with a jagged urgency into the primed youth.

“Sniffin’ Glue was not so much badly written as barely written; grammar was non-existent, layout was haphazard, headlines were usually just written in felt tip, swearwords were often used in lieu of a reasoned argument. . .all of which gave Sniffin’ Glue its urgency and relevance.”

In America, there was Punk, started in 1976 by cartoonist John Holmstrom who documented the New York punk scene that revolved around the iconic lost venue CBGB’s. Fanzines and Zine’s would pop up for any new band until hundreds, if not thousands of new Zines would be circulating. Other prominent self-publications would include Ripped & Torn, Panache and Chainsaw

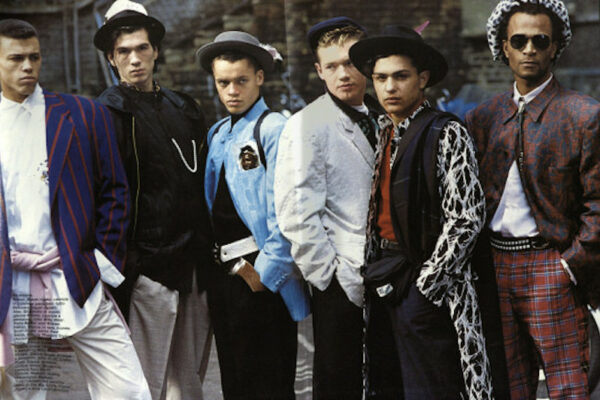

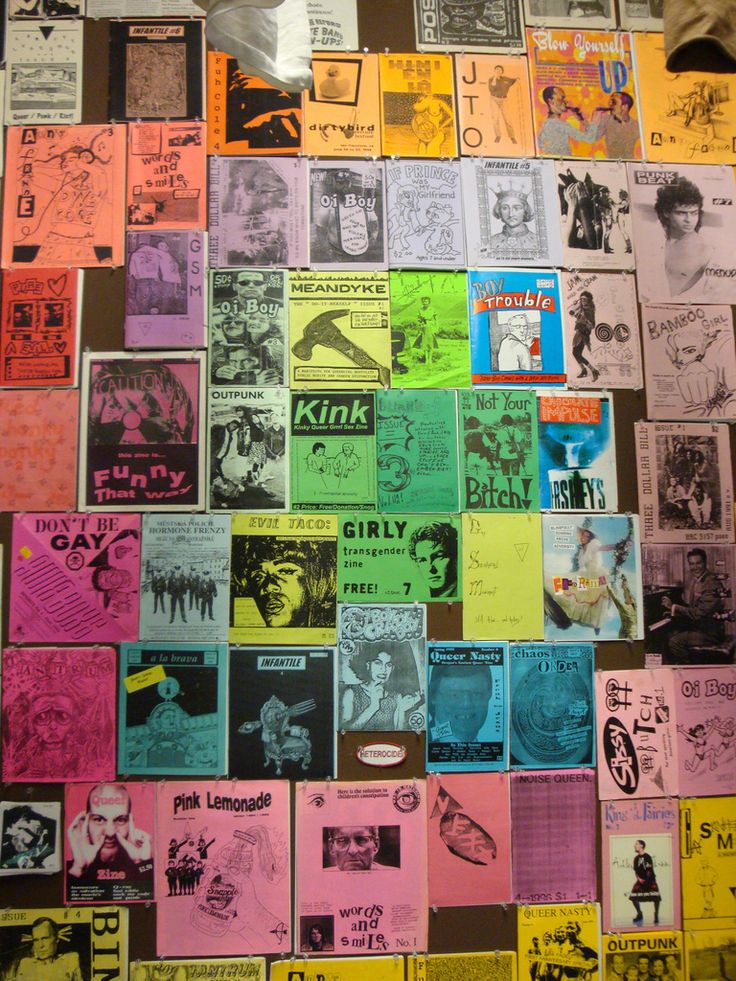

By the 1980s, zines were becoming a catalyst for other subcultures like Queercore. An offshoot of the punk movement, it gave the LGBTQ community a voice during a time of prejudice amongst its peers. Published in Canada, J.D.s was a queer punk zine that would run for six years and help establish the scene that eventually produced queercore bands, films, and art.

The 1982 – 1991 Zine Fact Sheet 5 attempted to categorise and review the massive circulation of zines. It held reviews, contact details, and information on the self-publishing scene that was evolving separately from mainstream culture.

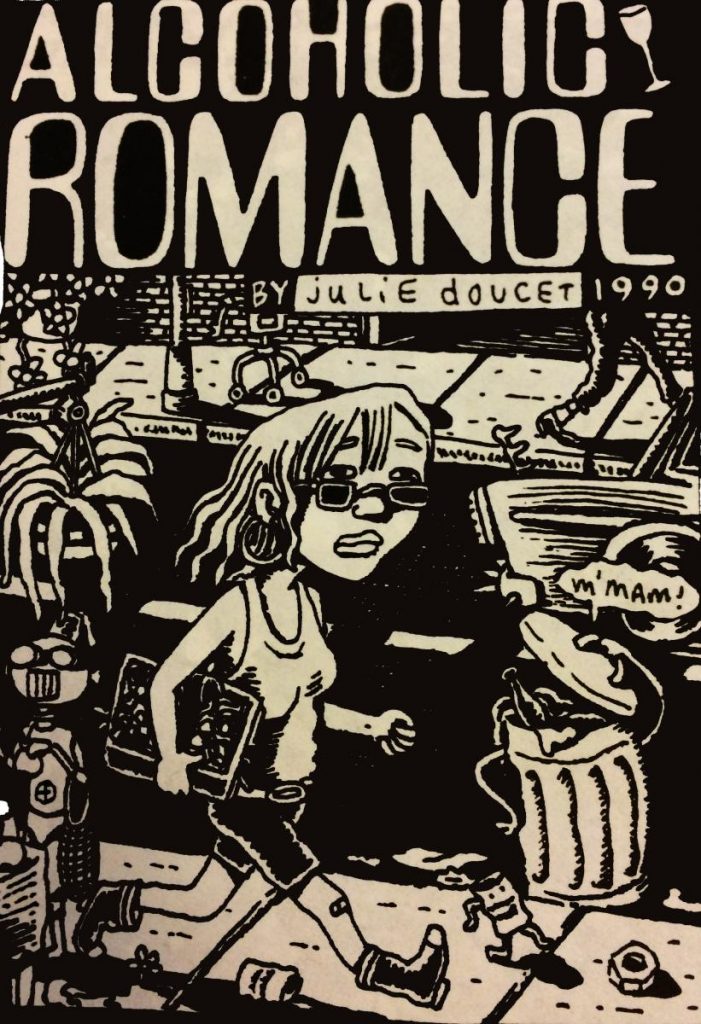

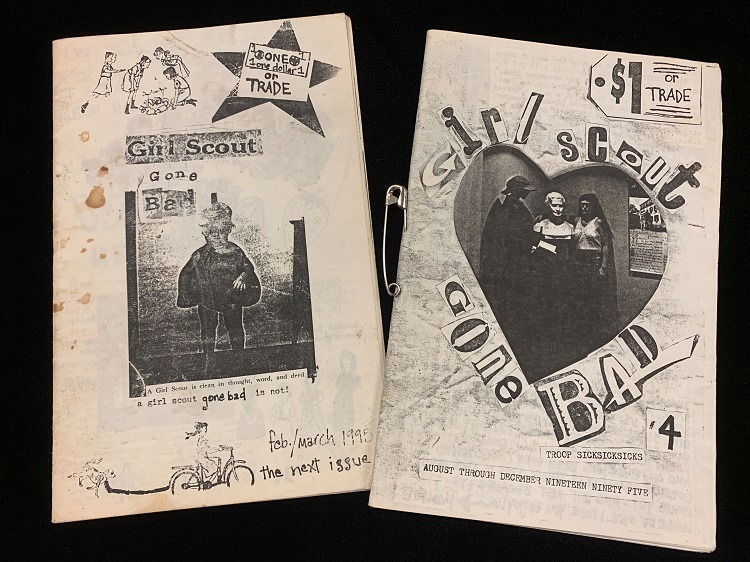

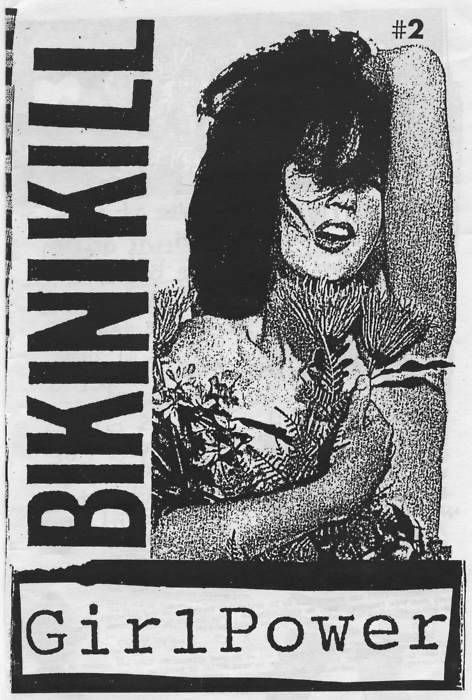

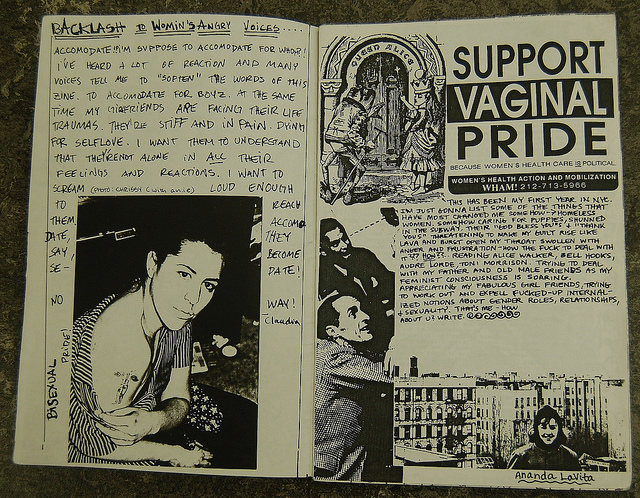

The 90s saw the emergence of the underground feminist Punk movement of Riot Grrrl and a surge in zines relating to it. A third wave of feminism, alongside the freedom of expression offered by the zine, let another generation tap into the social activism paved by the 1960s underground press. This Punk rock DIY apparatus was used again to ignite a cause and share in ideas and thoughts about social and political ideas. Zines like Jigsaw, Girl Germs, and Bikini Kill opened lines of communication not just about a cultural movement but about marginalised groups and a support system for women in the male-dominated music scene. By the mid-1990s, an estimated 40,000 Riot Grrrl zines were circulating in North America.

In the 2000s, the internet would have an impact on the production and popularity of the zine with many creators switching to online blogs and webpages. The ease and wider scope it offered would see many creators abandon their felt tip pens, scissors, and staplers for a laptop and a social media presence. But the zine wasn’t dead, it was just in hibernation, waiting for the next social cause or alternative thinking subculture to resurrect it from its monochromatic sleep.

Today the zine is going through something of a renaissance, with a politically energised youth movement rallying for change and a backlash against commercialism and mass marketing on digital platforms. Speaking to Zolima City Mag, archivist Elaine Lin explained why there’s currently a resurgence of underground press in Hong Kong, particularly in the form of zines. “The 2014 Umbrella Revolution protests … and resistance to the hegemony of land developers have been fertile ground for zine creators,” says Lin, and has seen it result in “a lot more zine groups like Zinecoop, zine festivals and even collaborations between zinesters, political activists and established organisations.” While zines can exist both online and on paper, the printed zine also finds a demand in a political climate where internet censorship is rife. Some are published under a pseudonym and distribution can be physical by the author, using a website (often Etsy) or they might go to zine swaps and shops. If the zine is part of a collective, they often have a printshop that has access to better materials and printing tools (although some say that takes away from the charm). Most people don’t get into zines for the money but video game-related zines have gained a strong economic presence in recent years, coming full circle and returning to those sci-fi roots.

An analog outlet for creativity and connection; something to share and keep to trade and pass on; the appeal of the zine will always be their uniqueness and inclusiveness; a vehicle for cultural resistance and a platform for expression. So if you have something to say, why not make a zine?