From the earliest colonial conflicts to the present day, the participation of Native American tribes and nations in American military campaigns spans a complex tapestry of alliances, conflicts, and shifting loyalties. But in our collective knowledge, so much of it is simply history unaccounted for. When we’re taught about that time America nearly split in two, at what point in the curriculum does it explain where Native Americans stood when they found themselves in the middle of a civil war over the enslavement of Black people? Just two decades after being forced to relocate from their own ancestral land en masse, surely it wasn’t their fight – or was it? Roughly twenty thousand American Indian soldiers fought on either side of the American Civil War and records show that many more Natives sided with the Confederacy. Why? The answers may surprise you.

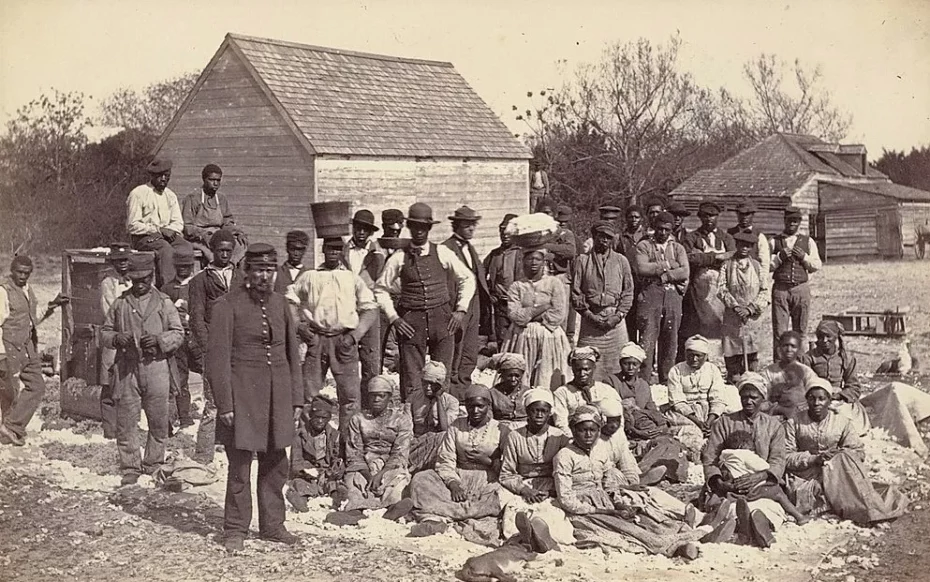

When in a position of desperation, enlisting with the employer that either pays more or promises less harm, makes enough sense – and this is exactly what many Native Americans soldiers did. Having been ethnically cleansed from their lands, many members of tribes such as Choctaw, Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Chickasaw, and Seminole Nations, were promised treaties by the Confederate army that guaranteed lands to be returned West of the Mississippi River. Meanwhile, the Natives who supported the Union hoped for general recognition of treaties and land rights. Wealthier tribe members however, particularly within the Cherokee elite, saw an opportunity for alliances with the anti-abolitionist Confederacy because they too, were owners of Black slaves.

There is a largely untold story of Native Americans who owned slaves, a twisted and little-known chapter in the long history of Indigenous American assimilation under the encroachment of Euro-American settlers; a reminder of “the complexity of colonialism, exploitation and victimisation that laid the foundations of our country,” writes Alaina E Roberts, Assistant Professor of History at the University of Pittsburgh.

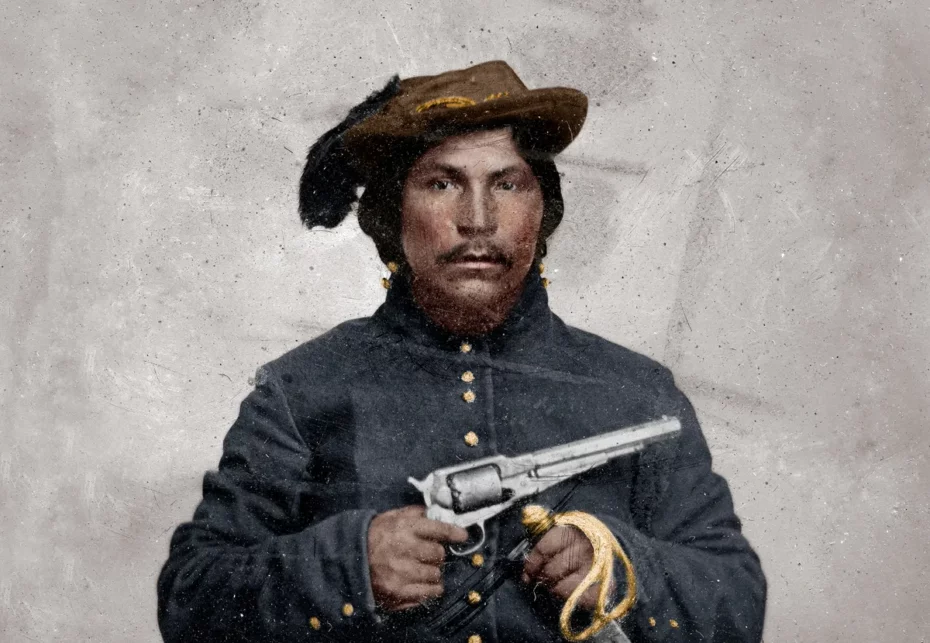

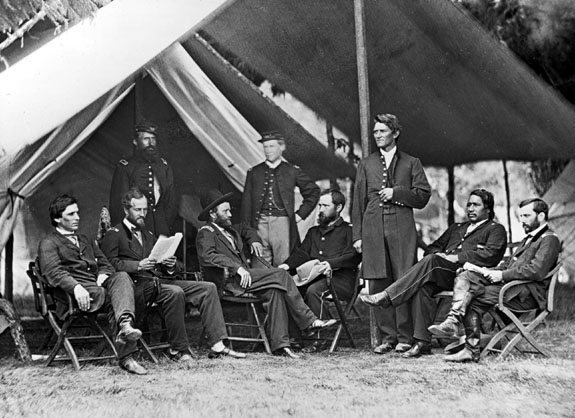

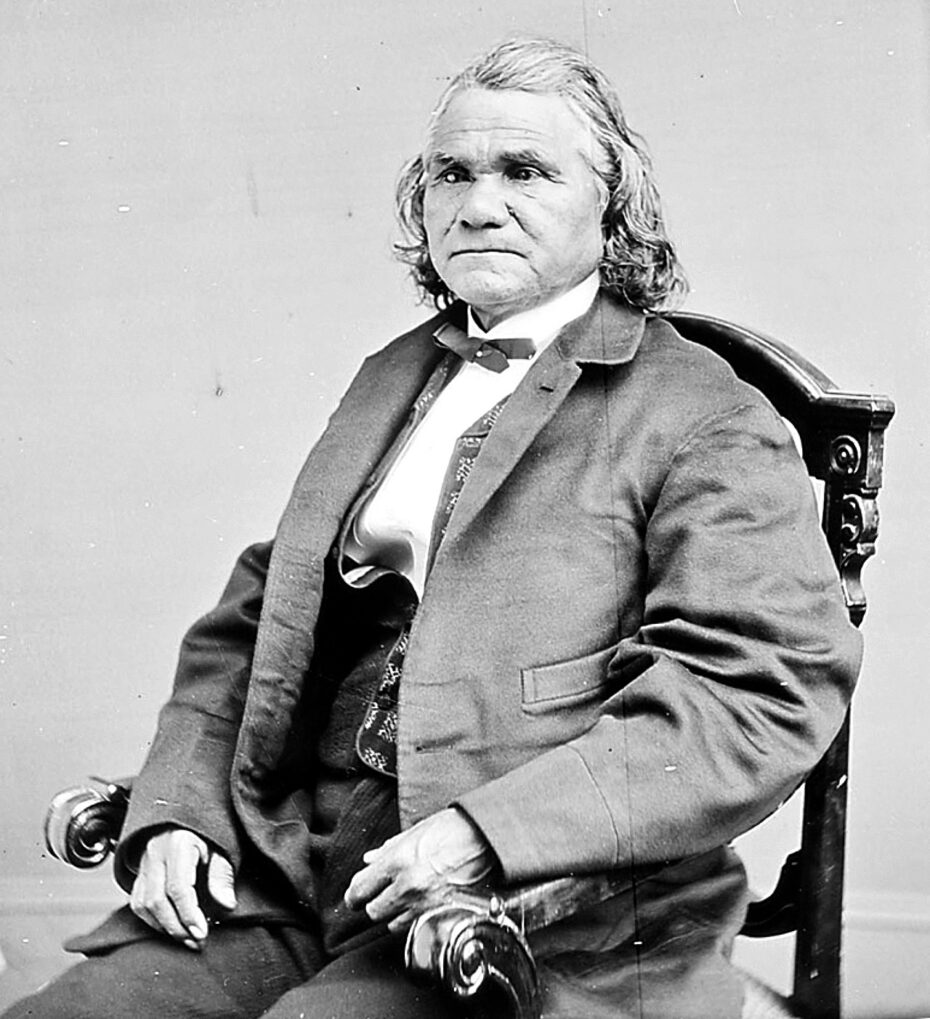

Among the most well-known Native American soldiers for the Civil War was one Brigadier General Ely S. Parker, a Tonawanda Seneca and close aide to Union General Ulysses S. Grant, who wrote the final draft of the Confederate surrender terms at Appomattox in Virginia that ended the war. According to Parker, as the Confederate General Roert E Lee agreed to surrender, “He extended his hand and said, ‘I am glad to see one real American here.’ I shook his hand and said, ‘We are all Americans.'” Years earlier, when Parker had initially tried to enlist for the Union Army as an engineer, he was denied and told that as an Indianm he could not join. After the war, when General Grant became President, he appointed Parker as Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

There was also Brigadier General Stand Watie, a Cherokee, who was the last of the Confederate generals to cease fighting after the surrender was concluded. His father was a full-blood Cherokee but also a wealthy planter, who held African-American slaves as laborers.

Even as 60,000 people of the “Five Civilized Tribes” were being ethnically cleansed and forcibly removed from their original lands to Indian Territory by the federal government, Cherokee slaveowners took their slaves with them on what became known as “the Trail of Tears” between 1830 and 1850.

“I used to like history,” said Paul Chaat Smith (Comanche), curator of the National Museum of the American Indian, who compared the often ugly truths of history to a “mangy, snarling dog standing between you and a crowd-pleasing narrative … Most of the time, history and I are frenemies at best.”

Just over 7% of Cherokee families were known to have owned slaves during the Antebellum period, although many Natives also supported the Confederacy out of fear that the Federal government would create a State out of what was then majority “Indian Territory”. For the Cherokee, that territory would indeed later become the State of Oklahoma.

The Cherokee Nation had their own slave codes and laws for Black slaves and freedmen after the war. With few differences to the discriminatory practices introduced by European-Americans, these laws prohibited people of African descent from voting, holding office, marrying Cherokee citizens and being taught to read or write, with lashings as a common form of punishment. To this day, the Nation is still grappling with the effects of a drawn-out ongoing controversy of the descendants of Cherokee Freedmen (African American slaves) seeking equal rights and tribal membership from the Cherokee Nation. In 2017, the U.S. District Court ruled in favor of the Freedmen descendants, granting full rights to citizenship in the Cherokee Nation.

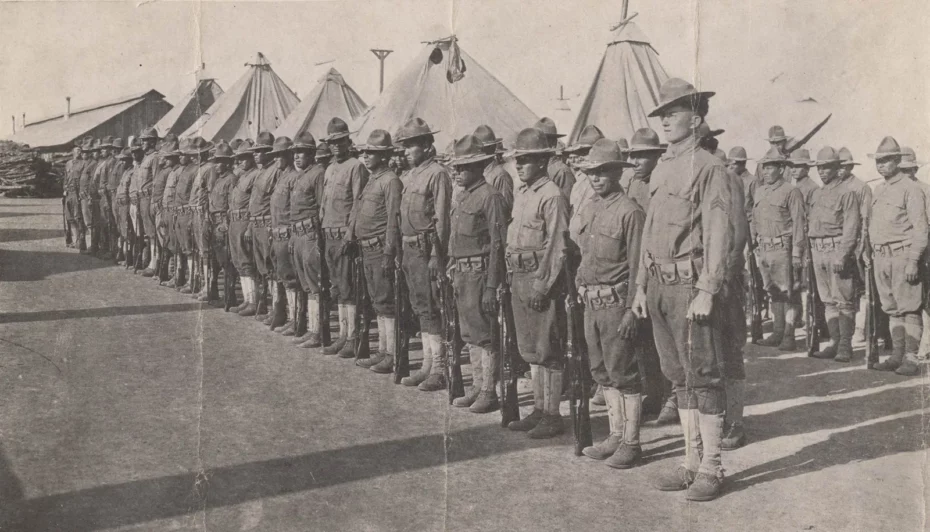

World War One saw over 8,000 Native American soldiers joining the US military’s ranks, 6,000 of whom volunteered for their service. The reason for such a mass enrolment? The desire for American citizenship and recognition. About a third of the Native American population still had not received citizenship. Many of these soldiers fought on the front lines and were subject to “scientific racism.” William C. Meadows, an expert on the subject, and professor at Missouri State University states that Native American soldiers were exposed to more highly dangerous aspects of battle in comparison to that of other races or ethnic backgrounds.

American Natives joined the military once again in WWII, this time to escape the throws of poverty, while still seeking freedom within their own land. Lewis Naranjo of Santa Clara Pueblo said, “We are doing our best to win the war to be free from danger as much as the white man. We are fighting with Uncle Sam’s army to defend the right of our people to live our own life in our own way.” Another service member, Marge Pascale of the Ojibwe tribe and a member of the Women’s Army Corps said, “One thing about Service, you get two pairs of shoes and you get a bed and you get to eat.”

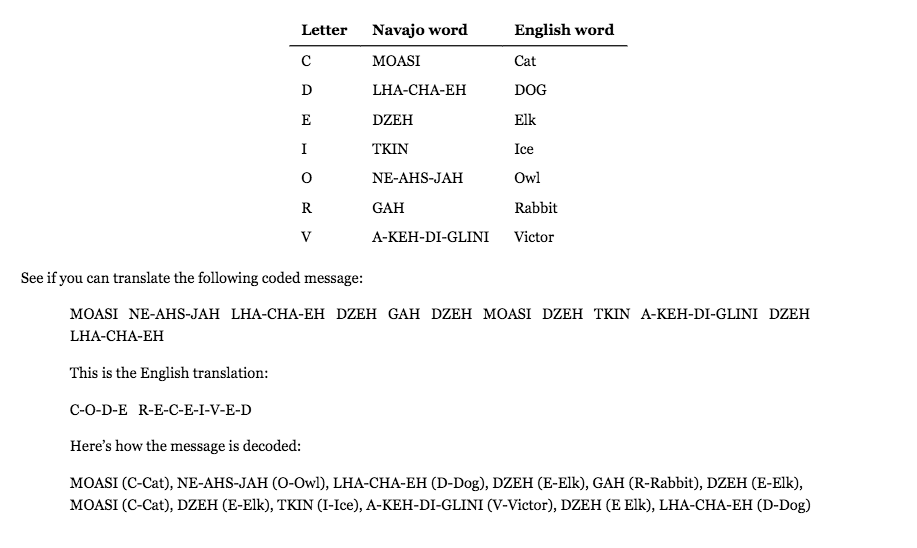

But when it came to winning WWII, there was one particularly powerful weapon used by the United States; the rich, complex language of the Navajo people, which became an invaluable code used by soldiers to puzzle even the cleverest of enemy minds. Of course, this was the very same language they had been forbidden to speak at home for so long during the forced cultural assimilation and cultural genocide of Native Americans that lasted well into the 20th century at the hands of the US government.

The Navajo language was a verbal, rarely-written language and without a razor sharp pronunciation of its words, was simply incomprehensible. “It was a double-edged sword,” explains historian Peter Iverson, “it gave it a kind of complexity in how it was spoken that in English we don’t have. We can speak English very sloppily and still be understood.”

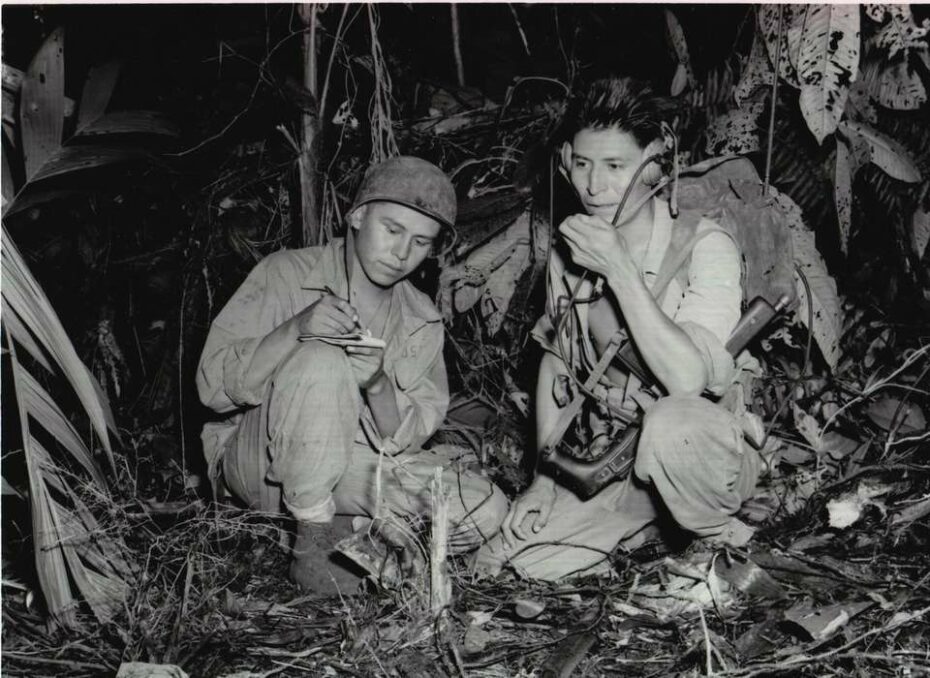

Native American code talking had already been implemented in WWI with the aid of the Cherokee and Choctaw peoples, and WWII saw the recruitment of nearly 500 bilingual Navajos into the U.S. Marines Corps to serve in communications units in the Pacific. It all started at the suggestion of civil engineer Philip Johnston, who was raised on a Navajo reservation and new the language well.

Staged tests proved that Navajo men were capable of encoding, transmitting, and decoding English messages in a mere 20 seconds. They were lightyears faster than the machines, which took around 30 minutes.

Words like atsá, which literally meant “eagle,” were soon understood as “transport plane.” Gini, or “chicken hawk,” meant there was a “dive plane,” and the presence of a lieutenant colonel was communicated with the words for “silver oak leaf.” Wanna have a crack it? Go ahead:

Code Talkers memorised 17 pages of code in training. In battle, there was no room for error when it came to transmitting messages. “Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima,” explained signal officer Howard Connor. Indeed, it was during that pivotal time that six particular Navajo men worked non-stop to communicate over 800 messages in two days — each one without a single error.

But it was more than the language itself, says a former Code Talker Sam Billison, that made the men such incredible soldiers. “The Navajo culture taught you to be aware, ready,” and in touch with your environment. When asked by his fellow soldiers as to why he fought for the government that had oppressed his people, he only explained, “We still think of North America as our country…War experience is so dirty,” he concludes, “and so humbling. You don’t forget these things.”

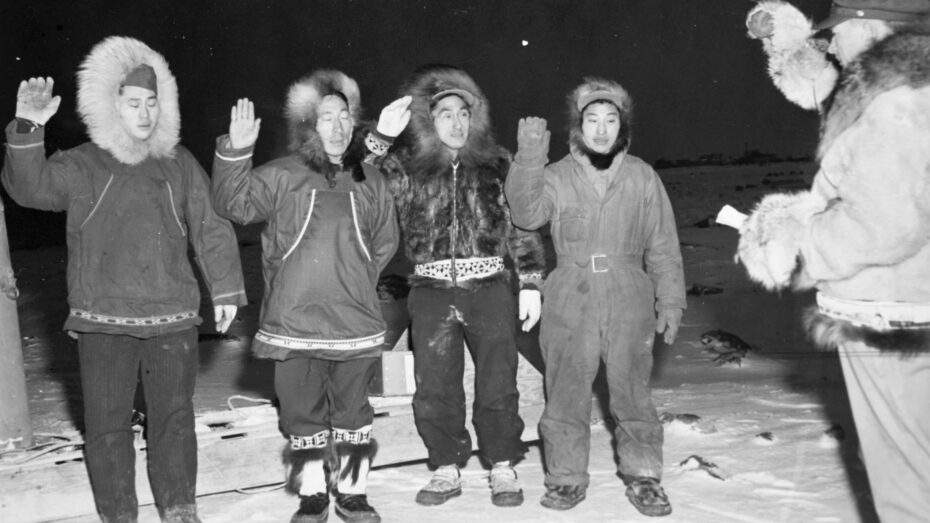

When the Second World War ended, members of Alaska’s armed forces rallied to end segregation. They were successful in making way for the birth of Alaska’s first anti discrimination law, however it would take sixty years – until 2010 – before the United States government would honor the Alaskan Natives for their service.

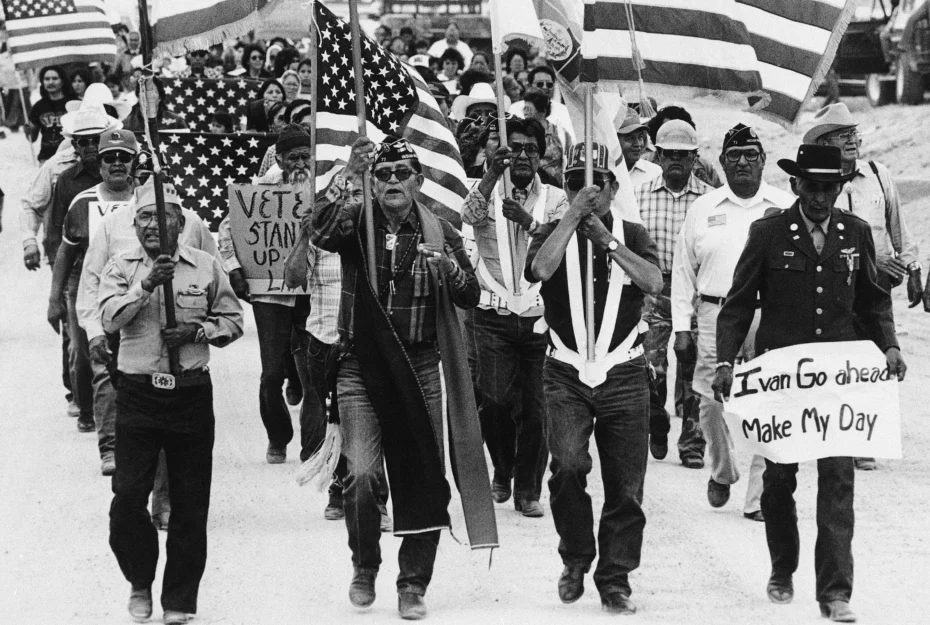

The role of Indigenous Americans in World War II is rarely remembered in the history books and their forgotten contribution and lack of portrayal as the American war hero is yet another reminder of the systematic repression of their people and history. During the Vietnam War, some Native soldiers saw similarities between the war “fought by whites against their ancestors”, describing it as similar to how the American soldiers were relocating entire Vietnamese village populations. According to Time Magazine, “Since 9/11, Native Americans have served in the U.S. military at higher rates than other ethnic groups. Today there are about 31,000 American Indian and Alaska Native men and women classified as active duty in the U.S. military, along with 140,000 living veterans.”

We’ll keep coming back to this quote until it stops feeling relevant:

“We often think of peace as the absence of war, that if powerful countries would reduce their weapon arsenals, we could have peace. But if we look deeply into the weapons, we see our own minds – our own prejudices, fears and ignorance. Even if we transport all the bombs to the moon, the roots of war and the roots of bombs are still there, in our hearts and minds, and sooner or later we will make new bombs. To work for peace is to uproot war from ourselves and from the hearts of men and women. To prepare for war, to give millions of men and women the opportunity to practice killing day and night in their hearts, is to plant millions of seeds of violence, anger, frustration, and fear that will be passed on for generations to come.”

– Thich Nhat Hanh, Vietnamese monk and peace activist.