What do Elvis, President John F. Kennedy (and Jackie), Alfred Hitchcock, Truman Capote, Marlene Dietrich and Marilyn Monroe all have in common? Apart from the obvious cultural and historical significance, they all shared a special relationship with Dr. Max Jacobson or as he would later become known, ‘Dr. Feelgood’. Private physician to the rich and powerful, Dr. Jacobson would administer his own brand of alternative medicine with an efficacious bedside manner, a questionable ethical morality, and a surgical bag full of illicit concoctions known as “vitamin shots”. Jacobson would insert himself into the lives of the American glitterati and practice his own unique style of personal medicine with grave consequences to their careers and wellbeing, but also by extension, to the American people. It’s an unnerving and little-known truth that when JFK was president, he was pretty much high throughout most of the Cold War.

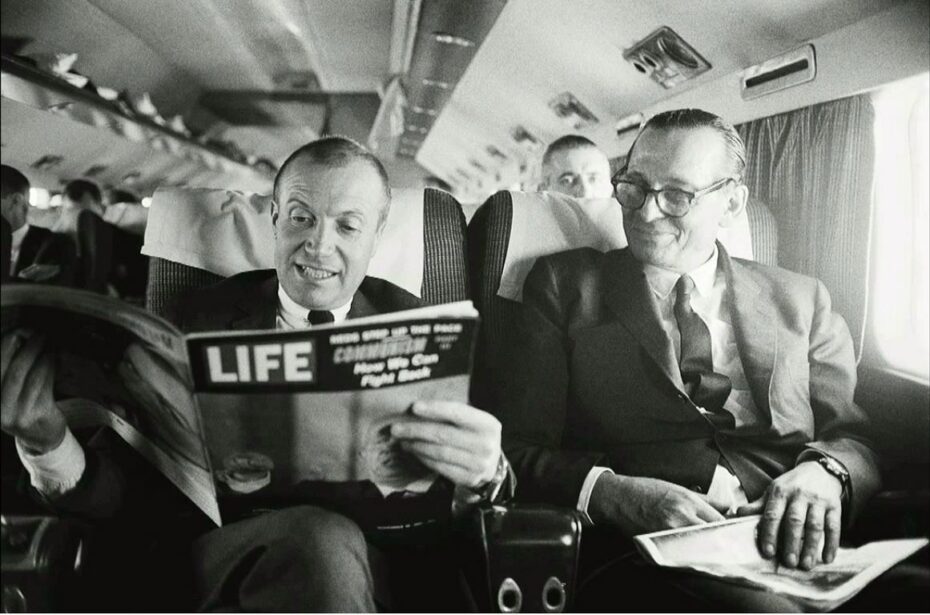

In 1961, President Kennedy sat down with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in what would become one of the defining meetings of the Cold War era. Lurking in the background would be Dr. Max Jacobson, JFK’s then personal physician. The summit in Vienna between arguably the two most powerful men in the world would not go well. Kennedy, suffering from a series of medical problems, had formed a relationship with Dr. Jacobson in 1960 and was now getting regular doses of Jacobson’s ‘miracle cure’; his very own elixir of life pumped straight into the veins of the US president. Some would later blame Kennedy’s performance in this crucial global summit on the substances he was administered by Jacobson, and eventually, the president would be convinced to stop seeking his personal Panacea by his own orthopaedic surgeon, who had threatened to expose him. By May 1962, Jacobson had visited the White House a total of thirty-four times. But just how did this dubious clinician form a client list of some of the most famous figures of the era?

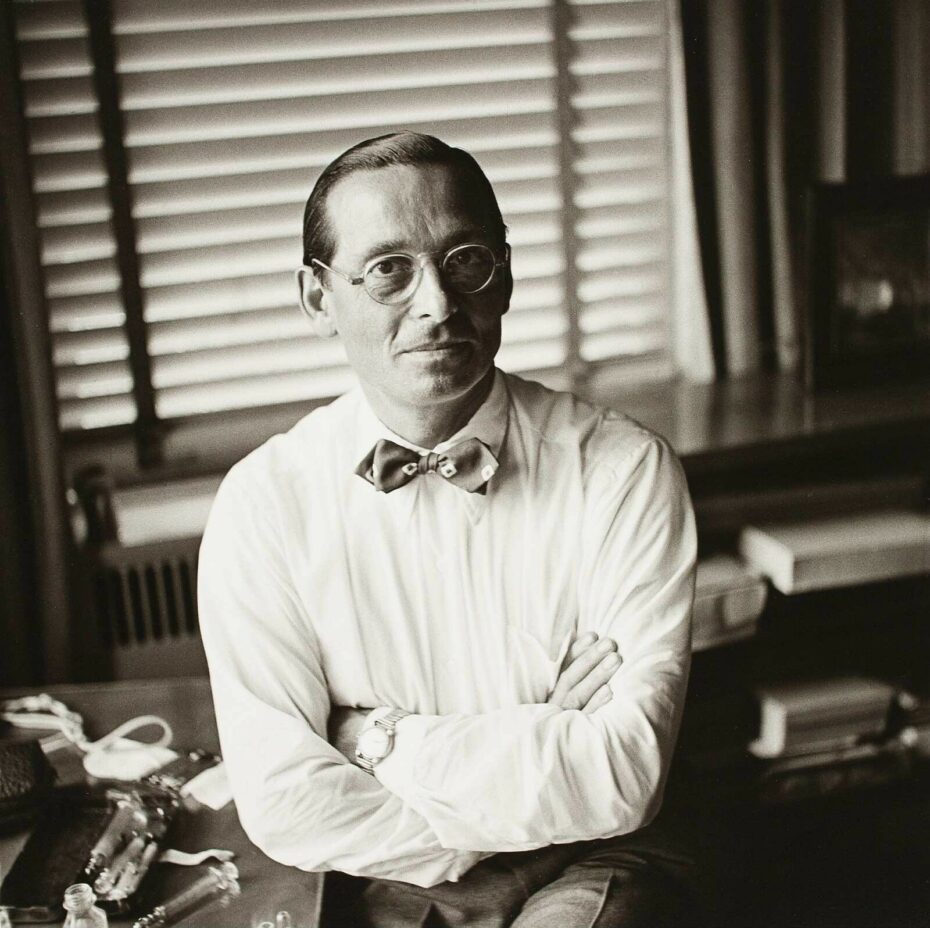

Born in Germany in 1900, Max Jacobson would gain his medical degree from the University of Berlin before fleeing Nazi oppression in 1936. He would eventually settle in New York’s Manhattan where he started his medical practice. Early on in Jacobson’s career, he was known for his unorthodox approach to medicine. His initial goals were to find a cure for cancer and multiple sclerosis with something he was calling, ’tissue regeneration therapy’. Little is known about his initial experiments or progress with his medical investigations, but what is apparent, is that after his discovery of the recently synthesised amphetamine sulfate, his medical trials hit new highs.

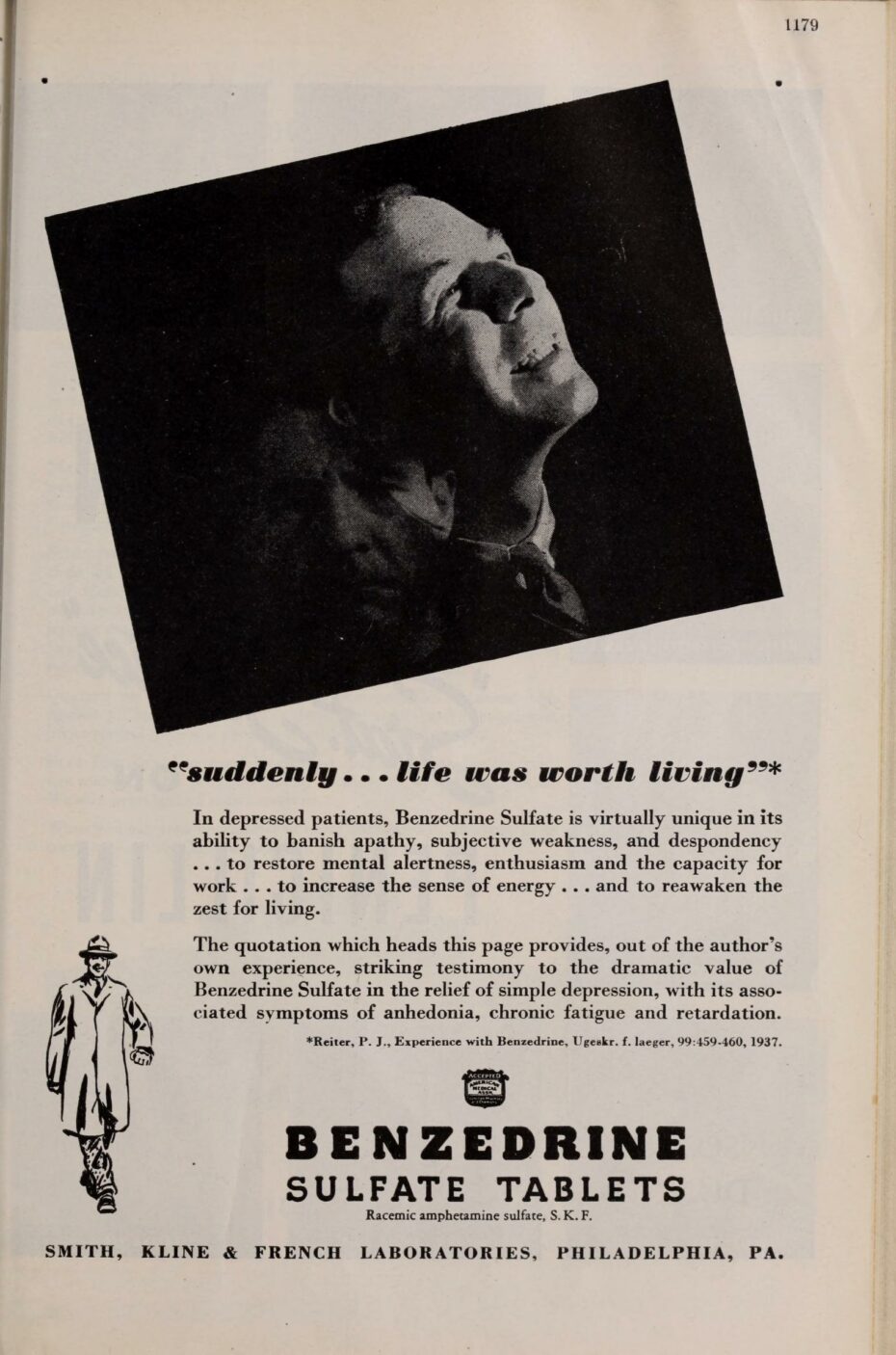

Amphetamine was first discovered in the late 19th century, but its use in World War II by both the Allies and the German army had seen its production escalate, with an estimated 200 million amphetamine tablets being administered to troops on both sides. Even Hitler had his own personal physician on hand, ready to give him ‘the good stuff’. By 1937, doctors in America were prescribing the pharmaceutical variant Benzedrine sulfate for a variety of ailments.

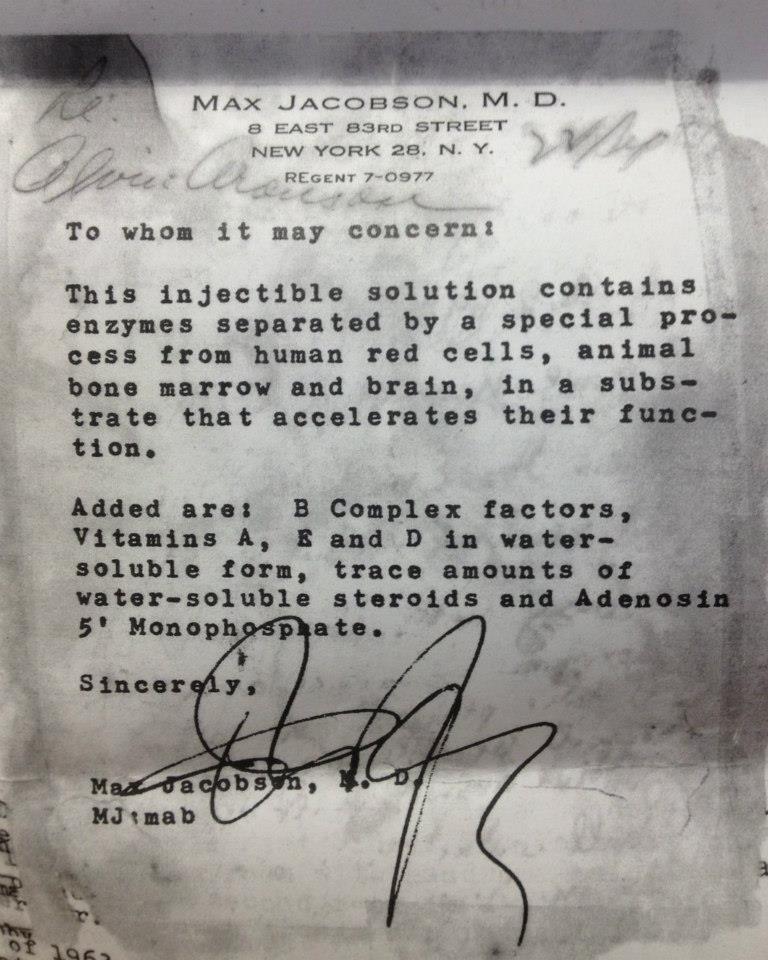

Jacobson had found the base for his wonder drug. He began experimenting with concoctions of amphetamines, animal hormones, bone marrow, enzymes, painkillers, steroids, multivitamins, and even human placenta. Naturally, he felt it prudent to test his experimental tonics first by mainlining the go juice himself – getting high on his own supply would later become part of Dr. Jacobson’s everyday practice. By the 1940s, many Broadway actors directors and dancers had become devotees of Jacobson’s Miracle shots. Word was spreading that there was a doctor in Manhattan who was sympathetic to the needs of the showbiz fraternity, their long hours and gruelling schedules. Jacobson’s name was passed on from one person to the next, in a conspiratorial tête-à-tête, with endorsements from leading figures in show business. Soon Jacobson’s offices were full of people wanting his ‘feelgood’ cure. His patients described the scene of a doctor resembling a mad professor darting from one room to the other dishing out shots from a syringe to as many as 40 people waiting to be seen. It seems Jacobson wasn’t picky about the status of his patients, he considered everyone had the right to try his cure for melancholy, and he would administer his shots day and night.

By the 1950s, New York was hooked, quite literally, on Dr. Jacobson’s vials of happiness. It was later found in a 5 year period that 40lbs worth of amphetamines had been ordered by Jacobson, enough for thousands of shots. Some of his famous patients now included Alfred Hitchcock, Marlene Dietrich, Elizabeth Taylor, Betty Davis, Tennessee Williams, and Judy Garland. After Tennessee Williams introduced Truman Capote to Miracle Max, as he was now being called, he described it as: “instant euphoria. You feel like Superman. You’re flying. Ideas come at the speed of light. You go seventy-two hours straight without so much as a coffee break. You don’t need sleep, you don’t need nourishment. If it’s sex you’re after, you go all night. Then you crash — it’s like falling down a well, like parachuting without a parachute. You want to hold onto something and there’s nothing out there but air.”

Singers like Andy Williams, Frank Sinatra, and Eddie Fischer all went to Dr. Max for help with performance and their ailing voices and Fischer would later say that this would be the start of his 37-year addiction to amphetamines. Jacobson had created the market and the need, so much need in fact, that he’d started letting his patients inject themselves. After a few brief instructions from his nursing staff, they were let loose with a syringe and his special cocktail of sunshine. Jacobson had even begun to ship his unlicensed, self-made product worldwide from his offices. The vials held no label or active pharmaceutical ingredient lists, and if any of his patients were to ask, they were reassured that as long as they were feeling better, that’s all they needed to know. Jacobson’s ‘experiments’ had become by this time, even more eccentric. He’d taken to adding eel cells to his formulae and small stones at the bottom of the vials which he identified as Uranium, “to give the liquid, energy”

And as every high has a low and every up has a down, the results of prolonged use of amphetamines had disastrous consequences. Dr. Max Jacobson’s party was coming to an end. The crash was close and Dr. Feelgood’s clientele were not feeling so good anymore. He’d been blacklisted by President Kennedy’s Secret Service detail, the very people who had given him his moniker of Dr. Feelgood. In 1961, in a New York hotel, after one too many of Miracle Max’s shots, President Kennedy had allegedly experienced a psychotic break, stripping naked and charging around first his room and then the corridors of the hotel. The Secret Service intervened, Jacobson was called and the President was given something to calm him. In the sports world, Mickey Mantle, the legendary baseball player for the New York Yankees had been hospitalised after receiving a shot from Jacobson, putting an end to his 61 ‘World Series’ and hopes of beating Babe Ruth’s home run record.

Lawsuits and more bad reactions followed, and then in 1969, former presidential photographer Mark Shaw was found dead in his apartment from acute amphetamine poisoning. Shaw’s arms were covered in track marks and at his apartment, countless vials of Max’s medication were found. After a long investigation and a court case where several prominent figures testified for and against Jacobson, he was eventually stripped of his medical license in 1975. He was labeled as a fraud and a charlatan by some and a yet still, a caring creative and futurist by others. Jacobson’s real intent may be harder to discover. For someone who treated the famous, rich, and powerful, he led a modest life without fanfare. With a small apartment and a normal car, it was speculated that most of his famous clientele still owed him money from his 24-hour personal care and ‘treatments’. It would later be discovered that years earlier, he had spent most of his money helping families that had fled the Nazis all over Europe and sponsoring Jewish immigrants in the United States (Jacobsen himself was Jewish).

The paradoxical Dr. Max Jacobson bragged about his famous associations with the stars but also treated the ordinary patient. He would ignore ethical procedures, use unregulated unlicensed mixtures of drugs, and continue his research into cures for diseases and life-threatening conditions. Was Jacobson addicted to his patient’s dependency on him and his drugs or did he truly believe he was helping them? Max Jacobson would never regain his medical license and died from a heart attack in 1979.

When does a doctor’s Hippocratic Oath become secondary to the demands of the rich and famous? VIP medicine has become standard practice for the elite today, and in the world of stardom and sycophants, it continues to lead to an overwhelming number of celebrity deaths; Michael Jackson, Prince, Whitney Houston and Philip Seymour Hoffman to name a few, were all found to have taken a cocktail of prescription and illegal drugs at the time of their deaths. But the realities of celebrity culture, the desire for secrecy and privacy, as well as financial incentives for VIP doctors are the fatal ingredients that ultimately blur ethical boundaries.