Agnès Varda throughout her career was seen as belonging to the older generation. A pioneering photographer, writer, filmmaker and artist, at the beginning of her career and at barely 30 years old, she became known as the “grandmother of the New Wave.” But Varda was the cool kind of grandmother, the one with a thousand stories to tell, a genuine interest in people and a distinctive style that would always get her noticed.

Taking to Instagram as she approached her 90th birthday, Varda may not have made it into the algorithms that draw in the next generations, which is why we’ve decided to go old style by putting pen to paper and attempting to create a snackable, even TikTok friendly, list of curious and intriguing Varda facts here. Ya know, for sharing with future generations, or anyone who’s been wanting to familiarise themselves with Agnès for years, and just never got around to it. If you like the curious stories shared on MessyNessyChic, you’ll love Agnès Varda. And if you think Wes Anderson has an eye, wait until you see Varda’s.

Agnès ran away from home to take a job on a fishing boat

Agnès Varda was born in 1928 in Brussels, but at the age of 12 years old, with her Greek father, French mother and four other siblings, she fled the German invasion of Belgium to settle in Sète, France. At 18, Varda changed her name from Arlette to Agnès. Having received a degree in literature and psychology from the Sorbonne in Paris, she was unsure which direction she wanted her life to go in. Running away from home to work on a fishing boat in Corsica, Varda would come away from these three months deciding to be a photographer.

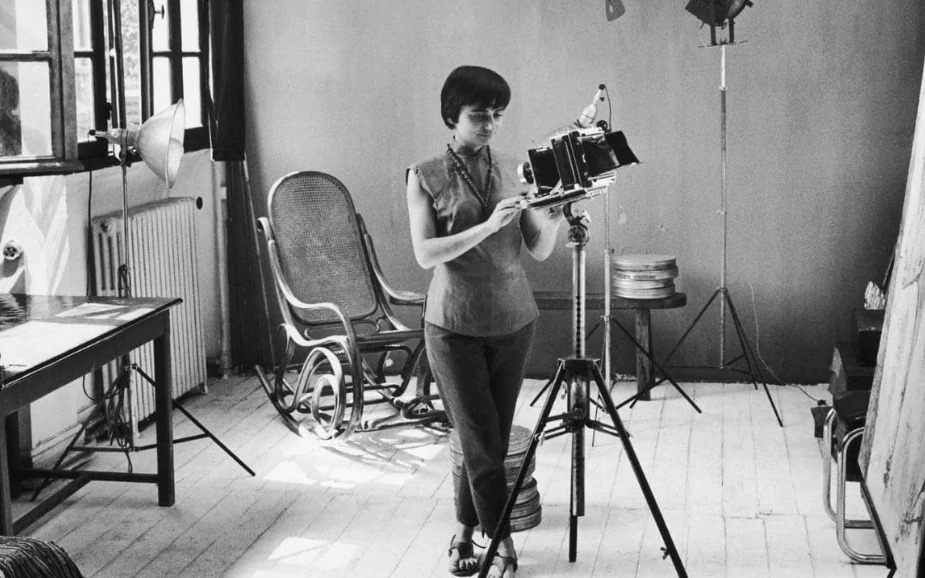

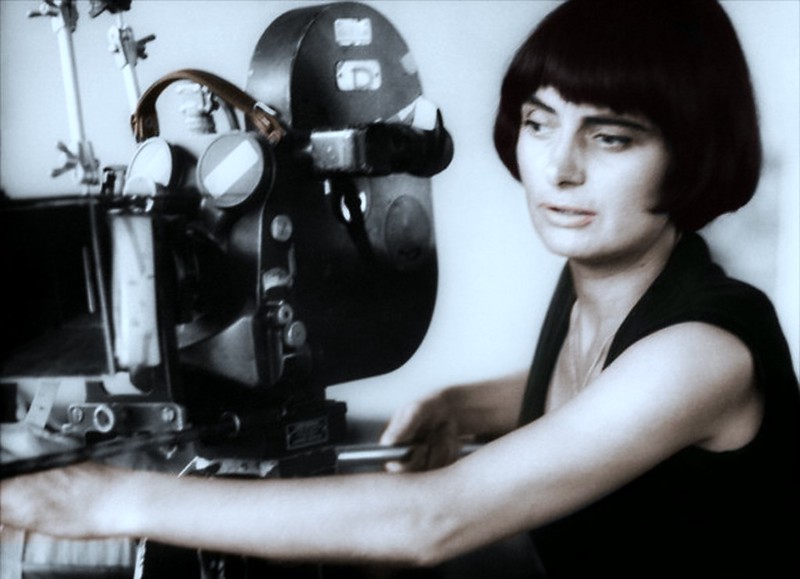

She was a “girlboss” way ahead of her time

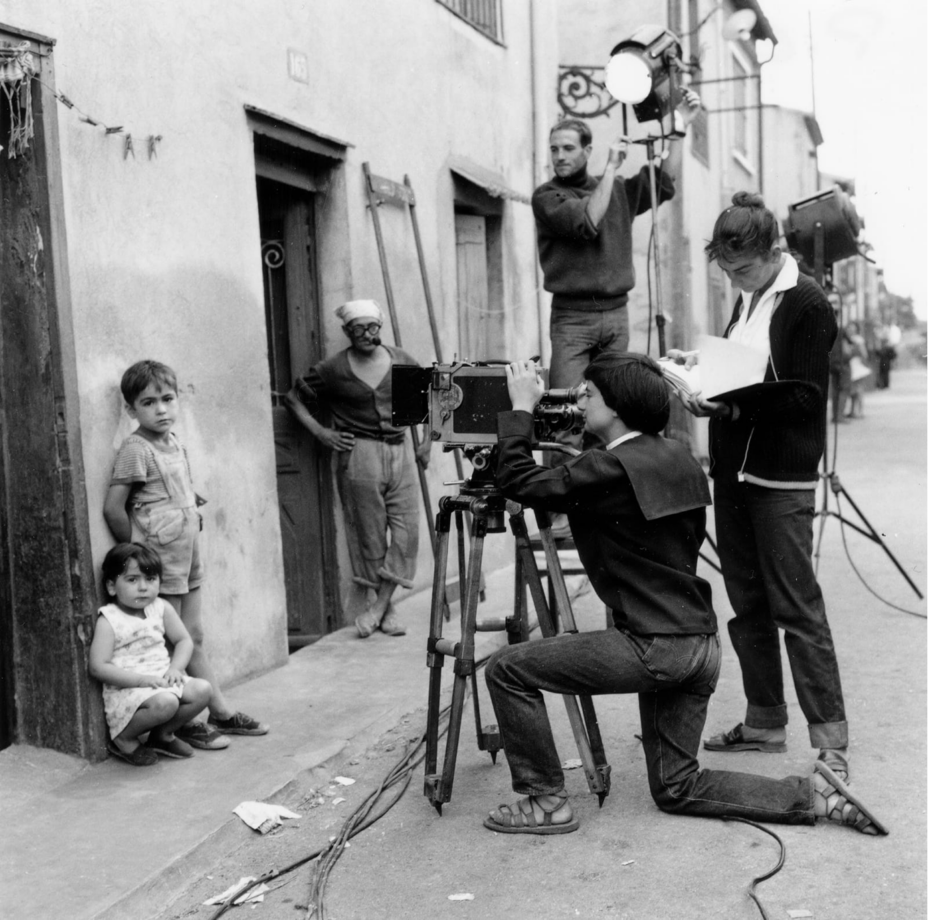

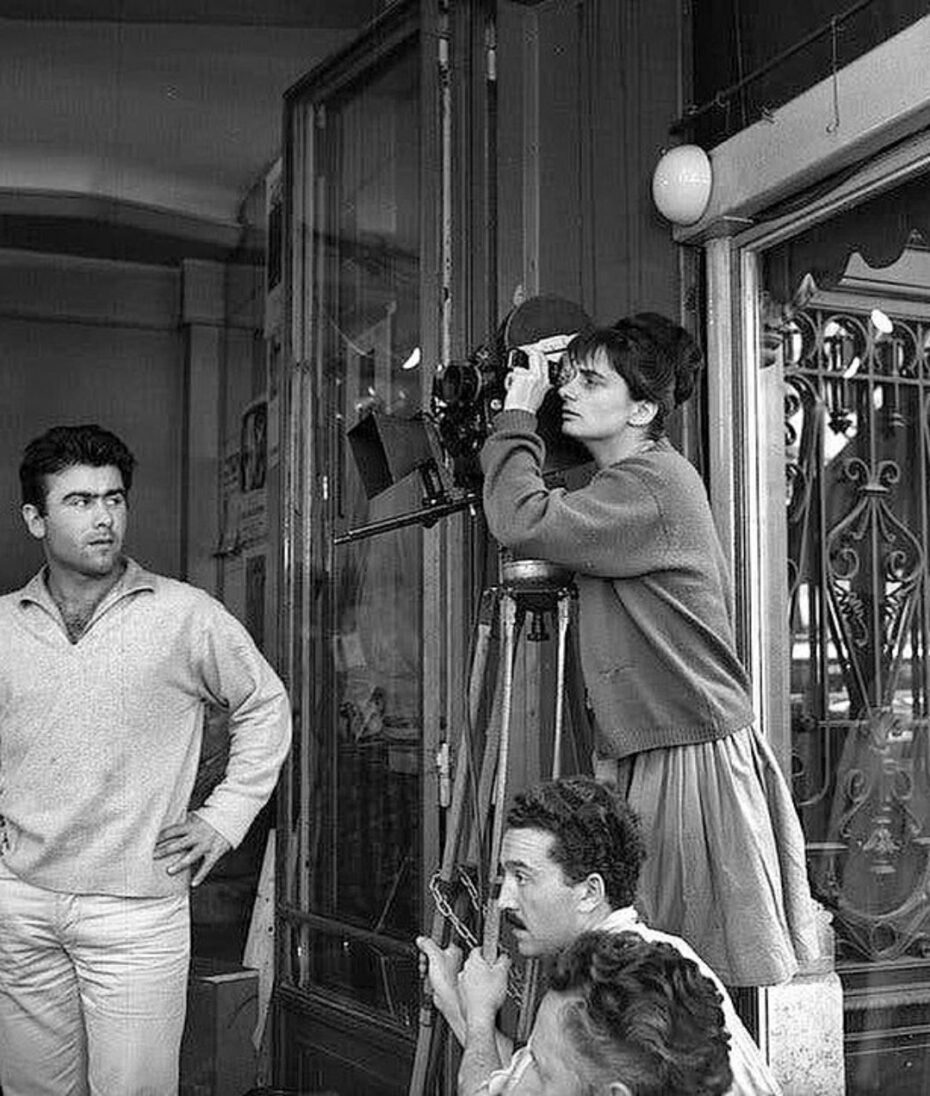

Agnès found work in Paris, working as a photographer for family and wedding photos until she was hired full-time by the Théâtre National Populaire. But soon she craved more from her work. Agnès was an observer. She loved nothing more than watching the ordinary lives of people around her, and although claiming to have seen hardly any films beforehand, decided that she wanted to become a filmmaker.

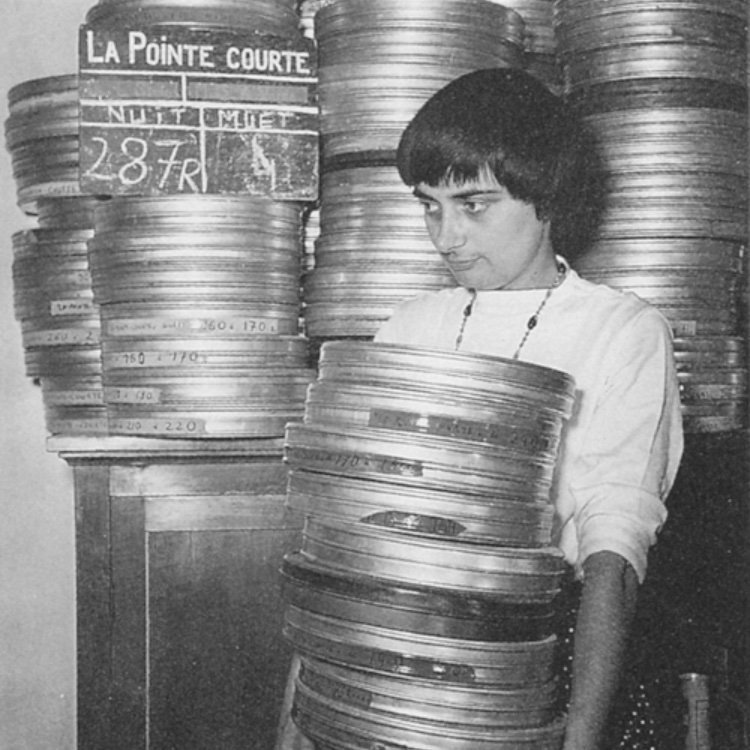

This however, was the mid-fifties and women simply didn’t make films. This didn’t put Varda off however, she just found a way around this by creating her own production company, Tamaris Films (which became Ciné Tamaris in 1977) in order to make her first film, La Pointe Courte. Financed through a small inheritance from her father, the film cost around 20 times less than films of the time.

The premise of La Pointe Courte was simple. A couple from Paris decide to spend some time in Pointe Courte (near Sète where Agnès spent much of her childhood) in order to decide if they were going to settle there for good or not. Varda however used the film to look more into the everyday lives of the people in the area. We see women gossiping, laundry being hung out and terse exchanges with a young fisherman and the inspectors. This was a film which celebrated Varda’s roots and helped pioneer the New Wave of French cinema, something Varda would only get credited for later in life and set a precedent for many other (male) filmmakers to start making films of this ilk.

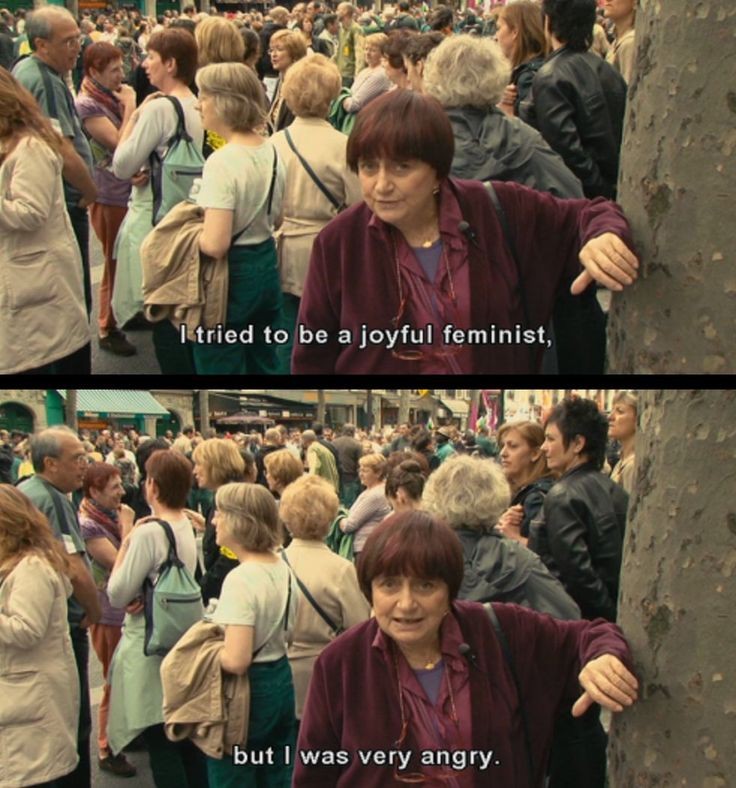

Varda was part of the 343 sluts

Varda referred to herself as a “feminist militant” and this fed into both her personal and professional life. In 1971 France, the Bobigny trial prosecuted Marie-Claire Chevalier, a 16-year-old girl for having an abortion, after being raped by one of her classmates. Her mother, the doctor that performed the abortion, and two of her friends were called to the stand and faced harsh prison sentences.

Reacting to the trial, Varda, along with 342 other women, including Simone de Beauvoir, signed a manifesto declaring, “We’ve had abortions. Judge us.” The manifesto was nicknamed ‘le manifeste des 343 salopes” (manifesto of 343 sluts) after a caricature appeared in French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. The 343 women who signed the manifesto, including Simone de Beauvoir’s sister Hélène, Catherine Deneuve, Marguerite Duras and Brigitte Fontaine, risked being taken to trial themselves for having an illegal abortion (abortion wouldn’t be made legal in France until the Veil law four years later). None of the women were called to trial and their manifesto helped draw the Bobigny trial to the public’s attention and lead to the acquittal and reduced sentences of the victims.

Agnès would later turn these events into a musical film, One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (L’une Chante, L’autre Pas), focusing on two women activists, brought together by their fight for abortion rights in France.

She lived in a pink house

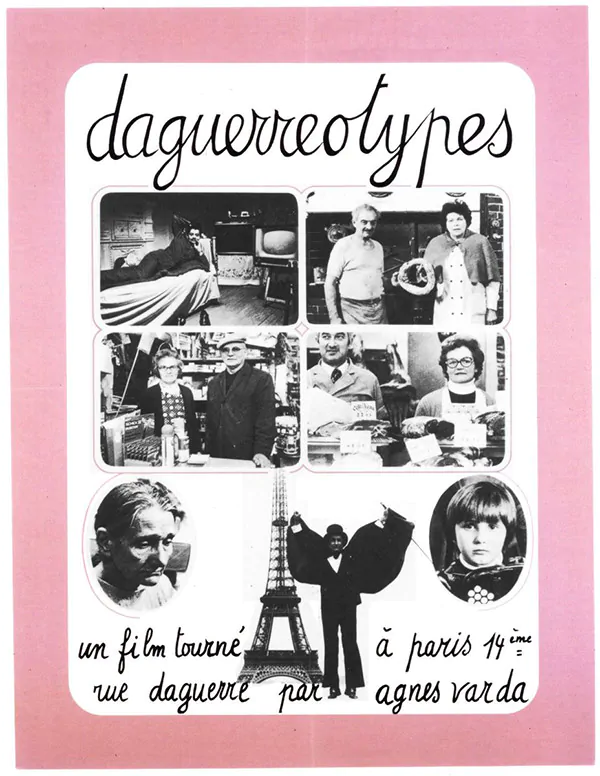

Varda didn’t live by conventions and that came down to where she chose to live too. From the 1950’s, Agnès had lived on Rue Daguerre in the 14th arrondissement of Paris with her husband Jacques Demy who she met in 1958. Agnès was a prominent figure in the neighbourhood, not only because she chose to paint her house pink with a rainbow over the garage door, but thanks to her daily interactions with the shopkeepers, market sellers and neighbours who made up her surrounding.

It was her own neighbourhood that became the inspiration for her 1976 film Daguerreotypes. In this tenderly made feature, it is her baker, butcher, tailor and perfumer who become the heroes of the narrative, their profiles building a picture of 1970s Paris and the world that Agnès lived in.

She made politics personal and didn’t shy away from difficult subjects

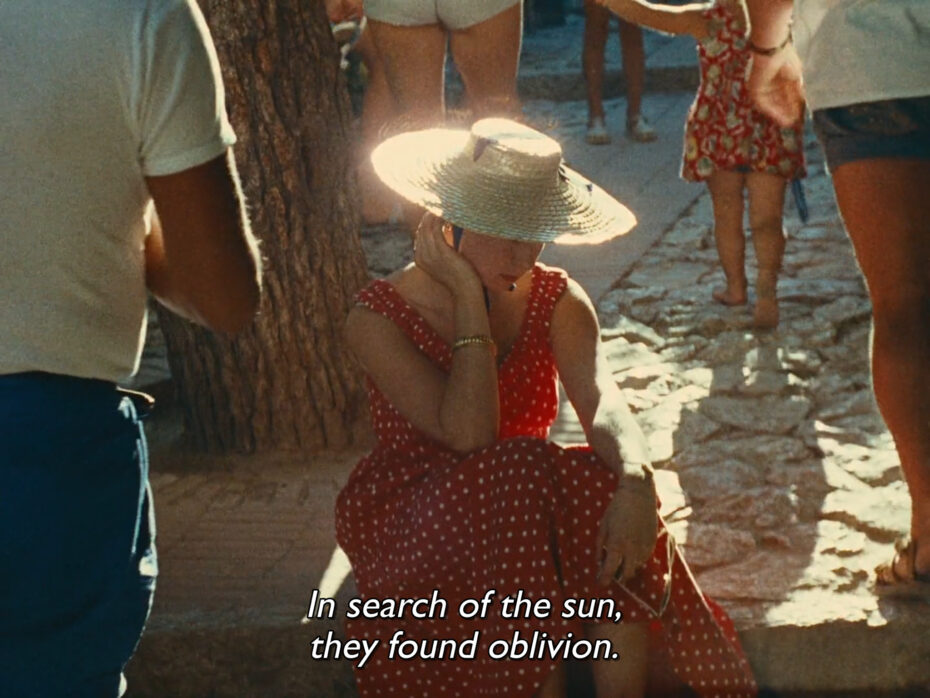

As well as shining a light onto the lives of ordinary people, Varda wasn’t afraid to tackle hard-hitting subjects. In 1963, she travelled to Cuba to interview Fidel Castro and in 1970, made the film Nausicaa, starring a young Gerard Depardieu about the military dictatorship of “the Colonels” in 1960s Greece, which she said was a “settling of accounts” with a “fascist” government.

Varda’s films at this point weren’t going unnoticed. Whilst living in America from 1968-1970, she met with members of the Black Panther party, who she featured in her documentary, Black Panthers. A documentary which would subsequently be censored in France after censors believed it could reawaken the explosive events of the May 68 student protests.

Agnès and her husband Demy separated for much of the 1980s, and shortly after they were reconciled, Demy was diagnosed with AIDS. As Demy grew sicker, he would stay inside their home, often writing down memories from his childhood. One day, Agnès came to him and suggested that they make a film of them. Demy would agree but with failing health, gave Agnès the rights to direct it. The film, Jacquot de Nantes, was shot on location in his hometown, in the garage that he had worked in as a boy. In the film we see extreme close ups of Jacques’ hair, skin and eyes, with Agnès saying later, “It was a way of filming to be near him”. Jacques died just 10 days after they finished filming in 1990 at the end of 59.

Fifteen years later, Varda would explore the loss of Jacques through her film Quelques Veuves de Noirmoutier (Some Widows of Noirmoutier, 2005). Here she interviews women on the island of Noirmoutier where she and Jacques shared a second home, about their experience of widowhood. She would later say, “Apart from their social status that inspires respect, we have not often studied how women live their widowhood. They are often— I would say almost always — defined by their relationship to the dead, who was their husband.”

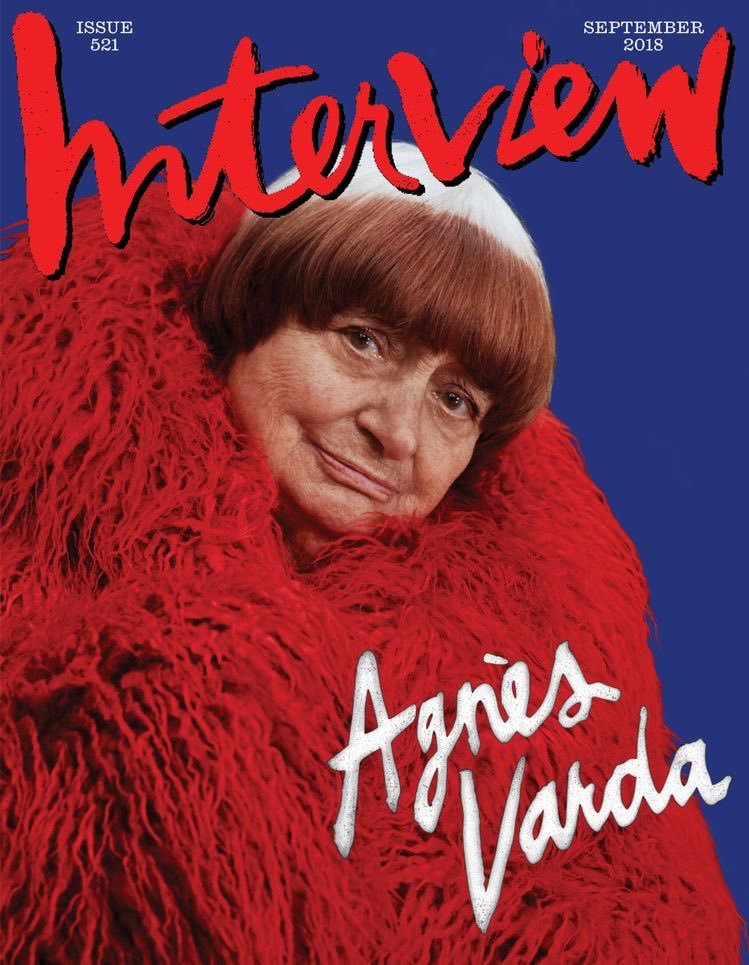

She found new fame in her late 80s

An unexpected setup by Agnès’ daughter Rosalie would suddenly find her experiencing a different kind of fame and celebrity, but one which ultimately celebrated her age. Rosalie introduced Varda to 35 year-old French artist JR. Establishing a deep connection early on, the two embarked on a new project Visages Villages (Faces Places) which saw them travel around the French countryside to photograph people they met along the way. The produced portraits on the road to be blown up and displayed prominently on buildings, shipping containers and even a barn. JR would say of his relationship with Agnès, “It was friendship at first sight”.

Faces Places went on to receive an Academy Award nomination for best documentary and suddenly Agnès was back in the spotlight. With her signature bowl cut hair at this point, silver at the crown and surrounded by burgundy, and a new appreciation for colourful two pieces, the media woke up and realised just what an artist she was, suddenly opening up galleries in Paris and Tokyo to her artwork once again.

American Vogue labelled her a fashion icon, she received an honorary Oscar for her lifetime film contributions and was recognised as an early pioneer for women’s right. Varda however was nonchalant about the new attention she received, preferring instead to turn her attention to the ordinary people who she had observed throughout her life and who had featured in so much of her work.

Whilst Agnès and JR didn’t win the Oscar in 2018, a year before, Agnès was the first female director to receive an honorary lifetime-achievement Oscar. She was also not only the oldest recipient of the Oscar at the time, but older than the ceremony itself.

On receiving the award, Agnès said, “It is a big event, very serious. But if I have to choose between serious and lightness, I choose lightness.” Varda then proceeded to grab the hand of Angelina Jolie who presented her with the award and began an impromptu dance to the jazz music playing in the ballroom.

Agnès would later say that she was “happy but not proud” of her Oscar, going on to say in an LA Times interview “…it’s like the academy is saying, That old lady has been working so continuously for cinema, at some point we should recognize that she worked. I feel like it’s recognition of my decent work. I made my first film, “La Pointe Courte,” in 1954, a radical film. How could somebody think that one day I would be recognized by the Hollywood world?” Agnès kept the Oscar in her kitchen, in a spot more likely reserved for a bowl of fruit.

People left potatoes instead of flowers outside her house after she died

Varda died on 28th March 2019 at the ago of 90, from complications related to breast cancer. In her lifetime, she built up more than fifty credits as a film director and over forty as a writer, an ability she called cinécriture, a portmanteau of cinéma and écriture (writing). Her work has spanned generations, political movements and social events. Outside her pink rainbow house, as people learnt of her passing, they left traditional flowers but also heart-shaped potatoes.

Agnès was affectionately known as dame patate or potato lady, a reference to a talk she made at the French Institute in New York in 2017, where she said she saw herself as a “heart-shaped potato – growing again” as she returned to working in film.

The potatoes reference also applied to Varda’s 2000 film “The Gleaners and I” which documented people around France who collect food and objects that others had left behind. Inspiration for the film struck Agnès whilst sat in a café in her beloved 14th arrondissement. Having not worked for a while she remarked on the men and women who arrived at the end of her local market, looking for the scraps left behind. This got Agnès thinking, “they are about to eat what we throw away” and this thought later became the Gleaners and I.

When asked if she believed in life after death Varda replied, “Oh, God, no. I’m part of nature. I’m delighted to become soil and dust.” Varda is now buried at the Montparnasse cemetery next to Demy, and to this day, people still bring heart-shaped potatoes to her grave and there was even calls for the street with her pink house to be renamed Rue Agnès Varda.

Varda lives on for her tenacity, her joie de vivre and her ability to see the ordinary and make it extraordinary. In a world that is often over photoshopped and over filtered, maybe we’d all be better off making like Agnès and celebrating the humble potato.

The complete collection of Agnès Varda’s films is available from Critireon Collection (which would make for a great gift to any film lover). Cleo from 5 to 7 is a great film to familiarise yourself with Varda’s earlier work and Vagabond (1985) has been called Agnès Varda’s Ulysses.

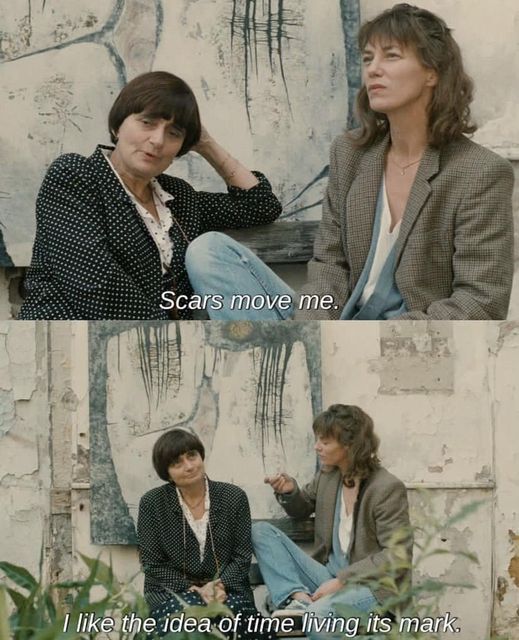

And because we’re equally and forever fans of the late Jane Birkin here at MNC, Varda’s biopic, Jane B par Agnès V.