The best way to make fast friends with a taxi driver in the Middle East? Ask them a simple question: “Fairuz or Umm Kulthum?” Sensational diva, singer, songwriter and actress, affectionately called ‘Egypt’s fourth pyramid’ and ‘mother of the Arabs’, Rolling Stones magazine ranked Umm Kulthum at number 61 of the 200 greatest singers of all time in 2023. But walk into most music stores west of the Mediterranean Sea asking for her records and the answer is more likely to be, ‘Umm, who?’ And what about Fairuz? Revered as the legendary “voice of Lebanon”, she’s the most celebrated living singer in the Middle East and one of the last singers from the golden age of Arabic music at 88 years old. Asking an Arab to choose between Fairuz and Umm Kulthum is a bit like asking an American to choose between Aretha Franklin and Nina Simone (or insert your own hard-to-choose-between artists here). Now, before we hop in that taxi, let’s get to know these divas of the East…

To young and old, rich and poor, no other artist is as beloved as Umm Kulthum (also written Oum Kalsoun) across the Arab world, from Palestine to Tunisia. She’s Egypt’s national treasure and most revered icon, praised by Bob Dylan and Maria Callas, who called her “the incomparable voice”, as well as Led Zeppelin’s lead singer Robert Plant, who said he was “driven to distraction” upon first hearing her, saying “when I first heard the way she would dance down through the scale to land on a beautiful note that I couldn’t even imagine singing it was huge: somebody had blown a hole in the wall of my understanding of vocals”. She has inspired innumerable artists to this day, 48 years after her death.

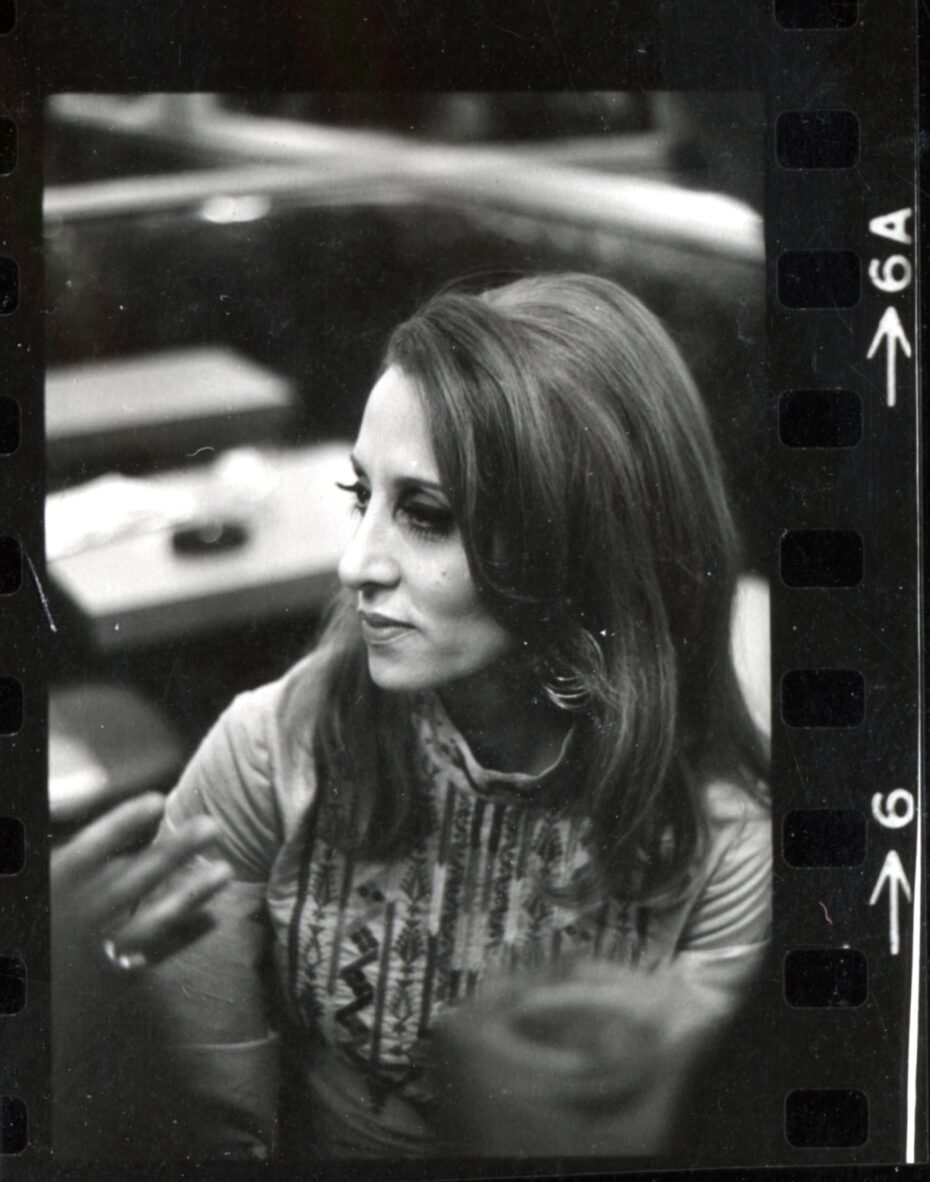

She came into this world in a small village called Tamay e-Zahayra in the Nile Delta on December 31st, 1898. As a toddler, she listened to her father, a countryside imam, teach her brother to sing, but soon it was clear that she was the real talent in the family. They were poor and her father struggled to keep his daughter in school, but the singing prodigy helped support the family by accompanying her father’s on his travelling acts to neighbouring regions. To keep adult men from looking at his daughter, he dressed her in boys’ clothes. At age 16, Mohamed Abo Al-Ela, who was a reasonably successful singer, spotted her and taught her some classical Arabic music, but it was a famous composer, Zakariyya Ahmad, who whisked her off to Cairo in the early 1920s. Odeon Records signed her up in 1923, and three years later she was earning more than any other Egyptian musician on the scene.

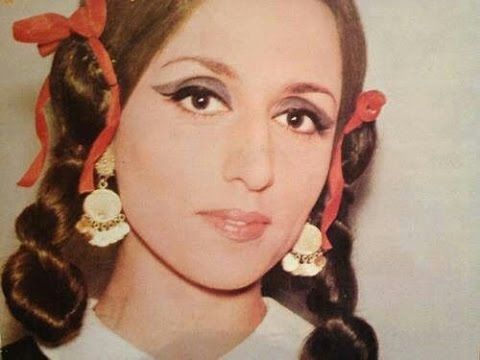

The journey of Fairuz (also written Fayrouz) towards musical stardom was equally humble. Born in Lebanon in 1935, her father, a talented oud player, instilled in her a deep appreciation for music and its cultural significance. In her early years, she sang in school plays and local events, honing her craft and gaining confidence in her mesmerizing voice. Her talent quickly became evident. At the age of 15, Nouhad was discovered by the Rahbani Brothers, Assi and Mansour, renowned composers and playwrights who recognized her vocal abilities. This encounter marked the beginning of a momentous collaboration that would shape the landscape of Arabic music. She didn’t just sing songs — she painted emotions with her voice, poignant lyrics and soul-stirring melodies.

By 1932, already well-established as an example to younger singers, Umm Kulthum set off on a tour to the Middle East and North Africa. She became a household name on Radio Cairo where she performed a concert every Thursday night for the next 40 years. The streets would literally empty every Thursday night with families gathering around the radio to hear their darling singer perform. A concert would last from 9.30 pm until the early morning hours of Friday. Her songs in the 1930s were typically focused on the age-old themes of love lost and found, and longing – in many ways quite similar to Western-style opera, a little like a dialogue (she sang solo) between her longer vocal passages and the retort of the orchestra.

Her voice was unparalleled: powerful, capable and clear, her songs virtuosic, romantic and modern. She relished the poetry written by the likes of Ahamad Rami and exquisitely interpreted his poems with her contralto voice (contralto singers are pretty rare and sing in the lowest keys of female voice). She had the uncommon ability to reach as low as the second octave and as high as the eighth octave. The strength of her voice (she could produce an incredible 14 000 vibrations per second) required her to step away at least three feet from her microphone. It was said that she wouldn’t sing a line the same way twice, and that every word she sang was crystal clear for everyone to understand first time around.

Every person in the Arab world could relate to her singing and her universally identifiable themes. Umm Kulthum’s performances could last up to five hours (during which, say, three songs would be sung) as the audience requested repetitions. She’d repeat the lines requested at length and spontaneously keep improvising in an ever-interactive exchange with her audience. Robert Plant of Led Zeppelin said, “I was intrigued by the scales, initially, and obviously the vocal work. The way she sang, the way she could hold a note, you could feel the tension, you could tell that everybody, the whole orchestra, would hold a note until she wanted to change.” In typical Middle Eastern singing tradition, she’d repeat a stance over and over, constantly reworking the emotive subtleties and intensity, systematically working up her audience into a euphoria known as tarab or ‘ecstacy’.

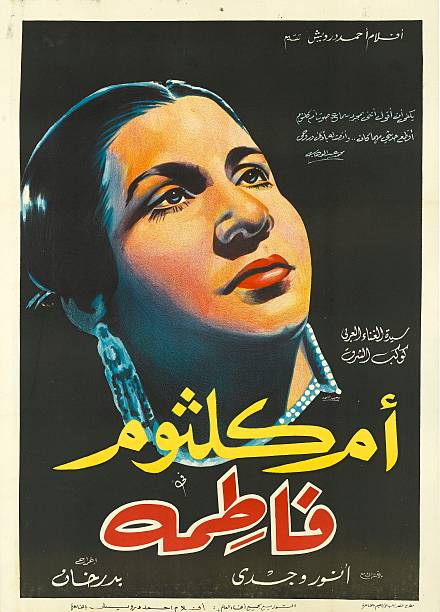

She penetrated the inner sanctum of every household and generations grew up with her constant presence and distinctive voice in what was a highly personalised relationship. Her talents also took her to the silver screen – she starred in Fritz Kramp’s film Weddad in 1936. Five other films followed, Sallima and Fatma perhaps the best-known ones.

Both Fairuz and Umm Kulthum hold an esteemed position as iconic figures, revered for their unparalleled contributions to music and their profound impact on audiences across generations and borders. Even Madonna and Beyoncé have been trying to capture some of their magic for their own sound. Beyoncé sampled Kulthum’s music on tour and in 1992, Madonna sampled Fairuz’s El Yawm Ulliqa Ala Khashab in her hit song Erotica, without obtaining permission. The musicians would settle matters outside of the court, but Madonna’s album and single were both banned in Lebanon.

Fairuz’s repertoire is a treasure trove of emotions, each song weaving narratives that speak to the shared experiences, joys, sorrows, and aspirations of the Arab world. Listening to Fairouz every morning is a tradition for many Arabs. For decades, almost all radio stations in the Arab world have been starting their morning broadcast with a Fairuz song. She is so popular in fact that if you google ‘Fairouz morning songs’ you will discover a plethora of beautiful songs or that are sure to please in the morning.

Her ability to infuse each lyric with raw emotion and sincerity became her signature, setting her apart as an artist. Her live performances were like spiritual gatherings, where people from all walks of life would come together, united by the power of music. Despite being a superstar, she remained down-to-earth, shying away from the glitz and glamour that often come with fame. Throughout her career, Fairuz’s songs became anthems for celebrations, revolutions, and moments of solace. Her voice became a symbol of resilience, hope, and cultural pride for the Arab world.

While Fairuz and Umm Kulthum share the status of being iconic figures in Arabic music, they represent different facets of the art form. Fairuz’s music tends to convey a more intimate, emotional connection, touching upon personal experiences and sentiments, while Umm Kulthum’s performances were grand, epic, and often associated with larger themes of patriotism and unity. Some might favor Fairuz’s soulful, delicate renditions that tug at heartstrings, while others might be drawn to the majestic, anthemic allure of Umm Kulthum’s powerful performances.

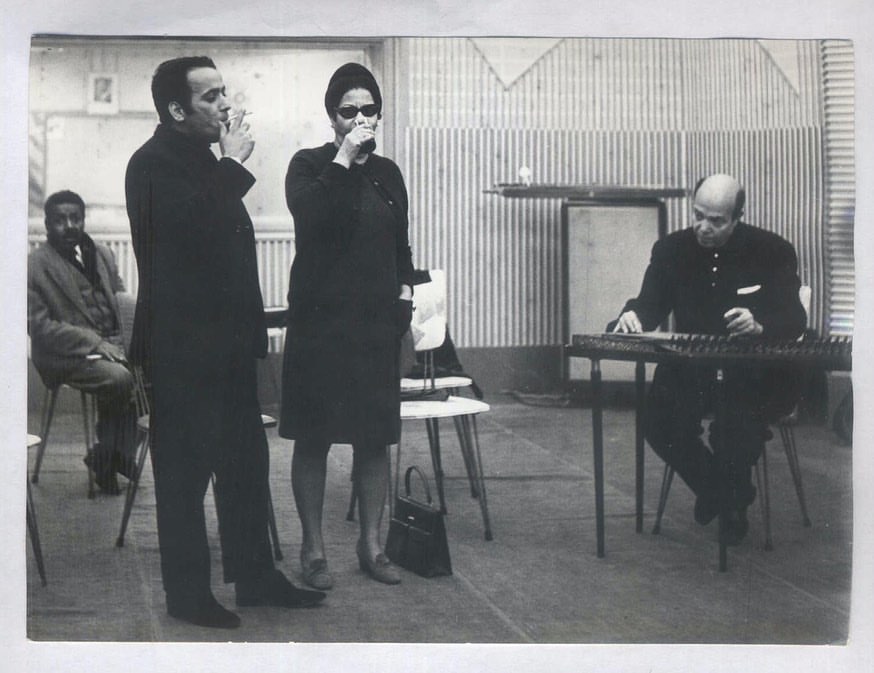

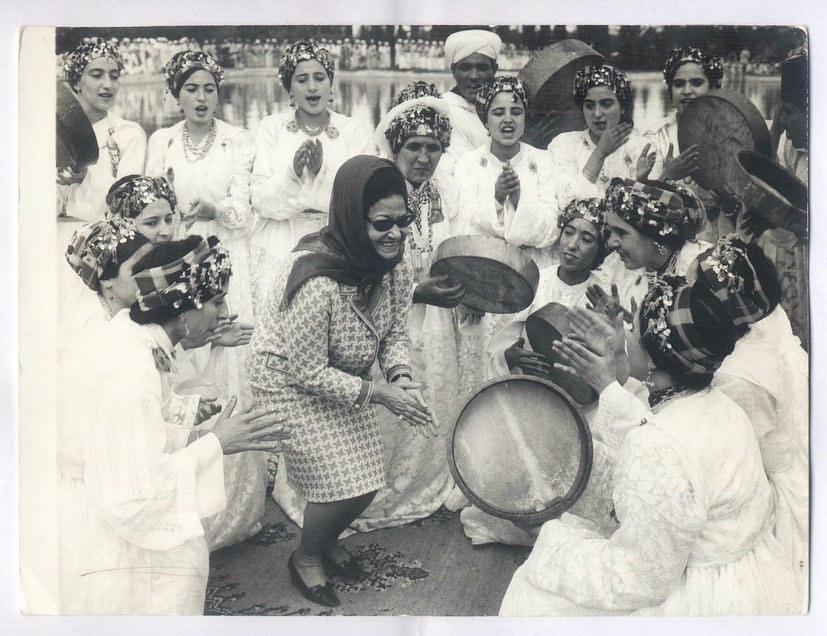

By 1966, Umm Kulthum’s voice had started to regress and she had started singing pieces that were western-influenced. In 1967, she paid a once-off visit to Paris and performed at L’Olympia; she received twice the amount of money Maria Callas received at the same venue. When Egypt was defeated and humiliated in the Six Day War in 1967, her songs took on a soul-searching and even more poignant tone. Allegedly Umm Kulthum isolated herself to the basement of her house and took the defeat extremely personally. She went on to give innumerable concerts thereafter, donating the proceeds to the government to rebuild bricks and mortar as well as morale.

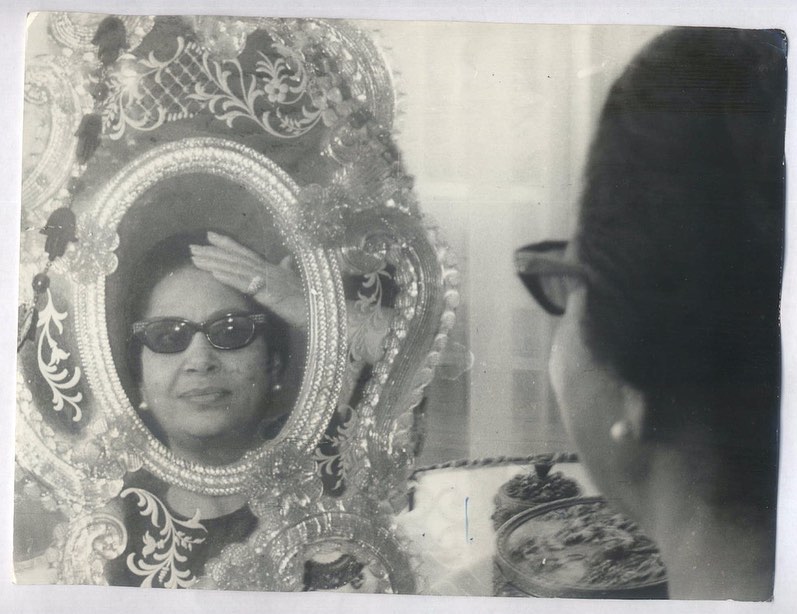

Umm Kulthum died of heart failure while performing in 1975, at age 76. Four million people lined the streets, a greater audience than President Abdel Nasser commanded. She was buried in the City of the Dead in Cairo, not far from the Nile. The news of her death made headlines across the far corners of the globe. In 2001, the Egyptian government established the Kawkab al-Sharq Museum in her memory on the grounds of Cairo’s Manesterly Palace, with a collection that includes her signature scarves, sunglasses, personal items, photographs and recordings. A monument was erected in her honour in Zamalek, Cairo, on the site of her former house. Walk around in Baghdad and you’ll encounter many cafés, faithfully keeping her memory alive. The Louvre in Abu Dhabi still exhibits her signature pearl necklace with its 1888 pearls. Forty-eight years after her death, at 10pm on the first Thursday of every month Egyptian radio stations still dedicate a program to her music.

Despite her unparalleled fame and adoration, Fairuz remains an intensely private figure, shunning the spotlight and preferring to let her music speak volumes on her behalf. Her songs continue to be cherished by new generations; fans old and new, who find solace, nostalgia, and inspiration in her timeless melodies.

Both revered as symbols of Pan-Arab aspiration, unity, nationalism, freedom, pride and hope. Her raw talent and determination kept her in the limelight for decades while she was alive, and it seems for decades thereafter. Whether one finds yourself in Beirut or Cairo, wafting across from a town square or a rooftop restaurant or the open window of a taxi, those inimitable sensuous sounds of Egypt’s eternal star with her signature scarf in hand, or Lebanon’s enduring celestial voice, may just come and find you.