We all know Toulouse-Lautrec, but how about Georges Bottini? You won’t find a single plaque or street name commemorating his memory, but if there were any artist eponymous with life in bohemian Montmartre, it’s him. He was a true creature of the Montmartre underworld, an artist whose colourful and expressive snapshots inspired Picasso. So scoot over Toulouse-Lautrec; let’s delve into the weird and wonderful story about one of Montmartre’s native “Painter of bars and girls.”

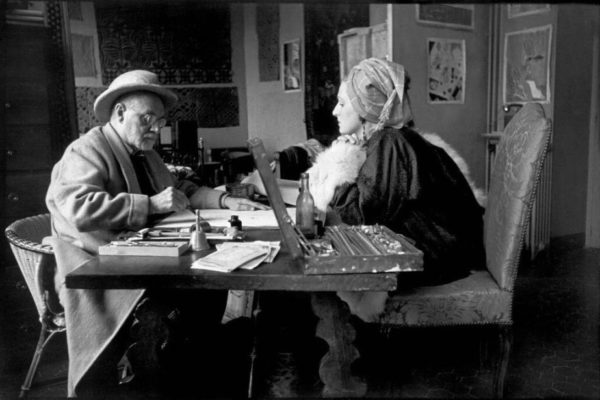

Unlike Toulous-Lautrec, George Bottini came from humble origins, being the son of a Parisian hairdresser and a laundress. After his family could no longer cover his school fees, he left his education to work, job-hopping from one trade to another until he discovered a love for art. Bottini did not go to any fancy art academy, though; he rather spent time in museums like the Louvre, where he learned to draw and paint by learning from the masters. He eventually went to train in Fernand Cormon’s atelier libre (open studio) on the ground floor of 104 Boulevard de Clichy – the same studio that also took Vincent Van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec under its wing.

Bottini left home, renting a cramped room on the rue d’Amsterdam, where he bunked up with future writer and critic Gaston de Pawlowski, who’d become famous for his science fiction novel Voyage to the Land of the Fourth Dimension. The duo often frequented Montmartre’s bars, cabarets, and bohemian underworld with painter and caricaturist Fabien Launay in tow. They were regulars at the Auberge du Clou, an artistic and literary sanctuary that allowed broke artists to loiter and hang their art there while waiting to pay their bills, and its adjoining cabaret l’Âne Rouge, a famous hangout for irreverent painters, authors, and singers.

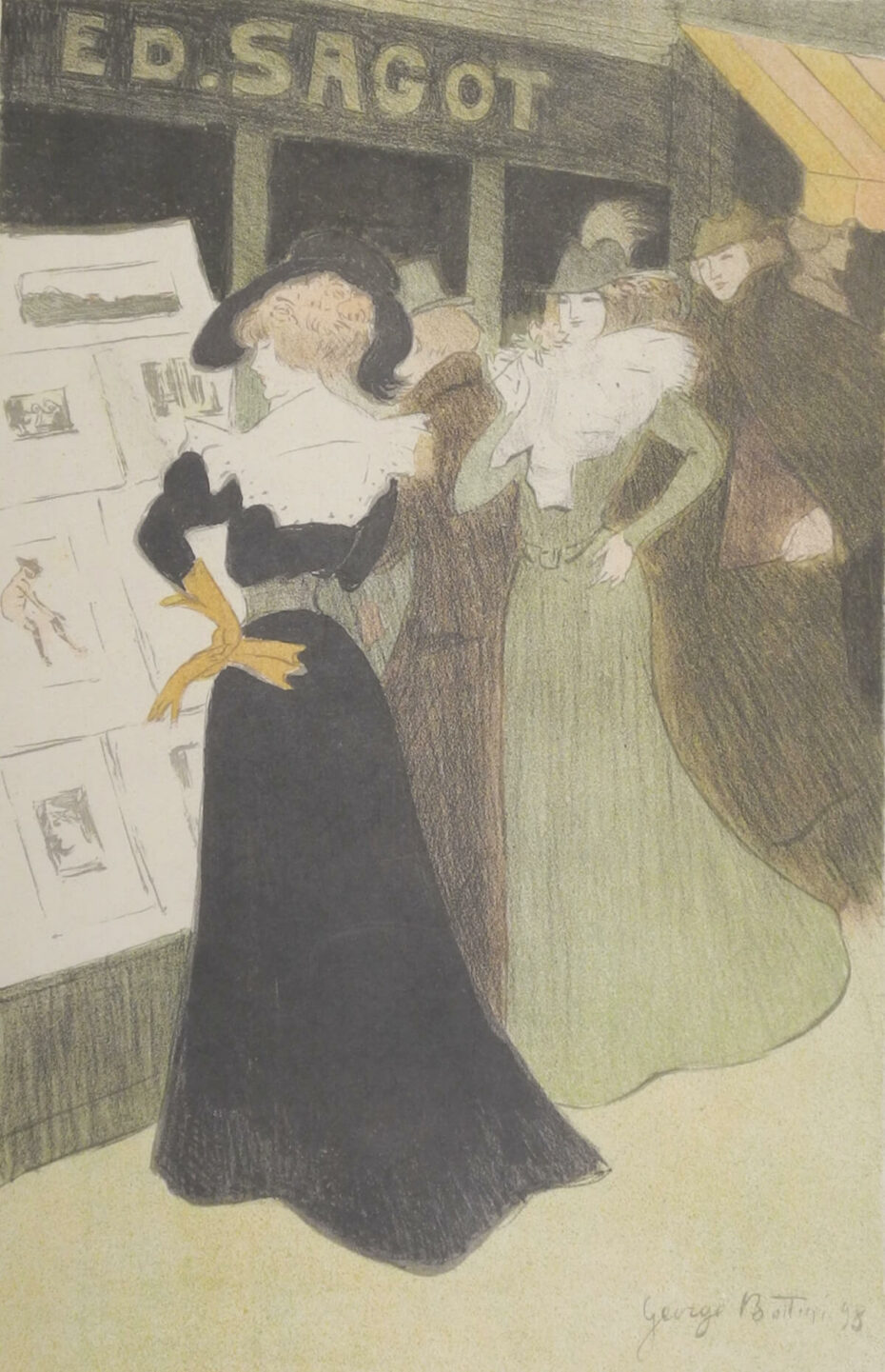

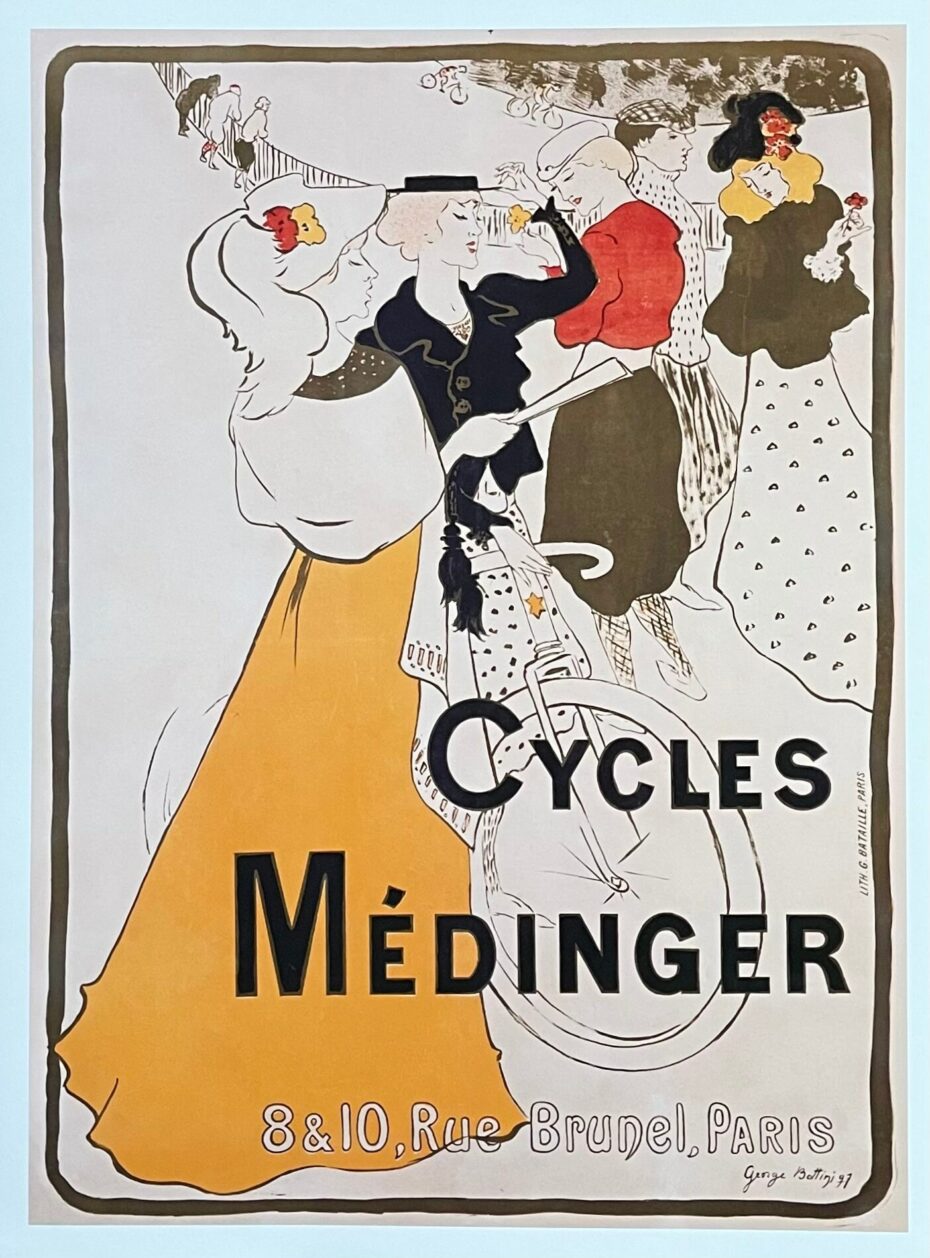

Things became exciting for Bottini at the turn of the century, who found himself at the throngs of bohemian life as a developing artist. In Cormon’s atelier libre, he befriended Louis Anquetin, an artist who was one of the core founders of the Cloisonnism art movement (also known as Partitionism), which was inspired by stained glass and Japanese ukiyo-e art. It was Anquetin who introduced him to Japanese prints that would influence Bottini’s art. And it’s no coincidence that Lautrec also found inspiration in Japanese art, as he also befriended Anquetin. Bottini was versatile and didn’t tie himself to any one movement or manifesto. He designed fashion, posters, urban landscapes, cabaret scenes, and interior sketches, and his work was sometimes approached with attentiveness and tenderness, other times with a more critical or even ironical gaze.

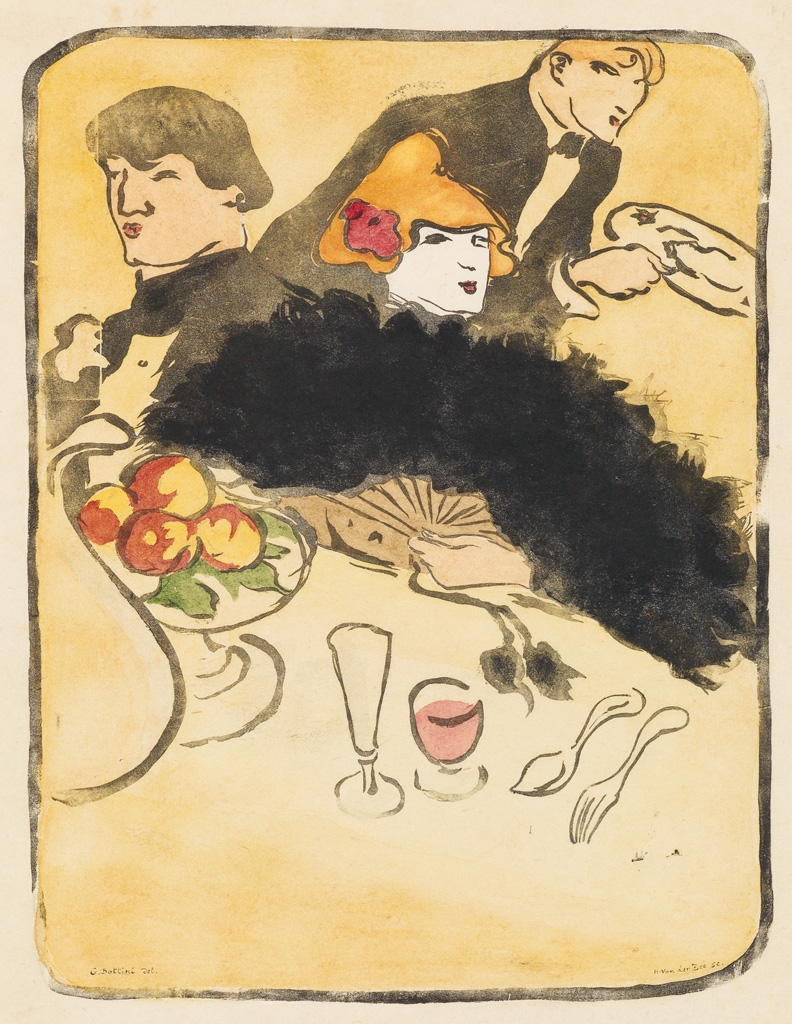

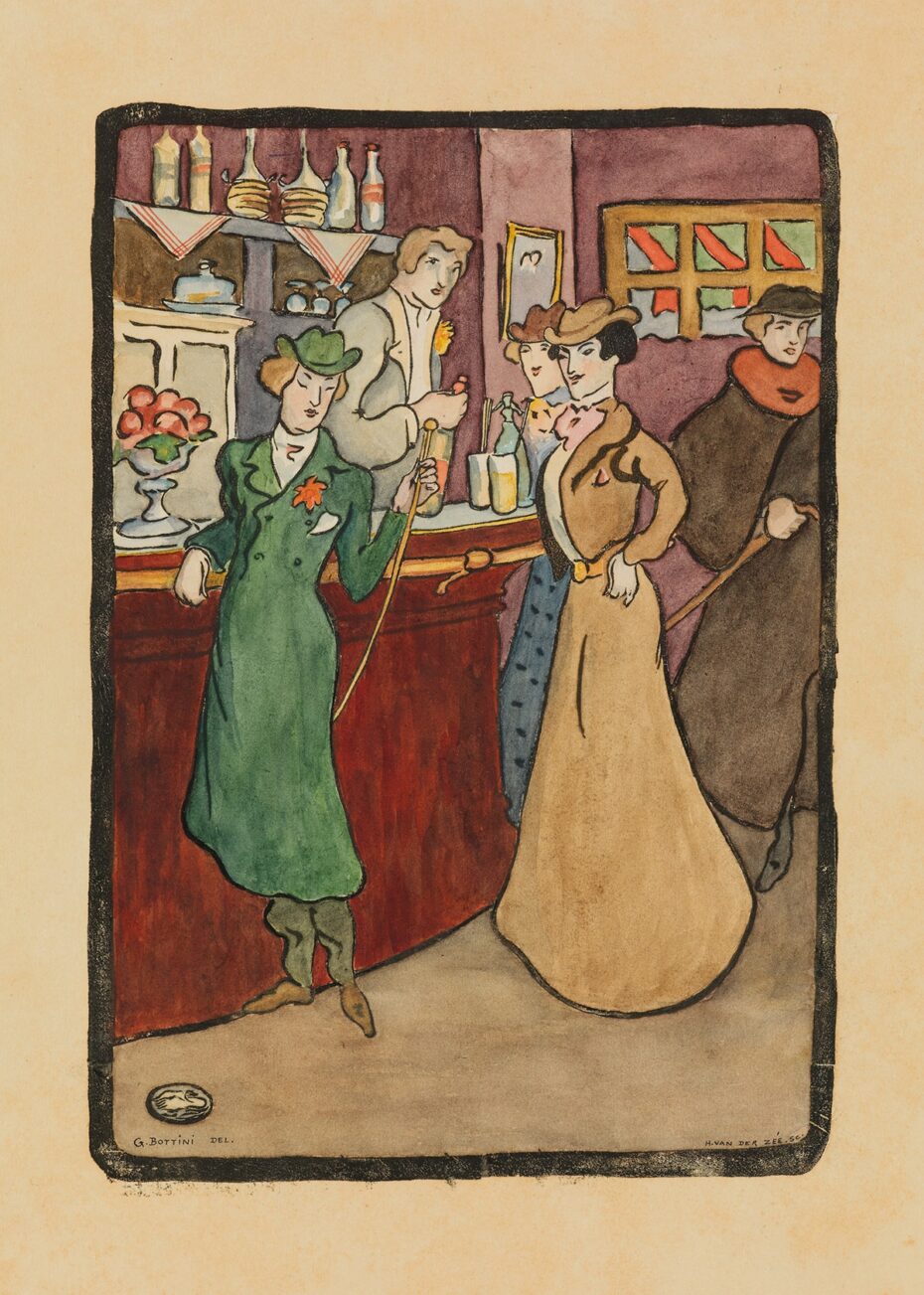

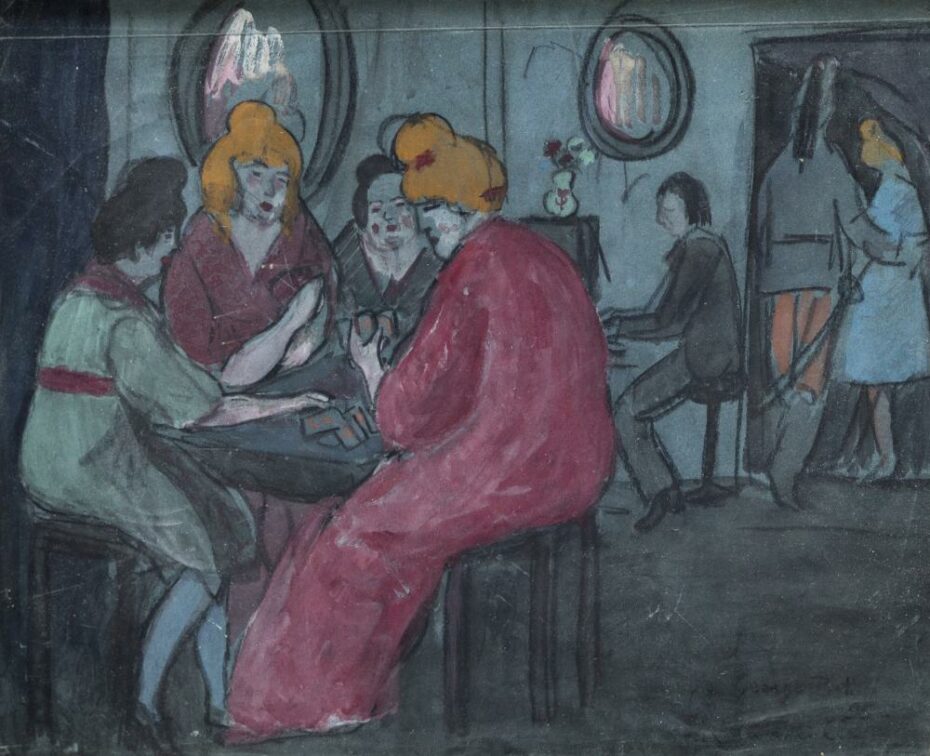

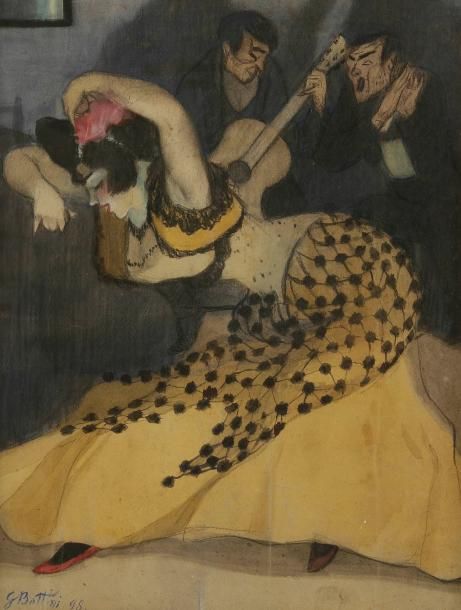

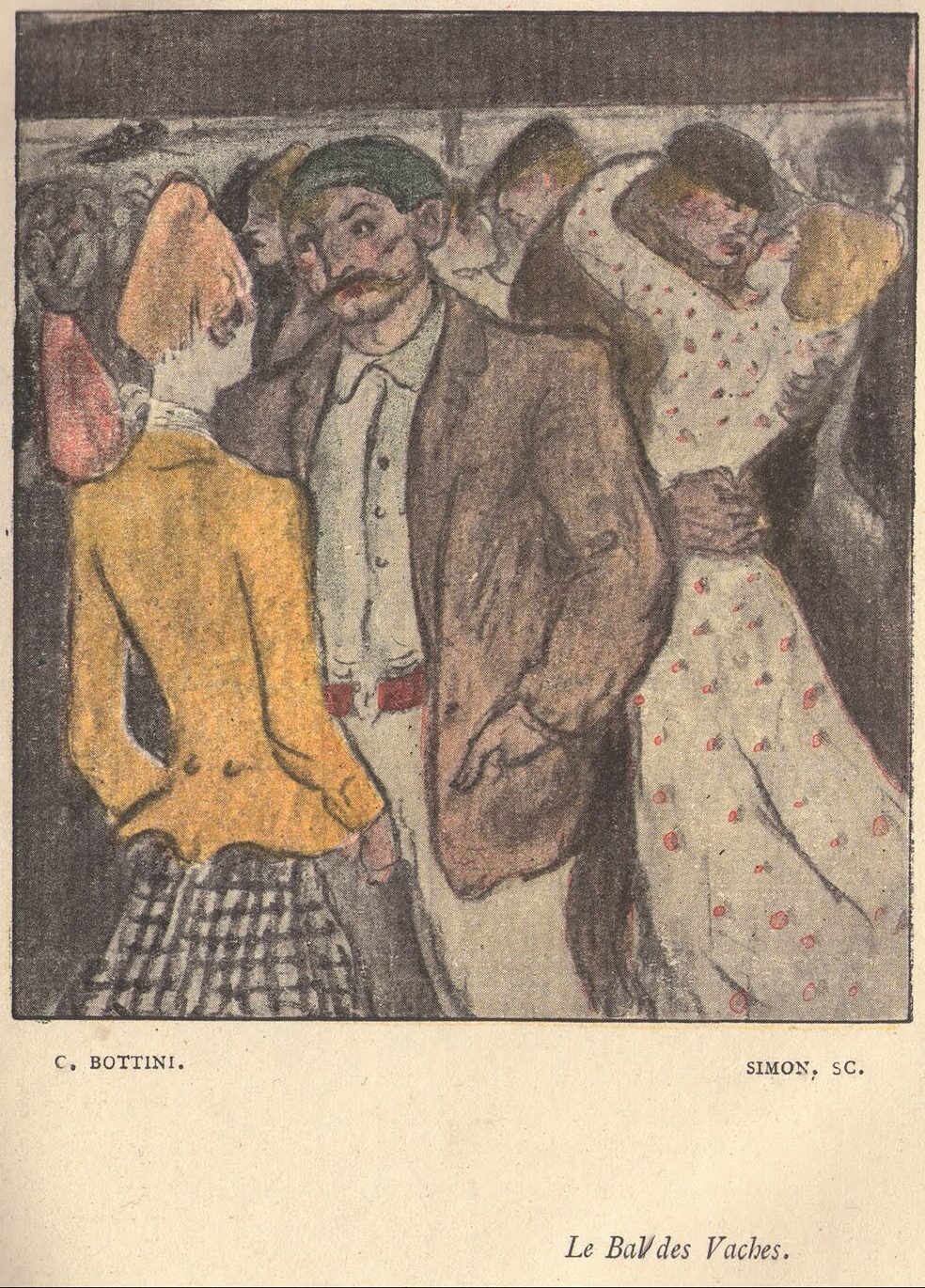

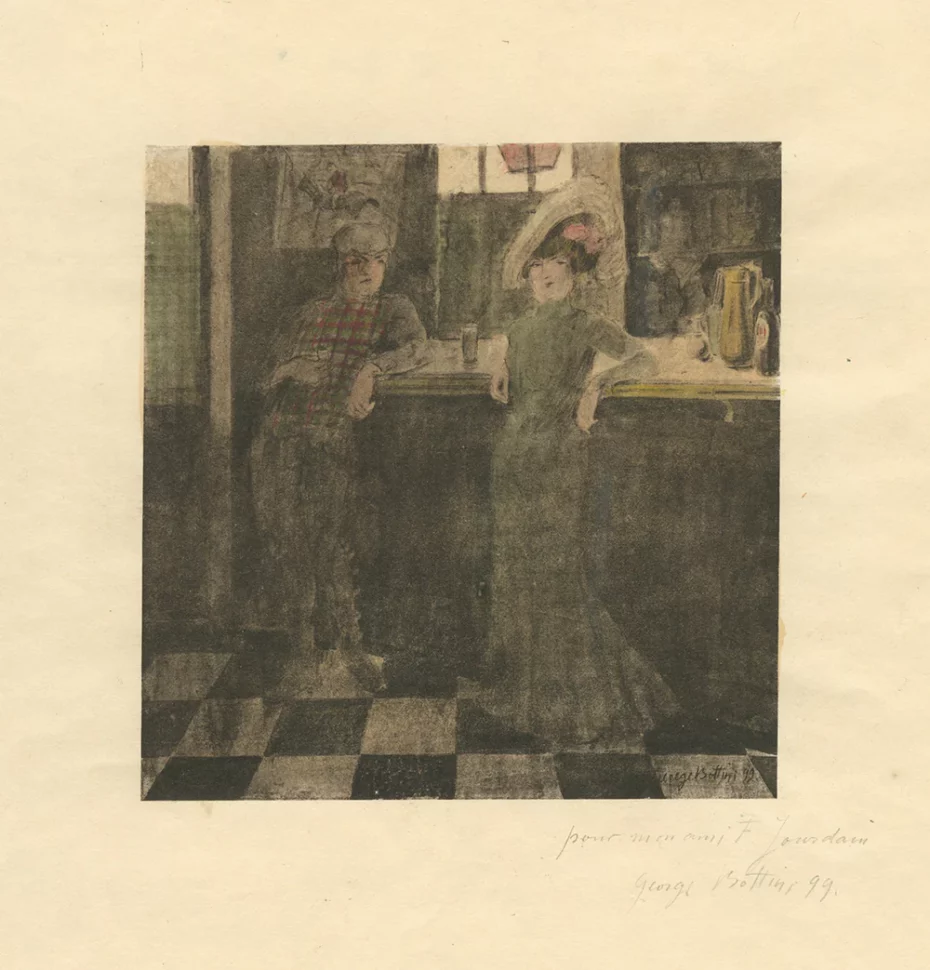

Bottini also took to the surroundings he loved best – the nighttime haunts of Montmartre – and documented them, drawing inspiration from Constantin Guys and his contemporaries like Toulouse-Lautrec. By day, he’d paint landscapes depicting Montmartre’s life, and by night, he’d turn to his muses; prostitutes and other creatures of the night who frequented the cabarets of Montmartre after sunset. With Toulouse-Lautrec, he spent many nights furiously sketching in the Moulin de la Galette, the Bal Tabarin, the bars of Avenue Traudaine, and in brothels in the area until the early hours, while the absinthe dripped through the sugar cubes set on punctured spoons.

When he exhibited his work for the first time in 1899, Gustave Geffroy hailed him as a master, and author Jean Lorrain lauded the artist for his “sooty atmosphere” and “innate elegance” of the demi-mondaine milieu. The artist exhibited in prestigious events like exhibitions at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and the Paris Salon between 1897 and 1906. Some might even say he was on the trajectory of becoming one of the great painters of his generation.

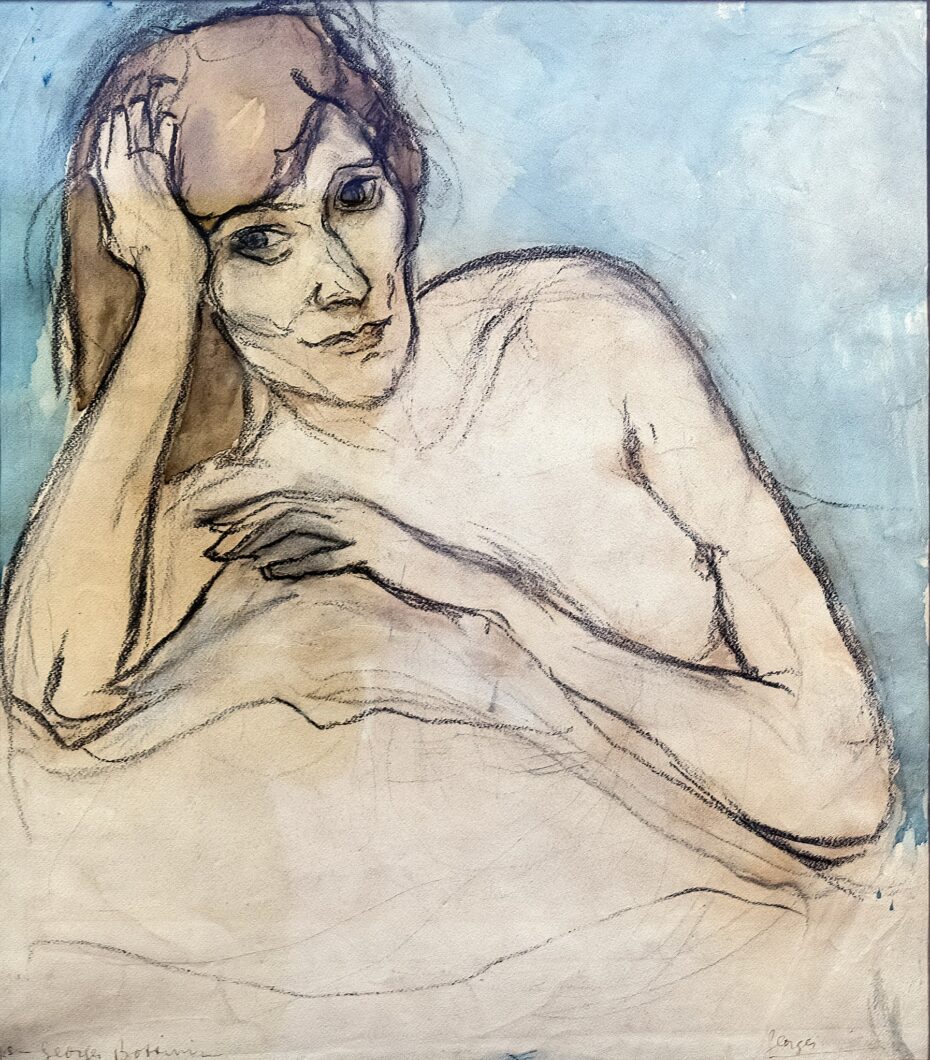

He even impressed Picasso when they met in a café (or, more likely, a brothel) in Pigalle. His paintings were bright and colourful, but sadly, it seems his work enjoyed little commercial success. Sometimes, the controversial nature of his paintings, featuring prostitutes and queer women were too risqué for certain salons, like at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, which would hang his work close to the ceiling or away from the light so it couldn’t be seen easily. What is curious about his art, though, particularly in his depictions of same-sex relationships between women as something natural and carefree, Bottini avoided depicting them in demeaning positions, typical of the male gaze at the time that most artists used when painting the same subject matter.

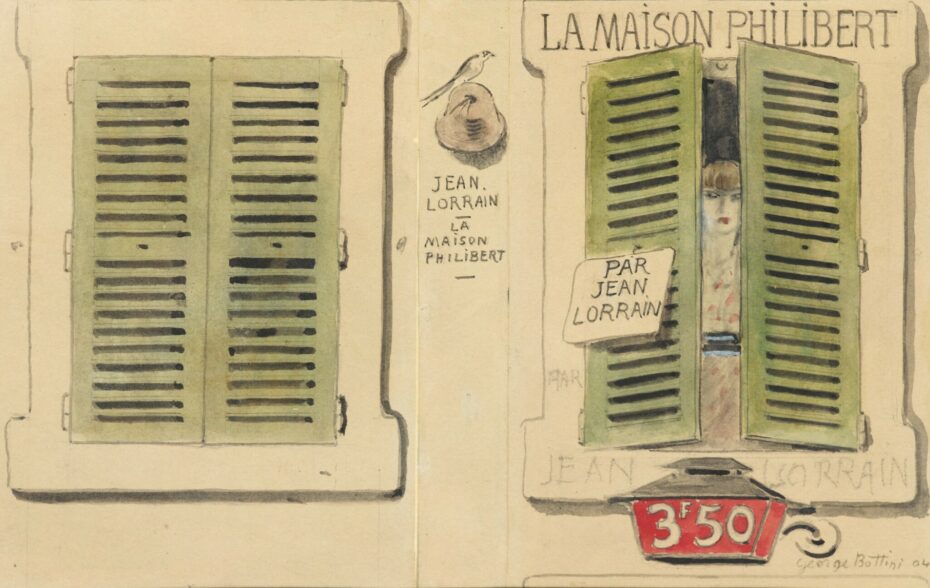

However, those with a taste for Bottini’s clandestine subject matters would seek his collaboration. Jean Lorrain approached Bottini to illustrate his novel, “La Maison Philibert,” set in a brothel where different worlds and vices mingled, knowing that Bottini was an artist who knew that world intimately. Bottini was consumed by the subject, perhaps even haunted by it, but the artistic community around him admired his skill, even if the general public were too conservative to appreciate his work. Critic Arsène Alexandre called him “The Goya of Montmartre, the Guys of our time.” He earned a solid reputation as an illustrator, not only illustrating Jean Lorrain’s book “La Maison Philibert,” he’d go on to work on books by Gustave Coquiot and Félicien Champsaur.

Yet, one day, his intense bohemian lifestyle would catch up with him. He endured sleepless night after sleepless night, accompanied by his friends and the liberal lashings of the Green Fairy. His absinthe-laden nights of pure hedonism in the clubs and brothels of Montmartre continued untill he began to lash out in irrational and violent episodes. As Bottini’s mental health deteriorated, he grew increasingly violent and suffered serious, devastating attacks. Some believe he caught syphilis, while others thought it was due to his excessive absinthe consumption, a condition referred to as “absinthism.” He was bound in a straitjacket and taken to Villejuif Asylum after he attacked and almost killed his mother in a violent rage. In 1907, while in confinement, Bottini died at the young age of 33.

Bottini was certainly an artist of his time, capturing the wild, nocturnal underworld of Belle Epoque Paris. He embodied the bohemian spirit of Montmartre, painting the world around him with frankness and a unique expression that drew inspiration from the old masters, his peers, and Japanese art.

He was an observer, and while his life was short-lived and tragic, he created art that captured the spirit of his world. Sadly, unlike his contemporary Toulouse-Lautrec, even though he was an esteemed painter, draughtsman, lithographer, poster artist, and book illustrator, he seems to have disappeared from the annals of history.